Money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context.[1][2][3] The primary functions which distinguish money are as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value and sometimes, a standard of deferred payment.

Money historically possessed intrinsic value as a commodity such as grain, gold, or silver. Nearly all contemporary money systems are based on unbacked fiat money without use value.[4] Its value is consequently derived by social convention, often declared by a government or regulatory entity to be legal tender; that is, it must be accepted as a form of payment within the boundaries of the country, for "all debts, public and private," in the case of the United States dollar.

The money supply of a country comprises all currency in circulation (banknotes and coins currently issued) and, depending on the particular definition used, one or more types of bank money (the balances held in checking accounts, savings accounts, and other types of bank accounts). Bank money, whose value exists on the books of financial institutions and can be converted into physical notes or used for cashless payment, is the largest part of broad money in developed countries.

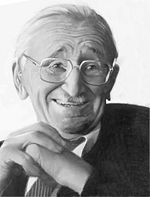

Because it has value, money has been a target of theft and fraud. Governments and powerful economic institutions have sought to regulate and control money. The corrupt use of public money has been rampant. Friedrich von Hayek argued that money is one of three spontaneous social institutions,[5] and that governments continually interfere with its natural development.

History

The use of barter-like methods may date back to the first human societies,[6] Non-currency societies may have operated largely along the principles of gift economy and debt.[7][8] Barter without stand money was necessary between complete strangers.[9]

Many cultures worldwide eventually developed the use of commodity money. The Mesopotamian shekel was a unit of weight and relied on the mass of something like 160 grains of barley.[10] The first usage of the term came from Mesopotamia circa 3000 B.C.E., where the was wide civilizational travel and anonymous transactions. Some early societies in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia used shell money. According to Herodotus, the Lydians were the first people to introduce the use of gold and silver coins.[11] It is thought by modern scholars that these first stamped coins were minted around 650 to 600 B.C.E.[12]

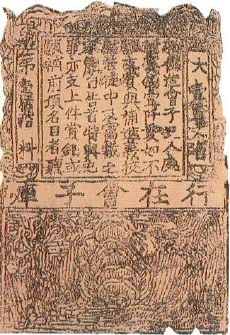

The system of commodity money eventually spun off systems of representative money, i.e. promissory notes that were traded because gold and silver merchants or banks made them redeemable for the commodity money deposited. Paper money or banknotes were first used in China during the Song dynasty. These banknotes, known as "jiaozi," evolved from promissory notes that had been used since the 7th century. However, they did not displace commodity money and were used alongside coins. In the 13th century, paper money became known in Europe through the accounts of travelers, such as Marco Polo and William of Rubruck.[13] Marco Polo's account of paper money during the Yuan dynasty is the subject of a chapter of his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, titled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made Into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All Over his Country."[14]

In 1609 the Bank of Amsterdam was created as an exchange bank, an early central bank. The small country was awash in coins and currencies from various issuers. The Bank of Amsterdam brokered the exchange of money and guaranteed the settlements in an accounting unit called the florin. The florin was the first instance of what is called stablecoin, a term developed to describe cryptocurrencies whose value is pegged to some outside reference to maintain price stability for commercial transactions. The bank formed a single economic function that escaped many government conflicts of interest.[15] Due to its sound financial practices, the Bank of Amsterdam’s currency became a reserve currency, the dominant currency in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries.[16]

The gold standard, a monetary system where the medium of exchange is paper notes that are convertible into preset, fixed quantities of gold, replaced the use of gold coins as currency in the 17th–19th centuries in Europe. These gold standard notes were made legal tender. With the impending failure of the Bank of England in 1686, the redemption of gold coins was suspended and then later discouraged by the government, which needed the bank to have reserves for loans to spread the Empire. At the beginning of the 20th century, almost all countries had adopted the gold standard, backing their legal tender notes with fixed amounts of gold.

After World War II and the Bretton Woods Conference, most countries adopted fiat currencies that were fixed to the U.S. dollar. At the war's end, the U.S. had the largest amount of gold reserves, and the dollar became the world reserve currency. In 1971 the U.S. government suspended the convertibility of the dollar to gold, and many countries de-pegged their currencies from the U.S. dollar. The dollar remained the world reserve currency as most oil was traded in dollars, often termed "petro-dollars." Today most of the world's currencies are declared official by government laws that make it mandatory for merchants to accept payment in the national currency. In the West, fiat money is also backed by taxes. By imposing taxes, states create demand for the currency they issue.[17] In the United States, the Sixteenth Amendment was required to allow direct taxation of citizen's to enable the Federal Reserve System to print money for the government against tax debt. The European Central Bank, which also serves many sovereign states, was developed on that model.

Functions

In Money and the Mechanism of Exchange (1875), William Stanley Jevons famously analyzed money in terms of four functions: a medium of exchange, a common measure of value (or unit of account), a standard of value (or standard of deferred payment), and a store of value. By 1919, Jevons's four functions of money were summarized in the couplet:

- Money's a matter of functions four,

- A Medium, a Measure, a Standard, a Store.[18]

This couplet would later become widely popular in macroeconomics textbooks.[19] Most modern textbooks now list only three functions, that of medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value, not considering a standard of deferred payment as a distinguished function, but rather subsuming it in the others.[4][20][21]

There have been many historical disputes regarding the combination of money's functions, some arguing that they need more separation and that a single institution is insufficient to deal with them all. One of these arguments is that the role of money as a medium of exchange conflicts with its role as a store of value: its role as a store of value requires holding it without spending, whereas its role as a medium of exchange requires it to circulate.[22] Others argue that the storing of value is just a deferral of the exchange, but this does not diminish the fact that money is a medium of exchange that can be transported both across space and time. The term "financial capital" is a more general and inclusive term for all liquid instruments, whether or not they are uniformly recognized tender.

Medium of exchange

When money is used to intermediate the exchange of goods and services, it is performing a function as a medium of exchange. It thereby avoids the inefficiencies of a barter system, such as the inability to permanently ensure "coincidence of wants". For example, between two parties in a barter system, one party may not have or make the item that the other wants, indicating the non-existence of the coincidence of wants. Having a medium of exchange can alleviate this issue because the former can have the freedom to spend time on other items, instead of being burdened to only serve the needs of the latter. Meanwhile, the latter can use the medium of exchange to seek for a party that can provide them with the item they want.

Measure of value

A unit of account (in economics)[23] is a standard numerical monetary unit of measurement of the market value of goods, services, and other transactions. Also known as a "measure" or "standard" of relative worth and deferred payment, a unit of account is a necessary prerequisite for the formulation of commercial agreements that involve debt.

Money acts as a standard measure and a common denomination of trade. It is thus a basis for quoting and bargaining of prices. It is necessary for developing efficient accounting systems like double-entry bookkeeping.

Standard of deferred payment

While standard of deferred payment is distinguished by some texts,[22] particularly older ones, other texts subsume this under other functions. A "standard of deferred payment" is an accepted way to settle a debt—a unit in which debts are denominated, and the status of money as legal tender, which may be used the discharge of debts. When debts are denominated in money, the real value of debts may change due to inflation and deflation, and for sovereign and international debts via debasement and devaluation.

Store of value

Originally banks were storehouses to keep quantities of people's money safe for a fee. To act as a store of value, money must be reliably saved, stored, and retrieved—and be predictably usable as a medium of exchange when it is retrieved. The value of the money must also remain stable over time. Some have argued that inflation, by reducing the value of printed money, diminishes the ability to use it as a store of value. In that case, gold and precious metals function better.

Properties

The functions of money are that it is a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value.[24] To fulfill these various functions, money must be:[25]

- Fungible: its individual units must be capable of mutual substitution (i.e., interchangeability).

- Durable: able to withstand repeated use.

- Divisible: divisible to small units.

- Portable: easily carried and transported.

- Acceptable: most people must accept the money as payment

- Scarce: its supply in circulation must be limited.

- Anonymous: It must pass reliably without any restriction because of the previous holder.

Money supply

In economics, money is any financial instrument that can fulfill the functions of money (detailed above). These financial instruments together are collectively referred to as the money supply of an economy. Since the money supply consists of various financial instruments (usually currency, demand deposits, and various other types of deposits), the amount of money in an economy is measured by adding together these financial instruments creating a monetary aggregate.

Economists employ different ways to measure the stock of money or money supply, reflected in different types of monetary aggregates, using a categorization system that focuses on the liquidity of the financial instrument used as money. The most commonly used monetary aggregates (or types of money) are conventionally designated M1, M2, and M3. These are successively larger aggregate categories: M1 is currency (coins and bills) plus demand deposits (such as checking accounts); M2 is M1 plus some savings accounts and time deposits under $100,000; M3 is M2 plus larger time deposits and similar institutional accounts. M1 includes only the most liquid financial instruments, and M3 includes relatively illiquid instruments. The precise definition of M1, M2, etc. may differ by country.

Another measure of money, M0, is also used. M0 is base money, or the amount of money actually issued by the central bank of a country. It is measured as currency plus deposits of banks and other institutions at the central bank. M0 is the only money that can satisfy the reserve requirements of commercial banks.

Creation of money

In current economic systems, money is created by two procedures:

Legal tender, or narrow money (M0), is the currency created by a Central Bank by minting coins and printing banknotes.

Bank money, or broad money (M1/M2), is the money created by private banks by recording loans as deposits of borrowing clients using fractional reserve banking. Currently, bank money is mostly created as electronic money.

Bank money, whose value exists on the books of financial institutions and can be converted into physical notes or used for cashless payment, forms by far the largest part of broad money in developed countries.[26][27][28] In most countries, most M1/M2 money is created by commercial banks making loans.

Market liquidity

"Market liquidity" describes how easily an item can be traded for another item, or into the common currency within an economy. Money is the most liquid asset because it is universally recognized and accepted as a common currency. In this way, money gives consumers the freedom to trade goods and services easily without having to barter.

Liquid financial instruments are easily tradable and have low transaction costs. There should be no (or minimal) spread between the prices to buy and sell the instrument being used as money.

Types of Money

Commodity

Many items have been used as commodity money such as naturally scarce precious metals, shells, barley, beads, etc., as well as many other things that are thought of as having value. Commodity money value comes from the commodity out of which it is made. The commodity itself constitutes the money, and the money is the commodity.[29] Examples of commodities that have been used as mediums of exchange include gold, silver, copper, rice, Wampum, salt, peppercorns, large stones, grain, shells, pelts, alcohol, cigarettes, etc. These items were sometimes used as a metric of perceived value in conjunction with one another in various commodity valuations or price system economies. The use of commodity money is like barter, but commodity money represents a unit of account. Although some gold coins such as the Krugerrand are considered legal tender, there is no record of their face value on either side of the coin. The rationale is that emphasis is laid on their direct link to the prevailing value of their fine gold content. American Eagles are imprinted with their gold content and legal tender face value.

Representative

In 1875, the British economist William Stanley Jevons described the money used at the time as "representative money". Representative money is money that consists of token coins, paper money or other physical tokens such as certificates and notes that can be reliably exchanged for a fixed quantity of a commodity like gold or silver. While not having intrinsic value, representative money can be converted to commodities that have intrinsic value.[30]

Fiat

Fiat money or currency has no intrinsic value or guarantees that it can be converted into a valuable commodity (such as gold). Instead, it has value only by government order (fiat). Usually, the government declares the fiat currency (typically notes and coins from a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve System in the U.S.) to be legal tender, making it unlawful not to accept the fiat currency as a means of repayment for all debts, public and private.[31][32] Some bullion coins such as the Australian Gold Nugget and American Eagle are legal tender. However, they trade based on the market price of the metal content as a commodity rather than their legal tender face value (which is usually only a small fraction of their bullion value).[33][34]

Fiat money, if physically represented as currency (paper or coins), can be accidentally damaged or destroyed. However, fiat money has an advantage over representative or commodity money because the same laws that created the money can also define rules for its replacement in case of damage or destruction. For example, the U.S. government will replace mutilated Federal Reserve Notes (U.S. fiat money) if at least half of the physical note can be reconstructed or if it can be otherwise proven to have been destroyed.[35] By contrast, commodity money that has been lost or destroyed cannot be recovered.

Coins

These factors led to the shift of the store of value being the metal itself: at first silver, then both silver and gold, and at one point, bronze. Now we have copper coins and other non-precious metals as coins. Metals were mined, weighed, and stamped into coins. This was to assure the individual taking the coin that he was getting a certain known weight of precious metal. Coins could be counterfeited, but they also created a new unit of account, which helped lead to banking. Archimedes' principle provided the next link: coins could now be easily tested for their fine weight of the metal, and thus the value of a coin could be determined, even if it had been shaved, debased or otherwise tampered with (see Numismatics).

In most major economies, using coinage, copper, silver, and gold formed three tiers of coins. Gold coins were used for large purchases, payment of the military, and backing of state activities. Silver coins were used for midsized transactions, and as a unit of account for taxes, dues, contracts, and fealty, while copper coins represented the coinage of common transactions. This system had been used in ancient India since the time of the Mahajanapadas. In Europe, this system worked through the medieval period because there was virtually no new gold, silver, or copper introduced through mining or conquest. Thus the overall ratios of the three coinages remained roughly equivalent.

Paper

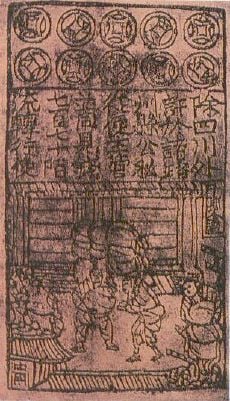

In premodern China, the need for credit and for circulating a medium that was less of a burden than exchanging thousands of copper coins led to the introduction of paper money. This economic phenomenon was a slow and gradual process that took place from the late Tang dynasty (618–907) into the Song dynasty (960–1279). It began as a means for merchants to exchange heavy coinage for receipts of deposit issued as promissory notes from shops of wholesalers, notes that were valid for temporary use in a small regional territory. In the 10th century, the Song dynasty government began circulating these notes amongst the traders in their monopolized salt industry. The Song government granted several shops the sole right to issue banknotes, and in the early 12th century the government finally took over these shops to produce state-issued currency. Yet the banknotes issued were still regionally valid and temporary; it was not until the mid 13th century that a standard and uniform government issue of paper money was made into an acceptable nationwide currency. The already widespread methods of woodblock printing and then Pi Sheng's movable type printing by the 11th century was the impetus for the massive production of paper money in premodern China.

At around the same time in the medieval Islamic world, a vigorous monetary economy was created during the 7th–12th centuries on the basis of the expanding levels of circulation of a stable high-value currency (the dinar). Innovations introduced by economists, traders and merchants of the Muslim world include the earliest uses of credit,[36] cheques, savings accounts, transactional accounts, loaning, trusts, exchange rates, the transfer of credit and debt,[37] and banking institutions for loans and deposits.[37]

In Europe, paper money was first introduced in Sweden in 1661. Sweden was rich in copper, thus, because of copper's low value, extraordinarily big coins (often weighing several kilograms) had to be made. The advantages of paper currency were numerous: it reduced transport of gold and silver, and thus lowered the risks; it made loaning gold or silver at interest easier since the specie (gold or silver) never left the possession of the lender until someone else redeemed the note; and it allowed for a division of currency into credit and specie backed forms. It enabled the sale of stock in joint stock companies, and the redemption of those shares in the paper.

However, these advantages are held within their disadvantages. First, since a note has no intrinsic value, unethical authorities printed more of it than they had specie to back it with. Second, because it increased the money supply, it increased inflationary pressures, a fact observed by David Hume in the 18th century. Thus, paper money would often lead to an inflationary bubble, which could collapse if people began demanding hard money, causing the demand for paper notes to fall to zero. The printing of paper money was also used for financing wars. It was also possible to counterfeit. For these reasons, paper currency was held in suspicion and hostility. It has been widely misused since the speculative profits of trade and capital creation were quite large. Major nations established mints to print money and mint coins, and branches of their treasury to collect taxes and hold gold and silver stock.

Both silver and gold have been legal tender and accepted by governments for taxes. However, the instability in the ratio between the two grew over the 19th century, with the increase in the supply of these metals, particularly silver, and of trade. Bimetallism attempts to create a standard where both gold and silver-backed currency remain in circulation.

By 1900, most industrial nations were on some form of a gold standard, with paper notes and silver coins constituting the circulating medium. Private banks and governments worldwide followed Gresham's law: keeping gold and silver paid but paying out in notes. Gradually floating fiat currencies came into force. One of the last countries to break away from the gold standard was the United States in 1971.

Commercial bank money creation

Commercial bank money or demand deposits are claims against financial institutions that can be used to purchase goods and services. A demand deposit account is an account from which funds can be withdrawn at any time by check or cash withdrawal without giving the bank or financial institution any prior notice. Banks are legally obligated to return funds held in demand deposits immediately upon demand (or 'at call'). Demand deposit withdrawals can be performed in person, via checks or bank drafts, using automatic teller machines (ATMs), or through online banking.[38]

New commercial bank money is created through fractional-reserve banking, the banking practice where banks keep only a fraction of their deposits in reserve (as cash and other highly liquid assets) and lend out the remainder while maintaining the obligation to redeem all these deposits upon demand.[39][40] Commercial bank money differs from commodity and fiat money in two ways: firstly it is non-physical, as its existence is only reflected in the account ledgers of banks and other financial institutions, and secondly, there is some element of risk that the claim will not be fulfilled if the financial institution becomes insolvent. The process of fractional-reserve banking has a cumulative effect of money creation by commercial banks, as it expands the money supply (cash and demand deposits) beyond what it would otherwise be. Because of the prevalence of fractional reserve banking, the broad money supply of most countries is a multiple (greater than 1) of the amount of base money created by the country's central bank. That multiple (called the money multiplier) is determined by the reserve requirement or other financial ratio requirements imposed by financial regulators.

Digital or electronic

The development of computer technology in the second part of the twentieth century allowed money to be represented digitally. By 1990, in the United States all money transferred between its central bank and commercial banks was in electronic form. By the 2000s, most money existed as digital currency in bank databases.[41] In 2012, by the number of transactions, 20 to 58 percent of transactions were electronic (dependent on country).[42]

Anonymous digital currencies were developed in the early 2000s. Early examples include Ecash, bit gold, RPOW, and b-money. Not much innovation occurred until the conception of Bitcoin in 2008, which introduced the concept of a decentralized currency using blockchain technology that requires no trusted third party.[43] Bitcoin threatens national currencies by avoiding the corruption of government central banks, and it is used on black markets to evade government tracking of transactions. This caused the development of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), where governments can track every transaction.

Monetary policy

When gold and silver are used as money, the money supply can grow only as the supply of these metals is increased by mining. This rate of increase during gold rushes and discoveries causing inflation as the value of gold goes down. If the rate of gold mining cannot keep up with the growth of the economy, gold becomes relatively more valuable, and prices (denominated in gold) will drop, causing deflation. Deflation was common when gold and paper money backed by gold were used as money in the 18th and 19th centuries. Thus, while the money had intrinsic value, it did not allow for natural economic expansion with monetary stability.

Monetary systems based on fiat money and fractional reserve lending can avoid this problem, as money can be created as people want to build and create businesses. When loans are repaid, the money supply decreases. The central bank can issue the needed amount of currency in circulation to keep the value of money stable. Monetary policy is when the monetary authority manages the money supply.

This management process gets more complex when governments and financial institutions receive nonproductive loans, i.e., loans used for fighting wars or speculating with secondary financial instruments, sub-prime mortgages, and other risky investments. Such nonproductive loans cause inflation and shift wealth from producers to nonproducers. The monetary policy then has to control inflationary pressures from money creation not backed by real economic expansion. A further complication is when private central banks charge interest on new money for their profit, shifting wealth from society to the central bank owners and causing states to stay in debt. This is the situation with the Federal Reserve System in the United States. The Federal Reserve Act that the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee should seek "to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates."[44] These goals are at cross-purposes and require a balancing act that pits economic growth against a targeted 2% inflation rate to allow for nonproductive new money. The insatiable appetite of governments and financial industries engaged in the nonproductive use of reserves caused this system to break in 1932. This was curtailed by the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which restrained bank speculating, and unleashed when the Act was repealed in 1999. The World Comm, Enron, and other scandals immediately followed in 2002, followed by the financial collapse and bailout of 2007-2008. However, rather than reinstating the Glass-Steagall Act, as the former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker recommended,[45] the banks drafted laws that consolidated the big banks without addressing unsustainable government debt.

A failed monetary policy can cause hyperinflation, stagflation, recession, high unemployment, shortages of imported goods, inability to export goods, government collapse, and total monetary collapse as happened in Russia, for instance, after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Governments and central banks have taken regulatory and free market approaches to monetary policy. Some of the tools used to control the money supply include:

- changing the interest rate at which the central bank loans money to (or borrows money from) the commercial banks

- currency purchases or sales

- increasing or lowering government borrowing

- increasing or lowering government spending

- manipulation of exchange rates

- raising or lowering bank reserve requirements

- regulation or prohibition of private currencies

- taxation or tax breaks on imports or exports of capital into a country

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve is responsible for controlling the money supply, while in the Euro area the respective institution is the European Central Bank. Other central banks with a significant impact on global finances are the Bank of Japan, People's Bank of China, and the Bank of England.

For many years monetary policy was influenced by an economic theory known as monetarism. Monetarism argues that management of the money supply should be the primary means of regulating economic activity. The stability of the demand for money before the 1980s was a key finding of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz[46] supported by the work of David Laidler,[47] and others. The nature of the demand for money changed during the 1980s owing to technical, institutional, and legal factors, such as supply-side economics, and the influence of monetarism has since decreased.

Financial crimes

Counterfeiting

Counterfeit money is imitation currency produced without the legal sanction of the state or government. Producing or using counterfeit money is a form of fraud or forgery. Counterfeiting is almost as old as money itself. Plated copies (known as Fourrées) have been found of Lydian coins which are thought to be among the first western coins.[48] Historically, objects that were difficult to counterfeit (e.g. shells, rare stones, precious metals) were often chosen as money.[49] Before the introduction of paper money, the most prevalent method of counterfeiting involved mixing base metals with pure gold or silver.

A form of counterfeiting is the production of documents by legitimate printers in response to fraudulent instructions. During World War II, the Nazis forged British pounds and American dollars. Today some of the finest counterfeit banknotes are called Superdollars because of their high quality and likeness to the real U.S. dollar. There has been significant counterfeiting of Euro banknotes and coins since the launch of the currency in 2002, but considerably less than for the U.S. dollar.[50]

Another form of counterfeiting, sometimes known as creating funny money, is when the central bank increases the legal money supply for nonproductive purposes like many government loans. This causes inflation and a government debt burden on the citizens, so it is legal but not ethical. This problem can be solved when laws prevent a central bank from lending money, buying securities, or charging interest, acting as an economic agent. A limitation on the role of a central bank as a referee that performs services for a fee can prevent corruption in modern central bank/government cabals. These services include an exchange bank, a clearing house, and a money supply manager.

Money laundering

Money laundering is the process in which the proceeds of crime are transformed into ostensibly legitimate money or other assets. However, in several legal and regulatory systems, the term money laundering has become conflated with other forms of financial crime and sometimes used more generally to include misuse of the financial system (involving things such as misdirected government funds, creating money with risky securities, digital currencies, credit cards, and traditional currency), including terrorism financing, tax evasion, and evading of international sanctions.

Conclusion

"The great trouble is that money wasn’t allowed to develop. After two or three hundred years of the use of coins, governments stopped any further developments. We were not allowed to experiment on it, so money hasn’t been improved; it has rather become worse in the course of time.… Money was frozen in its most primitive form. What we have had since was mostly government abuses of money."—F.A. Hayek [51]

The evolution of money has shown that money as a medium of exchange works better as an accounting unit rather than being tied to precious metals whose supply never matches economic development demands. A currency that represents real economic growth, combined with regulated and insured fractional reserve banking, can automatically adjust to market demands and escape the swings of inflation that come from precious metal-backed money or new money created from nonproductive loans. Unfortunately, attempts to rein in the nonproductive lending of central banks and speculation in financial industries by government laws have been illusive. The Glass-Steagall Act, passed during the extreme economic crisis of the Great Recession, restrained financial speculation for over 60 years until 1999 when banks in the U.S. pressured the government for its repeal. Later financial crises led to laws created by the banks that made the long-term stability of the U.S. dollar unlikely.

However, greater economic reform is required than reinstating the Glass-Steagall act, which limited the role of commercial banks. Central banks should also be limited to the role of an economic referee engaged in managing the money supply, servicing banks, and regulating foreign exchange. This would eliminate conflicts of interest associated with central bank lending, buying and selling securities and assets, storing reserves, and charging interest that debt finances the economy. A separation of government from the economy parallel to the separation of church and state would dramatically reduce the control of government by the banking sector and the temptation of governments to create funny money to finance wars.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Mishkin, Frederic S. (2007). The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, Alternate, Boston: Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-42177-7.

- ↑ What Is Money? {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}} By John N. Smithin. Retrieved July-17-09.

- ↑ money : The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mankiw, N. Gregory (2007). "2", Macroeconomics, 6th, New York: Worth Publishers, 22–32. ISBN 978-0-7167-6213-3.

- ↑ The three primary spheres of society are based on three spontaneous orders that evolve in any human community—language, money, and law. James U. Blanchard III and F. A. Hayek, “Exclusive Interview with F.A. Hayek,” Cato Institute Policy Report, May-June 1984. https://www.cato.org/policy-report/may/june-1984/exclusive-interview-fa-hayek#

- ↑ Hayek argues that it is a natural "spontaneous" social instituion. James U. Blanchard III and F. A. Hayek, “Exclusive Interview with F.A. Hayek,” Cato Institute Policy Report, May-June 1984. https://www.cato.org/policy-report/may/june-1984/exclusive-interview-fa-hayek#

- ↑ What is Debt? – An Interview with Economic Anthropologist David Graeber. Naked Capitalism (2011-08-26).

- ↑ David Graeber: Debt: The First 5000 Years, Melville 2011. Cf. review {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}

- ↑ David Graeber (2001). Toward an anthropological theory of value: the false coin of our own dreams. Palgrave Macmillan, 153–154. ISBN 978-0-312-24045-5.

- ↑ Kramer, History Begins at Sumer, pp. 52–55.

- ↑ Herodotus. Histories, I, 94

- ↑ Goldsborough, Reid (2003-10-02). World's First Coin. rg.ancients.info.

- ↑ Moshenskyi, Sergii (2008). History of the weksel: Bill of exchange and promissory note. ISBN 978-1-4363-0694-2.

- ↑ Marco Polo (1818). The Travels of Marco Polo, a Venetian, in the Thirteenth Century: Being a Description, by that Early Traveller, of Remarkable Places and Things, in the Eastern Parts of the World, 353–355.

- ↑ Gordon L. Anderson, Integral Society: Social Institutions and Individual Sovereignty (St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2023), pp. 113-115.

- ↑ Stephen Quinn and William Roberds, “Death of a Reserve Currency,” International Journal of Central Banking, December 2016, pp. 63-103.

- ↑ (2012) Modern money theory: a primer on macroeconomics for sovereign monetary systems. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 45–50. ISBN 978-0230368897.

- ↑ Milnes, Alfred (1919). The economic foundations of reconstruction. Macdonald and Evans.

- ↑ Dwivedi, DN (2005). Macroeconomics: Theory and Policy. Tata McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Krugman, Paul & Wells, Robin, Economics, Worth Publishers, New York (2006)

- ↑ (2005) "7", Macroeconomics, 5th, Pearson, 266–269. ISBN 978-0-201-32789-2.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 T.H. Greco. Money: Understanding and Creating Alternatives to Legal Tender, White River Junction, Vt: Chelsea Green Publishing (2001). ISBN 1-890132-37-3

- ↑ Functions of Money (2017-10-11).

- ↑ What is Money?. International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Money. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

- ↑ (2006) The Little Money Book. The Disinformation Company. ISBN 978-1-932857-26-9.

- ↑ History of Money.

- ↑ Bernstein, Peter, A Primer on Money and Banking, and Gold, Wiley, 2008 edition, pp. 29–39

- ↑ Mises, Ludwig von. The Theory of Money and Credit, (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, Inc., 1981), trans. H. E. Batson. Ch.3 Part One: The Nature of Money, Chapter 3: The Various Kinds of Money, Section 3: Commodity Money, Credit Money, and Fiat Money, Paragraph 25.

- ↑ Jevons, William Stanley (1875). "XVI: Representative Money", Money and the Mechanism of Exchange. ISBN 978-1-59605-260-4.

- ↑ Deardorff, Prof. Alan V. (2008). Deardorff's Glossary of International Economics. Department of Economics, University of Michigan.

- ↑ Black, Henry Campbell (1910). A Law Dictionary Containing Definitions Of The Terms And Phrases Of American And English Jurisprudence, Ancient And Modern, p. 494. West Publishing Co. Black’s Law Dictionary defines the word "fiat" to mean "a short order or warrant of a Judge or magistrate directing some act to be done; an authority issuing from some competent source for the doing of some legal act"

- ↑ usmiNT.gov . Retrieved July-18-09.

- ↑ Tom Bethell. "Crazy as a Gold Bug", New York, New York Media, 1980-02-04, p. 34. Retrieved July-18-09

- ↑ Shredded & Mutilated: Mutilated Currency, Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ Banaji, Jairus (2007). Islam, the Mediterranean and the Rise of Capitalism. Historical Materialism 15 (1): 47–74.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Labib, Subhi Y. (March 1969). Capitalism in Medieval Islam. The Journal of Economic History 29 (1): 79–86.

- ↑ (2003) Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-063085-8.

- ↑ The Bank Credit Analysis Handbook: A Guide for Analysts, Bankers, and Investors by Jonathan Golin. Publisher: John Wiley & Sons (2001). ISBN 978-0-471-84217-0

- ↑ Economic Definitions.

- ↑ How Currency Works (2 September 2003).

- ↑ Eveleth, Rose. The truth about the death of cash.

- ↑ Wallace, Benjamin. "The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin", Wired, 23 November 2011.

- ↑ The Federal Reserve. 'Monetary Policy and the Economy". (PDF) Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, (2005-07-05). Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Gordon L. Anderson, Integral Society: Social Institutions and Individual Sovereignty (St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2023), p. 119.

- ↑ (1971) Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00354-2.

- ↑ (1997) Money and Macroeconomics: The Selected Essays of David Laidler (Economists of the Twentieth Century). Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85898-596-1.

- ↑ A Case for the World's Oldest Coin.

- ↑ (2019)The International Monetary and Financial System. Annual Review of Economics 11 (1): 859–893.

- ↑ Counterfeiting statistics for several currencies. Itsamoneything.com (2012-06-09).

- ↑ Friedrich A. Hayek. Interview by James U. Blanchard III, May 1, 1984. Cato Institute Policy Report May/June 1984. https://www.cato.org/policy-report/may/june-1984/exclusive-interview-fa-hayek#.

Further reading

- Chown, John F. A History of Money: from AD 800 (Psychology Press, 1994).

- Davies, Glyn, and Duncan Connors. A History of Money (4th ed. U of Wales Press, 2016) excerpt .

- Ferguson, Niall. The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World (2009) excerpt

- Keen, Steve (February 2015). "What Is Money and How Is It Created?" argues, "Banks create money by issuing a loan to a borrower; they record the loan as an asset, and the money they deposit in the borrower’s account as a liability. This, in one way, is no different to the way the Federal Reserve creates money ... money is simply a third party’s promise to pay which we accept as full payment in exchange for goods. The two main third parties whose promises we accept are the government and the banks ... money ... is not backed by anything physical, and instead relies on trust. Of course, that trust can be abused ... we continue to ignore the main game: what the banks do (for good and for ill) that really drives the economy." Forbes

- Kuroda, Akinobu. A Global History of Money (Routledge, 2020). excerpt

- Hartman, Mitchell, "How Much Money Is There in the World?", Marketplace, American Public Media, October 30, 2017.

- Lanchester, John, "The Invention of Money: How the heresies of two bankers became the basis of our modern economy", The New Yorker, 5 & 12 August 2019, pp. 28–31.

- Weatherford, Jack. The history of money (2009). by a cultural anthropologist. excerpt

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.