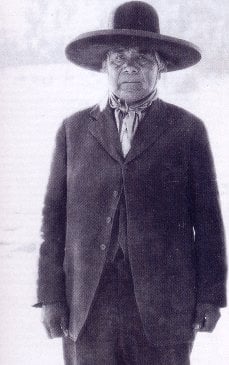

Wovoka

Wovoka (c. 1856 - September 20, 1932), also known as Jack Wilson, was the Northern Paiute mystic who founded the Ghost Dance movement.

Having spent part of his childhood with a family of white ranchers, Wovoka was well versed in both the English language and the Christian religion. Returning to his Paiute roots as a young adult, he gained respect as a shaman. At about the age of 30, he began weaving together beliefs from a number of Native visionaries, as well as from his earlier immersion into Christianity. From this the Ghost Dance religion came into being and swiftly swept throughout much of the American West, from the Central Plains to the Pacific Ocean.

Wovoka prophesied an end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and peace between whites and Indians. As it spread from its original source, various Native American tribes synthesized selected aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, creating changes in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself. The Sioux adaptation of the Ghost Dance subsequently led to the massacre at Wounded Knee.

After this tragedy, the religion lost its following, as did Wovoka. He died in relative obscurity in Yerington, Nevada on September 20, 1932 and is interred in the Paiute Cemetery in the town of Schurz.

Early life

Wovoka was born in the Smith Valley area of western Nevada around the year 1856. It is believed that his father may have been the religious leader variously known as ‚ÄúTavibo‚Äú or ‚ÄúNumu-Taibo,‚ÄĚ whose teachings were similar to those of Wovoka.

Little else is known about his early life, only that when he was about 14 years‚Äďof‚Äďage his father died, leaving Wovoka to be raised by the family of David Wilson, a nearby white rancher. Wovoka worked on Wilson‚Äôs ranch, taking the the name Jack Wilson, especially when dealing with whites. He was eventually broadly known by this name within the Indian community as well.

Wovoka learned to speak English while on the Wilson ranch. He also studied Christian theology with the deeply religious David Wilson. Wovoka eventually left the Wilson household and returned to live among the Paiute.

Life among the Paiute

The Northern Paiutes living in Mason Valley, Nevada thrived on a subsistence pattern of foraging for cyperus bulbs for part of the year and augmenting their diets with fish, pine nuts, and occasionally wild game. Their social system had little hierarchy and relied instead on shamans who as self-proclaimed spiritually-blessed individuals organized events for the group as a whole. Usually, community events centered on the observance of a ritual at prescribed times of year, such as harvests or hunting parties.

A devastating typhoid epidemic struck in 1867. This, and other European diseases, killed approximately one-tenth of the total population, resulting in widespread psychological and emotional trauma, which brought grave disorder to the economic system preventing many families from continuing their nomadic lifestyle.

Visions and prophesy

Wovoka gained a reputation as a powerful shaman early in adulthood. He became known in Mason Valley as a gifted young leader. He often presided over circle dances, while preaching a message of universal love. At about the age of thirty, he began to weave together various cultural strains into the Ghost Dance religion. The beliefs were incorporated from those of a number of Native visionaries seeking relief from the hardships that accompanied the spreading white civilization, as well as from his earlier immersion into Christianity.

Wovoka was believed to have experienced a vision during a solar eclipse on January 1, 1889. According the report of Anthropologist James Mooney, who conducted an interview with Wilson in 1892, Wilson had stood before God in Heaven, and had seen many of his ancestors engaged in their favorite pastimes. God showed Wilson a beautiful land filled with wild game, and instructed him to return home to tell his people that they must love each other, not fight, and live in peace with the whites. God also stated that Wilson's people must work, not steal or lie, and that they must not engage in the old practices of war or the self-mutilation traditions connected with mourning the dead. God said that if his people kept by these rules, they would be united with their friends and family in the other world.

Ghost dance

According to Wilson, he was then given the formula for the proper conduct of the Ghost Dance and commanded to bring it back to his people. Wilson preached that if this five-day dance was performed in the proper intervals, the performers would secure their happiness and hasten the reunion of the living and deceased. Wilson claimed to have left the presence of God convinced that if every Native American in the West danced the new dance to ‚Äúhasten the event,‚ÄĚ all evil in the world would be swept away leaving a renewed Earth filled with food, love, and faith. Quickly accepted by his Paiute brethren, the new religion was termed ‚ÄúDance In A Circle." Because the first white contact with the practice came by way of the Sioux, their expression "Spirit Dance" was adopted as a descriptive title for all such practices. This was subsequently translated as "Ghost Dance."

Wovoka prophesied an end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and peace between whites and Indians. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As it spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selected aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, creating changes in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself.

Ghost dance and the Sioux

The Ghost Dance took on a more militant character among the Lakota Sioux who were suffering under the disastrous US government policy that had sub-divided their original reservation land and forced them to turn from a hunter-gatherer way of life to agriculture. By performing the Ghost Dance, the Lakota believed they could take on a "Ghost Shirt" capable of repelling the white man's bullets. Another Lakota interpretation of Wovoka's religion is drawn from the idea of a "renewed Earth," in which "all evil is washed away." This Lakota interpretation included the removal of all white people from their lands, unlike Wovoka's version of the Ghost Dance, which encouraged co-existence with whites. Seeing the Ghost Dance as a threat and seeking to suppress it, U.S. Government Indian agents initiated actions that tragically culminated with the death of Sitting Bull and the later Wounded Knee massacre.

After that tragedy, the Ghost Dance and its ideals as taught by Wovoka soon began to lose energy and it faded from the scene, although some tribes still practiced into the twentieth century.

Wovoka's legacy

Wovoka's teachings included messages of non-violence and bore a striking resemblance to Christian teachings. He preached such concepts as immortality and pacifism, and often referred to "the messiah who came once to live on earth with the white man but was killed by them" (Jesus).

The re-interpretation of his teachings, emphasizing the possible elimination of Whites, created the misunderstanding of the Ghost Dance as an expression of Indian militancy. This, coupled with the rapid rise in popularity of the Ghost Dance among tribes scattered between the Central Plains and the Pacific Ocean, contributed to the fear among the already defensive federal officials.

Following the tragedy at Wounded Knee, Wovoka lost his following. He lived quietly as Jack Wilson until September 1932. He had been virtually forgotten by both whites and Indians. The Ghost Dance itself was abandoned until the 1970s, when it was revived through the Native American activist movement.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Dee. 1970. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books: Henry Holt. ISBN 0805010459

- Hittman, Michael, and Don Lynch. 1997. Wovoka and the Ghost Dance. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803273088

- Norman, John. 1979. Ghost dance. New York, NY: DAW Books. ISBN 0879975016

- Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). 2004. Wovoka, Jack Wilson 1856-1932 PBS. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- Toledo, Robert A. 2007. Wovoka the Paiute Messiah. Viewzone. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved May 20, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.