Prayer is a form of religious practice that seeks to activate a volitional connection to some greater power in the universe through deliberate intentional practice. Prayer may be either individual or communal and take place in public or in private. It may involve the use of words, song, or complete silence. When language is used, prayer may take the form of a hymn, incantation, formal creedal statement, or a spontaneous utterance in the praying person. There are different forms of prayer such as petitionary prayer, prayers of supplication, thanksgiving, and worship/praise. Prayer may be directed towards a deity, spirit, deceased person, or lofty idea, for the purpose of worshiping, requesting guidance, requesting assistance, confessing sins or to express one's thoughts and emotions. Thus, people pray for many reasons such as personal benefit or for the sake of others.

The act of prayer is attested in written sources as early as 5000 years ago. Some anthropologists believe that the earliest intelligent modern humans practiced something that we would recognize today as prayer. Prayer is still a very common practice in the modern world.

Etymology

The English word "prayer" derives from the Old French preier (meaning: "to request"). From classical times, it was used in both religious and secular senses: precor include "to wish well or ill to any one," "to hail, salute," or "address one with a wish." The Latin orare "to speak" later took over the role of precari to mean "pray." Closely related is the Portuguese perguntar, "to ask" and by extension "ask for." Pray is akin to Sanskrit roots, pracch- prask-, pras "interrogation," and prcchati "he asks".

Forms of prayer

The great spiritual traditions offer a wide variety of devotional acts. There are morning and evening prayers, graces said over meals, and reverent physical gestures. Some Christians bow their heads and fold their hands. Native Americans dance. Some Sufis whirl. Hindus often chant mantras. Orthodox Jews sway their bodies back and forth. Quakers keep silent. Among these methodologies are a variety of approaches to understanding prayer:

- The belief that the finite can actually communicate with the infinite;

- The belief that the infinite is interested in communicating with the finite;

- The belief that the prayer is listened to, and may, or may not get a response;

- The belief that prayer is intended to inculcate certain attitudes in the one who prays, rather than to influence the recipient;

- The belief that prayer is intended to train a person to focus on the recipient through philosophy and intellectual contemplation;

- The belief that prayer is intended to enable a person to gain a direct experience of the recipient;

- The belief that prayer is intended to affect the very fabric of reality itself;

- The belief that the recipient expects or appreciates prayer

The act of prayer

Praying has many different forms. Prayer may be done privately and individually, or it may be done corporately in the presence of fellow believers. Prayer can be incorporated into a daily "thought life," in which one is in constant communication with a God. Some people pray throughout all that is happening during the day and seek guidance as the day progresses. There can be many different answers to prayer, just as there are many ways to interpret an answer to a question, if there in fact comes an answer. Some may experience audible, physical, or mental epiphanies. If indeed an answer comes, the time and place it comes is considered random. Some outward acts that sometimes accompany prayer are: anointing with oil; ringing a bell; burning incense or paper; lighting a candle or candles; facing a specific direction (i.e. towards Mecca or the East); making the sign of the cross. One less noticeable act related to prayer is fasting.

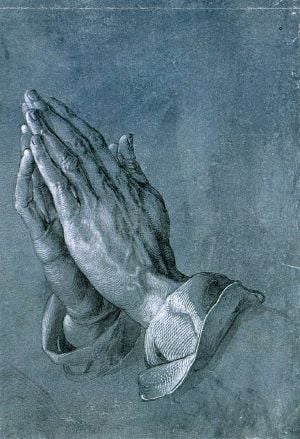

A variety of body postures may be assumed, often with specific meaning (mainly respect or adoration) associated with them: standing; sitting; kneeling; prostrate on the floor; eyes opened; eyes closed; hands folded or clasped; hands upraised; holding hands with others; a laying on of hands and others. Prayers may be recited from memory, read from a book of prayers, or composed spontaneously as they are prayed. They may be said, chanted, or sung. They may be with musical accompaniment or not. There may be a time of outward silence while prayers are offered mentally. Often, there are prayers to fit specific occasions, such as the blessing of a meal, the birth or death of a loved one, other significant events in the life of a believer, or days of the year that have special religious significance. Details corresponding to specific traditions are outlined below.

Prayer in Abrahamic religions

Judaism

In ancient times, communal prayer in Judaism was closely related to the performance of ritual sacrifice at the Temple of Jerusalem. Since the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E., however, Jewish prayer has tended to revolve around understanding the Torah as the Word of God and commemorating Jewish festivals. Rabbinical Judaism made it customary for Jews to pray three times a day, and more on special days, such as the Shabbat and Jewish holidays. The siddur is the prayerbook used by Jews the world over, containing a set order of daily prayers. Jewish prayer is usually described as having two aspects: kavanah (intention) and keva (the ritualistic, structured elements).

The most important Jewish prayers are the Shema Yisrael ("Hear O Israel") and the Amidah ("the standing prayer").

Communal prayer is preferred over solitary prayer, and a quorum of 10 adults males (a minyan) is considered a prerequisite for several communal prayers.

The largest book in the Bible is the Book of Psalms, 150 religious songs which are also prayers. Other well-known Biblical prayers include the Song of Moses (Exodus 15:1-28), the Song of Hannah (1 Samuel 2:1-8), and the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55).

Christianity

According to the Bible, Jesus instructed his disciples to pray in the following way:

|

Matthew 6:9–13 (KJV)

|

Luke 11:2–4 (KJV)

|

This prayer, known as the Lord's Prayer, is the most common and universal prayer among Christians. Two versions of it occur in the New Testament, one in the Gospel of Matthew Matthew 6:9–13 in the Sermon on the Mount, and the other in the Gospel of Luke Luke 11:2–4. All these versions are based on the text in Matthew, rather than Luke, of the prayer given by Jesus.

Other popular forms of Christian prayer include the Rosary (in Roman Catholicism) and the Jesus Prayer (in Eastern Orthodoxy).

Christian prayers are very varied. They can be completely spontaneous, or read entirely from a text, like the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.

Christians may pray to God as a universal creator, or may pray to the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit (or some combination thereof). Some Christians (e.g., Catholics, Orthodox) will also ask the righteous in heaven and "in Christ" (such as Virgin Mary or other saints) to intercede on their behalf by praying to them. This doctrine is known as the "intercession of saints." Other formulaic closures include "through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever," and "in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit."

It is customary among Protestants to end prayers with "In Jesus' Name, Amen" or "In the name of Christ, Amen." However, the most commonly used closure in Christianity is simply "Amen" (from a Hebrew adverb used as a statement of affirmation or agreement, usually translated as so be it).

There is also the form of prayer called hesychast which is a repetitious type of prayer for the purpose of meditation.

Islam

Prayer (called salat in Arabic), is one of the Five Pillars of Islam. Muslims are required to pray five times a day facing the Kaaba in Mecca. There are also many standard duas or supplications in Arabic, to be recited at various times, (e.g., for one's parents, after salah, and before eating). Muslims may also say dua in their own words and languages for any issue they wish to communicate with God in the hope that God will answer their prayers.

The "call for prayer" (adhan or azaan) traditionally occurred from a minaret where the muezzin would call fellow Muslims to stand together for the prayer.

Bahá'í

Bahá'u'lláh, the Báb, and `Abdu'l-Bahá revealed many prayers for general use, and some for specific occasions, including for unity, detachment, spiritual upliftment, and healing among others. Bahá'ís are also required to recite each day one of three obligatory prayers revealed by Bahá'u'lláh. The believers have been enjoined to face in the direction of the Qiblih (Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, near `Akká, in present day Israel) when reciting their Obligatory Prayer. The longest obligatory prayer may be recited at any time during the day; another, of medium length, is recited once in the morning, once at midday, and once in the evening; and the shortest can be recited anytime between noon and sunset. Bahá'ís also read from and meditate on the scriptures every morning and evening.

Prayer in Eastern religions

Buddhism

In certain Buddhist sects, prayer accompanies meditation. Buddhism for the most part sees prayer as a secondary, supportive practice to meditation and scriptural study. Gautama Buddha claimed that human beings possess the capacity and potential to be liberated, or enlightened, through contemplation, leading to insight. Prayer is seen mainly as a powerful psycho-physical practice that can enhance meditation.

- In the earliest Buddhist tradition, the Theravada, and in the later Mahayana tradition of Zen (or Chán), prayer plays only an ancillary role. It is largely a ritual expression of wishes for success in personal practice and in helping all beings. However, it can also be a way of expressing respect and appreciation to the individual person of the Buddha, who is said to still exist though in a higher dimension.

- The Mahayana tradition of Tibetan Buddhism emphasizes an instructive and devotional relationship to a guru; this may involve devotional practices similar to prayer. It also posits the existence of various deities. How practitioners relate to them will depend upon the 'level' at which they are practicing. At one level, one may pray to a deity for protection or assistance, taking a more subordinate role. At another level, one may invoke the deity, on a more equal footing. At a higher level. one may deliberately cultivate the idea that one has 'become' the deity, whilst remaining aware that its ultimate nature is sunyata.

- Pure Land Buddhism emphasizes the recitation of prayer-like mantras by devotees. On one level it is said that reciting these mantras can ensure rebirth into a spiritual 'pure land' after death, where one may work further towards one's enlightenment with greater ease. On another level, the practice is a form of meditation aimed at achieving realization.

Beyond all these practices, the Buddha emphasized the primacy of individual practice and experience. He said that supplication to gods or deities was not necessary. Nevertheless, today many lay people in East Asian countries pray to the Buddha in ways that resemble Western prayer - asking for intervention and offering devotion.

Hinduism

Hinduism has incorporated many kinds of prayer (Sanskrit: prārthanā), from fire-based rituals to philosophical musings. While chanting involves 'by dictum' recitation of timeless verses, dhyanam involves deep meditation (however short or long) on the preferred deity/God. Again the object to which prayers are offered could be persons, murtis, mantras, concepts, or simply plain formless meditation as practiced by the ancient sages. All of these are directed to fulfilling personal needs or deep spiritual enlightenment. Ritual invocation was part and parcel of the Vedic religion and as such permeated their sacred texts. Indeed, the highest sacred texts of the Hindus, the Vedas, are a large collection of mantras and prayer rituals. Classical Hinduism came to focus on extolling a single supreme force, Brahman, that is made manifest in several lower forms as the familiar gods of the Hindu pantheon. Hindus in India have numerous devotional movements. Hindus may pray to the highest absolute God Brahman, or more commonly to its manifestations. Typically, Hindus pray with their hands (the palms) joined together. The hand gesture is similar to the popular Indian greeting namaste.

Jainism

Although Jains believe that no spirit or divine being can assist them on their path, they do hold some influence, and on special occasions, Jains will pray for right knowledge to the twenty-four Tirthankaras (saintly teachers) or sometimes to Hindu deities such as Ganesha.

Shinto

The practices involved in Shinto prayer are heavily influenced by Buddhism; Japanese Buddhism has also been strongly influenced by Shinto in turn. The most common and basic form of devotion involves throwing a coin, or several, into a collection box, ringing a bell, clapping one's hands, and contemplating one's wish or prayer silently. The bell and hand clapping are meant to wake up or attract the attention of the kami of the shrine, so that one's prayer may be heard.

Shinto prayers quite frequently consist of wishes or favors asked of the kami, rather than lengthy praises or devotions. Unlike in certain other faiths, it is not considered irregular or inappropriate to ask favors of the kami in this way, and indeed many shrines are associated with particular favors, such as success on exams.

In addition, one may write one's wish on a small wooden tablet, called an ema, and leave it hanging at the shrine, where the kami can read it. If the wish is granted, one may return to the shrine to leave another ema as an act of thanksgiving.

Approaches to prayer

Direct petitions to God

From biblical times to today, the most common form of prayer is to directly appeal to God to grant one's requests called "petitionary prayers." This in many ways is the simplest form of prayer. In this view, a person directly confronts God in prayer, and asks for their needs to be fulfilled. God listens to the prayer, and may or may not choose to answer in the way one asks of Him. This is the primary approach to prayer found in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, most of the Church writings, and in rabbinic literature such as the Talmud.

Prayers of Thanksgiving

A second type of prayer involves prayers of gratitude for the divine's blessings on humanity and in one's life. This type of prayer expresses thanksgiving for God's gifts and is especially praised in various religions because it shows appreciation to God.

Prayers of Worship

A third type of prayer involves praise and worship directed towards a divine being. This type of prayer is a highly devotional and seeks to glorify the divine being without asking for any rewards. Sometimes this form of prayer will concentrate on repition of the name of God (such as nam simran or Jap in Sikhism), or focus on God's glorious attributes or names.

Educational prayers

In this view, prayer is meant to inculcate certain attitudes in the one who prays, but not to influence. Among Jews, this has been the approach of Rabbenu Bachya, Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, Joseph Albo, Samson Raphael Hirsch, and Joseph B. Soloveitchik. This view is expressed by Rabbi Nosson Scherman in the overview to the Artscroll Siddur ( XIII).

Mystical prayers

For many mystics, the purpose of prayer is to enable the person praying to gain a direct experience of the recipient of the prayer (or as close to direct as a specific theology permits). This approach is very significant in Christianity and widespread in Judaism (although less popular theologically). In Eastern Orthodoxy, this approach is known as hesychasm. It is also widespread in Sufi Islam, and in some forms of mysticism. It has some similarities with the rationalist approach, since it can also involve contemplation, although the contemplation is not generally viewed as being as rational or intellectual. It also has some similarities with the Kabbalistic view, but it lacks the Kabbalistic emphasis on the importance of individual words and letters.

Adherents of Kabbalah (esoteric Jewish mysticism) base their prayers on those found in the siddur, the traditional Jewish prayer text. However, they add to these prayers a number of kavanot, mystical statements of intention. Prayer affects the very fabric of reality itself, restructuring and repairing the universe in a real fashion. For Kabbalists, every prayer, every word of every prayer, and indeed, even every letter of every word of every prayer, has a precise meaning and a precise effect.

In Kabbalah and related mystical belief systems, adherents claim intimate knowledge about the way in which the divine relates to us and the physical universe in which we live. For people with this view, prayers can literally affect the mystical forces of the universe and repair the fabric of creation.

Ritual prayers

In many ancient religions, such as Vedic Hinduism, ceremonial prayers were highly formulaic and ritualized. The formalism and formulaic nature of these prayers led them to be written down in language that may have only been partially understood by the writers.

Prayers in Etruscan were used in the Roman world by augurs and other oracles long after Etruscan became a dead language. The Carmen Arvale and the Carmen Saliare are two specimens of partially preserved prayers that seem to have been unintelligible to their scribes, and whose language is full of archaisms and difficult passages.

Roman prayers and sacrifices were often envisioned as legal bargains between deity and worshipper. The Roman formula was do ut des: "I give, so that you may give in return." Cato the Elder's treatise on agriculture contains many examples of preserved traditional prayers; in one, a farmer addresses the unknown deity of a possibly sacred grove, and sacrifices a pig in order to placate the god or goddess of the place and beseech his or her permission to cut down some trees from the grove.

The rationalist approach

In this view, the ultimate goal of prayer is to help train a person to focus on divinity through philosophy and intellectual contemplation. This approach was taken by the Jewish scholar and philosopher Maimonides and the other medieval rationalists; it became popular in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic intellectual circles, but never became the most popular understanding of prayer among the laity in any of these faiths. In all three of these faiths today, a significant minority of people still hold to this approach.

Efficacy of prayer

In 1872, Francis Galton conducted a famous statistical experiment to determine whether or not prayer had a physical effect on the external environment. Galton hypothesized that if prayer was effective, members of the British Royal family would live longer, given that thousands prayed for their wellbeing every Sunday. He therefore compared longevity in the British Royal family with that of the general population, and found no difference.[1] While the experiment was probably intended to satirize, it set the precedent for a number of different studies, the results of which are contradictory.

Two studies claimed that patients who are being prayed for recover more quickly or more frequently although critics have claimed that the methodology of such studies are flawed, and the perceived effect disappears when controls are tightened.[2] One such study, with a double-blind design and about 500 subjects per group, suggested that intercessory prayer by born again Christians had a statistically significant positive effect on a coronary care unit population.[3] Critics contend that there were severe methodological problems with this study.[4] Another such study was reported by Harris, et al. [5] Critics also claim Byrd's 1988 study was not fully double-blinded, and that in the Harris study, patients actually had a longer hospital stay in the prayer group, if one discounts the patients in both groups who left before prayers began,[6] although the Harris study did demonstrate the prayed for patients on average received lower course scores (indicating better recovery).

One of the largest randomized, blind clinical trials was a remote retroactive intercessory prayer study conducted in Israel by Leibovici. This study used 3393 patient records from 1990-96, and blindly assigned some of these to an intercessory prayer group. The prayer group had shorter hospital stays and duration of fever.[7]

Several studies of prayer effectiveness have yielded null results.[8] A 2001 double-blind study of the Mayo Clinic found no significant difference in the recovery rates between people who were (unbeknownst to them) assigned to a group that prayed for them and those who were not.[9] Similarly, the MANTRA study conducted by Duke University found no differences in outcome of cardiac procedures as a result of prayer.[10] In another similar study published in the American Heart Journal in 2006, Christian intercessory prayer when reading a scripted prayer was found to have no effect on the recovery of heart surgery patients; however, the study found patients who had knowledge of receiving prayer had slightly higher instances of complications than those who did not know if they were being prayed for or those who did not receive prayer.[11][12]

Many accept that prayer can aid in recovery, not due to divine influence but due to psychological and physical benefits. It has also been suggested that if a person knows that he or she is being prayed for it can be uplifting and increase morale, thus aiding recovery. Many studies have suggested that prayer can reduce physical stress, regardless of the god or gods a person prays to, and this may be true for many worldly reasons. Other practices such as Yoga, Tai Chi, and Meditation may also have a positive impact on physical and psychological health.

Others feel that the concept of conducting prayer experiments reflects a misunderstanding of the purpose of prayer. The previously mentioned 2006 study published in the American Heart Journal indicated that some of the intercessors who took part in it complained about the scripted nature of the prayers that were imposed to them, saying that this is not the way they usually conduct prayer:

"Prior to the start of this study, intercessors reported that they usually receive information about the patient’s age, gender and progress reports on their medical condition; converse with family members or the patient (not by fax from a third party); use individualized prayers of their own choosing; and pray for a variable time period based on patient or family request."[11]

Deuteronomy 6:16 states, "You shall not test the Lord thy God"[13] reflecting the notion of some that prayer cannot, or should not, be tested.

Notes

- ↑ Francis Galton, Statistical inquiries into the efficacy of prayer Fortnightly Review 68 (1872):125-135. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ Prayer still useless Skeptico, July 20, 2005. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ R.C. Byrd, Positive therapeutic effects of intercessory prayer in a coronary care unit population South Med J. 81 (1988):826-829. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ Gary P. Posner, A critique of the San Francisco hospital study on intercessory prayer and healing Free Inquiry, Spring 1990. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ W.S. Harris, M. Gowda, J.W. Kolb, C.P. Strychacz, J.L. Vacek, P.G. Jones, A. Forker, J.H. O'Keefe, and B.D. McCallister, A randomized, controlled trial of the effects of remote, intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients admitted to the coronary care unit Arch Intern Med 159 (1999):2273-2278. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ I. Tessman and J. Tessman, Efficacy of Prayer: A Critical Examination of Claims Skeptical Inquirer (March/April 2000). Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ L. Leibovici, Effects of remote, retroactive intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients with bloodstream infection: randomized controlled trial BMJ 323 (2001): 1450-1451. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ S. O'Laoire, An experimental study of the effects of distant, intercessory prayer on self-esteem, anxiety, and depression, Altern Ther Health Med 3 (1997):38-53. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ J.M. Aviles, S.E. Whelan, D.A. Hernke, B.A. Williams, K.E. Kenny, W.M. O'Fallon, and S.L. Kopecky, Intercessory prayer and cardiovascular disease progression in a coronary care unit population: a randomized controlled trial Mayo Clin Proc 76 (2001):1192-1198. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ M.W. Krucoff, S.W. Crater, D. Gallup, J.C. Blankenship, M. Cuffe, M. Guarneri, R.A. Krieger, V.R. Kshettry, K. Morris, M. Oz, A. Pichard, M.H. Sketch, Jr, H.G. Koenig, D. Mark, K.L. Lee, Music, imagery, touch, and prayer as adjuncts to interventional cardiac care: the Monitoring and Actualisation of Noetic Trainings (MANTRA) II randomised study Lancet 366 (2005):211-217. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 H. Benson, J.A. Dusek, et al., Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP) in cardiac bypass patients: a multicenter randomized trial of uncertainty and certainty of receiving intercessory prayer American Heart Journal 151(4) (April 2006): 762-764. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ William Saletan, The Deity in the Data: What the latest prayer study tells us about God Slate, April 6, 2006. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 6:16 Retrieved January 1, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aviles J.M., S.E. Whelan, D.A. Hernke, B.A. Williams, K.E. Kenny, W.M. O'Fallon, and S.L. Kopecky. Intercessory prayer and cardiovascular disease progression in a coronary care unit population: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2001 76: 1192-1198.

- Benson H., J.A. Dusek, et al. Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP) in cardiac bypass patients: a multicenter randomized trial of uncertainty and certainty of receiving intercessory prayer. American Heart Journal (April 2006) 151(4): 762-764.

- Byrd R.C. Positive therapeutic effects of intercessory prayer in a coronary care unit population. South Med J (1988) 81: 826-829.

- Galton Francis. Statistical inquiries into the efficacy of prayer. Fortnightly Review (1872) 68:125-135.

- Greenberg, Moshe. Biblical Prose Prayer: As a Window to the Popular Religion of Ancient Israel. (The Taubman Lectures in Jewish Studies. Sixth Series) Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983. ISBN 0520050118

- Harris W.S., M. Gowda, J.W. Kolb, C.P. Strychacz, J.L. Vacek, P.G. Jones, A. Forker, J.H. O'Keefe, B.D. McCallister. A randomized, controlled trial of the effects of remote, intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients admitted to the coronary care unit. Arch Intern Med (1999) 159: 2273-2278.

- Krucoff, M.W., S.W. Crater, D. Gallup, J.C. Blankenship, M. Cuffe, M. Guarneri, R.A. Krieger, V.R. Kshettry, K. Morris, M. Oz, A. Pichard, M.H. Sketch, Jr, H.G. Koenig, D. Mark, K.L. Lee. Music, imagery, touch, and prayer as adjuncts to interventional cardiac care: the Monitoring and Actualisation of Noetic Trainings (MANTRA) II randomised study. Lancet (2005) 366:211-217.

- Leibovici, L. Effects of remote, retroactive intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients with bloodstream infection: randomized controlled trial. BMJ (2001) 323:1450-1451.

- O'Laoire, S. An experimental study of the effects of distant, intercessory prayer on self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. Altern Ther Health Med (1997) 3:38-53.

- Pritchard, James B. (ed.). The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0691147260

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2022.

- Prayer Crosswalk.com.

- Prayers and Devotions United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

- Prayer Desiring God.

- Christian Prayer and Eastern Meditation JourneyOnline.org.

- 5 Types of Prayer in Different World Religions The Yeshiva World.

- Essential Prayers of World Religions BeliefNet.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.