Saint Dominic

| Saint Dominic | |

|---|---|

Saint Dominic | |

| Confessor | |

| Born | 1170 in Calaruega, Province of Burgos, Kingdom of Castile (Spain) |

| Died | August 6, 1221 in Bologna,Italy |

| Canonized | 1234 |

| Major shrine | San Domenico, Bologna |

| Feast | August 8 August 4 (Traditional Roman Catholics) |

| Attributes | Confessor; Chaplet, dog, star |

| Patronage | Astronomers, Dominican Republic, falsely accused people, scientists |

Saint Dominic (Spanish: Domingo), often called Dominic de Guzmán (1170 – August 6, 1221), was the founder of the Friars Preachers, popularly called the Dominicans or Order of Preachers (OP), which became famous for its role in the Inquisition.

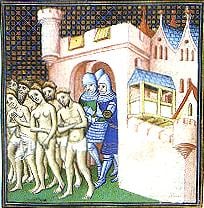

Witnessing the success of the Cathar movement in southern France, Dominic urged those in charge of combating the "heresy" to practice a more exemplary standard of spiritual life. He eventually took this mission on himself, living an ascetic lifestyle and debating the Cathars in public disputes. He also supported the military campaigns against the Cathars during the Albigensian Crusade.

At Dominic's request, the Order of Preachers was formally established by Pope Honorius III in 1216, to preach in conquered Cathar territory and to combat the spread of heresy. Dominic's role, if any, in the Inquisition is a subject of debate. His friend and protector, the future Pope Gregory IX, initiated the papal Inquisition under Dominican supervision a few years after Dominic's death, and any personal involvement by Dominic himself would have been at the local level in southern France.

The Dominican Order would go on to play a major role in the Catholic intellectual tradition, in which it is still active today. Dominic is the patron saint of astronomers, the falsely accused, scientists, and the Dominican Republic. His feast day in the Catholic Church is August 8.

Biography

Birth and education

Born in Caleruega, halfway between Osma and Aranda in Old Castile, Spain, Dominic was named after Saint Dominic of Silos, the patron saint of hopeful mothers. The Benedictine Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos lay a few miles north of his birthplace.

In the earliest sources, Dominic's parents are not named, but the story is told that before his birth, his mother dreamed that a dog leaped from her womb carrying a torch in its mouth, and "seemed to set the earth on fire." This reference, however is thought by critical scholars to be a later interpolation, as the Latin name of his order, Dominicanus is a pun on "Domini Canus," the "Lord's hound." Dominic was reportedly brought up by his parents and a maternal uncle, who was an archbishop. A later source, still of the [thirteenth century]], gives the names of Dominic's mother and father as Juana de Aza and Felix. Dominic's father was reportedly an honored and wealthy man in his village, a claim which fits with the idea that his uncle was an archbishop.

Dominic was educated in the schools of Palencia, which later became a university. He reportedly devoted six years to the arts and four to theology. In 1191, when Spain was desolated by a famine, Dominic was just finishing his theological studies. He is said to have given away money, even selling his clothes, furniture, and valuable manuscripts, in order to relieve the distress of those affected. When his companions expressed astonishment that he should sell his books, Dominic replied: "Would you have me study off these dead skins, when men are dying of hunger?" However, in later years, Dominic emphasized the value of learning and insisted that the members of his order devote considerable energy to intellectual training.

Around 1194, Dominic became a Praemonstratensian priest in the canonry of Osma, following the monastic rule of Saint Augustine. On the accession of Don Diego de Acebo to the bishopric of Osma in 1201, Dominic became superior of the chapter with the title of prior.

Encounter with heresy

In 1203 or 1204, he accompanied Bishop Diego on a diplomatic mission to Denmark on behalf of King Alfonso VIII of Castile, in order to secure a Danish bride for crown prince Ferdinand. The mission made its way to Denmark via the south of France, and when they crossed the Pyrenees, Dominic and Diego encountered the Cathars, also known as the Albigensians. The country was filled with these preachers of unfamiliar doctrines. Dominic was shocked not only by what he considered to be the heretical teachings of the Cathars, but also at their lack of respect for the Catholic Church and the pope, not to mention Bishop Diego and Dominic himself. The experiences of this journey kindled in Dominic a passion to work for extermination of the "heresy" which had infected a large portion of the population of southern France. He was also deeply impressed by the fact that the Cathar preachers were not ignorant fanatics, but well-trained and cultured men, whose communities seemed to be motivated by a desire for knowledge and for righteousness. Dominic perceived that only well educated preachers capable of advancing reasonable arguments could effectively combat the Cathar heresy.

Traveling again to Denmark about a year later and finding that the prince's intended bride had died, Diego and Dominic returned by way of Rome. The purpose of this trip was to enable Diego to resign his bishopric so that he could devote himself to the conversion of unbelievers in distant lands. Innocent III, however, refused to approve this project and instead sent the bishop and Dominic to Languedoc to join forces with the Cistercians, to whom he had entrusted the crusade against the Albigensians.

The scene that confronted them on their arrival in Languedoc was by no means an encouraging one. The Cistercians, on account of their worldly manner of living, had made little or no headway against the Albigensians. They had entered upon their work with considerable pomp, attended by a brilliant retinue and well provided with the comforts of life. The Cathar leaders, themselves, on the other hand, adhered to a strict asceticism which commanded the respect and admiration of their followers. Diego and Dominic quickly saw that the failure of the Cistercian mission was due to the monks' indulgent habits, and prevailed upon them to adopt a more austere manner of life. This change apparently did increase the effectiveness of efforts to convert some of the Cathars to accept Catholicism.

Theological disputations also played a prominent part in these efforts. Dominic and Bishop Diego engaged the Cathars whenever the opportunity offered itself. Catholic sources portray Dominic as an invincible champion in this regard, although his efforts did little to stem the tide of Cathar influence. Dominic remained a number of years in the south of France engaged in this work. In late 1206 or early 1207, with the help of Bishop Foulques of Toulouse and the financial support of the wealthy patrons Guillaume and Raymonde Claret, Diego and Dominic were able to set up a monastic community at Prouille near Carcassonne, intended largely as a refuge for women who had previously lived in Cathar religious houses. Soon afterward, Diego was commanded by the pope to return to his diocese. In 1207, Dominic took part in the last large scale public debate between Cathars and Catholics, at Pamiers.

By this time Innocent III had grown impatient with mere words to combat the Cathars and urged the French nobles to more direct action. When the powerful count Raymond VI of Toulouse refused to comply, he was excommunicated. The pope called upon the King Philippe II to act against those nobles who permitted Catharism, but Philippe also declined to act. Count Raymond met with the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, in January 1208. The meeting went poorly, and Castelnau was murdered the following day. The pope reacted to the murder by issuing a bull declaring a crusade against Languedoc, offering the land of the heretics as a reward for those who participated. This offer of land drew the northern French nobility into conflict with the nobles of the south.

The early stages of the Albigensian Crusade under Simon de Montfort led to the temporary subjugation of the Cathars and provided new opportunities for Dominic to evangelize in the conquered Cathar lands. In the aftermath of the battles, Dominic reportedly intervened on behalf of non-combatants among the Cathar population, appealing to Montfort's forces to spare the lives of the innocent, though not always successfully.

Foundation of the Dominicans

Later in 1208, Dominic reportedly encountered papal legates returning in pomp to Rome. To this group he administered a famous rebuke: "It is not by the display of power and pomp, cavalcades of retainers… or by gorgeous apparel, that the heretics win proselytes. It is by zealous preaching, by apostolic humility, by austerity, and—by seeming, it is true—but by seeming holiness. Zeal must be met by zeal, humility by humility, false sanctity by real sanctity, preaching falsehood by preaching truth."

Determined to create a movement to put this principle into practice, Dominic gathered a small group of priests formed around himself, but they soon left him, discouraged by the rigors of his ascetic lifestyle and the lack of progress in converting the Cathars. Eventually, he found a number of men who remained faithful to his vision.

In September 1209, Dominic met personally with the anti-Cathar crusader Simon de Montfort and formed with him an intimate friendship, which was to last until Simon's death in battle against Cathar forces at Toulouse in 1218. Dominic followed Simon's forces on their campaigns and preached to the conquered Cathars. Although the papal Inquisition would not begin until after his death it is certainly possible that Dominic participated in inquisitions during this time under the supervision of local bishops as a theologian passing judgment on the orthodoxy of accused Cathar leaders. He stood with Montfort at the siege of Lavaur in 1211, and at the capture of the stronghold of La Penne d'Ajen in 1212. In September, 1213, Dominic gave advice to Montfort preceding the battle of Muret. Simon regarded his victory over the Cathars there as altogether miraculous, and attributed it to the prayers of Dominic.

Nevertheless, Dominic was convinced that, while military means were a necessary part of the struggle against Catharism, the ultimate victory must be spiritual and intellectual. In 1215, he established himself, with six followers, in a castle provided by Pierre Seila, a wealthy resident of Toulouse. There, he subjected himself and his companions to strict monastic rules of prayer and penance. Bishop Foulques gave them written authority to preach throughout the territory of Toulouse. Thus the foundations for the order of Preaching Friars began to assume definite shape. Dominic reportedly dreamed of seven stars enlightening the world, which represented himself and his six friends.

In the same year, while the Fourth Lateran Council was meeting in Rome, Dominic and Bishop Foulques went to the holy city to secure papal approval for the formation of a new monastic order devoted specifically to preaching. This was refused, but Dominic returned to Rome a year later and was granted written authority by the new pope, Honorius III, to create the Order of Preachers (Ordo Praedicatorum, or "O.P.").

Later life

Dominic now established his headquarters at Rome, although he traveled extensively to maintain contact with his growing brotherhood of monks. At Rome he made important friends, including Cardinal Ugolino de' Conti, the future Pope Gregory IX.

Throughout his life, Dominic is said to have zealously practiced rigorous self-denial. He wore a hairshirt and an iron chain around his loins, which he reportedly never laid aside, even in sleep. He abstained from meat and observed various fasts and periods of silence. He is said to have selected for himself the most humble accommodations and the simplest clothes, never allowing himself even the basic luxury of a bed. When traveling, he often took off his shoes and trudged on his way barefooted.

When visiting Bologna in January 1218, Dominic saw immediately that this university city, situated between Rome and souther France, would be most convenient as his center of activity for his growing order. Soon Reginald of Orléans established a religious community at the Mascarella church, which was later moved to St Nicholas of the Vineyards. Dominic settled in this church, where he held the first two general chapters of the now widespread order.

At the close of the second general chapter Dominic set out for Venice to visit Cardinal Ugolino, to whom he was especially indebted for many substantial acts of kindness. He had scarcely returned to Bologna when a fatal illness attacked him. Death came at the age of 51, on August 6, 1221.

In a papal bull dated at Spoleto, July 13, 1234, Ugolino, now Gregory IX declared Dominic a saint and decreed that his cult should be obligatory throughout the Catholic Church.

Dominic's church in Bologna was later expanded and grew into the Basilica of Saint Dominic, consecrated by Pope Innocent IV in 1251. In 1267, Dominic's remains were moved to the exquisite shrine, made by Nicola Pisano and his workshop, Arnolfo di Cambio and with later additions by Niccolò dell'Arca and the young Michelangelo. At the back of this shrine, the head of Dominic is enshrined in a huge, golden reliquary, a masterpiece of the goldsmith Jacopo Roseto da Bologna (1383).

Legacy

Although Dominic was a zealous opponent of heresy and favored military means to suppress the Cathars, what part he had personally in the proceedings of the Inquisition has been disputed for many centuries. The historical sources from Dominic's own time period tell us nothing about his involvement in the Inquisition. It is more unlikely that he was involved in episcopal inquisitions under the guidance of local bishops in southern France. However, the papal Inquisition was initiated by Pope Gregory IX only after Dominic's death. Appreciating Dominic's intellectual and spiritual tradition, Gregory placed the administration of the Inquisition under the Dominican Order. Several early Dominicans, including some of Dominic's first followers, thus clearly did become important inquisitors.

The notion that Dominic himself had been an inquisitor first appears in the fourteenth century through the writings of a famous Dominican inquisitor, Bernard Gui, who portrayed Dominic as an enthusiastic participant. In the fifteenth century, Dominic would be depicted in Catholic art as presiding at an auto da fé, the public condemnation of heretics during the Spanish Inquisition. Since the Catholic Church during this period had no interest in correcting the impression that Dominic himself was an inquisitor, it was at pains later on, once the Inquisition had been discredited, to correct the record.

Some histories of the rosary claim this tradition, too, originated with Saint Dominic. One legend holds that the Virgin Mary appeared to Saint Dominic in the church of Prouille, in 1208, and gave the rosary to him. However, other sources dispute this attribution and suggest that its roots were in the preaching of Alan de Rupe between 1470-1475. However, for centuries, Dominicans have been instrumental in spreading the rosary and emphasizing the Catholic belief in its power.

Dominic's greatest legacy, however, is the Dominican Order itself. Beyond the infamous role it played in investigating and prosecuting heresy during the Inquisition, the Dominicans were also noted (though not as much as the Franciscans) for attempting to reform the Catholic Church by opposing the wealth and luxury of some of its priests and bishops. Famed for its intellectual tradition, the order has produced many leading Catholic theologians and philosophers. Among hundreds of famous Dominicans are St. Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, St. Catherine of Siena, and Girolamo Savonarola. Four Dominican cardinals have become popes.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alemany, J.S. The Life of St. Dominic and a Sketch of the Dominican Order. Kessinger Publishing, 2007. ISBN 9780548105597.

- Bedouelle, Guy. Saint Dominic: The Grace of the Word. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1987. ISBN 9780898701401.

- Hinnebusch, William A. The History of the Dominican Order. Alba House, 1966. ISBN 9780818902666.

- Oldenbourg, Zoe. Massacre at Montsegur: A History of the Albigensian Crusade. Marboro Books, 1988. ISBN 978-0880294775.

- Tugwell, Simon. Saint Dominic. Strasbourg: Éditions du Signe, 1995. ISBN 9782877182782.

- Zagano, Phyllis, and Thomas McGonigle. The Dominican Tradition. Liturgical Press, 2006. ISBN 9780814619117.

- This article incorporates text from the 1913 Catholic Enyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Saint Dominic. www.newadvent.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.