Albigensian Crusade

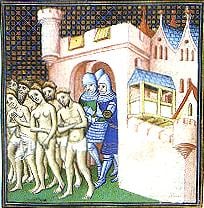

The Albigensian Crusade, or Cathar Crusade (1209–1229), was a twenty year military campaign initiated by the Roman Catholic Church to eliminate the heresy of the Cathars of Languedoc.

When Innocent III's diplomatic and evangelical attempts to roll back Catharism met with limited success, he declared a crusade against Languedoc, offering lands belonging to the schismatics to any French nobleman willing to take up arms to defeat them. The violence led to France's acquisition of lands with closer cultural and linguistic ties to Catalonia than France. An estimated one million people died during the crusade.[1]

The Albigensian Crusade also had a role in the creation and institutionalization of both the Medieval Inquisition and the Dominican Order, which was created to combat this heresy. Although they succeeded in virtually wiping out the Cathar heresy, the crusade and the Inquisition that followed it represent a major blemish on the Catholic Church's human rights record.

Origin

The Cathars were especially numerous in what is now western Mediterranean France, then part of the Crown of Aragon. They were also called Albigensians; this is either because of the movement's presence in and around the city of Albi, or because of the 1176[2] Church Council held near Albi, which declared the Cathar doctrine heretical. Political control in Languedoc was divided among many local lords and town councils. Before the crusade, there was little fighting in the area, which had a fairly sophisticated polity.

The Roman Catholic Church had long dealt vigorously with strands of Christianity that it considered heretical. However, before the twelfth century, such groups in medieval Europe were organized in small numbers, around wayward preachers or small localized sects. The Cathars of Languedoc represented an alarmingly popular mass movement,[3] a phenomenon that the Church had not countenanced for centuries. In the twelfth century, much of what is now Southern France was converting to Catharism, and the belief was spreading to other areas as well. The Cathars, along with other religious sects of the period such as the Waldensians, appeared in the cities and towns of newly urbanized areas. Although Cathar ideas had not originated in Languedoc, it was there that their theology found its most spectacular success.

On becoming Pope in 1198, Innocent III resolved to deal with the Cathars. He first tried peaceful conversion, but the preachers sent out to return the schismatics to the Roman communion met with little success.[4] Even Saint Dominic succeeded in converting only a handful. The Cathar leadership was protected by powerful nobles,[5] and also by some bishops, who resented papal authority in their sees. In 1204, the Pope suspended the authority of some of those bishops, appointing papal legates to act in his name.[6] In 1206, he sought support for wider action against the Cathars from the nobles of Languedoc. Noblemen who supported Catharism were excommunicated.

The powerful count Raymond VI of Toulouse refused to assist and was excommunicated in May 1207. The pope called upon the French king, Philippe II, to act against those nobles who permitted Catharism, but Philippe declined to act. Count Raymond met with the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, in January 1208,[7] and after an angry meeting, Castelnau was murdered the following day.[8] The pope reacted to the murder by issuing a bull declaring a crusade against Languedoc, offering the land of the heretics as a reward for those who participated. This offer of land drew the northern French nobility into conflict with the nobles of the south.

Military campaigns

The military campaigns of the Albigensian Crusade can be divided into several periods. The first, from 1209 to 1215, was a series of great successes for the crusaders in Languedoc. However, in the next phase, between 1215 and 1225, the captured lands were largely lost in a series of revolts and military reverses. The situation turned again following the intervention of the French king, Louis VIII, who joined the crusade in 1226. Although he died in November of that year, the struggle continued under King Louis IX. The area was reconquered by 1229, and the leading nobles made peace. After 1233, the Inquisition, under the leadership of the Domincan Order, was central to crushing what remained of Catharism. Resistance and occasional revolts continued, but Catharism's days were numbered. Military action ceased in 1255.

In the end, the Albigensian Crusade is estimated to have killed 1 million people, not only Cathars but a significant portion of the general population of southern France.

Initial success 1209 to 1215

By mid 1209, after the murder of Innocent's legate and the issuing of the pope's bull declaring the crusade against the Cathars, around 10,000 crusaders had gathered in Lyon, before marching south.[9] In June, Raymond of Toulouse, recognizing the disaster at hand, finally promised to act against the Cathars, and his excommunication was lifted.[10] The crusaders turned towards Montpellier and the lands of Raymond-Roger de Trencavel, aiming for the Cathar communities around Albi and Carcassonne. Like Raymond of Toulouse, Raymond-Roger sought an accommodation with the crusaders, but he was refused a meeting and raced back to Carcassonne to prepare his defenses.[11]

In July, the crusaders captured the small village of Servian and headed for Béziers, arriving on July 21. They surrounded the city, called the Catholics within to come out, and demanded that the Cathars surrender.[12] Both groups refused to comply. The city fell the following day when an abortive sortie by the defenders was pursued back through the open city gates.[13] The entire population, regardless of faith, was slaughtered, and the city was burned to the ground. Contemporary sources give estimates of the number of dead ranging between 7,000 to 20,000. The latter figure appears in the papal legate Arnaud-Amaury's own report to the pope, in which he admits that no one was spared.

According to the Cistercian writer, Caesar of Heisterbach, one of the leaders of the crusader army, Arnaud-Amaury, when asked by a crusader how to distinguish the Cathars from the Catholics, answered: "Caedite eos! Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius"—"Kill them [all]! Surely the Lord discerns which [ones] are his." On the other hand, the legate's own statement, in a letter to the Pope in August 1209 (col.139), states:

While discussions were still going on with the barons about the release of those in the city who were deemed to be Catholics, the servants and other persons, of low degree and unarmed, attacked the city without waiting for orders from their leaders. To our amazement, crying "to arms, to arms!" within the space of two or three hours they crossed the ditches and the walls and Béziers was taken. Our men spared no one, irrespective of rank, sex, or age, and put to the sword almost 20,000 people. After this great slaughter the whole city was despoiled and burnt.

The news of the disaster at Béziers quickly spread and afterwards many settlements surrendered without a fight.

The next major target was Carcassonne. The city was well fortified, but vulnerable, and overflowing with refugees.[14] The crusaders arrived on August 1, 1209. The siege did not last long. By August 7, the crusaders had cut the city's water supply. Raymond-Roger sought negotiations but was taken prisoner while under truce, and Carcasonne surrendered on August 15.[15] Its people were not killed, but were forced to leave the town—naked, according to Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay, "in their shifts and breeches" according to another source. Simon de Montfort now took charge of the crusader army,[16] and was granted control of the area encompassing Carcassonne, Albi, and Béziers. After the fall of Carcassonne, other towns surrendered without a fight. Albi, Castelnaudary, Castres, Fanjeaux, Limoux, Lombers and Montréal all fell quickly during the autumn.[17] However, some of the towns that had surrendered later revolted.

The next battle centered around Lastours and the adjacent castle of Cabaret. Attacked in December 1209, Pierre-Roger de Cabaret repulsed the assault.[18] Fighting largely halted over the winter, but fresh crusaders arrived. In March 1210, Bram was captured after a short siege. In June, the well-fortified city of Minerve was besieged. It withstood a heavy bombardment, but in late June the main well was destroyed, and on July 22, the city surrendered. The Cathars of the city were given the opportunity to return to Catholicism. Most did so, but the 140 who refused were burned at the stake. In August, the crusade proceeded to the stronghold of Termes. Despite counter-attacks by the forces of Pierre-Roger de Cabaret, the siege held solid, and in December, the town fell.[19] It was the last action of the year.

By the time operations resumed in 1211, the harsh actions of the crusaders had alienated several important lords, including Raymond de Toulouse, who had been excommunicated again. The crusaders returned in force to Lastours in March, and Pierre-Roger de Cabaret soon agreed to surrender. In May, the castle of Lord Aimery of Montréal, south of Carcassonne, was retaken; he and his senior knights were hanged, and several hundred Cathars were burned.[20] Cassès and Montferrand both fell easily in early June, and the crusaders headed for Toulouse. The town was besieged, but for once the attackers were short of supplies and men, and so Simon de Montfort withdrew before the end of the month. Emboldened, Raymond de Toulouse led a force to attack Montfort's forces at Castelnaudary in September. Castelnaudary fell and the forces of Raymond went on to liberate over 30 towns before the campaign ground to a halt at Lastours in the autumn. The following year much, of the province of Toulouse was recaptured by Catholic forces.

In 1213, forces led by King Peter II of Aragon, came to the aid of Toulouse against the crusaders.[21] The force besieged Muret, but in September a sortie from the castle led to the death of King Peter, and his army fled. It was a serious blow for the resistance, and in 1214, the situation became worse: Raymond was forced to flee to England, and his lands were given by the Pope Innocent II to the victorious King Philippe II, who had by then joined the conflict. In November, the always active Simon de Montfort entered Périgord and easily captured the castles of Domme and Montfort. He also occupied Castlenaud and destroyed the fortifications of Beynac. In 1215, Castelnaud was recaptured by Montfort, and the crusaders entered Toulouse. Toulouse itself was then gifted to Montfort.[22] In April 1216, he ceded his lands to Philippe.

Revolts and reverses 1216 to 1225

The resistance was far from finished, however. Raymond, together with his son, returned to the region in April, 1216 and soon raised a substantial force from disaffected towns. Beaucaire was besieged in May and fell after a three month siege. The efforts of Montfort to relieve the town were repulsed. Montfort then had to put down an uprising in Toulouse before heading west to capture Bigorre, but he was repulsed at Lourdes in December 1216. In September 1217, while Montfort was occupied in the Foix region, Raymond re-took Toulouse. Montfort hurried back, but his forces were insufficient to recapture the town before campaigning halted. Montfort renewed the siege in the spring of 1218. He was killed during this fighting in June.

Innocent III had died in July 1216. With his champion Montfort now dead, the crusade was left in temporary disarray. The command passed to the more cautious Philippe II, whose interests in putting down heresy lacked the zeal of Montfort. The crusaders took Belcaire and besieged Marmande in late 1218 under Amaury de Montfort, son of the late Simon. Marmande fell on June 3, 1219, but attempts to retake the major prize of Toulouse failed, and a number of Montfort strongholds also fell. In 1220, Castelnaudary was retaken from Montfort's forces. Amaury de Montfort besieged the town in July 1220, but it withstood an eight-month trial.

In 1221, the success of Raymond and his son continued: Montréal and Fanjeaux were re-taken, and many Catholics were forced to flee. In 1222, Raymond died and was succeeded by his son, also named Raymond. In 1223, Philippe II died and was succeeded by Louis VIII. In 1224, Amaury de Montfort abandoned Carcassonne. The son of Raymond-Roger de Trencavel returned from exile to reclaim the area. Montfort offered his claim to the lands of Languedoc to Louis VIII, who accepted.

French royal intervention

In November 1225, the young Raymond, like his father, was excommunicated. Louis VIII himself headed the new crusade into the area in June 1226. Fortified towns and castles surrendered without resistance. However, Avignon, nominally under the rule of the German emperor, did resist, and it took a three-month siege to finally force its surrender that September.

Louis VIII died in November and was succeeded by the child king Louis IX. But Queen regent Blanche of Castile allowed the crusade to continue under Humbert de Beaujeu. Labécède fell in 1227, and Vareilles and Toulouse in 1228. However, Queen Blanche offered Raymond a treaty: Recognizing him as ruler of Toulouse in exchange for his fighting against Cathars, returning all Church property, turning over his castles, and destroying the defenses of Toulouse. Raymond agreed and signed the treaty at Meaux in April 1229. He was then seized, whipped, and briefly imprisoned.

Inquisition and final military actions

The Languedoc now was firmly under the control of the King of France, and the policy of dealing with the Cathars primarily through military means shifted toward wiping them out through persuasion and torture. The Inquisition was established in Toulouse in November 1229. Under Pope Gregory IX, the Inquisition, under the leadership of the new Dominican Order, was given great power to suppress the heresy.

A campaign started in 1233, burning vehement and relapsed Cathars wherever they were found, even exhuming some bodies for burning. Many still resisted, taking refuge in fortresses at Fenouillèdes and Montségur, or inciting small uprisings. In 1235, the Inquisition was forced out of Albi, Narbonne, and Toulouse. Raymond-Roger de Trencavel led a military campaign in 1240. He was defeated at Carcassonne in October, then besieged at Montréal. He soon surrendered and was exiled in Aragon. In 1242, Raymond of Toulouse attempted to revolt in conjunction with an English invasion, but the English were quickly repulsed and his support evaporated. He was subsequently pardoned by the French king.

The Cathar strongholds fell one by one. Montségur withstood a nine-month siege before being taken in March 1244. The final holdout, a small, isolated, overlooked fort at Quéribus, quickly fell in August 1255. The last known Cathar burning occurred in 1321.

Notes

- ↑ Time Magazine, Massacre of the Pure. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ↑ Johann Lorenz Mosheim, Mosheim's Institutes of Ecclesiastical History, Ancient and Modern (W. Tegg, 1867), p. 385.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), §5.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 6.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 8-9.

- ↑ Sibly (2003), p. VII.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 55-58.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 59-60.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 84.

- ↑ Sibly (2003), p. XIII.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 88.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 89.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 90-91.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 92-93.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 98.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 101.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 108-113.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 114.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 169-189.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 215.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 367-446.

- ↑ Sibly (1998), p. 554-559, 573.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arnold, John H. Inquisition and Power. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0812236187.

- Duvernoy, Jean (ed.). Guillaume de Puylaurens, Chronique 1145-1275: Chronica magistri Guillelmi de Podio Laurentii. Paris: CNRS, 1976. ISBN 2910352064.

- Martin, Sean. The Cathars: The Most Successful Heresy of the Middle Ages. Thunder's Mouth Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1560256748.

- Oldenbourg, Zoe. Massacre at Montsegur: A History of the Albigensian Crusade. Marboro Books, 1988. ISBN 978-0880294775.

- Sibly, W.A. and M. D. Sibly (trans.). The History of the Albigensian Crusade: Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay's Historia Albigensis. Woodbridge: Boydell, 1998. ISBN 0851158072.

- Sibly, W.A. and M.D. Sibly (trans.). The Chronicle of William of Puylaurens: The Albigensian Crusade and its Aftermath. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2003. ISBN 0851159257.

- Weis, Rene J.A. The Yellow Cross: The Story of the Last Cathars. Knopf, 2001. ISBN 978-0375404900.

External links

All links retrieved June 17, 2023.

- Albigensian Crusade. xenophongroup.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.