The Cathari (also known as Cathars, Albigensians, or Catharism) were followers of a controversial religious sect that flourished in the Languedoc region of France between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries before they were eradicated by the Albigensian Crusade and the subsequent Roman Catholic Inquisition. The Cathari adopted gnostic, dualist (and perhaps Manichaean beliefs)[1] in their theology, espousing a stark distinction between the physical world (seen as evil) and the spiritual world (seen as good). They also embraced the doctrine of reincarnation, which went against the mainstream Christian teaching of resurrection of the dead.[2] As a result of these heterodox beliefs, the Roman Catholic Church regarded the sect as heretical, and faced with the rapid spread of the movement across the Languedoc regions, as well as the failure of peaceful attempts at conversion, the Vatican launched the Albigensian Crusade to crush the movement.

The heavy-handed approach of the Vatican to the Cathari resulted in much violence and bloodshed in the name of Christian religious orthodoxy. The history of the Cathari, thus, provides an important reminder that the Crusades not only caused deep historical divisions between Muslims and Christians, but also unleashed terror against alleged internal enemies within Christendom, leading to unspeakable horror and abuse.

Name

The origins of the title, "Cathar," are obscure and shrouded in mystery. The most popular theory is that the word Cathar most likely originated from Greek καθαροί (Katharoi), meaning "pure ones," a term related to the word Katharsis or Catharsis, meaning "purification." Another theory is that the term is abusive, referring to the bizarre and obscene ritual "Kiss of the Cat," which the Cathars were falsely rumored to practice.[3] The first recorded use of the word is by religious authority Eckbert von Schönau, who wrote of heretics from Cologne in 1181: Hos nostra Germania catharos appellat ("In Germany we call these people Cathars"). It seems that the Cathars had no official name for their movement, referring to themselves only as Bons Hommes et Bonnes Femmes ("Good Men and Good Women").

By the end of the twelfth century, the Cathars were also called Albigensians, which referred to the town of Albi (the ancient Albiga) northeast of Toulouse. However, this geographical reference is misleading because the movement had no center and is known to have flourished in areas that are now parts of Italy (for example, Lombardy and Tuscany), Germany (particularly the Rhineland), Northern France and Belgium, Aragon and Catalonia in today's Spain, as well as the Languedoc.

History

Reconstructing the history of the Cathars is problematic due, firstly, to the paucity of extant historical sources available to scholars about the sect, and, secondly, to the fact that most descriptions of the group come from the criticisms of its enemies. Much of the existing knowledge of the Cathars is derived from their opponents, the writings of the Cathars having been destroyed because of the doctrinal threat they posed to Christian theology. For this reason, it is likely, as with most heretical movements of the period, that modern scholars have only a partial view of their beliefs. Conclusions about Catharism continue to be fiercely debated with commentators regularly accusing others of speculation, distortion, and bias. There are a few texts from the Cathars themselves that were preserved by their opponents (the Rituel Cathare de Lyon, the Nouveau Testament en Provencal) that provide a glimpse of the inner working of their faith, but these still leave many questions unanswered. One large text that has survived, The Book of Two Principles, outlines dualistic theology from the point of view of some of the Albanenses Cathars.

Origins

It seems that the origin of Cathari beliefs derives from several sources, which fall outside of the region. The Cathars' beliefs are thought to have come originally from Eastern Europe and the Byzantine Empire by way of trade routes. This sect had its roots in the Paulician movement in Armenia and was also influenced by the Bogomiles with whom the Paulicians eventually merged. The name of Bulgarians (Bougres) was also applied to the group, and they maintained an association with the similar Christian movement the Bogomils ("Friends of God") of Thrace. Their doctrines have numerous resemblances to those of the Bogomils and the earlier Paulicians as well as the Manicheans and the Christian Gnostics of the first few centuries C.E.

It is now generally agreed by most scholars that Catharism did not emerge until at least 1143, when the first confirmed report of a group espousing similar beliefs is reported being active at Cologne by the cleric Eberwin of Steinfeld.[4]

Although there are certainly similarities in theology and practice between Gnostic and dualist groups of Late Antiquity (such as the Marcionites, Manichaeans, and so on) and the Cathars, there was not a direct link between the two; Manichaeanism died out in the West by the seventh century, and the Cathars were largely homegrown, springing up in the Rhineland cities (particularly Cologne) in the mid-twelfth century, northern France around the same time, and particularly southern France—the Languedoc—and the northern Italian cities in the late twelfth century. In the Languedoc and northern Italy, the Cathars would enjoy their greatest popularity, surviving in the Languedoc, in much reduced form, up to around 1310 and in the Italian cities until around the 1260s.[5]

Suppression

In 1147, Pope Eugene III sent a legate to the affected district in order to preclude the progress of the Cathars. The few isolated successes of Bernard of Clairvaux could not obscure the poor results of this mission, which clearly showed the power of the sect in the Languedoc at that period. The missions of Cardinal Peter of St. Chrysogonus to Toulouse and the Toulousain in 1178, and of Henry, cardinal-bishop of Albano, in 1180–1181, obtained only momentary successes. Henry of Albano's armed expedition, which took the stronghold at Lavaur, did not extinguish the movement.

Decisions of Catholic Church councils against the Cathars at this period—in particular, those of the Council of Tours (1163) and of the Third Council of the Lateran (1179)—had scarcely more effect. When Pope Innocent III came to power in 1198, he was resolved to deal with the Cathars.

At first, Innocent tried pacific conversion, and sent a number of legates into the affected regions. They had to contend not only with the Cathars, the nobles who protected them, and the people who venerated them, but also with many of the bishops of the region, who resented the considerable authority that the Pope had conferred upon the legates. In 1204, Innocent III suspended the authority of a number of bishops in the south of France; in 1205, he appointed a new and vigorous bishop of Toulouse, the former troubadour Foulques. In 1206, Diego of Osma and his canon, the future Saint Dominic, began a program of conversion in Languedoc; as part of this, Catholic-Cathar public debates were held at Verfeil, Servian, Pamiers, Montréal, and elsewhere.

Saint Dominic met and debated the Cathars in 1203, during his mission to the Languedoc. He concluded that only preachers who displayed real sanctity, humility, and asceticism could win over convinced Cathar believers. His conviction led eventually to the establishment of the Dominican Order in 1216. The order was to live up to the terms of his famous rebuke, "Zeal must be met by zeal, humility by humility, false sanctity by real sanctity, preaching falsehood by preaching truth."[6] However, even St. Dominic managed only few converts, and in the end told them, "In my country we have a saying, 'where blessing can accomplish nothing, blows may avail.'"[7]

Albigensian Crusade

In January 1208, the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau was sent to meet the ruler of the area, Count Raymond VI of Toulouse. Known for excommunicating noblemen who protected the Cathars, Pierre de Castelnau excommunicated Raymond as an abettor of heresy. Castelnau was immediately murdered near Saint Gilles Abbey on his way back to Rome by a knight in the service of Count Raymond. As soon as he heard of the murder, the Pope ordered the legates to preach a Crusade against the Cathars. Having failed in his effort to peacefully demonstrate the perceived errors of Catharism, the Pope then called a formal crusade, appointing a series of leaders to head the assault. Twenty years of war followed against the Cathars and their allies in the Languedoc: The Albigensian Crusade.

This war threw the whole of the nobility of the north of France against that of the south. The wide northern support for the Crusade was possibly inspired by a papal decree stating that all land owned by the Cathars and their defenders could be confiscated. As the Languedoc was teeming with Cathars and their sympathizers, this made the territory a target for French nobles looking to gain new lands. The barons of the north headed south to do battle.

Massacre

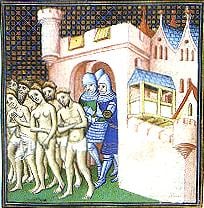

The crusader army came under the command, both spiritual and military, of the papal legate Arnaud-Amaury, Abbot of Cîteaux. In the first significant engagement of the war, the town of Béziers was besieged on July 22, 1209. The Roman Catholic inhabitants of the city were granted the freedom to leave unharmed, but most refused and opted to fight alongside the Cathars.

The Cathars attempted a sortie but were quickly defeated, and the pursuing knights chased them back through the open gates of the city. Arnaud, the Cistercian abbot-commander, is supposed to have been asked how to tell Cathar from Roman Catholic. His famous reply, recalled by a fellow Cistercian, was "Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius"—“Kill them all, the Lord will recognize His own.”[8] The doors of the church of St Mary Magdalene were broken down and the refugees dragged out and slaughtered. Reportedly, 7,000 people died there, including many women and children. Elsewhere in the town, many more thousands were mutilated and killed. Prisoners were blinded, dragged behind horses, and used for target practice. What remained of the city was razed by fire. Arnaud wrote to Pope Innocent III, "Today your Holiness, twenty thousand heretics were put to the sword, regardless of rank, age, or sex."[9] The permanent population of Béziers at that time was then probably no more than 15,000, but local refugees seeking shelter within the city walls could conceivably have increased the number to 20,000.

It was after the success of the siege of Carcassonne, which followed the massacre at Beziers, that Simon de Montfort was appointed to lead the Crusader army. Prominent opponents of the Crusaders were Raymond-Roger de Trencavel, viscount of Carcassonne, and his feudal overlord Peter II, the king of Aragon, who owned fiefdoms and had other vassals in the area. Peter died fighting against the crusade on September 12, 1213, at the Battle of Muret.

Treaty and persecution

The war ended in the Treaty of Paris (1229), by which the king of France dispossessed the house of Toulouse of the greater part of its fiefs, and that of the Trencavels (Viscounts of Béziers and Carcassonne) of the whole of their fiefs. The independence of the princes of the Languedoc was at an end. However, in spite of the wholesale massacre of Cathars during the war, Catharism was not yet extinguished.

In 1215, the bishops of the Catholic Church met at the Fourth Council of the Lateran under Pope Innocent. One of the key goals of the council was to combat the heresy of the Cathars by rejecting the Cathar's interpretation of the Doctrine of the Resurrection as meaning "reincarnation."

The Inquisition was established in 1229, to uproot the remaining Cathars. Operating in the south at Toulouse, Albi, Carcassonne and other towns during the whole of the thirteenth century, and a great part of the fourteenth, it finally succeeded in extirpating the movement. Cathars who refused to recant were sent to the galleys, hanged, or burned at the stake.[10]

From May 1243 to March 1244, the Cathar fortress of Montségur was besieged by the troops of the seneschal of Carcassonne and the archbishop of Narbonne. On March 16, 1244, a large and symbolically important massacre took place, where over 200 Cathar prefects were burned in an enormous fire at the prat des cramats near the foot of the castle. Moreover, the Church decreed chastisements against laymen suspected of sympathy with Cathars (Council of Narbonne, 1235).

Hunted by the Inquisition and deserted by the nobles of their districts, the Cathars became more and more scattered: Meeting surreptitiously in forests and mountain wilds. Later insurrections broke out under the leadership of Bernard of Foix, Aimery of Narbonne, and Bernard Délicieux (a Franciscan friar later prosecuted for his adherence to another heretical movement, that of the Spiritual Franciscans) at the beginning of the fourteenth century. However, by this time the Inquisition had grown very powerful. Consequently, many were summoned to appear before it. Precise indications of this are found in the registers of the Inquisitors, Bernard of Caux, Jean de St Pierre, Geoffroy d'Ablis, and others. The parfaits only rarely recanted, and hundreds were burned. Repentant lay believers were punished, but their lives were spared as long as they did not relapse. Having recanted, they were obliged to sew yellow crosses onto their outdoor clothing.[12]

Annihilation

After decades of not only severe persecution, but perhaps even more importantly the complete destruction of their writings, the sect was exhausted and could find no more adepts. By 1330, the records of the Inquisition contain very few proceedings against Cathars. The last known Cathar perfect in the Languedoc, Guillaume Bélibaste, was executed in 1321.

Other movements, such as the Waldensians and the pantheistic Brethren of the Free Spirit, which suffered persecution in the same area survived in remote districts in small numbers into the fourteenth and fifteenth century. Waldensian ideas were absorbed into early Protestant and Anabaptist sects, such as the Hussites, Lollards, and the Moravian Church (Herrnhutters of Germany). It is possible that Cathar ideas were too.

Beliefs

General

Cathars in general formed an anti-sacerdotal party in opposition to the Catholic Church, protesting what they perceived to be the moral, spiritual, and political corruption of the papacy. They claimed an Apostolic Connection to the early founders of Christianity and saw Rome as having betrayed and corrupted the original purity of the message.

The human condition

The Cathars claimed that there existed within humankind a spark of divine light. This light, or spirit, had fallen into captivity within a realm of corruption—identified with the physical body and world. This was a distinct feature of classical Gnosticism, of Manichaeism and of the theology of the Bogomils. This concept of the human condition within Catharism was most probably due to direct and indirect historical influences from these older (and sometimes also violently suppressed) Gnostic movements. According to the Cathars, the world had been created by a lesser deity, much like the figure known in classical Gnostic myth as the Demiurge. This creative force was identified with the Old Testament God and seen as the "False God," though he claimed for himself the title of the "one and only God." The Cathars identified this lesser deity, the Demiurge, with Satan. Thus, the Cathars believed that the Old Testament God of Jews and Christians was an impostor, and worship of this God was a corrupt abomination infused by the failings of the material realm. Spirit—the vital essence of humanity—was thus trapped in a polluted world created by a usurper God and ruled by his corrupt minions.

Eschatology

The goal of Cathar eschatology was liberation from the realm of limitation and corruption identified with material existence. The path to liberation first required an awakening to the intrinsic corruption of the medieval "consensus reality," including its ecclesiastical, dogmatic, and social structures. Once cognizant of the grim existential reality of human existence (the "prison" of matter), the path to spiritual liberation became obvious: matter's enslaving bonds must be broken. This was a step by step process, accomplished in different measures by each individual. The Cathars clearly accepted the idea of reincarnation. Those who were unable to achieve liberation during their current mortal journey would be reborn again on earth to continue the struggle for perfection. For the Cathars (like the Hindus and Buddhists), it should be understood that reincarnation was neither a necessary nor a desirable event, but a result of the fact that not all humans could break the enthralling chains of matter within a single lifetime.

Consolamentum

Cathar society was divided into two general categories, the Perfecti (Perfects, Parfaits) and the Credentes (Believers). The Perfecti were the core of the movement, though the actual number of Perfecti in Cathar society was always relatively small, numbering perhaps a few thousand at any one time. Regardless of their number, they represented the perpetuating heart of the Cathar tradition, the "true Christian Church," as they styled themselves.

An individual entered into the community of Perfecti through a ritual known as the consolamentum, a rite that was both sacramental and sacerdotal in nature: Sacramental in that it granted redemption and liberation from this world; sacerdotal in that those who had received this rite functioned in some ways as the Cathar clergy—though the idea of priesthood was explicitly rejected. The consolamentum was the baptism of the Holy Spirit, baptismal regeneration, absolution, and ordination all in one. Upon reception of the consolamentum, the new Perfectus surrendered his or her worldly goods to the community, vested himself in a simple black robe with cord belt, and undertook a life dedicated to following the example of Christ and His Apostles—an often peripatetic life devoted to purity, prayer, preaching, and charitable work. The demands of extreme asceticism fell only upon the Perfecti. Above all, the Perfecti were dedicated to enabling others find the road that led from the dark land ruled by the dark lord, to the realm of light, which they believed to be humankind's first source and ultimate end.

While the Perfecti vowed themselves to ascetic lives of simplicity, frugality and purity, Cathar credentes (believers) were not expected to adopt the same stringent lifestyle. They were, however, expected to refrain from eating meat and dairy products, from killing and from swearing oaths. Catharism was, above all, a populist religion and the numbers of those who considered themselves "believers" in the late twelfth century included a sizable portion of the population of Languedoc, counting among them many noble families and courts. These individuals often drank, ate meat, and led relatively normal lives within medieval society—in contrast to the Perfecti, whom they honored as exemplars. Though unable to embrace the life of chastity, the credentes looked toward an eventual time when this would be their calling and path.

Many credentes would also eventually receive the consolamentum as death drew near—performing the ritual of liberation at a moment when the heavy obligations of purity required of Perfecti would be temporally short. Some of those who received the sacrament of the consolamentum upon their death-beds may thereafter have shunned further food or drink in order to speed death. This has been termed the endura. It was claimed by Catharism's opponents that by such self-imposed starvation, the Cathars were committing suicide in order to escape this world.

Theology

The Cathari concept of Jesus might be called docetistic—theologically speaking it resembled Modalistic Monarchism in the West and Adoptionism in the East. Simply put, most Cathars believed that Jesus had been a manifestation of spirit unbounded by the limitations of matter—a sort of divine phantom and not a real human being. They embraced the Gospel of John as their most sacred text, and completely rejected the Old Testament—indeed, most of them proclaimed that the God of the Old Testament was, really, the devil. They proclaimed that there was a higher God—the True God—and Jesus was his messenger. These are views similar to those of Marcion.

They claimed that the God found in the Old Testament had nothing to do with the God of Love known to Cathars. The Old Testament God had created the world as a prison, and demanded from the "prisoners" fearful obedience and worship. This false god was a blind usurper who under the most false pretexts, tormented, and murdered those whom he called all too possessively "his children." The Cathari called the false god Rex Mundi, or The King of the World. The dogma of the Trinity and the sacrament of the Eucharist, among others, were rejected as abominations. Belief in metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls, resulted in the rejection of hell and purgatory, which were (and are) dogmas of the Roman Catholic Faith. For the Cathars, this world was the only hell—there was nothing worse to fear after death, save perhaps a return visit to this world.

Social relationships

From the theological underpinnings of the Cathar faith there came practical injunctions that were considered destabilizing to the mores of medieval society. For instance, Cathars rejected the giving of oaths as wrongful; an oath served to place one under the domination of the Demiurge and the world. To reject oaths in this manner was seen as anarchic in a society where illiteracy was wide-spread and almost all business transactions and pledges of allegiance were based on the giving of oaths.[13]

Sexual intercourse and reproduction propagated the slavery of spirit to flesh, hence procreation was considered undesirable. Informal relationships were considered preferable to marriage among Cathar credentes. Perfecti were supposed to observe complete celibacy, and separation from a partner would be necessary for those who would become Perfecti. For the credentes, however, sexual activity was not prohibited, but the creation of children was strongly discouraged, resulting in the charge by their opponents of sexual perversion. The common English insult "bugger" is said to derive from "bulgar," the notion that cathars followed the "Bulgarian heresy" whose teaching allegedly involved sodomy.[14]

Killing was abhorrent to the Cathars; so was the copulation that produced enslavement in matter. Consequently, abstention from all animal food except fish was enjoined of the Perfecti. (The Perfecti apparently avoided eating anything considered to be a by-product of sexual reproduction, including cheese, eggs, milk, and butter.) War and capital punishment were also condemned, an abnormality in the medieval age.

Such teachings, both in theological intent and practical consequence, brought upon the Cathars condemnation from civil and religious authorities as being enemies of Christian belief and of social order.

Later history

After the suppression of Catharism, the descendants of Cathars were, in some southern French towns, required to live apart from the main town and its defenses. They, thus, retained a certain Cathar identity, although they were Catholic in religion. This practice of separation, though increasingly uncommon, finally ended during the French Revolution.

Any use of the term "Cathar" to refer to people after the suppression of Catharism in the fourteenth century is a cultural or ancestral reference, and has no religious implication. Nevertheless, interest in the Cathars, their history, legacy, and beliefs continues. Furthermore, the Cathars have been depicted in popular books such as Holy Blood, Holy Grail as a group of elite nobility somehow connected to "secrets" about the true nature of the Christian faith, although there is no critical proof of such secrets being kept.

Pays Cathare

The term Pays Cathare (French meaning "Land of the Cathars" or "Cathar country") is used to highlight the Cathar heritage and history of the region where Catharism was traditionally strongest. This area is centered around towns such as Montsegur and Carcassonne; also the French département of the Aude uses the title Pays Cathare in tourist brochures.[15] These areas have ruins from the wars against the Cathars that are still visible today.

Some criticize the promotion of the identity of Pays Cathare as an exaggeration for tourist purposes.

Modern-day Cathars and Catharism

Some of the locals in the Pays Cathare region identify themselves as Cathars even today. They claim to be descended from the Cathars of the Middle Ages. It can be safely assumed that many local people have at least some ancestors who were Cathars. However, the delivering of the consolamentum, on which historical Catharism was based, required strict apostolical succession.

There are also people alive today who espouse the Cathar religion, either in the Pays Cathare or elsewhere.[16]

The Cathars in popular culture

It has been suggested in some modern fiction and non-fiction books that the Cathars could have been the protectors of the Holy Grail of Christian mythology.

- Zoe Oldenbourg's 1946 novel, Argile et Cendres (published in English as The World is Not Enough), is meticulously researched historical fiction set in a Cathar community.

- The novel, All Things Are Lights, by Robert Shea takes place during the extermination of the Cathars.

- The 2005 novel, The Color of a Dog Running Away by Richard Gwyn, contains a sequence that involves an encounter with Catharism.

- Babylonne, the protagonist of Catherine Jinks' novel, Pagan's Daughter, is a Cathar, as are many other main characters.

- The novel Labyrinth by Kate Mosse is based on the history of the Cathars.

- The novel Flicker by Theodore Roszak, where Cathars are at the heart of a mystery involving the use of secretive film techniques used to influence modern culture.

- Elizabeth Chadwick's 1993 novel, Daughters of the Grail, features the Cathars and their persecution by the Roman Catholic church.

Notes

- ↑ Steven Runciman, The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy (Cambridge University Press, 1982).

- ↑ Zoe Oldenbourg, Massacre at Montsegur: A History of the Albigensian Crusade (Marboro Books, 1988).

- ↑ Sara Lipton, Images of Intolerance: The Representation of Jews and Judaism in the Bible moralisée (University of California Press, 1999), p. 89.

- ↑ Walter Wakefield and Austin P. Evans (eds.), Heresies of the High Middle Ages.

- ↑ Emmanuel LeRoy Ladurie, Montaillou: the Enchanted Land of Error.

- ↑ Alfred Wesley Wishart, A Short History of Monks and Monasteries (BiblioBazaar, 2006), p. 142. ISBN 1426469454

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica, Saint Dominic. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ↑ Caesarius of Heisterbach, Caesarius Heiserbacencis monachi ordinis Cisterciensis, Dialogus miraculorum, edited by J. Strange (Cologne, 1851).

- ↑ J-P Migne (ed.), Patrologia Latinae cursus completus.

- ↑ Sean Martin, The Cathars (Pocket Essentials, 2005), p. 105-121.

- ↑ Sean Martin, The Cathars: The Most Successful Heresy of the Middle Ages (Thunder's Mouth Press, 2005), p. 109.

- ↑ Sean Martin, The Cathars: The Most Successful Heresy of the Middle Ages (Thunder's Mouth Press, 2005), p. 109.

- ↑ Morris Silver, Economic Structures of Antiquity (Greenwood Press, 1995), p. 10.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, Bugger. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ↑ Pays Cathare, Pays Cathare. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ↑ Cathar Net, FAQs. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arnold, John H. Inquisition and Power. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812236187.

- Berlioz, Jacques. Tuez-les tous Dieu reconnaîtra les siens. Le massacre de Béziers et la croisade des Albigeois vus par Césaire de Heisterbach. Loubatières, 1994.

- Eco, Umberto. Foucault's Pendulum. Ballantine, 1988. ISBN 978-0156032971.

- George, David. The Crusade of Innocents. BookSurge Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1419646348.

- Given, James. Inquisition and Medieval Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0801487590.

- Gui, Bernard. The Inquisitor's Guide: A Medieval Manual on Heretics. Translated by Janet Shirley. Ravenhall Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1905043095.

- Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy (trans.). Histories of the Cathars: Montaillou: The Promised Land of Error. Vintage Books, 1979. ISBN 978-0394729640.

- Lambert, Malcolm. The Cathars. Blackwell, 1998. ISBN 978-0631209591.

- Lansing, Carol. Power and Purity: Cathar Heresy in Medieval Italy. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0195149807.

- Markale, Jean. Montsegur and the Mystery of the Cathars. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-0892810901.

- Maris, Yves. CATHARS: Memories of an Initiate. 2006.

- Martin, Sean. The Cathars: The Most Successful Heresy of the Middle Ages. Thunder's Mouth Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1560256748.

- Moore, R.I. The Origins of European Dissent. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0802075666.

- Moore, R.I. The Formation of Persecuting Society. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992. ISBN 978-1405129640.

- Oldenbourg, Zoe. Massacre at Montsegur: A History of the Albigensian Crusade. Marboro Books, 1988. ISBN 978-0880294775.

- Pegg, Mark Gregory. The Corruption of Angels: The Great Inquisition of. Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0691123714.

- Peters, Edward (ed.). Heresy and Authority in Medieval Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0812277791.

- Rene, J.A. Weis. The Yellow Cross: The Story of the Last Cathars. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0375404900.

- Runciman, Steven. The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy. Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0521289269.

- Silver, Morris. Economic Structures of Antiquity. Greenwood Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0313293801.

- Wakefield, Walter, and Austin P. Evans. Heresies of the High Middle Ages. Columbia University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0231096324.

- Wishart, Alfred Wesley. A Short History of Monks and Monasteries. BiblioBazaar, 2006. ISBN 1426469454.

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2023.

- "Cathari" by N.A. Weber. The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1908.

- Cathar Texts and Rituals from Gnosis.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.