Cenobitic Monasticism

Cenobitic monasticism (also spelled coenobitic) is a form of monastic organization that stresses the community life of a monk as opposed to the solitary life of a hermit. The English words "cenobite" and "cenobitic" are derived, via Latin, from the Greek words κοινός and βίος (koinos and bios, meaning "common" and "life"). A group of monks living in a community is often referred to as a "cenobium." The older style of monasticism, to live as a hermit, is called eremitic; and a third form of monasticism, is the idiorrhythmic in which the he monk lives within a monastery but following his own schedule.

There are several cenobitic orders in the world's religions, which provide a sense of monastic community to like-minded practitioners. It is thought that the community life helps the monks to attain greater concentration through providing group support and role models. Typically, the life of the cenobitic monk involves the residence in a monastery and a daily schedule regulated by strict rules (such as the Rule of Saint Benedic in western Christianity or the Vinaya Pitaka in Theravada Buddhism).

Origins

Cenobitic monasticism exists in various religions, though Buddhist and Christian forms are the most prominent.

The organized version of Christian cenobitic monasticism is commonly thought to have started in Egypt in the fourth century C.E. Christian monks of previous centuries were usually hermits, especially in the Middle East; this continued to be very common until the decline of Syrian Christianity in the Late Middle Ages. This form of solitary living, however, did not suit everyone. Some monks found the eremitic style to be too lonely and difficult; and if one was not spiritually prepared, the life could lead to mental breakdowns.[1]

For this reason, organized monastic communities started to be created, so that monks could have more support in their spiritual struggle. While eremitic monks did have an element of socializing, since they would meet once a week to pray together, cenobitic monks came together for common prayer on a more regular basis.[2] The cenobitic monks also practiced more socializing because the monasteries where they lived were often located in or near inhabited villages. For example, the Bohairic version of the Life of Pachomius states that the monks of the monastery of Tabenna built a church for the villagers of the nearby town of the same name even "before they constructed one for themselves."[2] This means that cenobitic monks did find themselves in contact with other people, including lay people, whereas the eremitic monks tried their best to keep to themselves, only meeting occasionally, for prayer.

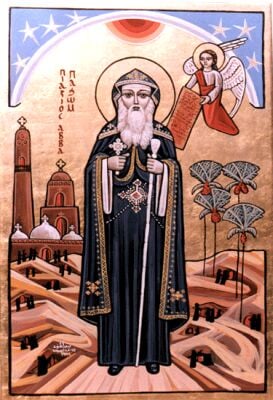

Cenobitic monks were also different from their eremitic predecessors and counterparts in their actual living arrangements. The eremitic monks lived alone, as they were hermits, whereas the cenobitic monks lived together in small houses or monasteries. Each dwelling would house about twenty monks and within the house there were separate rooms or "cells" that would be inhabited by two or three monks.[1] This structure of living for the cenobitic monks has been attributed to the same man that is usually hailed as the "father of cenobitic monasticism," Saint Pachomius. Pachomius is thought to have gotten the idea for living quarters like these from the time he spent in the Roman army, because the style is very "reminiscent of army barracks."[3]

Though Pachomius is often credited as the "father of cenobitic monasticism," in actuality it is better to think of him as the "father of organized cenobitic monasticism" as he was the first monk to take smaller communal groups that often already existed and bring them together into a larger federation of monasteries.[3]

The account of how Pachomius was given the idea to start a cenobitic monastery is found in Palladius' The Lausiac History, and says that an angel came to Pachomius to give him the idea.[4] Though this is an interesting explanation for why he decided to initiate the cenobitic tradition, there are sources that indicate there were actually other communal monastic communities around at the same time as Pachomius, and possibly even before him. In fact, three of the nine monasteries that joined Pachomius' cenobitic federation were not founded by him, meaning he actually was not the first to have such an idea, since these three clearly had an independent origin.[5]

Aside from the monasteries that joined Pachomius' federation of cenobitic monasteries, there were also other cenobitic Christian groups who decided not to join him. The Melitians and the Manichaeans are examples of these cenobitic groups. Even before Pachomius had started on his path toward monastic communities, the Melitians were a group already recruiting members. They actually had "heard of Pachomius' monastic aspirations and tried to recruit him" to join their community.[6]

As for Manichaeans, a group founded by a man named Mani, some scholars believe they were the "pioneers of communal asceticism in Egypt,"[3] and not Pachomius and the Pachomians as has become the common thought. Mani, himself, was actually influenced to begin cenobitic monasticism from other groups, including Buddhists and Jewish-Christian Elkasites who were practicing this tradition already.

Though he was not the first to implement communal monasticism, Pachomius is still an important part of cenobitic monastic history, since he was the first to bring differing separate monasteries together into a more organized structure. This is the reason why (as well as the fact that much hagiography and literature has been written about him) he has continued to be recognized as the father of the tradition.

The overall idea of cenobitic monasticism cannot be traced to any single source, however, as many have suggested in calling Pachomius the "founder" of the tradition,. It is more accurate to say that the ideas and practice of cenobitic monasticism derives from numerous groups, including the aforementioned Melitians, Manichaeans, Elkasites, Buddhists, and, of course, the Pachomians.

Cenobitic monasticism did not end with these groups, though, inspiring future groups and individuals:

- Mar Awgin founded a monastery on Mt. Izla above Nisibis in Mesopotamia (~350), and from this monastery the cenobitic tradition spread in Mesopotamia, Persia, Armenia, Georgia, and even India and China.

- Mar Saba organized the monks of the Judean Desert in a monastery close to Bethlehem (483), and this is considered the mother of all monasteries of the Eastern Orthodox churches.

- St. Benedict of Nursia founded the monastery of Monte Cassino in Italy (529), which was the seed of Roman Catholic monasticism in general, and of the order of Benedict in particular.

- St. Bruno of Carthusia, prompted by the specter of the damnation of the Good Doctor of Paris Cenodoxus, founded a monastery just outside of Paris in the eleventh century.

In both the East and the West, cenobiticism established itself as the primary form of monasticism, with many foundations being richly endowed by rulers and nobles. The excessive acquisition of wealth and property led to several attempts at reform, such as Bernard of Clairvaux in the West and Nilus of Sora in the East.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 C.H. Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, 3rd edition (Toronto: Pearson Education Limited, 2003, ISBN 978-0582404274).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 James E. Goehring, "Withdrawing from the Desert: Pachomius and the development of Village Monasticism in Upper Egypt," Harvard Theological Review 89(3) (1996), 267-285. Retrieved April 10, 2025.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Marilyn Dunn, The Emergence of Monasticism: From the Desert Fathers to the Early Middle Ages (Blackwell Publishers, 2000, ISBN 978-1405106412).

- ↑ Paul Halsall, Medieval Sourcebook: Palladius: The Lausiac History. Retrieved April 10, 2025.

- ↑ James E. Goehring, Ascetics, Society, and the Desert: Studies in Early Egyptian Monasticism (Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 1999, ISBN 978-1563382697).

- ↑ William Harmless, Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0195162233).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brooke, Christopher. The Age of the Cloister: The Story of Monastic Life in the Middle Ages. HiddenSpring, 2003. ISBN 978-1587680182

- Dunn, Marilyn. The Emergence of Monasticism: From the Desert Fathers to the Early Middle Ages. Blackwell Publishers, 2000. ISBN 978-1405106412

- Goehring, James E. Ascetics, Society, and the Desert: Studies in Early Egyptian Monasticism. Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 1999. ISBN 978-1563382697

- Harmless, William. Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0195162233

- Johnston, William M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Monasticism. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000. ISBN 978-1579580902

- Lawrence, C.H. Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages, 3rd Edition. Longman, 2003. ISBN 978-0582404274

- Plaiss, Mark. The Inner Room: A Journey into Lay Monasticism. Saint Anthony Messenger Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0867164817

- Sloan, Karen E. Flirting With Monasticism: Finding God on Ancient Paths. IVP Books, 2006. ISBN 0830836020

- Wijayaratna, Mohan. Buddhist Monastic Life: According to the Texts of the Theravada Tradition. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0521367080

External links

All links retrieved April 10, 2025.

- The Mystery of Cenobitic Monastic Life Monastic Congregation of St. Benedict

- What are the three types of monastic? Sewofworld Poland

- St. Pachomius and Cenobitic Monasticism Lessons from a Monastery

- Saint Pachomios the Great and Founder of Cenobitic Monasticism Orthodox Metropolitanate of Hong Kong and South East Asia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.