Nuclear physics

| Nuclear physics | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Radioactive decay Nuclear fission Nuclear fusion

| ||||||||||||||

Nuclear physics is a field of physics that involves investigation of the building blocks and interactions of atomic nuclei. It includes studies of nuclear components such as protons and neutrons, forces such as the strong force (or strong interaction), and phenomena such as radioactive decay, nuclear fission, and nuclear fusion.

Nuclear power and nuclear weapons are the most commonly known applications of nuclear physics, but the research field is also the basis for a far wider range of less common applications, such as in medicine (nuclear medicine, magnetic resonance imaging), materials engineering (ion implantation), and archaeology (radiocarbon dating).

Related fields

Nuclear physics is sometimes used synonymously with atomic physics, but physicists usually differentiate between the two. Atomic physics studies the combined system of the atomic nucleus and the arrangement of electrons around the nucleus.

Particle physics involves study of the elementary constituents of matter and radiation, and the interactions between them. Particle physics evolved out of nuclear physics and, for this reason, has been included under the same term in earlier times.

History

The discovery of the electron by J. J. Thomson was the first indication that the atom had internal structure. At the turn of the twentieth century, the accepted model of the atom was J. J. Thomson's "plum pudding" model, in which the atom was a large positively charged ball with small negatively charged electrons embedded inside it. By then, physicists had also discovered three types of radiation coming from atoms, which they named alpha, beta, and gamma radiation.

Experiments by Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn in 1911 and James Chadwick in 1914 showed that the beta decay spectrum was continuous rather than discrete. That is, electrons were ejected from the atom with a range of energies, rather than the discrete amounts of energies that were observed in gamma and alpha decays. This was a problem for nuclear physics at the time, because it indicated that energy was not conserved in these decays.

In 1905, Albert Einstein formulated the idea of mass–energy equivalence. While the work on radioactivity by Becquerel, Pierre and Marie Curie predated this, an explanation of the source of the energy of radioactivity had to await the discovery that the nucleus itself was composed of smaller constituents, the nucleons.

Rutherford's team discovers the nucleus

In 1906, Ernest Rutherford published "Radiation of the α Particle from Radium in passing through Matter."[1] Hans Geiger expanded on this work in a communication to the Royal Society[2] with experiments he and Rutherford had done passing α particles through air, aluminum foil and gold leaf. More work was published in 1909, by Geiger and Ernest Marsden,[3] and was greatly expanded in 1910 by Geiger.[4] In 1911-12, Rutherford went before the Royal Society to explain the experiments and propound the new theory of the atomic nucleus as we now understand it.

The key experiment behind this announcement was performed in 1909, when Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, under Rutherford's supervision, fired alpha particles (helium nuclei) at a thin film of gold foil. The plum pudding model predicted that the alpha particles should come out of the foil with their trajectories being at most slightly bent. Their actual observations, however, were shocking: A few particles were scattered through large angles, with some bouncing completely backwards.

Those observations, upon analysis, led to the Rutherford model of the atom, in which the atom has a very small, dense nucleus containing most of its mass, and consisting of heavy positively charged particles with several embedded electrons that would (at least partially) balance out the charge (since the neutron was unknown). As an example of this model (which is not the modern one), nitrogen-14 was thought to consist of a nucleus with 14 protons and 7 electrons (21 total particles), and the nucleus was surrounded by 7 more orbiting electrons.

The Rutherford model worked quite well until studies of nuclear spin were carried out by Franco Rasetti at the California Institute of Technology in 1929. By 1925, it was known that protons and electrons had a spin of 1/2, and in the Rutherford model of nitrogen-14, 20 of the 21 particles should have paired up to cancel each other's spin, and the final odd particle should have left the nucleus with a spin of 1/2. Rasetti discovered, however, that nitrogen-14 has a spin of 1.

Chadwick discovers the final necessary particle

In 1932, Chadwick realized that radiation that had been observed by Walther Bothe, Herbert L. Becker, and Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie was actually due to a neutral particle of about the same mass as the proton, that he called the neutron (following a suggestion about the need for such a particle, by Rutherford). That same year, Dmitri Ivanenko suggested that neutrons were in fact spin 1/2 particles and that the nucleus contained neutrons to explain the mass not due to protons, and that there were no electrons in the nucleus—only protons and neutrons. The neutron spin immediately solved the problem of the spin of nitrogen-14, as the one unpaired proton and one unpaired neutron in this model, each contribute a spin of 1/2 in the same direction, for a final total spin of 1.

With the discovery of the neutron, scientists could at last calculate what fraction of binding energy each nucleus had, from comparing the nuclear mass with that of the protons and neutrons that composed it. Differences between nuclear masses calculated in this way, and when nuclear reactions were measured, where found to agree with Einstein's calculation of the equivalence of mass and energy to high accuracy (within 1 percent, when calculated in 1934).

Yukawa's meson postulated to bind nuclei

In 1935, Hideki Yukawa proposed the first significant theory of the strong force to explain how neutrons and protons are held together in the nucleus. In the Yukawa interaction, a virtual particle, later called a meson, mediated a force between all nucleons, including protons and neutrons. This force explained why nuclei did not disintegrate under the influence of proton repulsion, and it also gave an explanation of why the attractive strong force had a more limited range than the electromagnetic repulsion between protons. Later, the discovery of the pi meson showed it to have the properties of Yukawa's particle.

With Yukawa's papers, the modern model of the atom was nearing completion. The center of the atom contains a tight ball of neutrons and protons, which is held together by the strong nuclear force, unless the nucleus is too large. Unstable nuclei may undergo alpha decay, when they emit an energetic helium nucleus, or beta decay, when they eject an electron (or positron). After one of these decays, the resultant nucleus may be left in an excited state, and in this case it decays to its ground state by emitting high energy photons (gamma decay).

The study of the strong and weak nuclear forces (the latter explained by Enrico Fermi via Fermi's interaction in 1934) led physicists to collide nuclei and electrons at ever higher energies. This research became the science of particle physics, the crown jewel of which is the standard model of particle physics, which unifies the strong, weak, and electromagnetic forces.

Modern nuclear physics

A heavy nucleus can contain hundreds of nucleons, which means that with some approximation it can be treated as a classical system, rather than a quantum-mechanical one. In the resulting liquid-drop model, the nucleus has an energy that arises partly from surface tension and partly from electrical repulsion of the protons. The liquid-drop model is able to reproduce many features of nuclei, including the general trend of binding energy with respect to mass number, as well as the phenomenon of nuclear fission.

Superimposed on this classical picture, however, are quantum mechanical effects, which can be described using the nuclear shell model, developed in large part by Maria Goeppert-Mayer. Nuclei with certain numbers of neutrons and protons (the magic numbers 2, 8, 20, 50, 82, 126, …) are particularly stable, because their shells are filled.

Other, more complicated models for the nucleus have also been proposed, such as the interacting boson model, in which pairs of neutrons and protons interact as bosons, analogously to Cooper pairs of electrons.

Much of current research in nuclear physics relates to the study of nuclei under extreme conditions, such as high spin and excitation energy. Nuclei may also have extreme shapes (similar to that of American footballs) or extreme neutron-to-proton ratios. Experimenters can create such nuclei using artificially induced fusion or nucleon transfer reactions, employing ion beams from a particle accelerator. Beams with even higher energies can be used to create nuclei at very high temperatures, and there are signs that these experiments have produced a phase transition from normal nuclear matter to a new state, the quark-gluon plasma, in which quarks mingle with one another, rather than being segregated in triplets as they are in neutrons and protons.

Modern topics in nuclear physics

Nuclear decay: Spontaneous changes from one nuclide to another

There are 80 elements that have at least one stable isotope, and 250 such stable isotopes. However, there are thousands more well-characterized isotopes that are unstable. These radioisotopes may be unstable and decay along timescales ranging from fractions of a second to weeks, years, or even many millions of years.

If a nucleus has too few or too many neutrons it may be unstable, and will decay after some period of time. For example, in a process called beta decay, a nitrogen-16 atom (7 protons, 9 neutrons) is converted to an oxygen-16 atom (8 protons, 8 neutrons) within a few seconds of being created. In this decay, a neutron in the nitrogen nucleus is turned into a proton and an electron and antineutrino, by the weak nuclear force. The element is transmuted to another element in the process because, while it previously had seven protons (which makes it nitrogen), it now has eight (which makes it oxygen).

In alpha decay, the radioactive element decays by emitting a helium nucleus (2 protons and 2 neutrons), giving another element, plus helium-4. In many cases this process continues through several steps of this kind, including other types of decays, until a stable element is formed.

In gamma decay, a nucleus decays from an excited state into a lower energy state by emitting a gamma ray. The element is not changed in the process.

Other, more exotic decays, are also possible. For example, in internal conversion decay, the energy from an excited nucleus may be used to eject one of the inner orbital electrons from the atom. This process produces high speed electrons, but it is not beta decay, and (unlike beta decay) does not transmute one element to another.

Nuclear fusion

When two light nuclei come into very close contact with each other, it is possible for the strong force to fuse the two together. It takes a great deal of energy to push the nuclei close enough together for the strong or nuclear forces to have an effect, so the process of nuclear fusion can take place only at very high temperatures or high densities. Once the nuclei are close enough together, the strong force overcomes their electromagnetic repulsion and squishes them into a new nucleus. A very large amount of energy is released when light nuclei fuse together because the binding energy per nucleon increases with mass number up until nickel-62.

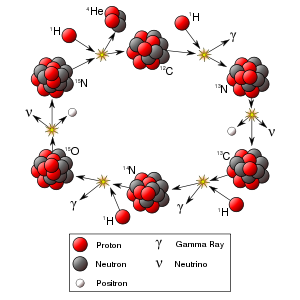

Stars like the Sun are powered by the fusion of four protons into a helium nucleus, two positrons, and two neutrinos. The uncontrolled fusion of hydrogen into helium is known as thermonuclear runaway. Research to find an economically viable method of using energy from a controlled fusion reaction is currently being undertaken by various research establishments.

Nuclear fission

For nuclei heavier than nickel-62, the binding energy per nucleon decreases with mass number. It is therefore possible for energy to be released if a heavy nucleus breaks apart into two lighter ones. This splitting of atomic nuclei is known as nuclear fission.

The process of alpha decay may be thought of as a special type of spontaneous nuclear fission. This process produces a highly asymmetrical fission because the four particles that make up the alpha particle are especially tightly bound to each other, making production of this nucleus in fission particularly likely.

For some of the heaviest nuclei that produce neutrons on fission, and which also easily absorb neutrons to initiate fission, a self-igniting type of neutron-initiated fission can be obtained, in a so-called chain reaction. [Chain reactions were known in chemistry before physics, and in fact many familiar processes like fires and chemical explosions are chemical chain reactions].

The fission or "nuclear" chain-reaction, using fission-produced neutrons, is the source of energy for nuclear power plants and fission type nuclear bombs such as the two that the United States used against Hiroshima and Nagasaki to bring an end to World War II in the Pacific theater. Heavy nuclei such as uranium and thorium may undergo spontaneous fission, but they are much more likely to undergo alpha decay.

For a neutron-initiated chain-reaction to occur, there must be a critical mass of the element present in a certain space under certain conditions (these conditions slow and conserve neutrons for the reactions). There is one known example of a natural nuclear fission reactor, which was active in two regions of Oklo, Gabon, Africa, over 1.5 billion years ago. Measurements of natural neutrino emission have demonstrated that around half of the heat emanating from the Earth's core results from radioactive decay. However, it is not known if any of this results from fission chain-reactions.

Production of heavy elements

As the Universe cooled after the Big Bang, it eventually became possible for particles as we know them to exist. The most common particles created in the Big Bang that are still easily observable to us were protons (hydrogen) and electrons (in equal numbers). Some heavier elements were created as the protons collided with each other, but most of the heavy elements we see today were created inside of stars during a series of fusion stages, such as the proton-proton chain, the CNO cycle, and the triple-alpha process.

Progressively heavier elements are created during the evolution of a star. Since the binding energy per nucleon peaks around iron, energy is released only through fusion processes occurring below this point. Since the creation of heavier nuclei by fusion costs energy, nature resorts to the process of neutron capture. Neutrons (due to their lack of charge) are readily absorbed by a nucleus. The heavy elements are created by either a slow neutron capture process (the so-called s process) or by the rapid (or r) process. The s process occurs in thermally pulsing stars (called AGB, or asymptotic giant branch stars) and takes hundreds to thousands of years to reach the heaviest elements of lead and bismuth. The r process is thought to occur in supernova explosions because the conditions of high temperature, high neutron flux and ejected matter are present. These stellar conditions make the successive neutron captures very fast, involving very neutron-rich species, which then undergo beta decay to heavier elements, especially at the so-called waiting points that correspond to more stable nuclides with closed neutron shells (magic numbers). The r process duration is typically in the range of a few seconds.

See also

- Atom

- Atomic physics

- CNO cycle

- Electron

- Elementary particle

- Neutron

- Nuclear fission

- Nuclear fusion

- Nuclear power

- Nuclear weapon

- Particle physics

- Proton

- Quark

- Radioactive decay

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bertulani, Carlos A. 2007. Nuclear Physics in a Nutshell. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691125053.

- Kaplan, Irving. 1964. Nuclear Physics, 2nd ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. OCLC 174670641.

- Lilley, J. S. 2001. Nuclear Physics: Principles and Applications. The Manchester Physics Series. Chichester, UK: Wiley. ISBN 0471979368.

- Martin, Brian R. 2006. Nuclear and Particle Physics: An Introduction. Chichester, UK: Wiley. ISBN 978-0470019993.

- Pauling, Linus. 1988. General Chemistry. New York: Dover Pub. ISBN 0486656225.

External links

All links retrieved November 16, 2022.

- American Nuclear Society.

- Nucleonica: web driven nuclear science. European Commission.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.