| Saint Bonaventura | |

|---|---|

| the Devout Doctor | |

| Born | 1221, Bagnoregio, Italy |

| Died | July 15,1274 Lyon, France |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Canonized | April 14, 1482 |

| Feast | July 15 |

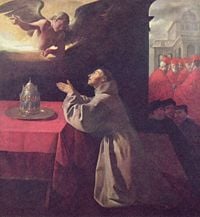

| Attributes | Cardinal's hat; ciborium; Holy Communion; Cardinal in Franciscan robes, usually reading or writing |

Saint Bonaventura also Bonaventure (born Giovanni di Fidanza) (1221 - July 15, 1274), was a Franciscan theologian, philospher, general of the Franciscan Friars Minor, and cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He set forth a mystical and Platonic view of God and the universe, with a primary focus on attaining oneness with God in the afterlife. His book “Journey to the Mind of God” and several smaller works outlined a detailed process by which man could come to know God. Appointing God the “Father of Light” and teaching that the principle of truth is a divine light within us, he wrote that the mind contemplating God had three phases; the senses, reason and pure intellect, each of which could lead to an understanding of a different aspect of God. Through the senses and reason, man could appreciate the greatness of God; through the practice of Christian virtues such as faith, hope and charity, man could come to understand God’s love. The final stage, pure intellect, required a spark of divine illumination and resulted in a state where the mind rests in the contemplation of the infinite goodness of God. The monastic life of asceticism was the best means to achieve this state.

Bonaventura was a moderate scholastic theologian. He rejected Aristotle’s concept of the eternity of the world, but incorporated some Aristotelian elements in his theology. He considered universals to be ideal forms pre-existing in the divine mind, according to which all things were shaped.

Early Life

Bonaventure was born Giovanni di Fidanza, in either 1217 or 1221, at Bagnoregio in Latium, not far from Viterbo Province. His father was a physician, Giovanni di Fidanza. His mother was Maria di Ritello, or simply Ritella, and his grandfather was Fidanza. He is said to have received the cognomen of Bonaventura when he was cured from a serious childhood illness through the intercession of Saint Francis of Assisi. He received his early schooling at the Franciscan friary in Bagnoregio. He demonstrated substantial academic ability and began his studies at the University of Paris in 1235 or 1236. There Bonaventure met many members of the Franciscan order, and after gaining a Master of Arts degree he entered the order (Friars Minor) in either 1238 or 1243. Soon after entering the order he received the name Bonaventure.

He studied theology at the Franciscan school in Paris for five years, possibly under Alexander of Hales, and certainly under Alexander's successor, John of Rochelle (to whose chair he succeeded in 1253). During those years Bonaventure was a teacher to the Franciscan brothers. In 1248, he became a lecturer on the Bible. From 1250 to 1253, he gave lectures on “The Books of Opinions of Peter Lombard” and prepared to receive a licentiate and doctorate in theology from the University of Paris. He was elected the minister general of the Friars Minor, resigned his responsibilities at the university, made Paris his headquarters and began to preach. At that period, Paris was a center for theological studies. When Thomas Aquinas began his studies in Paris in 1252, he formed a friendship with Bonaventura.

In 1255 he received the degree of master, the medieval equivalent of doctor. In the year after having successfully defended his order against the reproaches of the anti-mendicant party, he was elected general of his order. It was by his order that Roger Bacon, a Franciscan Friar himself, was interdicted from lecturing at Oxford, and compelled to put himself under the surveillance of the order at Paris.

Works

Bonaventura produced several important works during the years between 1248 and 1257. In 1257 he wrote a concise handbook of theology named “the Breviloquium,” “Retracing the Arts to Theology” (date unknown), and in 1259, “The Journey of the Mind to God,” an integration of meditative and mystical theology written at La Verna. In 1260 Bonaventura was charged with writing a new biography of Saint Francis. While gathering materials to write it, he visited many places and interviewed the early friars. In 1263 he presented each of the 34 provincials with a copy of “The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi.” In 1265, he presented himself to Pope Clement IV who offered Bonaventura the post of Archbishop of York, but he declined. In 1273, in Paris, he started work on “Collations on the Six Days” which was theological evidence to confute those who insisted on following Aristotelian rationalism.

Bonaventura was instrumental in procuring the election of Gregory X, who rewarded him with the titles of Cardinal and Bishop of Albano in Italy in 1273, and insisted on his presence at the great Council of Lyon in the year 1274. There, after making significant efforts to bring about a union of the Greek and Latin Churches, he died. The only extant relic of Saint Bonaventura is the arm and hand with which he wrote his great Commentary on the Four Books of Peter Lombard, which is now conserved at Bagnoregio, in the parish Church of Saint Nicholas.

The eulogistic title, "Doctor Seraphicus," was bestowed on Bonaventure by his contemporaries. He was formally canonized in 1482 by the Conventual Franciscan Sixtus IV, and ranked along with Saint Thomas Aquinas as the greatest doctors of the church by the Conventual Franciscan, Sixtus V, in 1587. The works of Bonaventura, as arranged in the most recent Critical Edition of his works, by the Quaracchi Fathers (Collegio S. Bonaventura), consist of a Commentary on the Sentences of Lombard in four volumes; and eight other volumes, including a Commentary on the Gospel of St. Luke and a number of smaller works; the most famous of which are Itinerarium Mentis ad Deum, Breviloquium, De Reductione Artium ad Theologiam, Soliloquium, and De septem itineribus aeternitatis. These smaller works contain the portions of his teachings which were original.

The Journey of the Mind to God

An anecdote about Bonaventura and Thomas Aquinas relates that when Thomas visited Bonaventura’s office and asked to peruse his collection of books, Bonaventura immediately stood up and pointed at the Christ on the cross.

The Journey of the Mind to God (Itinerarium Mentis ad Deum), Bonaventura’s masterpiece, was published in 1259. Through this small text, Bonaventura portrayed the ultimate goal of life as the “Love of God,” which could be reached through Christ, and depicted human life as the process of reaching God. Six stages of the powers of the soul correspond to the six stages of ascension to God. Knowledge of God is not an affair of the intellect; love goes far beyond reason. The ultimate stage is the abandonment of the intellectual powers of the mind in the mystical knowledge of God.

Philosophy

Background

The conflict between Augustine and Aristotle

During the Middle Ages, from the 1220s until the sixteenth century, scholars used The Four Books of Sentences as a standard text by Peter Lombard. Most famous medieval scholars, including Bonaventura, Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham and even Martin Luther wrote commentaries on “Sentences.” The thirteenth century can be divided three periods of theological development, with the first period represented by Bonaventura, the second by Thomas Aquinas and the third by Duns Scotus. Bonaventura inherited the theology and faith of St. Augustine and Saint Francis. Several significant cultural events shaped the character of the thirteenth century. The Crusades brought highly developed Jewish and Islamic culture to the West. The next important influence was the rediscovery of Aristotle’s scientific and systematic philosophy, which was so methodologically superior to Saint Augustine’s theology that the Church took special precautions against it. Another influence was the emergence of new types of monastic mendicant orders such as the Franciscans and the Dominicans. Francis of Assisi observed the monasticism of Saint Augustine and Bernard and, in the tradition of Anselm, Saint Augustine and Bernard, emphasized personal experience and a deep relationship with nature, which belongs to the Divine. The legend of Francis is depicted in the paintings of Giotto.

Dominic bore the responsibility of preaching and defending the faith. The Dominicans later became the leading instrument of the Inquisition. The Dominican order produced eminent theological scholars, among them, Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. The Franciscan –Augustinian tradition emphasized the will more than the intellect, whereas Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas brought Aristotle to the West. The theological world of the Middle Ages was characterized by disputes between the Franciscans, who were influenced by St. Augustine and the Dominicans, who were influenced by Aristotle.

Bonaventure’s theory followed the current of the Augustinians, who, in contrast to Aristotelians, put God first. The concept of “God the first” is difficult for the modern mind to grasp. In the Augustinian tradition, Bonaventure appointed God the first principle and center, the “Father of Light,” saying, “He is most truly present to the soul and immediately knowable.” The principle of truth was the divine light within us. (This doctrine of inner light was used by mystical movements throughout the Middle Ages and during the time of the Reformation. Even in the seventeenth century, George Fox claimed that Christ is the inner light.) We start with our knowledge of God and go out to the world. Bonaventure said that, “Being itself is what first appears in the intellect.” This divine light and the principles within us are uncreated. The tradition of Augustine and Bonaventure is termed “theonomous,” meaning that God is prior to all conclusions. Thomas Aquinas held the opposite view, that these principles are created light, and not uncreated light. They are not the divine presence within us, but works of God within us. We do not carry the infinite within us, but we begin with the finite and discover God in our act of cognition. The thought of Thomas Aquinas, which incorporated Aristotelian logic, was a sign that a secular system of ideas was emerging. The scholars of the Middle Ages could not incorporate the secular world into Augustinian ecclesiastical tradition. Aristotelianism provided a new approach to knowledge and metaphysics, and emphasized the importance of experience. For the Augustinians, however, it posed a serious threat. One of Bonaventure’s disciples warned that the moment a man began to follow pursue the Aristotelian thinking of Thomas Aquinas, he would mislay the principles.

In philosophy Bonaventure presents a marked contrast to his contemporaries, Roger Bacon and Thomas Aquinas. While Roger Bacon represents physical science in its infancy, and Thomas Aquinas, Aristotelian scholasticism in its most perfect form, Bonaventure exhibits a mystical and Platonizing mode of speculation which had already to some extent found expression in Hugo and Richard of St. Victor, and in Bernard of Clairvaux. For him, the purely intellectual element is less important than the power of the affections or the heart. He uses the authority of Aristotle in harmony with Scriptural and Patristic texts, and attributes the heretical tendency of the age to an attempt at divorcing Aristotelian philosophy from Catholic theology. Like St. Thomas Aquinas, with whom he agreed in numerous theological and philosophical matters, he vigorously refuted the Aristotelian notion of the eternity of the world. His Platonism was Plato as understood by St Augustine, which had been handed down by the Alexandrian school and the author of the mystical works passing under the name of Dionysius the Areopagite.

Knowledge of God

Bonaventura accepts as Platonic the theory that ideas do not exist in rerum natura, but as ideals exemplified by the Divine Being, according to which actual things are formed; and this concept permeates his philosophy. Like all the great scholastic doctors, he starts with a discussion of the relationship between reason and faith. All the sciences are in the service of theology; the mind can use reason to discover some of the moral truths which form the groundwork of the Christian system, but others can only be received and apprehended through divine illumination. In order to obtain this illumination, the soul must employ the proper means, which are prayer; the exercise of the virtues, whereby it is rendered fit to accept the divine light; and meditation in which it may even rise to ecstatic union with God. The supreme end of life is such a union, in contemplation or intellect and in intense absorbing love; but this cannot be entirely reached during this life, and remains as a hope for the future.

The mind contemplating God has three distinct aspects or stages: the senses, which give empirical knowledge of what is without and discern the traces (vestigia) of the divine in the world; the reason, which examines the soul, itself the image of the divine Being; and lastly, pure intellect (intelligentia), which, in a transcendent act, grasps the Being of the divine cause. To these three correspond three kinds of theology-theologia symbolica, theologia propria and theologia mystica. Each stage of contemplation is subdivided; in contemplating the outer world, we may use the senses or the imagination, and we may rise to a knowledge of God per vestigia or in vestigiis. In the former case we are irresistibly led to acknowledge the power, wisdom and goodness of the Triune God by the three great properties of physical bodies, weight, number, and measure; in the latter, by the division of created things into the classes of those that have merely physical existence, those that have life, and those that have thought. In the second stage we may ascend to the knowledge of God by reason (per imaginem), or by pure understanding (intellectus) Reason encompasses the triple faculties of memory, understanding and will; understanding encompasses the three Christian virtues of faith, hope and charity; leading to the concept of a Trinity with the three divine qualities of eternity, truth and goodness.

The last stage, pure intellect, has first intelligentia, (pure intellect), contemplating the essential being of God, and finding itself compelled by necessity to hold absolute being as the first notion, for non-being cannot be conceived apart from being. To this notion of absolute being, which is perfect and the greatest of all, objective existence must be ascribed. In its final and highest form of activity, the mind rests in the contemplation of the infinite goodness of God, apprehended by means of the highest faculty, the apex mentis or synderesis. This spark of the divine illumination is common to all forms of mysticism, but Bonaventura adds to it peculiarly Christian elements. The complete yielding up of mind and heart to God is unattainable without divine grace, and nothing renders us so fit to receive this gift as the meditative and ascetic life of the cloister. The monastic life is the best means of grace.

Scholastic philosophy

Bonaventura was not merely a meditative thinker, whose works could be used as manuals of devotion; he was a dogmatic theologian of high rank, and on all the disputed questions of scholastic thought, such as universals, matter, the principle of individualism, or the intellectus agens, he gave weighty and well-reasoned decisions. He agreed with Albertus Magnus that theology should be regarded as a practical science; its truths, according to his view, were peculiarly adapted to influence the affections. He discussed very carefully the nature and meaning of the divine attributes; considered universals to be the ideal forms pre-existing in the divine mind, according to which things were shaped; held matter to be pure potentiality which receives individual being and determinateness from the formative power of God, acting according to the ideas; and finally maintained that the intellectus agens has no separate existence. On these and on many other points of scholastic philosophy Bonaventure exhibited a combination of subtlety and moderation, which made his works particularly valuable.

Namesakes

Ventura, California and Ventura County, California are named for Saint Bonaventure, as is Bonaventure, Quebec.

St. Bonaventure University, the largest Franciscan university in the English-speaking world, is located in Western New York. St. Bonaventure's College is a private Roman Catholic school located in Newfoundland, Canada. And St. Bonaventure College and High School is located in Hong Kong. St. Bonaventure's Catholic Comprehensive School is located in Forest Gate, London.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bettoni, Efrem; Angelus Gambatese, (trans.). Saint Bonaventure. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre dame Press, 1964. ASIN B00BDEIIC4

- Copleston, Frederick. A History of Philosophy: Medieval Philosophy. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0268010911

- Cousins, Ewert. Bonaventure and the Coincidence of Opposites: The Theology of Bonaventure. Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0819905802

- Prentice, Robert P. The Psychology of Love According to St. Bonaventure, 3rd ed. The Franciscan Institute, 1992. ASIN B0006P75RK

- Shahan, Robert W. and Francis J. Kovach, (eds.) Bonaventure and Aquinas: Enduring Philosophers. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976. ASIN B00129K1UW

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2023.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Links to Bonaventura

- Patron Saint Saint Bonaventure Catholic Community

- General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.