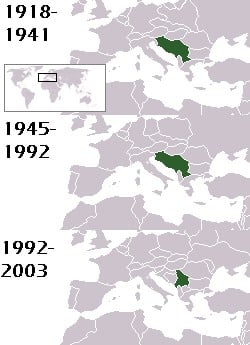

Yugoslavia describes three political entities that existed one at a time on the Balkan Peninsula in Europe, during most of the twentieth century.

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( December 1, 1918,‚ÄďApril 17, 1941), also known as the First Yugoslavia, was a monarchy formed as the "Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes" after World War I and re-named on January 6, 1929, by Alexander I of Yugoslavia. It was invaded on April 6, 1941, by the Axis powers and capitulated 11 days later.

The Second Yugoslavia (November 29, 1943,‚ÄďJune 25, 1991), a socialist successor state to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, existed under various names, including the "Democratic Federation of Yugoslavia (DFY)" (1943), the "Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY)" (1946), and the "Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY)" (1963). It disintegrated in the Yugoslav Wars, which followed the secession of most of the constituent elements of SFRY.

The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) (April 27, 1992,‚ÄďFebruary 4, 2003), was a federation on the territory of the two remaining republics of Serbia (including the autonomous provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo and Metohija) and Montenegro.

The Union of Serbia and Montenegro was formed on February 4, 2003, and officially abolished the name "Yugoslavia." On June 3 and June 5, 2006, Montenegro and Serbia respectively declared their independence, thereby ending the last remnants of the former Yugoslav federation.

The region once occupied by Yugoslavia is often described as "the crossroads between East and West." This position is considered one of the reasons for its turbulent history.

Geography

Yugoslavia, with a land area of 98,610 square miles (255,400 square kilometers), in 1990 was slightly larger than Wyoming in the United States. The area controlled the most important land routes from central and western Europe to Aegean Sea and Turkish straits. The nation shared borders with Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, Italy, and Romania.

The territory’s terrain is extremely varied, with rich fertile plains to the north, limestone ranges and basins to the east, ancient mountains and hills to the southeast, and extremely high shoreline with no islands off the coast to the southwest. The highest point is Daravica at 8713 feet (2656 meters).

Natural resources include coal, copper, bauxite, timber, iron ore, antimony, chromium, lead, zinc, asbestos, mercury, crude oil, natural gas, nickel, and uranium. Twenty eight percent of the land is considered arable.

Background

The area that became Yugoslavia has been the location of pre-human and human habitation for 100,000 years. The remnants of a Neanderthal, subsequently named Homo krapiniensis, were discovered on a hill near the town of Krapina, in Croatia. The Balkans were home to the iron-working Illyrians, who settled through the western Balkans by the seventh century B.C.E., and iron-skilled Celts began to settle the area from 300 B.C.E. Romans began to move into the Balkan Peninsula in the late third century B.C.E., conquered Illyria in 168 B.C.E., and organized the land into the Roman province of Illyricum.

The first idea of a state for all South Slavs emerged in the late seventeenth century, a product of visionary thinking of Croat writers and philosophers who believed that the only way for southern Slavs to regain lost freedom after centuries of occupation under the various empires would be to unite and free themselves of tyrannies and dictatorships. They named it the Illyrian Movement and gathered many prominent Croatian intellectuals and politicians around the new idea, but the movement started gaining large momentum only at the end of the nineteenth century, mainly because of the policies against freedom movements of southern Slavs. However, ideas for a unified state did not mature from the conceptual to practical state of planning and few of those promoting such an entity had given any serious consideration to what form the new state should take.

During the early period of World War I, a number of prominent political figures from South Slavic lands under the Habsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire fled to London, where they began work on forming the Yugoslav Committee to represent the Southern Slavs of Austria-Hungary. These "Yugoslavs" were Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes who identified themselves with the movement toward a single Yugoslav or South Slavic state and the committee's basic aim was the unification of the South Slav lands with the Kingdom of Serbia (which was independent although occupied at the time).

With the defeat of the Central Powers in World War I and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, various South Slavic territories were quickly patched together to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes which was proclaimed on December 1, 1918 in Belgrade.

The new kingdom was made up of the formerly independent kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro (which had unified in the previous month), as well as a substantial amount of territory that was formerly part of Austria-Hungary, the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. The lands previously in Austria-Hungary that formed the new state included Croatia, Slavonia and Vojvodina from the Hungarian part of the Empire, Carniola, part of Styria and most of Dalmatia from the Austrian part, and the crown province of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

First Yugoslavia

The idea of a South Slav state emerged in the late seventeenth century among Croat writers and philosophers, in reaction to centuries of occupation. The so-named Illyric Movement started gaining large momentum only at the end of the nineteenth century, a result of oppression by Austrian and Hungarian dictators.

World War I

During the early period of World War I, a number of South Slavic prominent political figures, including Ante Trumbińá, Ivan MeŇ°trovińá, Nikola Stojadinovińá fled to London, where they formed the Yugoslav Committee on April 30, 1915, and began to raise funds, especially among South Slavs living in the Americas. While the committee's basic aim was the unification of the Habsburg south Slav lands with Serbia (which was independent at the time), its more immediate concern was to head off Italian claims in Istria and Dalmatia. In 1915, the Allies had lured Italy into the war with a promise of substantial territorial gains in exchange, and offered independent Serbia Bosnia, Herzegovina, Slavonia, Bańćka and parts of Dalmatia.

Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

During June and July of 1917, the Yugoslav Committee met the Serbian Government in Corfu, and on July 20 issued a declaration that laid the foundation for a post-war Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. As the Austrian Habsburg Empire dissolved, a National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs took power in Zagreb on October 5,1918. On October 29, the Croatian Sabor (parliament) declared independence and vested its sovereignty in the new State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, comprising the former kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro (including Serbian Macedonia), Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austrian land in Dalmatia and Slovenia, and Hungarian territory north of the Danube.

Quarrels broke out immediately about the terms of the proposed union. Croats wanted a federal structure respecting the diversity of traditions, while Serbs sought a unitary state to unite their scattered population. The 1921 constitution established a centralized state, under the Karadjordjevic dynasty of Serbia. The monarchy and the SkupŇ°tina (assembly) shared legislative power. The king appointed a council of ministers and retained control over foreign policy. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was declared on December 1, 1918, in Belgrade. The most prominent opponent of this decision was Stjepan Radińá, the leader of the Croatian Peasant Party. In 1921, on the death of his father, Alexander I inherited the throne of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

The assembly only considered legislation that had already been drafted, and local government only transmitted decisions made in Belgrade. The Croats soon came to resent the Serbian monarch and being governed from Belgrade, the Serbian capital. The Croatian Peasant Party under Stjepan Radińá boycotted the government of the Serbian Radical People's Party. In 1928, the UstaŇ°e (Ustashe) Party was formed to fight for independence, supported by Italy and Germany. In 1928, Radińá was mortally wounded during a Parliament session by PuniŇ°a Rańćińá, a deputy of the Serbian Radical People's Party.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

After ten years of acrimonious party struggle, in 1929 King Alexander I proclaimed a dictatorship, imposed a new constitution, and changed the name of the state to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He hoped to curb separatist tendencies and mitigate nationalist passions. He replaced the historical regions with nine prefectures (banovine), deliberately cutting across traditional ethnic boundaries and named after rivers. Many politicians were jailed or kept under tight police surveillance. The effect of Alexander's dictatorship was to further alienate the non-Serbs of the idea of unity. His policies soon ran into the obstacle of opposition from other European powers due to developments in Italy and Germany, where Fascists and Nazis rose to power, and the Soviet Union, where Joseph Stalin became absolute ruler. None of these three regimes favored the policy pursued by Alexander I.

Alexander was assassinated in Marseilles during an official visit to France in 1934 by a marksman from Ivan Mihailov‚Äôs IMRO in the cooperation of the UstaŇ°e, a Croatian separatist organization that pursued Nazi policies. Alexander I was succeeded by his 11-year-old son Peter II and a regency council headed by his cousin Prince Paul.

Supported and pressured by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, Croatian leader Vlatko Mańćek and his party managed the creation of the Croatian banovina (administrative province) in 1939. The agreement specified that Croatia was to remain part of Yugoslavia, but it was hurriedly building an independent political identity in international relations.

Under the monarchy, some industrial development took place, financed by foreign capital. The centralized government spent heavily on the military, created a bloated civil service, and intervened in industries and in marketing agricultural produce. By 1941, Yugoslavia was a poor rural state. More than 75 percent of the workforce was engaged in agriculture, birth rates were among the highest in Europe, and illiteracy rates were 60 percent in rural areas.

World War II

Prince Paul submitted to fascist pressure and signed the Tripartite Treaty in Vienna on March 25, 1941, hoping to keep Yugoslavia out of the war. But senior military officers opposed to the treaty launched a coup d'√©tat when the king returned on March 27. Army General DuŇ°an Simovińá seized power, arrested the Vienna delegation, exiled Paul to South Africa where he was kept under house arrest, and ended the regency, giving 17-year-old Peter II of Yugoslavia (September 6, 1923 ‚Äď November 3, 1970) full powers.

Adolf Hitler attack Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941. On April 17, representatives of Yugoslavia's various regions signed an armistice with Germany at Belgrade, ending 11 days of resistance against the invading German Wehrmacht. More than 300,000 Yugoslav officers and soldiers were taken prisoner. The Axis Powers occupied Yugoslavia and split it up. The Independent State of Croatia was established as a Nazi puppet-state, ruled by the Fascist UstaŇ°e militia. German troops occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as part of Serbia and Slovenia, while other parts of the country were occupied by Bulgaria, Hungary and Italy. During this time, the Independent State of Croatia created concentration camps for anti-fascists, communists, Serbs, Gypsies and Jews, one of the most famous being Jasenovac. A large number of men, women and children, mostly Serbs, were executed in these camps.

Following the pattern of other fascist puppet regimes in Europe, the Ustashi enacted racial laws, and formed eight concentration camps targeting minority Roma and Jewish populations. The main targets for persecution, however, where the minority Serbs, who were seen as a trojan horse of Serbian expansionism, and bore the brunt of retribution for the excesses of the Serb royal dictatorship of the First Yugoslavia.

In Serbia, the German authorities organized several concentration camps for Jews and members of the Partisan resistance movement. The biggest camps were Banjica and SajmiŇ°te near Belgrade, where approximately 40,000 Jews were killed. In all camps, some 90 percent of the Serbian Jewish population perished. In the Bańćka region annexed by Hungary, numerous Serbs and Jews were killed in 1942 raid by Hungarian authorities. The persecutions against ethnic Serb population occurred in the region of Syrmia, which was controlled by the Independent State of Croatia, and in the region of Banat, which was under direct German control.

Yugoslavs opposing the Nazis organized resistance movements. Those inclined towards supporting the old Kingdom of Yugoslavia joined the "Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland," also known as the Chetniks, a multi-ethnic, though largely Serb, royalist guerrilla army led by DraŇĺa Mihajlovińá. Those inclined towards supporting the Communist Party, and were against the king, joined the Partisans, also known as the Yugoslav National Liberation Army (NOV), led by Josip Broz Tito.

For every soldier killed, the Germans executed 100 civilians, and for each wounded, they killed 50. Regarding the human cost as too high, the Chetniks terminated war activities against the Germans, and the Allies eventually switched to support the NOV, which carried on its guerrilla warfare. The Yugoslav death toll was estimated at between 1,027,000 and 1,700,000. Very high losses were among Serbs who lived in Bosnia and Croatia, as well as Jewish and Roma minorities, high also among all other non-collaborating population.

During the war, the communist-led partisans were de facto rulers on the liberated territories, and the NOV organized people's committees to act as civilian government.

The Second Yugoslavia

Democratic Federal Yugoslavia was constituted at the Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia) conference in Jajce, Bosnia-Herzegovina (November 29 - December 4, 1943, while negotiations with the royal government in exile continued. On November 29, 1945, the Federative People's Republic of Yugoslavia was established as a communist state during the first meeting of democratically established and Communist-led Parliament in Belgrade.

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, formed on January 31, 1946, covered the same territory as its predecessor, plus land acquired from Italy in Istria and Dalmatia. The kingdom was replaced by a federation of six Socialist Republics, a Socialist Autonomous Province, and a Socialist Autonomous District that were part of the Socialist Republic of Serbia. The federation was modeled on the Soviet Union, and the federal capital was Belgrade. The six nominally equal socialist republics were: Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia. Serbia’s provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina were given autonomous status to take into account the interests of Albanians and Magyars, respectively.

On April 7, 1963, the official name was changed to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The first prime minister was Josip Broz Tito and president Ivan Ribar. In 1953, Tito was elected as president and later in 1974 named "President for life."

Government

This second Yugoslavia was at first highly centralized both politically and economically, with power held firmly by Tito's Communist Party of Yugoslavia and a constitution closely modeled on that of the Soviet Union. There were three levels of government: the federation, the republics, and 500 communes (opŇ°tine), which were agents for the collection of government revenue, and provided social services.

In 1988, there were about 90 political parties operating country-wide including the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, of which there were 2,079,013 party members. After Tito's death in 1980, the presidency rotated among regional representatives.

Tito was the most powerful person in the country, followed by republican and provincial premiers and presidents, and Communist Party presidents. A wide variety of people suffered from Tito's disfavor. Slobodan Penezińá Krcun, Tito's chief of secret police in Serbia, fell victim to a dubious traffic incident after he started to complain about Tito's politics. The Interior Minister Aleksandar Rankovińá lost his titles and rights after a disagreement with Tito regarding state politics. Sometimes ministers in government, such as Edvard Kardelj or Stane Dolanc, were more important than the prime minister.

The suppression of national identities escalated with the so-called Croatian Spring of 1970-1971, when students in Zagreb organized demonstrations for greater civil liberties and greater Croatian autonomy. The regime stifled the public protest and incarcerated the leaders, but many key Croatian representatives in the party silently supported this cause, so a new constitution was ratified in 1974 that gave more rights to the individual republics in Yugoslavia and provinces in Serbia.

Military

Much like the Kingdom of Yugoslavia that preceded it, the socialist Yugoslavia maintained a strong military force. The Yugoslav People's Army, or JNA, was the main military organization. The regular army mostly originated from the Yugoslav Partisans of the Second World War.

Once considered fourth largest in Europe, the JNA consisted of the ground forces, air force, and navy. They were organized in four military regions, each of which was divided into districts that were responsible for conscription, mobilization, and construction and maintenance of military facilities. The regions were: Belgrade (responsible for eastern Croatia, Serbia with Vojvodina and Bosnia and Herzegovina), Zagreb (Slovenia and northern Croatia), Skopje (Republic of Macedonia, southern Serbia and Montenegro) and Split Naval Region. Of the JNA's 180,000 soldiers, more than 100,000 were conscripts.

Most of its military equipment was domestically produced. Yugoslavia had a thriving arms industry and sold to Kuwait, Iraq, Myanmar, among others. Yugoslav companies like Zastava Arms would reproduce Soviet design weaponry under license as well as create weaponry from scratch. SOKO aircraft was an example of a successful design by Yugoslavia before the Yugoslav wars.

Economy

The economy of Yugoslavia was much different from economies of the Soviet Union and other Eastern European socialist countries. The occupation and liberation struggle in World War II left Yugoslavia's infrastructure devastated. Even the most developed parts of the country were largely rural and the little industry the country had was largely damaged or destroyed.

The communist government nationalized landholdings, industrial enterprises, public utilities, set up a central planning apparatus, and embarked on industrialization. Tito forced the collectivization of peasant agriculture (which failed by 1953). Despite this Soviet-style dictatorship, relations with the Soviet Union turned bitter, and in June 1948, Yugoslavia was expelled from the Communist Information Bureau and boycotted by the socialist countries.

Worker self-management

In the 1950s, worker self-management was introduced, reducing state control of the economy. Managers of socially owned companies were supervised by worker councils, which were made up of all employees, with one vote each. The worker councils appointed the management, often by secret ballot. The Communist Party was organized in all companies and the most influential employees were likely to be members of the party, so the managers were often, but not always, appointed only with the consent of the party.

With the exception of a recession in mid-1960s, the country's economy prospered formidably. Unemployment was low and the education level of the working force steadily increased. Due to Yugoslavia's neutrality and a leading role in the Non-aligned Movement, Yugoslav companies exported to both Western and Eastern markets. Yugoslav companies carried out construction of numerous major infrastructural and industrial projects in Africa, Europe and Asia.

Associated labor reorganization

In the 1970s, the economy was reorganized according to Edvard Kardelj's theory of associated labor, in which the right to decision making and a share in profits of socially owned companies is based on the investment of labor. All companies were transformed into "organizations of associated labor." The smallest "basic organizations of associated labor" roughly corresponded to a small company or a department in a large company. These were organized into "enterprises" also known as "labor organizations," which in turn associated into "composite organizations of associated labor," which could be large companies or even whole industry branches in a certain area. Most executive decision-making was based in enterprises, so that these continued to compete to an extent even when they were part of a same composite organization. The appointment of managers and strategic policy of composite organizations were, depending on their size and importance, in practice often subject to political and personal influence-peddling.

In order to give all employees the same access to decision making, the system was introduced into public services, including health and education. The basic organizations were usually made up of just dozens of people and had their own workers' councils, whose assent was needed for strategic decisions and appointment of managers in enterprises or public institutions.

The workers were organized into trade unions which spanned across the country. Strikes could be called by any worker, or any group of workers, and they were common in certain periods. Strikes for clear genuine grievances with no political motivation usually resulted in prompt replacement of the management and an increase in pay or benefits. Strikes with real or implied political motivation were often dealt with in the same manner (individuals were prosecuted or persecuted separately), but occasionally also met stubborn refusal to deal or in some cases brutal force. Strikes became increasingly common in the 1980s, when consecutive governments tried to salvage the slumping economy with a program of austerity under the auspices of the International Monetary Fund.

Oil crisis

During and after the oil crisis of the 1970s, Yugoslavia's foreign debt grew massively and by early 1980s it reached more than US$20-billion. The governments of Milka Planinc and Branko Mikulic renegotiated the foreign debt at the price of introducing the policy of "stabilization," which in practice consisted of severe austerity measures‚ÄĒthe so called "shock therapy economics." During the 1980s, the Yugoslav population endured fuel limitations (40 liters per car per month), car use limited to three days a week, based on the last digit on the license plate, limited imports of goods, and travelers were required to pay a deposit upon leaving the country (mostly to go shopping), to be returned in a year. With rising inflation, this amounted to a travel tax. There were shortages of coffee, chocolate and washing powder. During several dry summers, the government, unable to borrow to import electricity, was forced to cut power.

Collapse

Yugoslavia was once a regional industrial power and economic success. Two decades before 1980, annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 6.1 percent, medical care was free, literacy was 91 percent, and life expectancy was 72 years. The state provided housing, health care, education, and child care. Citizens lived well on a per capita income of $3000 a year (in 1980 dollars), with one month paid vacation, plus a year's maternity leave, if needed. Respect for workers was a central concern of government and society. But after a decade of Western economic ministrations and five years of disintegration, war, boycott, and embargo, the economy of the former Yugoslavia collapsed.

The Reagan administration of the United States targeted the Yugoslav economy. A 1984 National Security Decision Directive (NSDD 133) advocated "expanded efforts to promote a 'quiet revolution' to overthrow Communist governments and parties," while reintegrating the countries of Eastern Europe into a market-oriented economy.[1] Western trade barriers dramatically reduced Yugoslavia’s economic growth. In order to counter this, Yugoslavia took on a number of International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans and subsequently fell into heavy IMF debt. As a condition of receiving loans, the IMF demanded "market liberalization" of Yugoslavia. By 1981, Yugoslavia had incurred $19.9-billion in foreign debt. However, Yugoslavia’s real concern was the unemployment rate, at one million by 1980.

In 1989, before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Yugoslav federal Premier Ante Markovic went to Washington,, DC to meet President George Herbert Walker Bush, to negotiate a new financial aid package. In return for help, Yugoslavia agreed to even more sweeping economic reforms, including a new devalued currency, another wage freeze, sharp cuts in government spending, and the elimination of socially owned, worker-managed companies.[2] Rising inflation coincided with the spectacular draining of the banking system, in which millions of people were effectively forgiven debts or even allowed to make fortunes on perfectly legal bank-milking schemes, involving the use of cheques. Repayments of debts for privately owned housing, which was massively built during the prosperous 1970s, became ridiculously small and banks suffered huge losses.

On New Year's Eve 1989, Ante Markovińá introduced his program of economic reforms. Ten thousand dinars became one new dinar, pegged to the German mark at the rate of seven new dinars for one mark. The sudden end of inflation brought some relief to the banks. Ownership and exchange of foreign currency was deregulated, which, combined with a realistic exchange rate, attracted foreign currency to the banks. In the late 1980s, it was becoming increasingly clear that the federal government was effectively losing the power to implement its program.

In the 1990s, IMF effectively controlled the Yugoslav central bank. Its tight money policy further crippled the country's ability to finance its economic and social programs. State revenues that should have gone as transfer payments to the republics and provinces went instead to service Belgrade's debt with the Paris and London clubs. The republics were left on their own to survive. From 1989 through September 1990, more than one thousand companies went into bankruptcy. By 1990, the annual GDP growth rate had collapsed to a negative 7.5 percent. In 1991, GDP declined by a further 15 percent, while industrial output shrank by 21 percent.

The reforms demanded by Belgrade's creditors struck at the core of Yugoslavia's system of socially-owned and worker-managed enterprises. The objective of the reforms was to privatize Yugoslav economy and to dismantle the public sector. Yugoslavia was desperate and could not refuse their demand. With external pressure, Markovic's government passed legislation stating that if a business was unable to pay its bills for 30 days running, or for 30 days within a 45-day period, the government would launch bankruptcy proceedings.

In 1989, 248 firms were declared bankrupt or were liquidated and 89,400 workers were laid off. During the first nine months of 1990, another 889 enterprises with a combined work-force of 525,000 workers suffered the same fate. The total industrial workforce was 2.7 million. A further 20 percent of the work force, or half a million people, were not paid wages during the early months of 1990 as enterprises sought to avoid bankruptcy. The largest concentrations of bankrupt firms and lay-offs were in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republic of Macedonia and Kosovo. Real earnings were in a free fall and social programs had collapsed, creating within the population an atmosphere of despair‚ÄĒa critical turning point in the Yugoslav tragedy.

Ethnic tensions and the economic crisis

After Tito's death on May 4, 1980, ethnic tensions grew in Yugoslavia. The constitution of 1974 paralyzed the system of decision-making, made all the more hopeless as the conflict of interests had become irreconcilable. In the spring of 1990, Markovińá was supported by 83 percent of the population in Croatia, by 81 percent in Serbia, 59 percent in Slovenia, and by 79 percent in Yugoslavia as a whole. But Markovińá had coupled his Yugoslavism with the IMF "Shock therapy (economics)" program, giving the separatists in the northwest and the nationalists in Serbia their opening. The appeal of the separatists in Slovenia and Croatia involved offering to repudiate the Markovińá-IMF austerity thereby helping their republics to "join Europe." The appeal of Slobodan MiloŇ°evińá in Serbia was based around the idea that the West was acting against the Serbian people's interests. These nationalist appeals were ultimately successful.

The end of the Second Yugoslavia

Various dates are considered as the end of the Second Yugoslavia:

- June 25, 1991, when Croatia and Slovenia declared independence

- September 8, 1991, when Macedonia declared independence

- October 8, 1991, when the July 9 moratorium on Slovenian and Croatian secession was ended and Croatia restated its independence in the Croatian parliament (that day is celebrated as Independence Day in Croatia)

- January 15, 1992, when Slovenia and Croatia were internationally recognized by most European countries

- April 6, 1992, full recognition of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s independence by the United States and most European countries

- April 28, 1992, the formation of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Serbia’s influence reduced

The largest Yugoslav republic in territory and population, Serbia's influence over the regions of Kosovo and Vojvodina was reduced by the 1974 constitution. Because its two autonomous provinces had de facto prerogatives of full-fledged republics, Serbia found that its hands were tied, for the republican government was restricted in making and carrying out decisions that would apply to the provinces. Since the provinces had a vote in the Federal Presidency Council (an eight-member council composed of representatives from six republics and two autonomous provinces), they sometimes even entered into coalition with other republics, thus outvoting Serbia. Serbia's political impotence made it possible for others to exert pressure on the two million Serbs (20 percent of total Serbian population) living outside Serbia.

MiloŇ°evic

The Serbian government feared multiparty democracy would split Yugoslavia. Slobodan MiloŇ°evic (1941-2006), a former business official, who from 1986 rose to power through the League of Communists of Serbia, emerged in April 1987 as the leading force in Serbian politics. He became president of the Serbian Republic on May 8, 1989. When Serbia was compelled to hold multiparty elections in December 1990, the League of Communists was renamed the Socialist Party of Serbia, and leader MiloŇ°evic ensured that no opposition could emerge. His party won a large majority in the Skupstina.

MiloŇ°evińá sought to restore pre-1974 Serbian sovereignty. Other republics, especially Slovenia and Croatia, denounced this move as a revival of great Serbian hegemonism. MiloŇ°evińá succeeded in reducing the autonomy of Vojvodina and of Kosovo and Metohija, but both entities retained a vote in the Yugoslav Presidency Council. The very instrument that reduced Serbian influence before was now used to increase it: in the eight-member Council, Serbia could now count on four votes minimum - Serbia proper, then-loyal Montenegro, and Vojvodina and Kosovo.

Communist Party dissolved

In January 1990, the extraordinary 14th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia was convened. The Slovenian and Serbian delegations were arguing over the future of the League of Communists and Yugoslavia. The Serbian delegation, led by MiloŇ°evińá, insisted on a policy of "one person, one vote," which would empower the majority population, the Serbs. In turn, the Slovenes, supported by Croats, sought to reform Yugoslavia by devolving even more power to republics, but were voted down. As a result, the Slovenian, and eventually Croatian delegation left the congress, and the all-Yugoslav Communist party was dissolved.

Following the fall of communism in the rest of Eastern Europe, each of the republics held multi-party elections in 1990. Slovenia and Croatia held the elections in April, electing governments oriented towards greater autonomy of the republics (under Milan Kuńćan and Franjo TuńĎman, respectively). Serbia held parliamentary elections which confirmed (former) communist rule in their republic. Serbia and Montenegro elected candidates who favored Yugoslav unity.

Serbian uprisings in Croatia

The Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) was formed, and Franjo Tudjman, a former general in Tito's World War II anti-fascist Yugoslav Partisan movement, rose to power. In 1990, the first free elections were held in Slovenia and Croatia. The Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), led by TuńĎman, won by a slim margin against the reformed communist Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP), and Ivica Rańćan, the former president of Croatia's branch of the Yugoslav Communist's League. Tudman‚Äôs party wanted more independence for Croatia, contrary to the wishes of ethnic Serbs in the republic and official politics in Belgrade.

Serbs in Croatia wouldn't accept a status of a national minority in a sovereign Croatia since Serbs considered Yugoslavia as a whole as their realm. Serbian uprisings in Croatia began in August 1990 by blocking roads leading from the Dalmatian coast towards the inland almost a year before Croatian leadership made any move towards independence. The Serbs proclaimed the emergence of Serbian Autonomous Areas (known later as Republic of Serb Krajina) in Croatia.

The Yugoslav People's Army, mainly consisting of Serbs, blocked intervention by Croatian police. Slovenia and Croatia began illegally importing arms. In March 1990, during the demonstrations in Split (Croatia), a young Yugoslav conscript was pushed off a tank after driving it through a crowd of people. Guns were fired from army bases through Croatia. Elsewhere, tensions were running high.

In the same month, the Yugoslav People's Army met the president of Yugoslavia seeking a declaration of a state of emergency, which would allow the army to take control. The representatives of Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo and Metohija, and Vojvodina voted for the decision, while all other republics, Croatia, Slovenia , Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, voted against. The tie delayed an escalation of conflicts.

The republics of Slovenia and Croatia proposed transforming Yugoslavia into a loose confederation of six republics in the autumn of 1990, however Slobodan MiloŇ°evińá rejected all such proposals, arguing that like Slovenes and Croats, the Serbs should also have a right to self-determination.

Croatia, Slovenia independent

On June 25, 1991, Slovenia and Croatia became the first republics to declare independence from Yugoslavia. The following day (June 26), the Federal Executive Council specifically ordered the army to take control of the "internationally recognized borders." The resulting Ten-Day War was a brief military conflict between Slovenia and Yugoslavia in 1991 following Slovenia's declaration of independence.

Croatian war of independence

When Croatia declared independence on June 25, 1991, the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) attacked Croatian cities, notably Vukovar and Dubrovnik. Civilians fled‚ÄĒthousands of Croats moved away from the Bosnian and Serbian border, while thousands of Serbs moved towards it. The Croatian Parliament cut remaining ties with Yugoslavia on October 8, 1991. At the end of 1991 there was full-scale war in Croatia.

The Yugoslav People's Army, which consisted mostly of conscripts from Serbia and Montenegro, and irregulars from Serbia, forced masses of civilians out of areas in what became known as "ethnic cleansing." Ethnic Serbs in Croatian-dominated areas of Croatia were similarly forced out by the Croatian army and irregular forces. A war of words harked back to atrocities committed during World War II. Serbs used the term "Ustasha" as a negative term to refer to any Croat, and Croats called Serbs "Chetniks."

The border city of Vukovar underwent a three-month siege‚ÄĒthe Battle of Vukovar‚ÄĒduring which most of the city was destroyed and most inhabitants were forced to flee. The city fell to the Serbian forces on November 18, 1991. Subsequent United Nations-sponsored cease-fires followed. The Yugoslav People's Army retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina where the Bosnian War was just about to start. During 1992 and 1993, Croatia handled an estimated 700,000 refugees from Bosnia, mainly Bosnian Muslims.

Armed conflict in Croatia remained intermittent and mostly on a small scale until 1995. In early August, Croatia started Operation Storm and quickly reconquered most of the territories of the Republic of Serbian Krajina, leading to an exodus of the Serbian population. An estimated 90,000-350,000 Serbs fled. A few months later, the war ended with the negotiation of the Dayton Agreement. A peaceful integration of the remaining Serbian-controlled territories in Eastern Slavonia was completed in 1998 under U.N. supervision. The Serbs who fled from the former Krajina had not returned by 2007.

Macedonia independent

In September 1991, the Republic of Macedonia also declared independence, becoming the only former republic to gain sovereignty without resistance from the Belgrade-based Yugoslav authorities. Five hundred U.S. soldiers were then deployed under the U.N. banner to monitor Macedonia's northern borders with the Republic of Serbia, Yugoslavia. Macedonia's first president, Kiro Gligorov, maintained good relations with Belgrade.

Ethnic rift in Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina has historically been a multi-ethnic state. In 1990, its population included approximately 43 percent of Bosniaks, 31 percent of Serbs, and 17 percent of Croats. On the first multi-party elections that took place in November 1990 in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the three largest ethnic parties in the country won: the Bosniak Party of Democratic Action, the Serbian Democratic Party and the Croatian Democratic Union. They formed a coalition government. Power was divided along the ethnic lines so that the president of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was a Bosniak, president of the parliament was a Bosnian Serb and the prime minister a Croat.

But the Serb members of parliament, consisting mainly of the Serb Democratic Party members, but also including some other party representatives (which would form the "Independent Members of Parliament Caucus"), abandoned the central parliament in Sarajevo, and formed the Assembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina on October 24, 1991, which marked the end of the tri-ethnic coalition.

The ruling party in the Republic of Croatia, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), organized and controlled the branch of the party in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina (HDZBiH). By the latter part of 1991, the more extreme elements of the HDZBiH, under the leadership of Mate Boban, Dario Kordińá and others, with the support of Franjo TuńĎman and Gojko ҆uŇ°ak, had taken effective control of the party. On November 18, 1991, the extreme elements of the HDZBiH, led by Mate Boban and Dario Kordińá later convicted by ICTY of war crimes, proclaimed the existence of the "Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia," as a separate "political, cultural, economic and territorial whole," on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

After Slovenia and Croatia declared independence from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Bosnia and Herzegovina organized a referendum on independence‚ÄĒin November 1991. This resulted in an overwhelming vote in favor of staying in a common state with Serbia and Montenegro. On January 9, 1992, the self-proclaimed Bosnian Serb assembly proclaimed a separate "Republic of the Serb people of Bosnia and Herzegovina." The referendum and creation of the republic were declared illegal and invalid by the government of Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, in February-March 1992 the government held a national referendum on Bosnian independence. That referendum was in turn declared unconstitutional; it was largely boycotted by the Bosnian Serbs. The Bosnia and Herzegovina‚Äôs government declared its independence on April 5, and the Serbs immediately declared the independence of Republika Srpska. The war in Bosnia followed shortly thereafter.

The Third Yugoslavia

The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (–°–į–≤–Ķ–∑–Ĺ–į –†–Ķ–Ņ—É–Ī–Ľ–ł–ļ–į –ą—É–≥–ĺ—Ā–Ľ–į–≤–ł—ė–į / Savezna Republika Jugoslavija), also referred to as the Third Yugoslavia, was a federal state consisting of the republics of Serbia and Montenegro that existed from April 28, 1992, to February 4, 2003, when it was reconstituted as a State Union of Serbia and Montenegro.

After Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia broke away from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and amid civil war, the remaining republics of Serbia and Montenegro reconstituted the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia on April 28, 1992.

A new constitution, adopted on April 27, 1992, created a federal government consisting of a bicameral legislative assembly, a president elected by the assembly, a prime minister nominated by the president and approved by the assembly, a federal court, a state prosecutor, and a national bank. The republics controlled social and economic affairs, while the federal government controlled defense and security, foreign policy, the monetary system, human and civil rights, and communications. Serbia and Montenegro had separate governments under separate constitutions.

Unlike its predecessor, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was far more ethnically homogeneous. The state's two largest ethnic groups, Serbs and Montenegrins, were almost ethnically identical, though nationalist strains amongst Montenegrins claim that they constitute an ethnic derivative of their own, while others, especially those who support union with Serbia claim that Montenegrins are a sub-group of Serbs. Ethnic minorities included Albanians, Hungarians, Romanians, and other smaller groups. Ethnic tensions between Serbs and ethnic Albanians in the province of Kosovo was a serious and ongoing problem in the FRY throughout its existence.

The United Nations and many individual states, especially the United States, accepted it as constituting a state, but refused to recognize it (or the other republics) as a successor of the former Yugoslavia. The FRY was regarded as being Serbia, as it was dominated by Serbia, while Montenegro contributed little in international political affairs involving the FRY.

The FRY was suspended from a number of international institutions, as a result of the ongoing Yugoslav wars during the 1990s, which had prevented agreement being reached on the disposition of federal assets and liabilities, particularly the national debt. Because the Government of Yugoslavia supported Croatian and Bosnian Serbs in the Yugoslav wars from 1991 to 1995, the country was under economical and political sanctions, which resulted in economical disaster that forced thousands of its young citizens to emigrate from the country.

War in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The War in Bosnia and Herzegovina, commonly known as the Bosnian War, was an international armed conflict that took place between March 1992 and November 1995. The war involved several sides. According to the numerous International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) judgements the conflict was between Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (later Serbia and Montenegro) and [[Bosnia and Herzegovina|Bosnia. According to International Court of Justice judgment, Serbia gave military and financial support to Serb forces which consisted of Yugoslav People's Army (later Army of Serbia and Montenegro), Army of Republika Srpska, Serbian Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of the Interior of Republika Srpska and Serb Territorial Defense Forces. Croatia gave military support to Croat forces of Herzeg-Bosnia. Bosnian government forces were led by Army of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. These factions changed their objectives and allegiances several times at various stages of the war. Most Bosniaks and many Croats claimed that the war was a war of aggression from Serbia, while Serbs mostly considered it a civil war.

The involvement of NATO, during the 1995 Operation Deliberate Force against the positions of the Army of Republika Srpska made the war an international conflict, but only in its final stages. The war was brought to an end after the signing of the Dayton Agreement in Paris on December 14, 1995. The peace negotiations were held in Dayton, Ohio, and were finalized on December 21, 1995.

The death toll after the war was originally estimated at around 200,000 by the Bosnian government. They also recorded around 1,326,000 refugees and exiles. Research done by Tibeau and Bijak in 2004 determined a number of 102,000 deaths and estimated the following breakdown: 55,261 were civilians and 47,360 were soldiers. Of the civilians: 16,700 were Serbs while 38,000 were Bosniaks and Croats. Of the soldiers, 14,000 were Serbs, 6,000 were Croats, and 28,000 were Bosniaks. On June 21, 2007, the Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo published the most extensive research on Bosnia-Herzegovina's war casualties titled: The Bosnian Book of the Dead - a database that reveals 97,207 names of Bosnia and Herzegovina's citizens killed and missing during the 1992-1995 war. An international team of experts evaluated the findings before they were released. Of the 97,207 documented casualties in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 83 percent of civilian victims were Bosniaks, 10 percent of civilian victims were Serbs and more than 5 percent of civilian victims were Croats, followed by a small number of others such as Albanians or Romani people. The percentage of Bosniak victims would be higher had survivors of Srebrenica not reported their loved-ones as 'soldiers' to access social services and other government benefits.

Ethnic cleansing was a common phenomenon in the war. This typically entailed intimidation, forced expulsion and/or killing of the undesired ethnic group as well as the destruction or removal of the physical vestiges of the ethnic group, such as places of worship, cemeteries and cultural and historical buildings. According to Dario Kordińá and Radoslav BrńĎanin judgements in ICTY,[3] Serb and Croat forces performed ethnic cleansing of their territories. Serb forces also committed genocide in Srebrenica. Bosniak-controlled Sarajevo saw a fraction of its Serb and Croat population remain, as well as Tuzla in the northeast of the country. Currently, Croats do not inhabit Posavina, Serbs are not in parts of Bosanska Krajina, while many Bosniaks did not return to many urban areas in the today's Republika Srpska.

Kosovo conflict

The term ‚ÄúKosovo Conflict‚ÄĚ is often used to describe two sequential and at times parallel armed conflicts in Kosovo. These conflicts were:

- 1996‚Äď1999: Conflict between Serbian and Yugoslav security forces and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), an ethnic Albanian guerrilla group seeking secession from the former Yugoslavia.

- 1999: War between Yugoslavia and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization between March 24 and June 10, 1999, during which NATO attacked Yugoslav targets, Albanian guerrillas continued battles with Yugoslav forces, amidst a massive displacement of population in Kosovo.

The Communist government of Josip Broz Tito systematically repressed nationalist manifestations throughout Yugoslavia, seeking to ensure that no Yugoslav republic or nationality gained dominance over the others. In particular, the power of Serbia‚ÄĒthe largest and most populous republic‚ÄĒwas diluted by the establishment of autonomous governments in the province of Vojvodina in the north of Serbia and Kosovo in the south. The Muslim Albanians of Kosovo always resisted the ambition of a Yugoslav identity. A revolt had broken out in 1945 in UroŇ°evac in support of the unification of Kosovo with Albania. Thousands of Albanian Muslims were deported to Turkey. From then, the Kosovo problem was contained rather than solved, and containment repeatedly broke down in disorder in 1968, 1981, 1989, and 1998‚Äď1999.

A controversial SANU Memorandum, leaked from prominent members of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts in September, 1986, paid special attention to Kosovo, arguing that the province's Serbs were being subjected to genocide, and called for action by Serbia to protect Serbs in Kosovo. In November 1988, Kosovo's head of the provincial committee was arrested. In March 1989, MiloŇ°evińá announced an "anti-bureaucratic revolution" in Kosovo and Vojvodina, curtailing their autonomy and imposing a curfew and a state of emergency in Kosovo due to violent demonstrations,

In 1989, Ibrahim Rugova, the leader of the Kosovo Albanians, had launched a non-violent protest against the loss of provincial autonomy. When the autonomy question was not addressed in the Dayton Accords, the Kosovo Liberation Army emerged during 1996. Sporadic attacks on police escalated by 1998 to a substantial armed uprising, which provoked a Serbian attack that resulted in massacres and massive expulsions of ethnic Albanians living in Kosovo.

British Prime Minister Tony Blair wrote in an article published by the BBC on May 14, 1999, that "It is no exaggeration to say what is happening in Kosovo is racial genocide. No exaggeration to brand the behaviour of Milosevic's forces as evil. It is something we had hoped we would never experience again in Europe. Thousands murdered. One hundred thousand men missing. Hundreds of thousands of people forced to flee their homes and their country, robbed of anything of value at gun-point."[4]

The MiloŇ°evic government's rejection of a proposed settlement led to NATO's bombing of Serbia in the spring of 1999, and to the eventual withdrawal of Serbian military and police forces from Kosovo in June 1999. A United Nations Security Council resolution (1244) in June 1999 authorized the stationing of a NATO-led force (KFOR) in Kosovo to provide a safe environment for the region's ethnic communities, created a UN Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) to foster self-governing institutions, and reserved the issue of Kosovo's final status for an unspecified date in the future.

NATO acknowledged killing at most 1500 civilians. Human Rights Watch counted a minimum of 488 civilian deaths (90 to 150 of them killed from cluster bomb use) in 90 separate incidents. The exact number of Albanian civilians killed is unclear. Some mass graves were also found in Serbia itself, on Yugoslav military bases or dumped in the Danube River. The total number of Albanian dead is generally claimed to be around 10,000 although several foreign forensic teams were unable to verify the exact number. There were up to 5000 Yugoslav military casualties according to NATO estimates, while the Yugoslav authorities claim 169 soldiers were killed and 299 wounded.

MiloŇ°evic goes

MiloŇ°evic and the SPS retained power despite huge opposition in November 1996 elections, although the government conceded that there had been large-scale electoral fraud, provoking months of demonstrations. In July 1997 MiloŇ°evic, barred by the constitution from service as Serbia's president, engineered his election to the federal presidency, and went on to clash with the leadership of Montenegro. MiloŇ°evińá's rejection of claims of a first-round opposition victory in new elections for the federal presidency in September 2000 led to mass demonstrations in Belgrade on October 5 and the collapse of the regime's authority. The opposition's candidate, Vojislav KoŇ°tunica took office as Yugoslav president on October 6, 2000.

Following parliamentary elections in January 2001, Zoran ńźinńĎińá became prime minister. ńźinńĎińá was assassinated in Belgrade on March 12, 2003. A state of emergency was declared under acting president NataŇ°a Mińáińá.

On Saturday, March 31, 2001, MiloŇ°evińá surrendered to Yugoslav security forces from his home in Belgrade, following a warrant for his arrest on charges of abuse of power and corruption. His trial on charges of genocide in Bosnia and war crimes in Croatia and in Kosovo and Metohija began at The Hague on February 12, 2002. He died there on March 11, 2006, while his trial was still ongoing. On April 11, 2002, the Yugoslav parliament passed a law allowing extradition of all persons charged with war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal.

Economy halved

Mismanagement of the economy, an extended period of economic sanctions, and the damage to Yugoslavia's infrastructure and industry caused by war left the economy only half the size it was in 1990. Since the ousting of former MiloŇ°evińá in October 2000, the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS) coalition government implemented stabilization measures and embarked on an aggressive market reform program. After renewing its membership in the International Monetary Fund in December 2000, Yugoslavia continued to reintegrate into the international community by rejoining the World Bank (IBRD) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

End of Yugoslavia

In 2002, Serbia and Montenegro came to a new agreement regarding continued co-operation, which, among other changes, promised the end of the name Yugoslavia, since they were part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. On February 4, 2003, the federal parliament of Yugoslavia created a loose confederation - State Union of Serbia and Montenegro. A new constitutional charter was agreed to provide a framework for the governance of the country.

On Sunday, May 21, 2006, Montenegrins voted on independence in a referendum, with 55.5 percent supporting independence. Fifty-five percent or more of affirmative votes were needed to dissolve the state union of Serbia and Montenegro. The turnout was 86.3 percent and 99.73 percent of the more than 477,000 votes cast were deemed valid.

The subsequent Montenegrin proclamation of independence on June 3, 2006, and the Serbian proclamation of independence on June 5 ended the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro and thus the last remaining vestiges of the former Yugoslavia.

New Nations

The countries created from the former parts of Yugoslavia are:

The first former Yugoslav republic to join the European Union was Slovenia, which applied in 1996 and became a member in 2004. Croatia applied for membership in 2003, and could join before 2010. Republic of Macedonia applied in 2004, and will probably join by 2010‚Äď2015. The remaining three republics have yet to apply so their acceptance generally is not expected before 2015. These states are signatories of various partnership agreements with the European Union. Since January 1, 2007 they have been encircled by member-states of EU.

The Assembly of Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in February 2008. Its independence is recognized by 85 UN member states and the Republic of China (Taiwan). On October 8, 2008, upon request of Serbia, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution asking the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion on the issue of Kosovo's declaration of independence.[5] On 22 July 2010, the court ruled that Kosovo's independence was not illegal.[6]

The similarity of the languages and the long history of common life have left many ties among the peoples of the new nations, even though the individual state policies of the new states favor differentiation, particularly in language. The Serbo-Croatian language is linguistically a unique language, with several literary and spoken variants and also was the imposed means of communication used where other languages dominated (Slovenia, Macedonia and Kosovo). Now, separate sociolinguistic standards exist for Bosnian language, Croatian language and the Serbian language. SFRY technically had three official languages, along with minority languages official where minorities lived, but in all federal organs only Serbo-Croatian was used and others were expected to use it as well.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Sean Gervasi, 'Germany, the US, and the Yugorlav Crisis,' Covert Action 43 (Winter 1992-1993): 42

- ‚ÜĎ Gervasi, 44

- ‚ÜĎ United Nations, Radoslav BrńĎanin judgment (September 1, 2004). Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Tony Blair, UK Politics, Blair: My pledge to the refugees, BBC News (May 14, 1999). Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Louis Charbonneau, U.N. backs Serbia in judicial move on Kosovo Reuters (October 8, 2008). Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ Kosovo independence not illegal, says UN court BBC News (22 July 2010). Retrieved December 5, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allcock, John B. Explaining Yugoslavia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780231120555

- Cohen, Lenard J. Broken bonds: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1993. ISBN 9780813318547

- Dragnich, Alex N. Serbs and Croats: The Struggle in Yugoslavia. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992. ISBN 9780151810734

- Glenny, Misha. The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-1999. New York, NY: Viking, 2000. ISBN 9780670853380

- Glenny, Misha. The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War. London: Penguin, 1992. ISBN 9780140172881

- Gutman, Roy. A Witness to Genocide: The 1993 Pulitzer Prize-winning Dispatches on the "Ethnic Cleansing" of Bosnia. New York, NY: Macmillan Pub. Co., 1993. ISBN 9780020329954

- Hall, Brian. The Impossible Country: A Journey through the Last Days of Yugoslavia. Boston, MA: D.R. Godine, 1994. ISBN 9781567920000

- Lampe, John R. Yugoslavia as History: Twice there was a Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780521467056

External links

All links retrieved June 4, 2023.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica History of Yugoslavia, 1929-2003

- Countries of the World Yugoslavia (former) geographic.org.

- Break-up of Yugoslavia Timeline BBC News.

- WWW-VL: History: Yugoslavia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Yugoslavia  history

- Creation_of_Yugoslavia  history

- Serbia  history

- Croatia  history

- Bosnia_and_Herzegovina  history

- Economy_of_the_Socialist_Federal_Republic_of_Yugoslavia  history

- Demographics_of_the_Socialist_Federal_Republic_of_Yugoslavia  history

- Socialist_Federal_Republic_of_Yugoslavia  history

- Federal_Republic_of_Yugoslavia  history

- Croatian_War_of_Independence  history

- War_in_Bosnia_and_Herzegovina  history

- Kosovo_War  history

- Serbia_and_Montenegro  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.