Refugee

Refugee was defined as a legal group in response to the large numbers of people fleeing Eastern Europe following World War II. Under international law, refugees are individuals who are outside their country of nationality or habitual residence; have a well-founded fear of persecution because of their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion; and are unable or unwilling to avail themselves of the protection of that country, or to return there, for fear of persecution.

The lead international agency coordinating refugee protection is the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The major exception are the four million Palestinian refugees under the authority of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), who are the only group to be granted refugee status to the descendants of refugees.

When people must leave their homeland becoming refugees, there is always a terrible sense of loss, a deep suffering. When they are not welcomed, but must spend extended time in camps, this magnifies their suffering to almost unbearable levels with serious consequences for them and their children. In a world full of barriers between countries, races, religions, and so forth, refugees have become an ever increasing problem as conflicts have erupted. The problem of refugees will be solved when we break down these barriers and learn to live in peace and harmony as one human family.

Definition

According to the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees adopted in 1951, a refugee is defined as a person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of their nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail him/herself of the protection of that country.[1] The concept of a refugee was expanded by the Conventions’ 1967 Protocol and by regional conventions in Africa and Latin America to include persons who had fled war or other violence in their home country. A person who is seeking to be recognized as a refugee is an asylum seeker.

Refugees are a subgroup of the broader category of displaced persons. Environmental refugees (people displaced because of environmental problems such as drought) are not included in the definition of "refugee" under international law, as well as internally displaced people. According to international refugee law, a refugee is someone who seeks refuge in a foreign country because of war and violence, or out of fear of persecution "on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group."[2]

The practical determination of whether a person is a refugee or not is most often left to certain government agencies within the host country. This can lead to abuse in a country with a very restrictive official immigration policy; for example, that the country will neither recognize the refugee status of the asylum seekers nor see them as legitimate migrants and treat them as illegal aliens. Failed asylum applicants are most often deported, sometimes after imprisonment or detention.

A claim for asylum may also be made onshore, usually after making an unauthorized arrival. Some governments are relatively tolerant and accepting of onshore asylum claims; other governments will not only refuse such claims, but may actually arrest or detain those who attempt to seek asylum. A small number of governments, such as that of Australia, have a policy of mandatory detention of asylum seekers.

The term "refugee" is sometimes applied to people who may have fit the definition if the 1951 Convention was applied retroactively. There are many candidates. For example, after the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 outlawed Protestantism in France, hundreds of thousands of Huguenots fled to England, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway, Denmark, and Prussia.

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) reported in 2022 that there were over one hundred million people forced to flee conflict, violence, human rights violations, and persecution, including internally displaced persons, who remain within the same national borders.[3] The majority of refugees who leave their country seek asylum in countries neighboring their country of nationality. The "durable solutions" to refugee populations, as defined by UNHCR and governments, are: voluntary repatriation to the country of origin; local integration into the country of asylum; and resettlement to a third country. [4]

History

Before the nineteenth century, the right to asylum in another country was commonly recognized and people were able to travel from country to country without need of special identification, passports, or visas. Thus, although refugees moved in waves from region to region throughout history, there was no actual problem regarding refugees.

The exodus of groups for religious or racial reasons was quite common in history. Most notably the Jews, after losing their homeland, were forced to move from various places of settlement at various times. However, they were usually accepted into a new area and re-established themselves there, in diaspora. In more recent times, political refugees became a problem, becoming numerous particularly in the twentieth century following the rise of Communism. By this time borders were fixed, travel documents were required, and large numbers of refugees were often not welcome.

The division of territories also led to refugee movements. The partition of Germany after World War II and India in 1947 into Hindu and Muslim states led to millions of displaced persons. Similarly, the establishment of Israel in 1948 partitioned Palestine and resulted in the exodus of Palestinians into neighboring Arab nations. Equally, the dissolution of countries, such as former Yugoslavia, has led to significant population movements and refugee problems.

Africa has also become an area of large refugee problems, following various civil wars and revolutions. Conflicts in Asia, such as in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, have also produced significant numbers of refugees. Despite the efforts of refugee organizations, there have continued to be serious problems with the large numbers of refugees needing new homes.

Early history of refugee organizations

The concept of sanctuary, in the meaning that a person who fled into a holy place could not be harmed without inviting divine retribution, was understood by the ancient Greeks and ancient Egyptians. However, the right to seek asylum in a church or other holy place, was first codified in law by King Ethelbert of Kent in about 600 C.E. Similar laws were implemented throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. The related concept of political exile also has a long history: Ovid was sent to Tomis and Voltaire was exiled to England. However, it was not until late eighteenth century Europe that the concept of nationalism became prevalent enough that the phrase "country of nationality" became meaningful and people crossing borders were required to provide identification.

The first international coordination on refugee affairs was by the League of Nations' High Commission for Refugees. The Commission, led by Fridtjof Nansen, was set up in 1921 to assist the approximately one and a half million persons who fled the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent civil war (1917–1921), most of them aristocrats fleeing the Communist government. In 1923, the mandate of the Commission was expanded to include the more than one million Armenians who left Turkish Asia Minor in 1915 and 1923 due to a series of events now known as the Armenian Genocide. Over the next several years, the mandate was expanded to include Assyrians and Turkish refugees.[5] In all of these cases, a refugee was defined as a person in a group for which the League of Nations had approved a mandate, as opposed to a person to whom a general definition applied.

In 1930, the Nansen International Office for Refugees was established as a successor agency to the Commission. Its most notable achievement was the Nansen passport, a passport for refugees, for which it was awarded the 1938 Nobel Peace Prize. The Nansen Office was plagued by inadequate funding, rising numbers of refugees and the refusal by League members to let the Office assist their own citizens. Regardless, it managed to convince fourteen nations to sign the Refugee Convention of 1933, a weak human right instrument, and assist over one million refugees. The rise of Nazism led to such a severe rise in refugees from Germany that in 1933 the League created a High Commission for Refugees Coming from Germany. The mandate of this High Commission was subsequently expanded to include persons from Austria and Sudetenland. On December 31, 1938, both the Nansen Office and High Commission were dissolved and replaced by the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees under the Protection of the League.[5] This coincided with the flight of several hundred thousand Spanish Republicans to France after their loss to the Nationalists in 1939 in the Spanish Civil War.

Evolving refugee organizations

The conflict and political instability during World War II led to massive amounts of forced migration. In 1943, the Allies created the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) to provide aid to areas liberated from Axis powers, including parts of Europe and China. This included returning over seven million refugees, then commonly referred to as "displaced persons" or DPs, to their country of origin and setting up displaced persons camps for one million refugees who refused to be repatriated. Also, thousands of former Russian citizens were repatriated by force (against their will) into the USSR.[6]

After the defeat of Germany in World War II, the Potsdam Conference authorized the expulsion of German minorities from a number of European countries (including Soviet- and Polish-annexed pre-war east Germany), meaning that 12,000,000 ethnic Germans were displaced to the reallocated and divided territory of Allied-occupied Germany. Between the end of World War II and the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961, more than three million refugees from East Germany traveled to West Germany for asylum from the Soviet occupation.

The UNRRA was shut down in 1949 and its refugee tasks given to the International Refugee Organization (IRO). The IRO was a temporary organization of the United Nations (UN), which itself had been founded in 1945, with a mandate to largely finish the UNRRA's work of repatriating or resettling European refugees. It was dissolved in 1952 after resettling about one million refugees. The definition of a refugee at this time was an individual with either a Nansen passport or a "Certificate of Eligibility" issued by the International Refugee Organization.

Rise of the UNHCR

Headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (established December 14, 1950) protects and supports refugees at the request of a government or the United Nations and assists in their return or resettlement. It succeeded the earlier International Refugee Organization and the even earlier United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (which itself succeeded the League of Nations' Commissions for Refugees).

UNHCR provides protection and assistance not only to refugees, but also to other categories of displaced or needy people. These include asylum seekers, refugees who have returned home but still need help in rebuilding their lives, local civilian communities directly affected by the movements of refugees, stateless people, and so-called internally displaced people (IDPs). IDPs are civilians who have been forced to flee their homes, but who have not reached a neighboring country and therefore, unlike refugees, are not protected by international law and may find it hard to receive any form of assistance.

UNHCR was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1954 and 1981. The agency is mandated to lead and co-ordinate international action to protect refugees and resolve refugee problems worldwide. Its primary purpose is to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees. It strives to ensure that everyone can exercise the right to seek asylum and find safe refuge in another State, with the option to return home voluntarily, integrate locally or to resettle in a third country.

UNHCR's mandate has gradually been expanded to include protecting and providing humanitarian assistance to what it describes as other persons "of concern," including internally-displaced persons (IDPs) who would fit the legal definition of a refugee under the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol, the 1969 Organization for African Unity Convention, or some other treaty if they left their country, but who presently remain in their country of origin. UNHCR thus has missions in Colombia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Serbia and Montenegro, and Côte d'Ivoire to assist and provide services to IDPs.

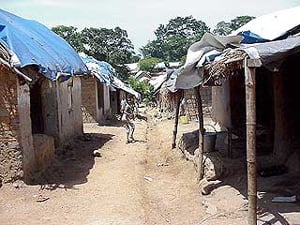

Refugee camps

A refugee camp is a place built by governments or NGOs (such as the ICRC) to receive refugees. People may stay in these camps, receiving emergency food and medical aid, until it is safe to return to their homes. In some cases, often after several years, other countries decide it will never be safe to return these people, and they are resettled in "third countries," away from the border they crossed.

Unfortunately, many times, refugees are not resettled. Rather, they are kept in the camps and denied permission to live as citizens in the country where the camp is located. They may be arrested and deported to their native countries if they stray too far. Such camps become the breeding ground for disease, child soldiering, terrorist recruitment, and physical and sexual violence.

Middle-East

Palestinian refugees

Following the 1948 proclamation of the State of Israel, the first Arab-Israeli War began. Many Palestinians had already become refugees, and the Palestinian Exodus (Nakba) continued through the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and after the armistice that ended it. The great majority have remained refugees for generations as they were not permitted to return to their homes or to settle in the Arab countries where they lived. The refugee situation with the presence of numerous refugee camps continues to be a point of contention in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The final estimate of refugee numbers was over seven hundred thousand according to the United Nations Conciliation Commission. Palestinian refugees from 1948 and their descendants do not come under the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, but under the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, which created its own criteria for refugee classification. As such they are the only refugee population legally defined to include descendants of refugees, as well as others who might otherwise be considered internally displaced persons.

Jewish refugees

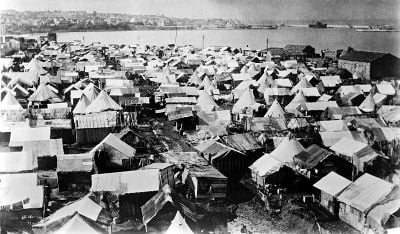

In Europe, the Nazi persecution culminated in the Holocaust of European Jews. The Bermuda Conference, Evian Conference, and other attempts failed to resolve the problem of Jewish refugees from Europe. Between the two wars, Jewish immigration to Palestine was encouraged by the nascent zionist movement, but severely restricted by the British mandate government in Palestine. Soon after the establishment of Israel in 1948, the state adopted the law of return granting Israeli citizenship to any Jew immigrant. With the gates of Palestine now opened, some seven hundred thousand refugees flooded this small, young country at a time of war. This human flood was housed in tent cities called Ma'abarot. More recently, following the dissolution of the USSR, a second surge of seven hundred thousand Russian Jews fled to Israel between 1990 and 1995.

Jews lived in what are now Arab states at least since the Babylonian captivity (597 B.C.E.). In 1945, there were about eight hundred thousand Jews living in communities throughout the Arab world. After the creation of the state of Israel and the 1948 Arab-Israeli War that ensued, conditions for Jews in the Arab world deteriorated. The situation worsened following the 1967 Six-Day War. Over the next few decades, most would leave the Arab world, nearly six hundred thousand, most finding refuge in Israel. Today, in all the Arab countries except Morocco, the Jewish population has disappeared or shrunk below survival levels.

Iraq

The situation in Iraq at the beginning of the twenty-first century has generated millions of refugees and internally displaced persons. According to the UNHCR, as of April 2007, nearly two million Iraqis have been forced to flee their country, most to Syria and Jordan, and close to two million others are displaced internally.

The Iran-Iraq war from 1980 to 1988, the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the first Gulf War and subsequent conflicts all generated hundreds of thousands if not millions of refugees. Iran also provided asylum for over one million Iraqi refugees who had been uprooted as a result of the Persian Gulf War (1990–1991).

Asia

Afghanistan

From the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 through the early 1990s, the Afghan War (1978–92) caused more than six million refugees to flee to the neighboring countries of Pakistan and Iran, making Afghanistan the greatest refugee-producing country. The number of refugees fluctuated with the waves of the war, with thousands more fleeing after the Taliban takeover of 1996. The U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and continued ethnic cleansing and reprisals also caused additional displacement. Though there has been some repatriation sponsored by the U.N. from Iran and Pakistan, a 2007 UNHCR census identified over two million Afghan refugees still living in Pakistan alone.

India

The partition of the Indian subcontinent into India and Pakistan in 1947 resulted in the largest human movement in history: an exchange of eighteen million Hindus and Sikhs (from Pakistan) for Muslims (from India). During the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, owing to the West Pakistani Army's Operation Searchlight, more than ten million Bengalis fled to neighboring India.

As a result of the Bangladesh Liberation War, on March of 1971, Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, expressed full support of her Government to the Bangladeshi struggle for freedom. The Bangladesh-India border was opened to allow the panic-stricken Bengalis safe shelter in India. The governments of West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura established refugee camps along the border. Exiled Bangladeshi army officers and voluntary workers from India immediately started using these camps for recruitment and training of freedom fighters (members of Mukti Bahini).

As the violence in East Pakistan escalated, an estimated ten million refugees fled to India, causing financial hardship and instability therein. There are between one hundred and twenty six thousand and one hundred and fifty nine thousand Biharis who have been living in camp-like situations in Bangladesh ever since the war, whom Pakistan has been unwilling to accept.

Southeast Asia

Following the communist takeovers in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in 1975, about three million people attempted to escape in the subsequent decades. With massive influx of refugees daily, the resources of the receiving countries were severely strained. Large numbers of Vietnamese refugees came into existence after 1975 when South Vietnam fell to the communist forces. Many tried to escape, some by boat, thus giving rise to the phrase "boat people." The Vietnamese refugees emigrated to Hong Kong, Israel, France, the United States, Canada, Australia, and other countries, creating sizable expatriate communities, notably in the United States. The plight of the boat people became an international humanitarian crisis. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) set up refugee camps in neighboring countries to process the boat people.

The Mien or Yao lived in northern Vietnam, northern Laos, and northern Thailand. In 1975, the Pathet Lao forces began seeking reprisal for the involvement of many Mien as soldiers in the CIA-sponsored Secret War in Laos. As a token of appreciation to the Mien and Hmong people who served in the CIA secret army, the United States accepted many of the refugees as naturalized citizens (Mien American). Many more Hmong continue to seek asylum in neighboring Thailand.

Africa

Since the 1950s, many nations in Africa have suffered civil wars and ethnic strife, thus generating a massive number of refugees of many different nationalities and ethnic groups. The division of Africa into European colonies in 1885, along which lines the newly independent nations of the 1950s and 1960s drew their borders, has been cited as a major reason why Africa has been so plagued with intrastate warfare. The number of refugees in Africa increased from nearly nine hundred thousand in 1968 to close to seven million by 1992. By the end of 2004, that number had dropped to under three million refugees.

Many refugees in Africa cross into neighboring countries to find haven; often, African countries are simultaneously countries of origin for refugees and countries of asylum for other refugees. The Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, was the country of origin for nearly five hundred thousand refugees at the end of 2004, but a country of asylum for close to two hundred thousand other refugees.

Great Lakes refugee crisis

In the aftermath of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, over two million people fled into neighboring countries, in particular Zaire. The refugee camps soon came to be controlled by the former government and Hutu militants who used the camps as bases to launch attacks against the new government in Rwanda. Little action was taken to resolve the situation and the crisis did not end until Rwanda-supported rebels forced the refugees back across the border in the beginning of the First Congo War.

Europe

Beginning in 1991, political upheavals in the Balkans such as the breakup of Yugoslavia, displaced about nearly three million people by mid-1992. Seven hundred thousand of them sought asylum in Europe. In 1999 around one million Albanians escaped from Serbian persecutions.

Conflict and civil unrest in Chechenya, Caucasus due to independence proclaimed by this republic in 1991 which was not accepted by the Russian Federation, resulted in the displacement of almost two million people.

An ongoing refugee crisis began in late February 2022 after Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Nearly 8 million refugees fleeing Ukraine have been recorded across Europe, while an estimated 8 million people had been displaced within the country by late May 2022.[3] 90 percent of Ukrainian refugees were women and children, while most Ukrainian men aged 18 to 60 were banned from leaving the country.

The Americas

More than one million Salvadorans were displaced during the Salvadoran Civil War from 1975 to 1982. About half went to the United States, most settling in the Los Angeles area. There was also a large exodus of Guatemalans during the 1980s, trying to escape from the civil war and genocide there as well. These people went to southern Mexico and the U.S.

From 1991 through 1994, following the military coup d'état against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, thousands of Haitians fled violence and repression by boat. Although most were repatriated to Haiti by the U.S. government, others entered the United States as refugees. Haitians were primarily regarded as economic migrants from the grinding poverty of Haiti, the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere.

The victory of the forces led by Fidel Castro in the Cuban Revolution led to a large exodus of Cubans between 1959 and 1980. Dozens of Cubans yearly continue to risk the waters of the Straits of Florida seeking better economic and political conditions in the U.S. In 1999 the highly publicized case of six-year-old Elián González brought the covert migration to international attention. Measures by both governments have attempted to address the issue, the U.S. instituted a "Wet feet, dry feet policy" allowing refuge to those travelers who manage to complete their journey, and the Cuban government have periodically allowed for mass migration by organizing leaving posts. The most famous of these agreed migrations was the Mariel boatlift of 1980.

It is now estimated by the U.S. Committee on Refugees and Immigrants that there are around one hundred and fifty thousand Colombians in "refugee-like situations" in the United States, not recognized as refugees nor subject to any formal protection.

Issues facing refugees

An estimated 80 percent of refugees are women and children. Women often carry the heaviest burden of survival for themselves and their families. Beyond the problems faced by those who remain "warehoused" in refugee camps, others who have settled in another country still experience many challenges.

Women and adolescent girls in refugee settings are especially vulnerable to exploitation, rape, abuse, and other forms of gender-based violence. Children and youth constitute approximately fifty percent of all refugees worldwide. They are the deliberate targets of abuse, and easy prey to military recruitment and abduction. They typically miss out on years of education. More than forty million children living in conflict-affected areas have no chance to go to school.

Girls in particular face significant obstacles accessing education. Families who lack funds for school fees, uniforms, books, and so forth are often influenced by cultural norms to prioritize education for boys over girls. Girls are typically pulled out of school before boys, often to help with traditional care-giving/work roles including care for younger siblings, gathering firewood and cooking. Early or forced marriage can also derail a girl’s education.

Without an education, refugee women and youth often struggle to support themselves and their families. With refugees displaced for longer periods of time than ever before (nearly 70 percent of all refugees are now displaced for an average of 17 years), the ability for refugees—particularly women and youth—to earn a living and sustain themselves and their families (“livelihoods”) is becoming even more critical. Livelihoods are vital for the social, emotional, and economic well being of displaced persons and are a key way to increase the safety of displaced women and adolescents. Lack of education, minimal job prospects, and disproportionate responsibility at home all limit the livelihood opportunities of women and youth.

On occasion, people who have been uprooted from their homes come to the United States in search of safe haven. They may be detained by the U.S. government, often until their asylum cases are decided—which can amount to days, weeks, months, or even years. Many of those detained are women and children who seek asylum in the United States after fleeing from gender- and age-related persecution. Sometimes the children are alone, having fled abusive families or other human rights abuses. Detained women asylum seekers are also particularly vulnerable to abuse in detention. Women and children asylum seekers who reach the United States are often imprisoned and at times subjected to inhumane conditions, abuse and poor medical care, and denied legal representation and other services. Refugee advocacy organizations, including the Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, focus their programs and advocacy specifically on the needs of refugee women, children, and youth.

Apart from physical wounds or starvation, refugees may symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression. These long-term mental problems can severely impede the functionality of the person in everyday situations; it makes matters even worse for displaced persons who are confronted with a new environment and challenging situations.[7]

A study by the Department of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine demonstrated that 20 percent of Sudanese refugee minors living in the United States had a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. They were also more likely to have worse scores on all the Child Health Questionnaire subscales.[8]

Notes

- ↑ Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, Adopted on 28 July 1951 Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, United Nations. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ James Hathaway, The Rights of Refugees Under International Law (University of Michigan, 2005, ISBN 9780521834940).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 UNHCR: Ukraine, other conflicts push forcibly displaced total over 100 million for first time UNHCR, May 23, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ Framework for Durable Solutions for Refugees and Other Persons of Concern UNHCR Core Group on Durable Solutions, 2003. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Nansen International Office for Refugees History The Nobel Peace Prize 1938. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ Mark Elliott, The United States and Forced Repatriation of Soviet Citizens, 1944-47 Political Science Quarterly 88(2) (June 1973): 253-275.

- ↑ Basel El-Khodary1, Muthanna Samara1, and Chris Askew, Traumatic Events and PTSD Among Palestinian Children and Adolescents: The Effect of Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors Frontiers in Psychiatry, March 31, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ↑ P.L. Geltman, W. Grant-Knight, S.D. Mehta, C. Lloyd-Travaglini, S. Lustig, J.M. Landgraf, and P.H. Wise, The "Lost Boys of Sudan": Functional and Behavioral Health of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Re-Settled in the United States Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 159 (June 2005): 585-591. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bixler, Mark. The Lost Boys of Sudan: An American Story of the Refugee Experience. University of Georgia Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0820328836.

- Gibney, Matthew. The Ethics and Politics of Asylum: Liberal Democracy and the Response to Refugees. Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0521009379.

- Goodwin-Gill, Guy, and Jane McAdam. The Refugee in International Law. Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0199207633.

- Hathaway, James. The Rights of Refugees Under International Law. University of Michigan, 2005. ISBN 978-0521834940.

- Kemp, Charles, and Lance A. Rasbridge. Refugee and Immigrant Health: A Handbook for Health Professionals. Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521828597

- Kourula, Pirkko. Broadening the Edges: Refugee Definition and International Protection Revisited. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff, 1997.

- Marrus, Michael Robert. The Unwanted: European refugees in the 20th Century. Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0195036152.

- Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0521009676.

- Zolberg, Aristide, Astri Suhrke, and Sergio Aguayo. Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World. Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0195079166.

External links

All links retrieved January 24, 2023.

- U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants

- Refugee Council (UK)

- Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford

- UNHCR United Nations Refugee Agency.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.