Pharaoh

Pharaoh is the title given in modern parlance to the ancient Egyptian kings. In antiquity its use began during the New Kingdom (1570–1070 B.C.E.). Originally meaning "Great House," it earlier referred to the king's palace but eventually became interchangeable with the traditional Egyptian word for king, nswt. Although the rulers of Egypt were usually male, the title of pharaoh was also used on the rare occasions when a female ruled.

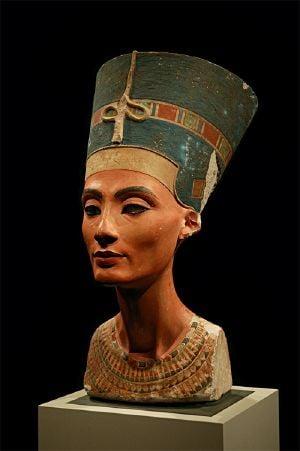

The pharaohs were often depicted wearing a striped headcloth called the nemes, an ornate kilt, and a double crown—to symbolize the unity of Upper and Lower Egypt. The crown was usually decorated by a uraeus, the upright form of an Egyptian spitting cobra.

The pharaoh was Egypt's supreme ruler, governing by royal decree through his vizier over a system of 42 districts or nomes. In spiritual affairs, the pharaohs were generally believed to be the incarnations of the god Horus during their lives and became one with Osiris in death. They were also seen as a mediator between the realm of the gods and the world of human beings.

Role

As with many ancient kings, the pharaoh was seen as the preserver of the divine order. Known in Egypt as Ma'at, this spiritual principle manifested in various environmental, agricultural, and social relationships.

The pharaoh owned and supervised the use of a large percentage of the land of Egypt. He was considered responsible for both the spiritual and economic welfare of the people. He was also the supreme authority in legal affairs and the administrator of justice, legislating by royal decree.

The pharaoh's main agent in governing the nation was the vizier, who held charge of the treasury, legal cases, taxes, and record-keeping. Under the vizier, Egypt was divided into governmental districts or nomes. Lower Egypt, from Memphis northward to the Mediterranean Sea, comprised 20 nomes. Upper Egypt was divided into 22 nomes from Elephantine, close to Egypt's border with Nubia, southward downriver along the Nile valley.

Equally important as the pharaoh's governing role was his religious function. The Egyptians saw the pharaoh as the mediator between the realm of the gods and the realm of humans. In death, the pharaoh would become one with Osiris, god of the dead, passing on his sacred powers to his son, the new pharaoh, who would then represent Osiris' son Horus.

The power of the gods was thus vested in the pharaoh. He was addressed as all-powerful and omniscient, the controller of both nature and fertility. The sacred cobras depicted on his crown were said to spit flames at the pharaoh's enemies. He was depicted in monumental statues of huge proportions, and the power of his divinity enabled him to slay thousands of enemies in battle.

Etymology

| pharaoh "pr-`3" in hieroglyphs | ||

|

The term pharaoh ("الفرعون") derives from a compound word represented as pr-`3, originally used only in larger phrases like smr pr-`3—"Courtier of the High House"—with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace itself. From the Twelfth Dynasty (twentieth century B.C.E.) onward the word appears in a wish formula or prayer—"Great House, may it live, prosper, and be in health"—but again only with reference to the royal or heavenly palace and not the person.

The earliest instance where pr-`3 is used specifically to address the king is in a letter to Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) in the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1292 B.C.E.), which is addressed to "Pharaoh, all life, prosperity, and health!."

From the Nineteenth Dynasty onwards pr-`3 on its own began to be used as regularly as the title hm.f ("His Majesty.") The first dated instance of the title being attached to a king's name occurs in Year 17 of Siamun on a fragment from the Karnak Priestly Annals. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of Pharaoh Siamun. This new practice was continued under his successor Psusennes II and the Twenty-first Dynasty kings. Meanwhile the old custom of referring to the sovereign simply as Per'o continued in traditional Egyptian narratives.

The term therefore evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to an honorific designation for the king or prince, particularly by the Twenty-Second Dynasty and Twenty-Third Dynasty (tenth through eighth centuries B.C.E.). By this time, the Late Egyptian word is reconstructed to have been pronounced *par-ʕoʔ, from which is derived the Ancient Greek φαραώ and the Late Latin pharaō. From the latter, the English language obtained the word "pharaoh."

A similar development, with a word originally denoting an attribute of the king eventually coming to refer to the king himself, can be discerned in a later period with the Arabic term sultan, originally meaning "strength" or "authority." Similarly, the name of the Canaanite god Baal-zebul may mean literally "Lord of the lofty house."

Regalia

The king of Egypt wore a double crown, created from the Red Crown of Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper Egypt. In certain situations, the pharaoh wore a blue crown of a different shape. All of these crowns typically were adorned by a uraeus—the stylized, upright form of an Egyptian spitting cobra—which was also doubled from the time of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.

The pharaoh also wore a striped headcloth called the nemes. The nemes was sometimes combined with the double crown. The pharaoh, including female pharaohs, would often wear a false beard made of goat hair during rituals and ceremonies.

Egyptologist Bob Brier (1994) has noted that despite its widespread depiction in royal portraits and inscriptions, no ancient Egyptian crown ever has been discovered. Tutankhamun's tomb, discovered largely intact, did contain such regal items as his crook and flail, but not a crown. Brier speculates that since crowns were assumed to have magical properties belonging to the office and not the person, they had to be passed on to a living successor.

Female pharaohs

Several women apparently ruled as pharaohs of Egypt. Of the three great non-consort queens of Egypt (Hatshepsut, Sobeknefru, and Twosret), Hatshepsut and possibly others took the title pharaoh in the absence of an existing word for "Queen Regnant." Also notable is Nefertiti, who may have been made co-regent (the pharaoh's equal) during the reign of Akhenaten. Some scholars further suspect that since her disappearance coincided with the accession of Pharaoh Smenkhkare to the throne after Akhenaten's death, Nefertiti was in fact Smenkhkare, making her another woman who became pharaoh in Egyptian history. Egypt's last pharaoh was Cleopatra VII, although she and several of her predecessors were Greek.

The royal lineage was traced through its women, and a pharaoh had to either descend from that lineage or marry into it. This resulted in frequent intermarriages among the royal families of Egypt, in which there was no incest taboo.

Pharaohs in the Bible

The biblical use of the term pharaoh reflects Egyptian usage with fair accuracy. However, in the Book of Genesis, several references to the king of Egypt as "Pharaoh" are anachronistic, since the title was not in use yet in the supposed time of the patriarchs. The saga of Joseph's becoming the governor of Egypt under the king of that time (Gen. 40-46) nevertheless accurately reflects the Egyptian system of a vizier acting on the king's behalf, although the story itself cannot be historically confirmed. The episodes of Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh, especially the scene of Moses' serpent-staff swallowing Pharaoh's serpent-staff (Ex. 7), are reflective of a battle between the Egyptian king's supposed divine power vis à vis the power of the Hebrew deity.

The first king of Egypt mentioned by name in the Bible is Shishaq (probably Sheshonk I), the founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty and contemporary of Rehoboam and Jeroboam (1 Kings 11:40; 2 Chronicles 12:2 sqq.). 2 Kings 17:4 says that Hoshea sent letters to "So, King of Egypt," whose identification is still not certain. He has been identified with Osorkon IV, who was a minor king at Tanis who ruled over a divided Egypt, with Tefnakht of Sais, and with Pi'ankhy.

Pharaoh Taharqa, who was the opponent of Sennacherib, is called "Tirhakah King of Ethiopia" in the Bible (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9), and hence is not given the title pharaoh, which he bears in Egyptian documents. Last mentioned are two kings of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty: Necho II, who slew King Josiah at Megiddo (2 Kings 23:29 sqq.; 2 Chronicles 35:20 sqq.), and Apries, called Hophra in Jeremiah 44:30. Both are indeed styled pharaoh in Egyptian records.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brier, Bob. Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art. New York: W. Morrow, 1994. ISBN 9780688102722

- Casson, Lionel. The Pharaohs. [Chicago, IL]: Stonehenge, 1981. ISBN 9780867060416

- Gardiner, Alan Henderson. Egypt of the Pharaohs: An Introduction. London: Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 9780195002676

- Harris, Geraldine. Gods & Pharaohs from Egyptian Mythology. (World mythologies series.) New York: Schocken Books, 1983. ISBN 9780805238020

- James, T. G. H. Pharaoh's People: Scenes from Life in Imperial Egypt. London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2007. ISBN 9781845113353

External links

All links retrieved November 23, 2022.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.