Nefertiti

Nefertiti (pronounced *nafratiːta; c. 1370 B.C.E. - c. 1330 B.C.E.) was the chief consort of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten (formerly Amenhotep IV; (reigned c. 1353–36 B.C.E.). Her name roughly translates to "the beautiful (or perfect) one has arrived." She was also known as "Ruler of the Nile" and "Daughter of gods."

In Akhenaten's new state religion centered on the sun god, he and Nefertiti were depicted as the primeval first couple. Nefertiti was also known throughout Egypt for her beauty. She was said to be proud of her long, swan-like neck and invented her own makeup using the Galena plant. She also shares her name with a type of elongated gold bead, called nefer, that she was often portrayed as wearing.

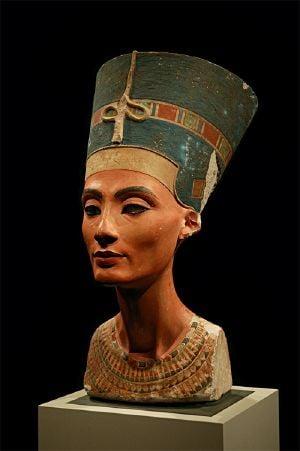

Long forgotten to history, Nefertiti was made famous when her bust was discovered in the ruins of an artist's shop in Amarna in 1912, now in Berlin's Altes Museum, shown to the right. The bust is one of the most copied works of ancient Egypt.

Nefertiti is depicted in images and statuary in a large image denoting her importance. Many images of her show simple family gatherings with her husband and daughters. She is also known as the mother-in-law and stepmother of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun.

Much controversy lingers about Nefertiti after the twelfth regal year of Akhenaten, when her name vanishes. Nefertiti may have also ruled as pharaoh in her own right under the name Neferneferuaten, or Smenkhkare.

Family

| Nefertiti in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||||

|

Nefertiti's parentage is not known with certainty, but it is generally believed that she was the daughter of Ay, later to be pharaoh after Tutankhamen. She had a younger sister, Moutnemendjet. Another theory identifies Nefertiti with the Mitanni princess Tadukhipa.

Nefertiti was married to Amenhotep IV around 1357 B.C.E. and was later promoted to be his queen. Images exist depicting Nefertiti and the king riding together in a chariot, kissing in public, and Nefertiti sitting on the king's knee, leading scholars to conclude that the relationship was a loving one. The couple had six known daughters, two of whom became queens of Egypt:

- Meritaten: b. 1356 B.C.E., believed to have served as her father's queen

- Meketaten: b. 1349 B.C.E., died at 13 or 14

- Ankhesenpaaten: b. 1346 B.C.E., also known as Ankhesenamen, later queen to Tutankhamun,

- Neferneferuaten Tasherit: b. 1344 B.C.E.

- Neferneferure: b. 1341 B.C.E.

- Setepenre: b. 1339 B.C.E.

Femininity was important to Akhenaten/Amenhotep in both his personal life and his faith. No other founder of a religion in the ancient world is known for whom women played a comparable role. Akhenaten had a number of different women depicted in nearly every image of a cult ritual or state ceremony he conducted as king at his capital at Amarna honoring the sun god, where Nefertiti especially is featured very prominently.

Many images depict the whole royal family in domestic scenes. Nefertiti is shown as a beloved wife and mother. King Akhenaton's legendary love is seen in the hieroglyphs at Amarna, and he even wrote a love poem to Nefertiti:

"…And the Heiress, Great in the Palace, Fair of Face,

Adorned with the Double Plumes, Mistress of Happiness, Endowed with Favors, at hearing whose voice the King rejoices, the Chief Wife of the King, his beloved, the Lady of the Two Lands,

Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti, May she live for Ever and Always…" [1]

New religion

In year 4 of Amenhotep IV's reign (1346 B.C.E.) the sun god Aten became the dominant national god. The king led a religious revolution closing the older temples and promoting Aten's central role. Nefertiti had played a prominent role in the old religion, and this continued in the new system. She worshiped alongside her husband and held the unusual kingly position of priest of Aten. In the new, virtually monotheistic religion, the king and queen were viewed as "a primeval first pair," through whom Aten provided his blessings. They thus formed a royal triad or trinity with Aten, through which Aten's "light" was dispensed to the entire population.

This year is believed to mark the beginning of the king's construction of a new capital, Akhetaten, ("The Horizon of the Aten") at what is known today as Amarna. In his Year 5, Amenhotep IV officially changed his name to Akhenaten. In Year 7 (1343 B.C.E.) the capital was moved from Thebes to Amarna, though construction of the city seems to have continued for two more years (until 1341 B.C.E.). The new city was dedicated to the royal couple's new religion, and Nefertiti's famous bust is also thought to have been created around this time. The bust itself is notable for exemplifying the unique understanding Ancient Egyptians had regarding realistic facial proportions.

In images, Nefertiti, is depicted as a fertility symbol, with images of the couple's six daughters shown frequently. She exhibits the same clothing fashion as in images of Tefnut, the wife of the god Amun. She wears the same tight, "clinging robe tied with a red sash with the ends hanging in front. She also wears the short rounded hairstyle… exemplified by a Nubian wig, the coiffure of her earlier years, alternating with a queen's tripartite wig, both secured by a diadem, replaced by a crown with double plumes and a disk, like Tiye and her later Kushite counterparts." Some images show her dressed in a mortar-shaped cap that was the headgear of Tefnut, in her leonine aspect of a sphinx after the fourth regal year. Nefertiti was then referred to as "Tefnut herself," at once the daughter and the wife of the sun-god. Therefore, Nefertiti played an equal role with the king who was the image of Re/Ra.[2]

In an inscription estimated to November 21 of Year 12 (approx. 1338 B.C.E.), her daughter Meketaten is mentioned for the last time; she is thought to have died shortly after that date. Several fragments were found at Akhetaten indicating she had died and are now located in the Louvre and Brooklyn Museums[3]. A relief in Akhenaten's tomb in the Royal Wadi at Amarna appears to show her funeral.

During Akhenaten's reign (and perhaps after) Nefertiti enjoyed unprecedented power, and by the twelfth year of his reign, there is evidence that she may have been elevated to the status of co-regent, equal in status to the pharaoh himself. She is often depicted on temple walls in the same size as him, signifying her importance, and is shown alone worshiping the god Aten[4]. Perhaps most impressively, Nefertiti is shown on a relief from the temple at Amarna smiting a foreign enemy with a mace before Aten. Such depictions had traditionally been reserved for the pharaoh alone, and yet Nefertiti was depicted as such.

Akhenaten had the figure of Nefertiti carved onto the four corners of his granite sarcophagus, and it was she who is depicted as providing the protection to his mummy, a role traditionally played by the traditional female deities of Egypt: Isis, Nephthys, Selket and Neith.

Nefertiti's rule and/or disappearance

In the regal year 12, Nefertiti's name ceases to be found. Some think she either died from a plague that swept through the area or fell out of favor, but recent theories have denied this claim.

Shortly after her disappearance from the historical record, Akhenaten took on a co-regent with whom he shared the throne of Egypt. This has caused considerable speculation as to the identity of that person. One theory states that it was Nefertiti herself in a new guise as a female king, following the historical role of other women leaders such as Sobkneferu and Hatshepsut. Another theory introduces the idea of there being two co-regents, a male son, Smenkhkare, and Nefertiti under the name Neferneferuaten (translated as "The Aten is radiant of radiance [because] the beautiful one is come" or "Perfect One of the Aten's Perfection").

The Coregency Stela may show her as a co-regent with her husband, causing some schools of thought to believe that Nefertiti ruled briefly after her husband's death and before the accession of Tutankhamun, although this identification is called into doubt by recent research.[5]

Some scholars are adamant about Nefertiti assuming the role of co-regent during or after the death of Akhenaten. Jacobus Van Dijk, responsible for the Amarna section of the Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, believes that Nefertiti indeed became co-regent with her husband, and that her role as queen consort was taken over by her eldest daughter, Meryetaten (Meritaten) with whom Akhenaten had several children. (The taboo against incest did not exist for the royal families of Egypt.) Also, it is Nefertiti's four images that adorn Akhenaten's sarcophagus, not the usual goddesses, which indicates her continued importance to the pharaoh up to his death and refutes the idea that she fell out of favor. It also shows her continued role as a deity, or semi-deity, with Akhenaten.

On the other hand, Cyril Aldred, author of Akhenaten: King of Egypt, states that a funerary shawabti found in Akhenaten's tomb indicates that Nefertiti was simply a queen regnant, not a co-regent and that she died in the regal year 14 of Akhenaten's reign, her daughter dying the year before.

Some theories hold that Nefertiti was still alive and held influence on the younger royals who married in their teens. Nefertiti would have prepared for her death and for the succession of her daughter, Ankhesenpaaten, now named Ankhsenamun, and her stepson and now son-in-law, Tutankhamun. This theory has Neferneferuaten dying after two years of kingship and being then succeeded by Tutankhamun, thought to have been a son of Akhenaten. The new royal couple was young and inexperienced, by any estimation of their age. In this theory, Nefertiti's own life would have ended by Year 3 of Tutankhaten's reign (1331 B.C.E.). In that year, Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun and abandoned Amarna to return the capital to Thebes, as evidence of his return to the official worship of Amun.

As the records are incomplete, it may be that future findings of both archaeologists and historians will develop new theories vis-à-vis Nefertiti and her precipitous exit from the public stage.

Missing mummy

There is no concrete information available regarding Nefertiti's death or burial, and the location of Nefertiti's body has long been a subject of curiosity and speculation.

On June 9, 2003, archaeologist Joann Fletcher, a specialist in ancient hair from the University of York in England, announced that Nefertiti's mummy may have been one of the anonymous mummies stored in tomb Ahmenhotep II, KV35 known as "the Younger Lady." Fletcher also indicates other clues of a doubled-pierced ear lobe, which she claims was a "rare fashion statement in Ancient Egypt"; a shaven head; and the clear impression of the tight-fitting brow-band worn by royalty. "Think of the tight-fitting, tall blue crown worn by Nefertiti, something that would have required a shaven head to fit properly," said Fletcher.[6] Egyptologist Marianne Luban had already made the same speculation as early as 1999 in an article entitled "Do We Have the Mummy of Nefertiti?"[7] Furthermore, Fletcher suggested that Nefertiti was in fact the Pharaoh Smenkhkare. Some Egyptologists hold to this view though the majority believe Smenkhkare to have been a separate person.

Fletcher's team claimed that the mummy they examined was damaged in a way suggesting the body had been deliberately desecrated in antiquity. Mummification techniques, such as the use of embalming fluid and the presence of an intact brain, suggested an eighteenth dynasty royal mummy. Other features support the identification were the age of the body, the presence of embedded nefer beads, and a wig of a rare style worn by Nefertiti. They further claimed that the mummy's arm was originally bent in the position reserved for pharaohs holding a royal scepter, but was later snapped off and replaced with arm in a normal position.

However, most Egyptologists, among them Kent Weeks and Peter Locavara, generally dismiss Fletcher's claims as unsubstantiated. With the absence of DNA evidence, any circumstantial evidence, such as hairstyle and arm position, is not reliable enough to pinpoint a single, specific historical person. The eighteenth dynasty was one of the largest and most prosperous dynasties of ancient Egypt, and a female royal mummy could be any of a hundred royal wives or daughters from the dynasty's more than 200 years on the throne.

Recent research on "The Younger Lady" was conducted by Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass, head of Egypt's Supreme Council for Antiquities. The mummy was put through CT scan analysis and researchers concluded that she may be Tutankhamun's biological mother, Kiya, rather Nefertiti. In addition, there is controversy about both the age and gender of the mummy.

An article in A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt by Susan E. James suggests that the "Elder Lady" mummy (found in the same tomb) may be Nefertiti's body.[8] However, other evidence suggest that it is actually another queen, Tiye.

To date, the mummy of Nefertiti, the famous and iconic Egyptian queen, has not been conclusively found.

Legacy

Nefertiti's place as an icon in popular culture is secure as she has become somewhat of a celebrity due to the rare find of her bust. After Cleopatra, she is the second most famous queen of Egypt in the Western imagination and her image has influenced, through photographs, and changed standards of feminine beauty of the twentieth century, and is often referred to as "the most beautiful woman in the world."

Her most important legacy, though, may be that she and Pharaoh Akhenaten tried to establish a monotheistic religion in Egypt, which, if it had survived, would have created a very different history for the Middle East, with important ramifications for the current religious/political turmoil of the area.

Notes

- ↑ Nefertiti crystalinks.com Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Jimmy Dunn, Queen Nefertiti of Egypt (1999) touregypt.net Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. (Thames & Hudson, 2004), 156

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves. Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet. (Thames & Hudson, 2005), 172

- ↑ James Allen, The Amarna Succession history.memphis.edu retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Jimmy Dunn, Queen Nefertiti of Egypt, (1999) touregypt.net Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Marianne Laban, Do We Have the Mummy of Nefertiti? geocities.com All links retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ↑ Susan E. James, KMT article "Who is Elder Lady" egyptology.com Retrieved November 5, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aldred, Cyril. Akhenaten: King of Egypt. Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1988. ISBN 0500276218.

- Aldred, Cyril. Akhenaten and Nefertiti. The Viking Press, 1973. ASIN B000I6LVC2

- Allen, James. Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780521774833.

- Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs (The Reign-By-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt). Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1994. ISBN 0500050740.

- Dodson, Aidan and Dyan Hilton. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2004. ISBN 978-0500051283.

- Freed, Rita E., Sue D’Auria, and Yvonne J. Markowitz, (eds.), Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen. (1999)

- Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell, 1994. ISBN 978-0631193968.

- Reeves, Nicholas. Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet. Thames & Hudson, 2005. ISBN 0500285527.

- Reeves, Nicholas and Richard H. Wilkinson. The Complete Valley of the Kings. Thames & Hudson, 2008. ISBN 978-0500284032.

- Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, USA, 2004. ISBN 978-0192804587.

- Smith, G. Elliot. The Royal Mummies. Duckworth Publishers, (orig. 1912) 2000. ISBN 978-0715629598.

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Nefertiti: Egypt’s Sun Queen. Viking Adult, 1999. ISBN 978-0670869985.

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2006. ISBN 978-0500051450.

External Links

All links retrieved November 11, 2022.

- Queen Nefertiti Crystal Links

- Nefertiti, Perhaps Egypt's Most Beautiful Queen Tour Egypt

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.