Archives refer to a collection of records, and also refers to the location in which these records are kept.[1] Archives are made up of records which have been created during the course of an individual or organization's life. In general an archive consists of records which have been selected for permanent or long-term preservation. Records, which may be in any media, are normally unpublished, unlike books and other publications. Archives may also be generated by large organizations such as corporations and governments. Archives are distinct from libraries insofar as archives hold records which are unique. Archives can be described as holding information "by-products" of activities, while libraries hold specifically authored information "products".[2] The word 'archives' is the correct terminology, whereas 'archive' as a noun or a verb is related to computer science. [3]

A person who works in archives is called an archivist. The study and practice of organizing, preserving, and providing access to information and materials in archives is called archival science.

Etymology

The word archives (pronounced /'ɑː(ɹ}.kaɪvs/) is derived from the Greek arkhé meaning government or order (compare an-archy, mon-archy). The word originally developed from the Greek "arkheion" which refers to the home or dwelling of the Archon, in which important official state documents were filed and interpreted under the authority of the Archon.

Archive Users and Institutions

Historians, genealogists, lawyers, demographers, and others conduct research at archives. [4] The research process at each archive is unique, and depends upon the institution in which the archive is housed. While there are many different kinds of archives, the most recent census of archivists in the United States identified five major types: academic, for profit (business), government, non profit, and other. [5]

Academic archives

Archives existing in colleges, universities, or other educational facilities are usually grouped as academic archives. Academic archives typically exist within a library, and duties may be carried out by an archivist or a librarian. Occasionally, history professors may run a smaller academic archive.[6] Academic archives exist to celebrate and preserve the history of their school and academic community.[7] The inventory of an academic archive may contain items such as papers of former professors and presidents, memorabilia related to school organizations and activities, and items the academic library wishes to remain in a closed-stack setting, such as rare books or thesis copies. It is always a good idea to contact an academic archive before visiting, as the majority of these institutions are available by appointment only. Users of academic archives are often graduate students and those wishing to view rare or historical documents for research purposes. Many academic archives work closely with alumni relations to help raise funds for their library or school.[8] Because of their library setting, a degree from certified by the American Library Association is preferred for employment in an academic archive.

Business (for profit) archives

Archives located in for-profit institutions are usually those owned by a private business. Examples of prominent business archives in the United States include Coca-Cola (which also owns the separate museum World of Coke), Proctor and Gamble, and Levi Strauss & Co.. These corporate archives maintain historic documents and items related to the history of their companies.[9] Business archives serve the purpose of helping their corporations maintain control over their brand by retaining memories of the company's past. Especially in business archives, records management is separate from the historic aspect of archives. Workers in these types of archives may have any combination of training and degrees, from either a history or library background. These archives are typically not open to the public and only used by workers of the owner company, although some will allow approved visitors by appointment.[10] Business archives are concerned with maintaining the integrity of their parent company, and therefore selective of how their materials may be used.[11]

Government archives

The category of government archives includes those institutions run on a local and state level as well as those run by the national (federal) government. Anyone may use a government archive, and frequent users include reporters, genealogists, writers, historians, students, and anyone wanting more information on the history of their home or region. While it is a good idea to make an appointment before visiting government archives, at many government archives no appointment is required, as they are open to the public.[12]

In the United States, NARA archives exist not only in the District of Columbia, but regionally as well.[13] Some city or local governments may have repositories, but their organization and accessibility varies widely.[14] State or Province archives typically require at least a bachelor's degree in history for employment, although some ask for certification by test (government or association) as well.

In France, the Directorate of the Archives of France (Direction des Archives de France) in the Ministry of Culture manages the National Archives (Archives nationales) which possess 364 km. (226 miles) of archives as of 2004 (the total length of occupied shelves put next to each other), with original records going as far back as C.E. 625, as well as the departmental archives (archives départementales), located in the préfectures of each of the 100 départements of France, which possess 1,901 km. (1,181 miles) of archives (as of 2004), and also the local city archives, about 600 in total, which possess 449 km. (279 miles) of archives (as of 2004).[15] Put together, the total volume of archives under the supervision of the Directorate of the Archives of France is the largest in the world, a testimony to the very ancient nature of the French state which has been in existence for more than eleven centuries already.

Non-Profit Archives

Non-profit archives include those in historical societies, not for profit businesses such as hospitals, and the repositiories within foundations. Non-profit archives are typically set up with private funds from donors to preserve the papers and history of specific persons or places. Often these institutions rely on grant funding from the government as well.[16] Depending on the funds available non-profit archives may be as small as the historical society in a rural town to as big as a state historical society that rivals a governmental archives. Users of this type of archive may vary as much as the institutions that hold them. Employees of non-profit archives may be professional archivists or volunteers, and the education required varies with the demands of the collection's user base.[17]

Special (other) archives

Some archives defy categorization. There are tribal archives within the Native American nations in North America, and there are archives that exist within the papers of private individuals. Many museums keep archives in order to prove the provenance of their pieces. Any institution or persons wishing to keep their significant papers in an organized fashion that employs the most basic principles of archival science may have an archive. In the 2004 census of archivists taken in the United States, 2.7 percent of archivists were employed in institutions that defied categorization. This was a separate figure from the 1.3 percent that identified themselves as self-employed.[18]

Archives in history

The word "archives" can refer to any organized body of records fixed on media. The management of archives is essential for effective day-to-day organizational decision making, and even for the survival of organizations. Archives were well developed by the ancient Chinese, the ancient Greeks, and ancient Romans. Modern archival thinking has many roots in the French Revolution. The French National Archives, who possess perhaps the largest archival collection in the world, with records going as far back as C.E. 625, where created in 1790 during the French Revolution from various government, religious, and private archives seized by the revolutionaries.

Archival Science

Archival science is the theory and study of the safe storage, cataloguing and retrieval of documents and items. [19] Emerging from diplomatics,[20] the discipline also is concerned with the circumstances (context) under which the information or item was, and is used. Archival Science also encompasses the study of past efforts to preserve documents and items, remediation of those techniques in cases where those efforts have failed, and the development of new processes that avoid the pitfalls of previous (and failed) techniques. The field also includes the study of traditional and electronic catalogue storage methods, digital preservation and the long range impact of all types of storage programs. [21]

Traditionally, archival science has involved time honored methods for preserving items and information in climate controlled storage facilities. This technique involved both the cataloguing and accession of items into a collection archive, their retrieval and safe handling. However, the advent of digital documents and items, along with the development of electronic databases has caused the field to revaluate the means by which it not only accounts for items, but also how it maintains and accesses both information on items and the items themselves.[22]

While generally associated with museums and libraries, the field also can pertain to individuals who maintain private collections (item or topic specific) or to the average person who seeks to properly care for, and either stop or slow down the deterioration of their family heirlooms and keepsakes.

Archival Science and course work pertaining to archival techniques as a course of study is taught in colleges and universities, usually under the umbrella of Information science or paired with a History program.

Professional organizations, such as the Society of American Archivists (SAA), also exist to act to further the study and professional development of the field. In 2002 SAA published Guidelines for a Graduate Program in Archival Studies.[23] but these guidelines have not been adopted by the majority of programs providing degrees for those entering the archives field. As a result, practitioners of archival science may come from a varied background of library, history, or museum studies programs, and there is little uniformity in the education of new archivists entering the job market.

Archivist

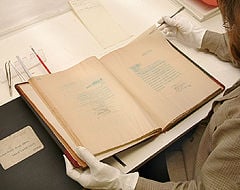

An archivist is a professional who assesses, collects, organizes, preserves, maintains control over, and provides access to information determined to have long-term value. The information maintained by an archivist can be any form of media (photographs, video or sound recordings, letters, documents, electronic records, etc.). As Richard Pearce-Moses wrote, "Archivists keep records that have enduring value as reliable memories of the past, and they help people find and understand the information they need in those records." [24]

Determining what records have enduring value is not always easy. Archivists must also select records valuable enough to justify the costs of storage and preservation, plus the labor intensive expenses of arrangement, description, and reference service. [25] The theory and scholarly work underpinning archives practices is called archival science.

Duties and work environment

Archivists' duties include acquiring and appraising new collections, arranging and describing records, providing reference service, and preserving materials. In arranging records, archivists apply two important principles: provenance and original order, sometimes referred to as respect des fonds. Provenance refers to the origin of records, essentially who created them. The idea of respect des fonds is applied by keeping records in their original order as established and maintained by the creator(s). This also means that records from one corporate body should not be mixed with records from another. Original order is not always the best way to maintain some collections though, and archivists must use their own experience and current best practices to determine the correct way to keep collections of mixed media or those lacking a clear original arrangement. [26]

American archivists are also guided in their work by a code of ethics. [27] Alongside their work behind the scenes arranging and caring for collections, archivists assist users in interpreting collections and answering inquiries. This reference work can be just part of an archivist's job in a smaller organization, or consist of most of their occupation in a larger archive where specific roles (such as processing archivist and reference archivist) may be delineated. [28]

Archivists work for a variety of organizations, including government agencies, local authorities, museums, hospitals, historical societies, businesses, charities, corporations, colleges and universities, and any institution whose records may potentially be valuable to researchers, exhibitors, genealogists, or others. Alternatively, they could also work on the collections of a large family or even of an individual. Applicants for archives jobs usually outnumber positions available.[29]

Archivists are often educators as well; it is not unusual for an archivist employed at a university or college to lecture in a subject related to their collection. Archivists employed at cultural institutions or for local government frequently design educational or outreach programs to further the ability of archive users to understand and access information in their collections. This might include such varied activities as exhibitions, promotional events or even media coverage.[30]

The advent of Encoded Archival Description, along with increasing demand for materials to be made available online, has required archivists to become more tech-savvy in the past decade. Many archivists are now acquiring basic XML skills in order to make their finding aids available to researchers online.[31]

Skills

Because of the varied nature of the job and organisations and work environment, archivists need to have a wide range of skills:

- Those who work in reference and access-oriented positions need to be good with people, so that they are able to help them with their research.

- An ability to apply some basic knowledge of conservation is needed to help extend the useful life of cultural artifacts. Many different types of media (such as photographs, acidic papers, and unstable copy processes) can deteriorate if not stored and maintained properly. [32]

- Although many archival collections are comprised of paper records, increasingly archivists must confront the new challenges posed by the preservation of electronic records, so they need to be forward-looking and technologically proficient.[33]

- Because of the amount of sorting and listing, they need to be very logical and organised and be able to pay attention to detail.

- When cataloging records, or when assisting users, archivists need to have some research skills.

Educational preparation

The educational preparation for archivists varies from country to country.

Republic of Ireland

In Ireland, the University College Dublin School of History and Archives offers a Higher Diploma in Archival Studies, recognised by the Society of Archivists.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, there are currently five full- or part-time professional Masters courses in archives administration or management which are recognised by the Society of Archivists. Students are expected to have relevant paid or voluntary work experience before obtaining a place on the UK courses; many undertake a year's traineeship. Also, in Great Britain, certification can be pursued via the Registration Scheme offered by the Society of Archivists.

United States

According to the most recent professional census of American Archivists published, most of those in the United States have earned a Masters degree.[34] However, the exact type of degree can vary; the most common sorts of advanced degrees held by archivists are in archival science, history, library science, or library and information science. It is also possible for archivists to earn a doctorate in library, or library and information, science. Archivists with a Ph. D. often work as teaching faculty or deans and directors of archival programs.[35] In 2002, the Society of American Archivists published Guidelines for a Graduate Program in Archival Studies.[36]

Also in the United States, the Academy of Certified Archivists offers supplemental archival training by means of a certification program. Critics of ACA certification object to its yearly membership fees, the theoretical versus practical nature of its tests, and the need for members to re-certify every five years. Many positions in government archives require certification from the ACA, but due to its controversial nature, the ACA is not required by all employers in the United States.

Professional Organizations and Continuing Education

Many archivists belong to a professional organization, such as the Society of American Archivists, the Association of Canadian Archivists, the Society of Archivists (UK/Ireland) and the Australian Society of Archivists, as well as any number of local or regional associations. These organizations often provide ongoing educational opportunities to their members and other interested practitioners. In addition to formal degrees and or apprenticeships, many archivists take part in continuing education opportunities as available through professional associations and library school programs. New discoveries in the fields of media preservation and emerging technologies require continuing education as part of an archivist's job in order to stay current in the profession.[37]

History of the profession

In 1898 three Dutch archivists, Samuel Muller, Johan Feith, and Robert Fruin, published the first Western text on archival theory entitled "Manual for the Arrangement and Description of Archives." Produced for the Dutch Association of Archivists, it set out one hundred rules for archivists to base their work around. Notably within these rules the principle of preserving provenance and original order was first argued for as an essential trait of archival arrangement and description.[38]

The next major text was written in 1922 by Sir Hilary Jenkinson, the then Deputy Keeper of the British Public Records Office, entitled "Manual of Archive Administration." In this work Jenkinson states that archives are evidence and that the moral and physical defence of this evidential value is the central tenet of archival work. He further outlines his ideas of what an Archive should be and how it should operate.

In 1956, T. R. Schellenberg published "Modern Archives." Schellenberg's work was intended to be an academic textbook defining archival methodology and giving archivists specific technical instruction on workflow and arrangement. Moving away from Jenkinson's organic and passive approach to archival acquisition, where the administrator decided what was kept and what was destroyed, Schellenberg argued for a more active approach by archivists to appraisal. His primary (administrative) and secondary (research) value model for the management and appraisal of records and archives allowed government archivists greater control over the influx of material that they faced after the Second World War. As a result of the widespread adoption of Schellenberg's methods, especially in the United States of America, modern Records Management as a separate but related discipline was born.[39]

In 1972, Ernst Posner published Archives in the Ancient World. Posner's work emphasized that archives were not new inventions, but had existed in many different societies throughout recorded history.

In 1975, essays by Margaret Cross Norton were collected under the title of "Norton on Archives: The Writings of Margaret Cross Norton on Archival and Records Management." Norton was one of the founders of the Society of American Archivists, and wrote essays based on her decades of experience working in the Illinois State Archives.

Notes

- ↑ [1] Glossary of Library and Internet Terms. accessdate 2007-04-30 University of South Dakota Library

- ↑ [2] A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology accessdate 2007-04-06 www.archivists.org

- ↑ [3] definition of archive. accessdate 2007-04-30

- ↑ [4] What Are Archives? accessdate 2007-04-30 National Museum of American History

- ↑ Victoria Irons Walch, 2006. Archival Census and Education Needs Survey in the United States: Part 1: Introduction. The American Archivist 69 (2):294-309 [5] Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ William J. Maher. 1992. The Management of College and University Archives. (Metuchen, New Jersey: Society of American Archivists & The Scarecrow Press, Inc.)

- ↑ [6] Welcome to University Archives and Records Management. accessdate 2007-05-08 Kennesaw State University Archives.

- ↑ Guidelines for College and University Archives. Society of American Archivists.

- ↑ [7]Business Archives Council. accessdate 2007-05-08 Business Archives Council.

- ↑ [8] Directory of Corporate Archives. accessdate 2007-05-08 Hunter Information Management.

- ↑ Business Archives in North America - Invest in your future: Understand your past. Society of American Archivists.

- ↑ [9] Directions for Change. accessdate 2007-05-09 Libraries and Archives Canada.

- ↑ [10] The National Archives. accessdate 2007-05-09 United States National Archives and Records Administration.

- ↑ [11] U.S. - State Level Records Repositories: State Libraries, Archives, Genealogical & Historical Societies] accessdate 2007-05-09 Cyndi's List of Genealogy Sites on the Internet.

- ↑ (French)[12] Les archives en France. accessdate 2007-05-15 Quid - 2007.

- ↑ Dorothy Weyer. 1995. A Primer for Local Historical Societies: Revised and Expanded from the First Edition. (AltaMira Press), 122 [13]. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Walter Muir Whitehill. 1962. Independent Historical Societies: An Enquiry into Their Research and Publication Functions and Their Financial Future. (Boston, Masssachusetts: The Boston Athenaeum), Introduction, 311

- ↑ Victoria Irons Walch, 2006. Census: A Closer Look. The American Archivist 69 (2): 327-348 [14] accessdate 2007-05-08. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ [15] A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology. accessdate 2007-04-03 Society of American Archivists.

- ↑ Luciana Duranti and Heather MacNeil. The Protection of the Integrity of Electronic Records: An Overview of the UBC-MAS Research Project, Archivaria 1 (42) (Jan. 1996): 46-47. Accessed 2007-02-16.

- ↑ [16] The Archival Paradigm—The Genesis and Rationales of Archival Principles and Practices. accessdate 2007-04-03 Council on Library and Information Resources.

- ↑ [17] Forward to Standards for Archival Description: A Handbook] accessdate 2007-04-03

- ↑ [18] Guidelines for a Graduate Program in Archival Studies. accessdate 2007-04-03

- ↑ Richard Pearce-Moses, "Identity and Diversity: What Is an Archivist?" Archival Outlook (March/April 2006).

- ↑ Gregory Hunter. 2003. Developing and Maintaining Practical Archives. (New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc.) [19]. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ James M. O'Toole and Richard J. Cox. 2006. Understanding Archives and Manuscripts. (Chicago: Society of American Archivists).

- ↑ {{SAA Code of Ethics. [20] Society of American Archivists.

- ↑ F. O'Donnell, 2000. Reference Service in an Academic Archives. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 26 (2): 110-118 [21] accessdate 2007-04-20. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Curators, and Museum Technicians accessdate 2007-04-20 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- ↑ for College and University Archives, Section IV. Core Archival Functions, Subsection D. Service Society of American Archivists.

- ↑ [22] Encoded Archival Description. accessdate 2007-04-23 Archives Hub.

- ↑ Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler. 1993. Preserving Archives and Manuscripts. (Chicago: Society of American Archivists)

- ↑ [23] The Archival Paradigm—The Genesis and Rationales of Archival Principles and Practices. accessdate 2007-04-03 Council on Library and Information Resources.

- ↑ [24] Archival Census and Education Needs: Survey in the United States. accessdate 2007-04-04 Society of American Archivists.

- ↑ Elizabeth Yakel and Jeannette Bastian, 2007. (Fall/Winter) Census: Report on Archival Graduate Education. American Archivist 69 (2): 349-366[25] accessdate 2007-04-04. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ ][26] Guidelines for a Graduate Program in Archival Studies. accessdate 2007-03-30 Society of American Archivists.

- ↑ Nancy Zimmelman, 2007. (Fall/Winter) Census: Report on Continuing Education. American Archivist 69 (2): 367-395 [27] accessdate 2007-04-04. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Terry Cook. 1997. What is Past is Prologue: A History of Archival Ideas Since 1898, and the Future Paradigm Shift. (Canada: Archivaria Vol. 43. Association of Canadian Archivists [28]. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Theodore R. Schellenberg. 1956. Modern Archives: Principles and Techniques. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brosius, Maria. Ancient Archives and Archival Traditions: Concepts of Record-Keeping in the Ancient World. Oxford studies in ancient documents. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0199252459

- O'Toole, James M., and Richard J. Cox. Understanding Archives & Manuscripts. Archival fundamentals series. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists, 2006. ISBN 1931666202

- Schellenberg, T. R. The Management of Archives. Columbia University studies in library service, no. 14. New York: Columbia University Press, 1965. ISBN 0231028121

- Stein, R. Conrad. The National Archives. Watts library. Danbury, Conn: F. Watts, 2002. ISBN 0531120325

- Szucs, Loretto Dennis, and Sandra Hargreaves Luebking. The Archives: A Guide to the National Archives Field Branches. Salt Lake City, UT: Ancestry Pub, 1988. ISBN 091648923X

External links

All links retrieved August 12, 2023.

- Archives Hub—gateway to descriptions of archives held in UK universities and colleges, part of the National Archives Network.

- InterPares Project—international project on electronic records.

- Access to Archives (A2A)—the English strand of the UK archives network.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.