Althea Gibson

Althea Gibson (August 25, 1927 – September 28, 2003) was an American sportswoman who, on August 22, 1950, became the first African-American woman to be a competitor on the world tennis tour. Supremely athletic, Gibson honed her talent to capture eleven Grand Slam championships during her career.

Faced with difficult obstacles from early in her life, she was able to rise above racial adversity, and is sometimes referred to as "the Jackie Robinson of tennis" for breaking the "color barrier." Graceful in victory and in defeat, she won many accolades during her life, and was named the Woman Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press both in 1957 and 1958, and was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1971.

Though she shied away from the title of trailblazer, she is often cited as a pioneer for the African- American athletes that followed, including Arthur Ashe, Venus Williams, and Serena Williams.

Early life

Gibson was born to poor sharecropping parents in Silver, South Carolina and was raised in Harlem, New York City. She and her family were on welfare. Gibson had difficulty in school and was often truant. She ran away from home quite frequently. Despite her troubles as a youth, she showed promise as an athlete. She excelled in horsemanship and also competed in golf, basketball, and paddle tennis. Her talent and affinity for paddle tennis led her to win tournaments sponsored by the Police Athletic League and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. She was first introduced to tennis at the Harlem River Tennis Courts by musician Buddy Walker, who noticed her playing table tennis. Dr. Walter Johnson, a Lynchburg, Virginia physician and Dr. Hubert Eaton of Wilmington, North Carolina, who were both avid tennis players, helped with her training.

Tennis career

Gibson received sponsorship and moved to Wilmington, North Carolina in 1946 to continue her tennis training. The following year, at the age of 20, she won the first of ten consecutive national championships run by the American Tennis Association, the then-governing body for black tournaments. Limited to these tournaments due to racial segregation, Gibson was not able to transcend the color barrier until age 23, when fellow player Alice Marble wrote an editorial for the July 1, 1950, edition of American Lawn Tennis Magazine:

"Miss Gibson is over a very cunningly wrought barrel, and I can only hope to loosen a few of its staves with one lone opinion. If tennis is a game for ladies and gentlemen, it's also time we acted a little more like gentlepeople and less like sanctimonious hypocrites …. If Althea Gibson represents a challenge to the present crop of women players, it's only fair that they should meet that challenge on the courts." Marble said that if Gibson were not given the opportunity to compete, "then there is an ineradicable mark against a game to which I have devoted most of my life, and I would be bitterly ashamed."[1]

Gibson was subsequently given the opportunity to participate in the 1950 U.S. Championships.

Gibson continued to improve her tennis game while pursuing an education. In 1953, she graduated from Florida A&M University on a tennis and basketball scholarship and moved to Jefferson City, Missouri to work as an athletic instructor at Lincoln University.

After having been given opportunities for integrated tournament play, Gibson was able to compete against the world's best players. In 1955, she won the Italian Championships, and in 1956, she won her first Grand Slam titles, capturing the French Championships in singles and in doubles with her partner, Jewish Englishwoman Angela Buxton. Buxton had run into discrimination from other players and the tennis establishment along the same lines as those experienced by Gibson, and found an empathetic ally in Gibson. The two noteworthy women formed a successful doubles tandem. An English newspaper reported their victory in 1956 at Wimbledon under the headline "Minorities Win." Their victory at Wimbledon made Buxton the first Jewish champion at Wimbledon, and Gibson the first champion of African descent. Their famous partnership would bring them two Grand Slam titles before Buxton was forced to retire at age 22 due to a serious hand injury.

In 1957, Gibson became the first black person to win the singles title at Wimbledon, defeating Darlene Hard in the final. She also defended her doubles title, this time partnering with Hard. Following the tournament, when she returned to the United States, Gibson was given a ticker-tape parade in New York City and an official welcome at New York City Hall. She went on to win the U.S. Championships that summer. For her accomplishments that year, Gibson earned the No. 1 ranking in the world and was named the Associated Press Female Athlete of the Year.

In 1958, after successfully defending her Wimbledon singles title and winning her third consecutive Wimbledon women's doubles title, Gibson again won the singles title at the U.S. Championships. She was named the Associated Press Female Athlete of the Year for the second consecutive year. It was also the year she retired from amateur tennis.

Before the open era of tennis began in 1968, players competed under amateur status, and did not receive endorsement deals or any prize money, other than an expense allowance. After her retirement, Gibson earned little from tennis, aside from a few exhibition tours, because at that time there was no professional tennis tour for women.

Golf

There was however a women's professional golf tour. In 1964 she became the first African-American woman to play in the Ladies Professional Golf Association.

Already in her late thirties when she turned to golf her best finish on the LPGA Tour came at the 1970 Len Immke Buick Classic, where she lost in a three-way playoff and tied for second. Gibson posted nine other top-10 finishes in her LPGA career. Over the course of her golf career, she earned $19,250.25, although she was one of the LPGA's top 50 money winners for five years.[2]

Retirement and later life

In later years, Gibson suffered two cerebral aneurysms and in 1992 she suffered a stroke. A few years later, she found herself still in poor health and living on welfare, unable to pay for rent or medication. She called her former doubles partner and lifelong friend Angela Buxton and told her she was on the brink of suicide. Buxton secretly arranged for a letter to appear in a tennis magazine to urge the world to help Gibson. Nearly $1 million was collected for Gibson from letters from around the world.[3]

Gibson died on September 28, 2003, in East Orange, New Jersey at the age of 76, due to respiratory failure. She was interred at the Rosedale Cemetery in Orange, New Jersey.

Gibson was married twice: to William Darben, married October 17, 1965 and divorced August, 1976; and to her former tennis coach, Sydney Llewellyn, married April 11, 1983, divorced after 3 years. She then rekindled her friendship with her first husband, and they remained close until his death. She had no children.

Legacy

In 1958, Gibson wrote her autobiography called I Always Wanted To Be Somebody. The following year, she recorded an album, Althea Gibson Sings, and appeared in the motion picture The Horse Soldiers.

In 1971, Gibson was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame and the International Women's Sports Hall of Fame in 1980. In 1975, she was appointed the New Jersey state commissioner of athletics, a position she would hold for ten years. She was the first woman in the nation to serve in such a position. Later, she served in other public service roles, including a position with the governor's council on physical fitness.

In 1991, the NCAA honored Gibson with the Theodore Roosevelt Award, the organization's highest honor. She was the first woman to ever receive it.

In 1988 she presented her Wimbledon trophies to the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History. In 2000 the National First Ladies' Library and the Smithsonian saluted Gibson at their Second Annual First Ladies Salute First Women awards dinner and cited her leadership in creating opportunities for minority athletes. Unable to attend the ceremony Ms. Fran Clayton-Gray, CEO of the Althea Gibson Foundation, received the award on her behalf. Gray, a longtime friend and co-founder of the Althea Gibson Foundation, said of Gibson, "Her contribution to the civil rights movement was done with her tennis racket."[4]

In 2001 the Wheaties ("Breakfast of Champions") cereal box featured a special-edition Black History Month package commemorating the career and accomplishments of Gibson at the Althea Gibson Early Childhood Academy in East Orange. The Wheaties package also featured information about the Althea Gibson Foundation that was established in 1998.

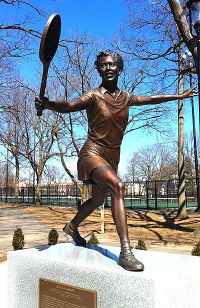

In 2018, the USTA unanimously voted to erect a statue honoring Gibson at Flushing Meadows, site of the US Open. That statue was unveiled in 2019.[5] Gibson's statue is only the second statue on the grounds of the U.S. Open erected in honor of a champion.

Grand Slam finals

Singles (7)

Wins (5)

| Year | Championship | Opponent in Final | Score in Final |

| 1956 | French Championships | 6-0, 12-10 | |

| 1957 | Wimbledon | 6-3, 6-2 | |

| 1957 | U.S. Championships | 6-3, 6-2 | |

| 1958 | Wimbledon (2) | 8-6, 6-2 | |

| 1958 | U.S. Championships (2) | 3-6, 6-1, 6-2 |

Runners-up (2)

| Year | Championship | Opponent in Final | Score in Final |

| 1957 | Australian Championships | 6-3, 6-4 | |

| 1956 | U.S. Championships | 6-3, 6-4 |

Doubles (11)

Wins (6)

| Year | Championship | Event | Partnering | Opponents in Final | Score/Final |

| 1956 | French Championships | Women's doubles | 6-8, 8-6, 6-1 | ||

| 1956 | Wimbledon | Women's doubles | 6-1, 8-6 | ||

| 1957 | Australian Championships | Women's doubles | 6-2, 6-1 | ||

| 1957 | Wimbledon (2) | Women's doubles | 6-1, 6-2 | ||

| 1957 | U.S. Championships | Mixed doubles | 6-3, 9-7 | ||

| 1958 | Wimbledon (3) | Women's doubles | 6-3, 7-5 |

Runners-up (5)

| Year | Championship | Event | Partnering | Opponents in Final | Score/Final |

| 1956 | Wimbledon | Mixed doubles | 2-6, 6-2, 7-5 | ||

| 1957 | Wimbledon | Mixed doubles | 6-4, 7-5 | ||

| 1957 | U.S. Championships | Women's doubles | 6-2, 7-5 | ||

| 1958 | Wimbledon | Mixed doubles | 6-3, 13-11 | ||

| 1958 | U.S. Championships | Women's doubles | 2-6, 6-3, 6-4 |

Grand Slam singles tournament timeline

| Tournament | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | Career SR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | F | A | 0 / 1 |

| France | A | A | A | A | A | A | W | A | A | 1 / 1 |

| Wimbledon | A | 3R | A | A | A | A | QF | W | W | 2 / 4 |

| United States | 2R | 3R | 3R | QF | 1R | 3R | F | W | W | 2 / 9 |

| SR | 0 / 1 | 0 / 2 | 0 / 1 | 0 / 1 | 0 / 1 | 0 / 1 | 1 / 3 | 2 / 3 | 2 / 2 | 5 / 15 |

A = did not participate in the tournament

SR = the ratio of the number of Grand Slam singles tournaments won to the number of those tournaments played

Notes

- ↑ Billie Jean King with Cynthia Starr, We Have Come a Long Way: The Story of Women's Tennis (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988, ISBN 0070346259), 76.

- ↑ Anya Alvarez, The lesser-known history of Althea Gibson the golfer ESPNW, February 20, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ↑ Nate Bloom, Celebrity Jews in the News Jweekly, October 10, 2003. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ↑ Deepti Hajela, Black Tennis Pioneer Althea Gibson Dies Associated Press, September 28, 2003. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ↑ Anne Branigin, Althea Gibson, the First Black Athlete to Integrate Tennis, Finally Gets Her Flowers With New Statue The Root, August 26, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gibson, Althea. I Always Wanted To Be Somebody. HarperCollins, 1958. ISBN 978-0060115159.

- Gray, Francis Clayton. Born To Win: The Authorized Biography of Althea Gibson. Wiley Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-0471471653.

- King, Billie Jean with Cynthia Starr. We Have Come a Long Way: The Story of Women's Tennis. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988. ISBN 0070346259.

- Schoenfeld, Bruce. The Match: Althea Gibson & Angela Buxton: How Two Outsiders—One Black, the Other Jewish—Forged a Friendship and Made Sports History. Amistad, 2004. ISBN 978-0060526528.

External links

All links retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Althea Gibson ThoughtCo.

- Black History Month Legends: Althea Gibson USTA.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.