Anarchist communism

| Communism |

| Basic concepts |

| Marxist philosophy |

| Class struggle |

| Proletarian internationalism |

| Communist party |

| Ideologies |

| Marxism Leninism Maoism |

| Trotskyism Juche |

| Left Council |

| Religious Anarchist |

| Communist internationals |

| Communist League |

| First International |

| Comintern |

| Fourth International |

| Prominent communists |

| Karl Marx |

| Friedrich Engels |

| Rosa Luxemburg |

| Vladimir Lenin |

| Joseph Stalin |

| Leon Trotsky |

| Máo Zédōng |

| Related subjects |

| Anarchism |

| Anti-capitalism |

| Anti-communism |

| Communist state |

| Criticisms of communism |

| Democratic centralism |

| Dictatorship of the proletariat |

| History of communism |

| Left-wing politics |

| Luxemburgism |

| New Class New Left |

| Post-Communism |

| Eurocommunism |

| Titoism |

| Primitive communism |

| Socialism Stalinism |

| Socialist economics |

Anarchist communism advocates the abolition of the state, private property, and capitalism in favor of common ownership or control of the means of production. Only through such collective control, it argues, can "the individual" be free of governmental domination and economic, that is, capitalist, exploitation. Under anarchist communism, the actual tasks of governance and production would be accomplished directly through a horizontal network of voluntary associations, workers' councils, and a gift economy from which everyone would partake solely to satisfy his or her real needs.

Anarchist communism, also known as anarcho-communism, communist anarchism, or sometimes, libertarian communism, advocates the abolition of government, which it refers to as the state; private property, especially the means and assets of mass production; and capitalism itself. In place of those institutions and systems, it calls for—as does its ideological competitor Marxism—common ownership or at least control of the means of production. Unlike Marxism, however, which advocates a dictatorship of the proletariat, anarchist communism opposes all bosses, hierarchy, and domination.

The utopian vision of anarchist communism is rooted in the positive value of the individual. It sees the society as nothing more than a collection of individuals and imagines that the interests of all the individuals can be coordinated successfully without the individual having to sacrifice any of his individual desire for the sake of the common good. It does not view the public or society as representing a higher good to which the individual must subordinate his or her interests.

Development of ideas

While some historians say the roots of anarchist theory can be traced to the ancient Greeks, including the founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium, who "proclaimed the … ideal of a free community without government,"[1] contemporary anarchist communist thought first took form during the English Civil War and the French Revolution of the 1700s.

Gerrard Winstanley, who was part of the radical Diggers movement in England—a group of destitute peasants who began to cultivate common land—wrote in his 1649 pamphlet, The New Law of Righteousness, that there "shall be no buying or selling, no fairs nor markets, but the whole earth shall be a common treasury for every man," and "there shall be none Lord over others, but every one shall be a Lord of himself."[2] During the French Revolution, Sylvain Maréchal, in his Manifesto of the Equals (1796), demanded "the communal enjoyment of the fruits of the earth" and looked forward to the disappearance of "the revolting distinction of rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed."[2]

As anarchist thought evolved, a split began to form between those who, like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, felt that workers had a right to collectively own their own product, and those who argued that workers' needs, not their production, should be the basis of a free society. A nineteenth century anarchist communist, Joseph Déjacque, the first person to describe himself as "libertarian," argued that, "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature."[2]

Later, a group of radicals known as collectivist anarchists, led by Mikhail Bakunin, argued against the anarcho-communist view of "to each according to need." Instead, they felt workers should be paid for their labor based on how much time they contributed. Still, they held out the possibility of a post-revolutionary transition to a communist system of distribution according to need. It would be made possible, they felt, given the superior capacity of collective production. As Bakunin's associate, James Guillaume, put it in his essay, Ideas on Social Organization (1876), "When… production comes to outstrip consumption… [e]veryone will draw what he needs from the abundant social reserve of commodities, without fear of depletion; and the moral sentiment which will be more highly developed among free and equal workers will prevent, or greatly reduce, abuse and waste."[3]

Bakunin became an anarchist later in his life, and his methods for realizing his revolutionary program were rooted in his belief that the workers and peasants were to organize on a federalist basis, "creating not only the ideas, but also the facts of the future itself.[4] The worker's trade union associations would "take possession of all the tools of production as well as buildings and capital.[5] Based on his experience of the Russian aristocracy and the system of serfdom, and particularly the Russian peasant commune, or мир (mir). During the nineteenth century, the Russian system became increasingly anarchronistic, and the attempts to create a civil service removed many of the aristocrats from their estates, leaving the peasants to run the affairs. The peasants ultimately felt that the landlords were no longer needed. Bakunin theorized that the peasants should "take the land and throw out those landlords who live by the labor of others."[6] Bakunin looked to "the rabble," the great masses of the poor and exploited, the so-called "lumpenproletariat," to "inaugurate and bring to triumph the Social Revolution," as they were "almost unpolluted by bourgeois civilization."[7]

First International

The dispute enabled anarchist communism to emerge as a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy in the Italian section of the First International by Carlo Cafiero, Errico Malatesta, Andrea Costa and other ex-Mazzinian Republicans. At the time, Bakunin and the collectivist anarchists sought to socialize ownership of the means of production while retaining payment for labor, but the anarcho-communists sought to extend the concept of collective ownership to the products of labor as well. While both groups opposed capitalism, the anarchist communists proposed that individuals should be free to access goods according to their needs without respect to how much labor they exert.

Cafiero explained the opposition to ownership in Anarchy and Communism (1880), arguing that private property in the product of labor will lead to unequal accumulation of capital and, therefore, undesirable class distinctions: "If we preserve the individual appropriation of the products of labour, we would be forced to preserve money, leaving more or less accumulation of wealth according to more or less merit rather than need of individuals."[2] At the Florence Conference of the Italian Federation of the International in 1876, held in a forest outside Florence for fear of the police, they declared the principles of anarcho-communism, beginning with:

The Italian Federation considers the collective property of the products of labour as the necessary complement to the collectivist program, the aid of all for the satisfaction of the needs of each being the only rule of production and consumption which corresponds to the principle of solidarity. The federal congress at Florence has eloquently demonstrated the opinion of the Italian International on this point….

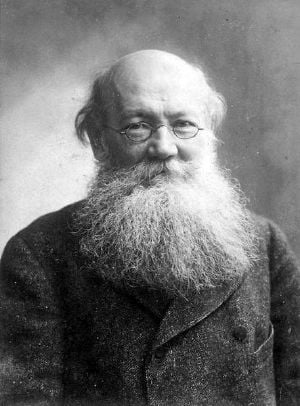

Peter Kropotkin

Peter Kropotkin, a scion of the Russian aristocracy, is often seen as the most important theorist of anarchist communism. In The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops, Kropotkin felt that co-operation is more beneficial than competition, arguing in Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution that nature itself proved the point. He advocated the abolition of private property through the "expropriation of the whole of social wealth" by the people themselves,[8] and for the economy to be co-ordinated through a horizontal or non-hierarchical network of voluntary associations, where goods are distributed according to the physical needs of the individual, rather than according to labor.[9]

He further argued that these "needs," as society progressed, would not merely be physical needs but "[a]s soon as his material wants are satisfied, other needs, of an artistic character, will thrust themselves forward the more ardently. Aims of life vary with each and every individual; and the more society is civilized, the more will individuality be developed, and the more will desires be varied."[9]

Kropotkin maintained that, in anarcho-communism:

…houses, fields, and factories will no longer be private property, and that they will belong to the commune or the nation and money, wages, and trade would be abolished.[9]

Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed, as the aim of anarchist communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home."[10] Central to his advocacy of the expropriation of property was his desire to ensure that all would have access to what they needed without being forced to sell their labor to get it. In other words, he saw fulfillment of needs as a human birthright.

We do not want to rob any one of his coat, but we wish to give to the workers all those things the lack of which makes them fall an easy prey to the exploiter, and we will do our utmost that none shall lack aught, that not a single man shall be forced to sell the strength of his right arm to obtain a bare subsistence for himself and his babes. This is what we mean when we talk of Expropriation… [9]

He also said that a "peasant who is in possession of just the amount of land he can cultivate," and "a family inhabiting a house which affords them just enough space… considered necessary for that number of people" and the artisan "working with their own tools or handloom" would not be interfered with, arguing that "[t]he landlord owes his riches to the poverty of the peasants, and the wealth of the capitalist comes from the same source."[11]

Over the ensuing years, while many anarcho-communists remained opposed to trade, some post-left and post-scarcity anarcho-communists, and those who favored syndicalism—a largely defunct direct action movement advocating a social order based on worker-organized production units—have shed that opposition. Some support a non-monetary form of trade such as barter. Others say anarcho-communism is compatible with a non-hierarchical, open access, free association, non-monetary form of trade such as P2P, or peer-to-peer computer file sharing.[12]

Socio-economic theory

Anarchist communism stresses egalitarianism and the abolition of social hierarchy and class distinctions that arise from unequal wealth distribution, as well as the abolition of private property and money. In their stead would be collective production and distribution of wealth via voluntary associations. In anarchist communism, the state and private property would no longer exist. All individuals and groups would be free to contribute to production and to satisfy their needs based on their own choice. Systems of production and distribution would be managed by their participants.

The abolition of wage labor is central to anarchist communism. If distribution of wealth is based on self-determined needs, people would be free to engage in whatever activities they found most fulfilling and would no longer have to do work for which they have neither the temperament nor the aptitude. Anarchist communists argue that there is no valid way of measuring the value of any one person's economic contributions because all wealth is a collective product of current and preceding generations. For instance, one could not measure the value of a factory worker's daily production without taking into account how transportation, food, water, shelter, relaxation, machine efficiency, emotional mood, and other contributions to their production. To give a valid numerical economic value to anything, an overwhelming amount of external factors would need to be taken into account—especially current or past labor contributing to the ability to utilize future labor.

Anarchist communists argue that any economic system based on wage labor and private property requires a coercive state apparatus to enforce property rights and to maintain unequal economic relationships that inevitably arise from differences in wages or ownership of property. They argue further that markets and systems of currency divide labor into classes, assigning artificial numerical values to an individual's work, and attempting to regulate production, consumption and distribution. They maintain that money restricts an individual's ability to consume the products of his or her labor by limiting intake with prices and wages. Anarchist communists view money as fundamentally quantitative in nature, rather than qualitative. In contrast, under capitalism, money is viewed as society's primary measure of value, qualitative and quantitative.

Production, anarcho-communists argue, should be a qualitative matter. Further, consumption and distribution should be self-determined by each individual without arbitrary value assigned to labor, goods and services by others. In place of a market, most anarcho-communists support a currency-less gift economy in which goods and services are produced by workers and distributed in community stores where everyone (including the workers who produced them) is essentially entitled to consume whatever he or she wants or needs as "payment" for producing. A gift economy does not necessarily involve an immediate return; compensation comes in the form of whatever the person decides is of equal value to his or her products of labor (what is commonly called bartering). Any limits on production and distribution would be determined by the individuals within the groups involved, rather than by capitalist owners, investors, banks or other artificial market pressures.

Land and housing, being socially owned, would no longer be subject to rent or property taxes (and therefore, occupants would be free of eviction threats). Occupants would instead be subject simply to their own collective desires, manifested on an egalitarian basis. Thus, in a multi-unit apartment building, no one person would determine management issues. All who live there would be involved in decision making.

Crucially, the relationship of "landlord" and "tenant" would no longer exist, for such titles are seen as merely a form of legal coercion; they are not inherently necessary to occupy buildings or spaces. (Intellectual property rights would also cease.) In addition to believing rent and other fees are exploitative, anarcho-communists feel these are arbitrary pressures inducing people to carry out unrelated functions. For example, they question why one should have to work for "X hours" a day to merely live somewhere. Instead of working to earn a wage, they believe in working directly for the objective at hand. So, rather than land being for sale or rent, vacant land and housing would be freely taken regardless of one's employment or financial status (essentially, the "for sale" sign could be replaced by a "vacant" sign).

Therefore, in anarcho-communist theory, land used by individuals for themselves or their families, or productive property used to produce for an individual (such as a small farm), would be considered personal possessions rather than social possessions. The individual would remain free to create something and keep it as long as it is not crucial to the means of production for the community or general public. So an artist, for example, would not need outside approval to use paintbrushes. The same basic principle would apply to other personal items such as one's toothbrush, musical instruments or book collection. However, if the possession involves production for society (such as a factory that makes toothbrushes, musical instruments or books), it would be considered a social possession, accountable to all who work within it and to the consuming public. In that regard, anarcho-communism can be seen as a compromise between collective and individual use.[11]

Anarcho-communists also reject mutualist economics—a non-capitalist market economy characterized by free association of workers; socially owned banks or credit unions for free credit; goods exchanged solely for cost rather than profit (an arrangement defined as contract, or federation); and gradualism instead of revolution. Their rejection is based on the belief that market competition, even a non-capitalist market, inherently creates inequalities in wealth and land which generate inequalities of power—thus leading to the recreation of the state and capitalism, as some workers would have more access to capital and defense forces than others. They reject the collectivist anarchist view of remuneration, arguing that payment for labor would require a type of currency, which, again, anarcho-communists reject as an artificial measurement of the value of labor.

In terms of human nature, anarchist communists reject the claim that wage labor is necessary because people are inherently lazy and selfish. They generally do not agree with the belief in a pre-set "human nature," arguing that culture and behavior are largely determined by socialization. Many, like Peter Kropotkin, also believe that, in the course of evolution, humans progress by cooperating with each other for mutual benefit and survival, instead of attempting to survive as lone competitors.[13]

Criticisms and anarcho-communist responses

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, whose philosophy has influenced social anarchists[9] (including social Christian anarchist Leo Tolstoy [14]), was critical of communism, "whether of the Utopian or the Marxist variety, [believing] that it destroyed freedom by taking away from the individual control over his means of production." At the time he wrote most of his works, the word "communism" was typically used to refer to the views of the Utopian socialists, whom Proudhon accused of attempting to impose equality by sovereign decrees. In opposition to the communist maxim "to each according to need," Proudhon said "To each according to his works, first; and if, on occasion, I am impelled to aid you, I will do it with a good grace; but I will not be constrained."[15] However, Proudhon was against the hoarding of private property in an unequal society and thus supported equality of condition, which he believed would negate the difference in amounts of private property.

In his treatise What is Property?(1849), Proudhon answers with "Property is theft!"[16] He sees two conceivable types of property: de jure and de facto, and argues that the former is illegitimate. Proudhon's fundamental premise is that equality of condition is the essence of justice. "By this method of investigation, we soon see that every argument which has been invented in behalf of property, whatever it may be, always and of necessity leads to equality; that is, to the negation of property."[16] He argued that inequality in society would impoverish some people at the hands of people with more land:

The purchaser draws boundaries, fences himself in, and says, "This is mine; each one by himself, each one for himself." Here, then, is a piece of land upon which, henceforth, no one has right to step, save the proprietor and his friends; which can benefit nobody, save the proprietor and his servants. Let these multiply, and soon the people … will have nowhere to rest, no place of shelter, no ground to till. They will die of hunger at the proprietor's door, on the edge of that property which was their birth-right; and the proprietor, watching them die, will exclaim, "So perish idlers and vagrants."[16]

Proudhon was also opposed to capitalism. For him, the capitalist's employee was "subordinated, exploited: His permanent condition is one of obedience."[17] Proudhon called himself a "socialist" and called his philosophy "anarchist socialism." He opposed state ownership of capital goods in favor of ownership by workers themselves in associations.

Individualist anarchism

Many individualist anarchists believe that elements of anarcho-communism are undesirable or even incompatible with anarchism itself. Benjamin Tucker referred to anarcho-communism as "pseudo-anarchism"[18] when admonishing Peter Kropotkin for opposing wages. Henry Appleton said: "All Communism, under whatever guise, is the natural enemy of Anarchism, and a Communist sailing under the flag of Anarchism is as false a figure as could be invented."[19]

The mutualist Clarence Lee Swartz says in What is Mutualism: "One of the tests of any reform movement with regard to personal liberty is this: Will the movement prohibit or abolish private property? If it does, it is an enemy of liberty. For one of the most important criteria of freedom is the right to private property in the products of one's labor. State Socialists, Communists, Syndicalists and Communist-Anarchists deny private property." William Kline says that the individualists and communists "could not reconcile their differences, the Communist Anarchists dedicated to a community of property and the Individualist Anarchists deeply committed to private property and individual effort."[20]

Anarcho-communists counter these criticisms by arguing that the abolition of property creates maximum freedom for all individuals. As Errico Malatesta argues,

The individualists assume … that the (anarchist) communists wish to impose communism, which of course would put them right outside the ranks of anarchism.

The communists assume … that the (anarchist) individualists reject every idea of association, want the struggle between men, the domination of the strongest—and this would put them not only outside the anarchist movement but outside humanity.

In reality those who are communists are such because they see in common freely accepted the realization of brotherhood, and the best guarantee for individual freedom. And individualists, those who are really anarchists, are anti-communist because they fear that communism would subject individuals … to the tyranny of the collectivity…. Therefore they want each individual, or each group, to be in a position to enjoy freely the product of their labour in conditions of equality with other individuals and groups, with whom they would maintain relations of justice and equity.

In which case it is clear that there is no basic difference between us. But, according to the communists, justice and equity are, under natural conditions impossible of attainment in an individualistic society, and thus freedom too would not be attained.

If climatic conditions throughout the world were the same, if the land were everywhere equally fertile, if raw materials were evenly distributed and within reach of all who needed them, if social development were the same everywhere in the world … then one could conceive of everyone … finding the land, tools and raw materials needed to work and produce independently, without exploiting or being exploited. But natural and historical conditions being what they are, how is it possible to establish equality and justice between he who by chance finds himself with a piece of arid land which demand much labour for small returns with him who has a piece of fertile and well sited land?[21]

Anarcho-communists also argue against mutualism, in that individual worker cooperatives have the potential to isolate and control those who do not belong to such institutions, or those with less money. In general, they maintain that the value of labor is subjective and thus cannot be measured by any monetary means, arguing that such values are arbitrary and lead to a stratification in society by a division of labor. Kropotkin and other communists anarchists have argued that the existence of defense [often spelled defense]) associations, even worker-owned ones that are freely available for everyone, have authoritarian implications, "[f]or their self-defense, both the citizen and group have a right to any violence [within individualist anarchy]… Violence is also justified for enforcing the duty of keeping an agreement. Tucker … opens … the way for reconstructing under the heading of the 'defense' all the functions of the State."[22] Moreover, anarcho-communists argue that even in a socialistic market such as in individualist and mutualist anarchy, as some workers reaped more revenue than others, due to different productivity in market competition, those with more money would have more access to capital (means of production) and thus become able to unilaterally influence market deals, decision-making and employment, offering the highest bids to defense firms and thus reconstituting capitalism and the State. Communist anarchist Albert Metzer harshly argued, "the school of Benjamin Tucker—by virtue of their individualism—accepted the need for police to break strikes so as to guarantee the employer's 'freedom.' All this school of so-called Individualists accept … the necessity of the police force, hence for government, and the prime definition of anarchism is no government." [23]

One capitalist criticism of anarcho-communism is that such a society would not be able to keep productivity up because individuals would not be paid for their labor, since wages would be abolished and people would instead be given things "according to their needs."[24]

In response, Anarchist communists today point to successful anarchic communes in Spain during the Spanish civil war that increased production significantly after eliminating capitalism's middlemen (see below). Traditionally, they argue that all theories of monetary value are subjective, that private property is inherently exploitative,[39] and that by making productive property freely accessible to all, it would increase individual liberty. They argue that labor should not be an obligation and should be a voluntary task that should be enjoyable or provide necessary services.

Marxism

Marxists criticize anarchism as incapable of creating a successful and lasting revolution because it is philosophically flat-footed and does not aptly identify issues of class and modes of production.[25] Both Marxist and anarchist class analyses are based on the idea that society is divided into many different "classes," each with differing interests according to their material circumstances. The two differ, however, in where they draw the lines between these groups. For Marxists, the two most relevant classes are the "bourgeoisie" (owners of the means of production) and the "proletariat" (wage laborers).

Anarchists argue that it is not the capital class that actually has control over the state, but another upper segment which is part of the ruling class but with its own concerns, particularly retaining political power, national territory and military power. Further, a revolutionary minority taking over state power and imposing its will on the people—Marxism's "vanguard"—would be just as authoritarian as the ruling minority in capitalism, and would eventually constitute itself as a ruling class since the class that governs the state is seen as separate from the labor class. This was predicted by Bakunin long before the Russian Revolution and the fall of the Soviet Union, when he wrote:

If you took the most ardent revolutionary, vested him in absolute power, within a year he would be worse than the Czar himself.[26]

Unlike Marxists, anarchists do not differentiate between peasants, lumpen-proletariat, merchants, some small business owners, and proletarians (workers). Instead, they define all people who work for the profit of others or sell the products of their own labor as members of the working class, regardless of occupation.[16] However, anarchists do differentiate between the economic and political elites who set policy and the business and government functionaries that carry those policies out, whereas Marxists lump the two together.[21] Further, some anarchists argue that Marxism fails because it springs from the minds of middle class intellectuals, while anarchism springs spontaneously from the self-activity and self-organization of the labor class.[27] They point to the fact that schools of Marxism are often named after the intellectuals who formed the movements through high analytical and philosophical theory's of praxis. Marxists respond that their ideas are not new ideologies which sprang from intellectuals but are ideas which form from the class contradictions of each economic and social mode of history.

It should be noted that these disagreements are less of a problem for libertarian Marxists who believe that a State apparatus should operate on proletariat-controlled basis—participatory democracy—or even as a consociational state. Marxists and anarcho-communists would both agree that it is the class division of society which gives rise to the state, because the minority need a special force to maintain their rule over the majority.

Despite criticisms, anarchist communist communes, such as anarchist Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War, saw increased productivity. The production of potatoes increased 50 percent and the production of sugar beets and feed for livestock doubled. Through the use of more modernized machinery and chemical fertilizers, the yield per hectare was 50 percent greater on collective property than on individually-owned land. The anarchist collectivization in Spain also showed that such ideas are possible to implement in industrial settings. 75 percent of Spanish industry was located in the Catalon region. According to local sources at the time:

Catalonia and Aragon, were about 70 per cent of the workforce was involved. The total for the whole of Republican territory was nearly 800,000 on the land and a little more than a million in industry. In Barcelona workers' committees took over all the services, the oil monopoly, the shipping companies, heavy engineering firms such as Volcano, the Ford motor company, chemical companies, the textile industry and a host of smaller enterprises… Services such as water, gas and electricity were working under new management within hours of the storming of the Atarazanas barracks … a conversion of appropriate factories to war production meant that metallurgical concerns had started to produce armed cars by 22 July… The industrial workers of Catalonia were the most skilled in Spain… One of the most impressive feats of those early days was the resurrection of the public transport system at a time when the streets were still littered and barricaded.[28]

The collectivist projects were quite successful, sources noted

In distribution the collectives' co-operatives eliminated middlemen, small merchants, wholesalers, and profiteers, thus greatly reducing consumer prices. The collectives eliminated most of the parasitic elements from rural life, and would have wiped them out altogether if they were not protected by corrupt officials and by the political parties. Non-collectivised areas benefited indirectly from the lower prices as well as from free services often rendered by the collectives (laundries, cinemas, schools, barber and beauty parlors, etc.).[29]

Historic examples

Several attempts, both successful and unsuccessful, have been made at creating anarchist communist societies in various areas of the world. The egalitarian nature of most hunter gatherer societies have led some anarchist communists and green anarchists (especially anarcho-primitivists) to argue that hunter gatherer tribes were the early forms of anarchist communism. Early Christian communities have been described by Christian anarchists and some historians as possessing anarcho-communist characteristics.

Egalitarian religious communities such as the Diggers Movement during the English Revolution could arguably be the first anarchist communist societies in modern history. Large communities and federations of communities such as Anarchist Catalonia and the Free Territory of revolutionary Ukraine are examples of successful anarchist-communism in twentieth century Europe. The free territories of Hungary during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 may be seen as another example of large-scale successful anarcho-communism.

On a less lauditory note, Luigi Galleani, an Italian anarcho-communist, inspired a terror bombing campaign in the United States that continued from 1914 to 1932.

The Korean Anarchist Movement in North and South Korea led by Kim Jwa Jin showed a temporary success in bringing anarcho-communism to Korea. However, the success was short-lived and not nearly as widely spread as the anarchism in Spain or Hungary. Some consider the current existing anarchist nature of communities in Argentina and the Zapatista councils in Mexico to be anarcho-communist in nature. Others consider them to be collectivist or syndicalist.

Current examples

Today, some anarcho-communists argue that a prime example of their ideology in practice is the traditional family. Each member contributes income purely by altruism, they say. Property is commonly owned, and the family has no internal price system—a major feature of anarcho-communism.

Some parts of the free software community, the GNU movement and parts of the copyleft movement reflect a type of information and software gift economy, which is also central to anarcho-communist ideology. Programmers make their source code available, allowing anyone to copy and modify/improve it. Individual programmers gain prestige and respect, and the community as a whole benefits from better software. Markus Giesler in his ethnography "Consumer Gift Systems" has developed music downloading as a system of social solidarity based on gift transactions.[30]

Notes

- ↑ Leonard Krimerman and Lewis Perry (eds.), Patterns of Anarchy (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1966, ISBN 978-0384599352).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Robert Graham, Anarchism—A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas - Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300C.E. to 1939) (Black Rose Books, 2005, ISBN 9781551642505).

- ↑ James Guillaume, Ideas on Social Organization. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Mikhail Bakunin, The Structure of the International Bakunin on Anarchy, translated and edited by Sam Dolgoff, 1971. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Mikhail Bakunin, Letter to Albert Richard, Bakunin on Anarchy, translated and edited by Sam Dolgoff, 1971. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Mikhail Bakunin, Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis Bakunin on Anarchy, translated and edited by Sam Dolgoff, 1971. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Mikhail Bakunin, On the International Workingmen's Association and Karl Marx, 1872, Bakunin on Anarchy, translated and edited by Sam Dolgoff, 1971. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Peter Kropotkin, Words of a Rebel (Black Rose Books, 1992, ISBN 978-1895431049).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread (Read & Co. Great Essays, 2020, ISBN 978-1528772426).

- ↑ Peter Kropotkin, The Place of Anarchism in the Evolution of Socialist Thought (Read & Co. Books, 2020, ISBN 978-1528716017).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Peter Kropotkin, N. Walter Alekseevich and H. Becker (eds.), Act for Yourselves (London: Freedom Press, 1985, ISBN 9780900384387).

- ↑ Tiziana Terranova, Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy Social Text 63 18(2) (Summer 2000):33-58. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution Anarchy Archives. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Jack Hayward, After the French Revolution: Six Critics of Democracy and Nationalism (New York University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0814734803).

- ↑ Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, The System of Economical Contradictions; Or, the Philosophy of Misery (Dodo Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1409979739).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Donald R. Kelley and Bonnie G. Smith (eds.), Proudhon: What is Property? (Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 0521405564).

- ↑ Pierre Joseph Proudhon, General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century (1851), Sixth Study, § 3 ¶ 5. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Benjamin Tucker, Individual Liberty The Anarchist Library. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Henry Appleton, Anarchism, True and False (1884) Molinari Institute. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ William Kline, The Individualist Anarchists: A Critique of Liberalism (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1987, ISBN 9780819163967).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Errico Malatesta, Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas (London: Freedom Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0900384158).

- ↑ Peter Kropkotkin, Kropotkin's Revolutionary Pamphlets (Dover Publications, 1971, ISBN 978-0486225197).

- ↑ Albert Metzer, Anarchism: Arguments For and Against (San Francisco: AK Press, 2001, ISBN 1873176570).

- ↑ Donald F. Busky, Communism in History and Theory: From Utopian Socialism to the Fall of the Soviet Union (Praeger/Greenwood, 2002, ISBN 9780275979546).

- ↑ David McNally, Socialism From Below (Socialist Workers' Party, 1984, ISBN 978-0905998459).

- ↑ Daniel Guérin, Anarchism: From Theory to Practice (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1970, ISBN 978-0853451280).

- ↑ Michael Bakunin, Selected Writings (Red and Black Publishers, 2010, ISBN 978-1934941836).

- ↑ Antony Beevor, The Spanish Civil War (Penguin Books, 2001, ISBN 978-0141001487).

- ↑ Jose Peirats, The Revolution on the Land The Anarchist Collectives. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ↑ Countless Exchanges in the Gift Economy: Toward a New Understanding of Transactions Transaction.net. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bakunin, Michael. Selected Writings. Red and Black Publishers, 2010. ISBN 978-1934941836

- Beevor, Antony. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0141001487

- Busky, Donald F. Communism in History and Theory: From Utopian Socialism to the Fall of the Soviet Union. Praeger/Greenwood, 2002. ISBN 9780275979546

- Graham, Robert. Anarchism—A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas—Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300C.E. to 1939). Black Rose Books, 2005. ISBN 9781551642505

- Guérin, Daniel. Anarchism: From Theory to Practice. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0853451280

- Hayward, Jack. After the French Revolution: Six Critics of Democracy and Nationalism. New York University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0814734803

- Kline, William. The Individualist Anarchists: A Critique of Liberalism. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1987. ISBN 9780819163967

- Krimerman, Leonard, and Lewis Perry (eds.). Patterns of Anarchy. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1966. ISBN 978-0384599352

- Kropotkin, Peter, N. Walter Alekseevich and H. Becker (eds.). Act for Yourselves. London: Freedom Press, 1985. ISBN 9780900384387

- Kropotkin, Peter. Words of a Rebel. Black Rose Books, 1992. ISBN 978-1895431049

- Kropotkin, Peter. The Conquest of Bread. Read & Co. Great Essays, 2020. ISBN 978-1528772426

- Kropotkin, Peter. The Place of Anarchism in the Evolution of Socialist Thought. Read & Co. Books, 2020. ISBN 978-1528716017

- Kropkotkin, Peter. Kropotkin's Revolutionary Pamphlets. Dover Publications, 1971. ISBN 978-0486225197

- Malatesta, Errico. Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas. London: Freedom Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0900384158

- McNally, David. Socialism From Below. Socialist Workers' Party, 1984. ISBN 978-0905998459

- Metzer, Albert. Anarchism: Arguments For and Against. San Francisco: AK Press, 2001. ISBN 1873176570

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. The System of Economical Contradictions; Or, the Philosophy of Misery. Dodo Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1409979739

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph, Donald R. Kelley and Bonnie G. Smith (eds.). Proudhon: What is Property? Cambridge University Press, 1994,. ISBN 0521405564

External links

All links retrieved July 26, 2023.

- "Communism: what's in a word?"

- Anarkismo.net - Anarchist communist news, discussion and theory from across the globe

- libcom.org - The home of anarchism and libertarian communism in the UK

- Anarchist Federation - Anarchist communist organization in Britain

- Workers Solidarity Movement - Anarchist communist organization in Ireland

- Federazione dei Comunisti Anarchici (FdCA) (in Italian)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.