Aneurin Bevan

| Aneurin Bevan | |

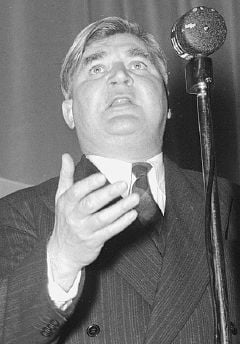

Aneurin Bevan, 1952 | |

Deputy Leader of the Labour Party

| |

| In office May 4, 1959 â July 6, 1960 | |

| Preceded by | Jim Griffiths |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | George Brown |

Shadow Foreign Secretary

| |

| In office July 22, 1956 â May 4, 1959 | |

| Preceded by | Alf Robens |

| Succeeded by | Denis Healey |

Minister of Labour and National Service

| |

| In office January 17, 1951 â April 23, 1951 | |

| Prime Minister | Clement Attlee |

| Preceded by | George Isaacs |

| Succeeded by | Alf Robens |

Minister of Health

| |

| In office August 3, 1945 â January 17, 1951 | |

| Prime Minister | Clement Attlee |

| Preceded by | Henry Willink |

| Succeeded by | Hilary Marquand |

Member of Parliament

for Ebbw Vale | |

| In office May 31, 1929 â July 6,1960 | |

| Preceded by | Evan Davies |

| Succeeded by | Michael Foot |

| Born | November 15 1897 Tredegar, Monmouthshire, Wales |

| Died | July 6 1960 (aged 62) Chesham, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Political party | Labour Party |

| Spouse | Jennie Lee (m. 1934) |

| Alma mater | Central Labour College, London |

Aneurin Bevan, usually known as Nye Bevan (November 15, 1897 â July 6, 1960) was a Welsh Labour politician. He was a key figure on the left of the party in the mid-twentieth century and was the Minister of Health responsible for the formation of the National Health Service (NHS). He became Deputy Leader of the Labour Party in 1959, but died of cancer the following year. Although he did not become Prime Minister, he counts as one of the most significant British politicians of the twentieth century whose legacy has impacted the lives of millions. The NHS is considered by some to be the finest achievement in post-World War II Britain. He brought an almost religious Welsh-style passion and fervor to politics. For him and for many in the Labour Party at this time, winning the battle against Nazi tyranny was meaningless unless people's lives improved and being free had real value. Universal access to health care free at the point of delivery, which was for him an "almost religious belief"[1] was an essential part of the new society he and others wanted to build.

Having left school at 13 he yet made a significant ideological contribution to British socialism represented by his writing and speeches. On the one hand, he was a class warrior who did not hesitate to cite Karl Marx and supported recognition of China under Mao Zedong. On the other hand, he did not share the bitterness of some fellow socialists who despised the elite. Characteristically, he was generous and optimistic about the possibility of human altruism. Certainly ambitious, he was motivated by the desire to improve the lives of his own class and knew that to do so he had to gain political office, if not power.[1] His new society would have little place for privilege but neither would it be exclusive. He wanted a better world for everyone. Known as a rebel, it has been suggested that this explains why he did not become Party Leader. Yet, while he was denied the promotion he almost certainly deserved, he used his skills and passion to make the world a better place. His religion has been described as love of others and as the desire to serve them.[2]

Youth

Bevan was born in Tredegar, Monmouthshire, in the South Wales Valleys and on the northern edge of the South Wales coalfield, the son of miner David Bevan. Both Bevan's parents were Nonconformists; his father was a Baptist and his mother a Methodist. One of ten children, Bevan did poorly at school and his academic performance was so bad that his headmaster made him repeat a year. At age 13, Bevan left school and began working in the local Tytryst Colliery. David Bevan had been a supporter of the Liberal Party in his youth, but was converted to socialism by the writings of Robert Blatchford in the Clarion and joined the Independent Labour Party.

His son also joined the Tredegar branch of the South Wales Miners' Federation and became a trade union activist: he was head of his local Miners' Lodge at only 19. Bevan became a well-known local orator and was seen by his employers, the Tredegar Iron & Coal Company, as a revolutionary. He was always arguing with the supervisors.[3] He avoided conscription during World War I due to nystagmus and was critical of the simplistic view of the war as a fight between good and evil, suggesting that it was more complex than this. The manager of the colliery found an excuse to get him sacked. But, with the support of the Miners' Federation, the case was judged as one of victimization and the company was forced to re-employ him.

In 1919, he won a scholarship to the Central Labour College in London, sponsored by the South Wales Miners' Federation. At the college, he gained his life-long respect for Karl Marx. Reciting long passages by William Morris, Bevan gradually began to overcome the stammer that he had since he was a child.

Upon returning home in 1921, he found that the Tredegar Iron & Coal Company refused to re-hire him. He did not find work until 1924, in the Bedwellty Colliery, and it closed down after ten months. Bevan had to endure another year of unemployment and in February 1925, his father died of pneumoconiosis.

In 1926, he found work again, this time as a paid union official. His wage of ÂŁ5 a week was paid by the members of the local Miners' Lodge. His new job arrived in time for him to head the local miners against the colliery companies in what would become the General Strike. When the strike started on May 3, 1926, Bevan soon emerged as one of the leaders of the South Wales miners. The miners remained on strike for six months. Bevan was largely responsible for the distribution of strike pay in Tredegar and the formation of the Council of Action, an organization that helped to raise money and provided food for the miners.

He was a member of the Cottage Hospital Management Committee around 1928 and was chairman in 1929/30.

Parliament

In 1928, Bevan won a seat on Monmouthshire County Council. With that success he was picked as the Labour Party candidate for Ebbw Vale (displacing the sitting MP), and easily held the seat at the 1929 General Election. In Parliament, he soon became noticed as a harsh critic of those he felt opposed the working man. His targets included the Conservative Winston Churchill and the Liberal Lloyd George, as well as Ramsay MacDonald and Margaret Bondfield from his own Labour party (he targeted the latter for her unwillingness to increase unemployment benefits). He had solid support from his constituency, being one of the few Labour MPs to be unopposed in the 1931 General Election.

Soon after he entered parliament, Bevan was briefly attracted to Oswald Mosley's arguments, in the context of Macdonald's government's incompetent handling of rising unemployment. However, in the words of his biographer John Campbell, "he breached with Mosley as soon as Mosley breached with the Labour Party." This is symptomatic of his lifelong commitment to the Labour Party, which was a result of his firm belief that only a Party supported by the British Labour Movement could have a realistic chance of attaining political power for the working class. Thus, for Bevan, joining Mosley's New Party was not an option. Bevan is said to have predicted that Mosley would end up as a Fascist. His passion and gift for oratory made him a popular speaker, often attracting thousands at rallies while members of Parliament would "go into the chamber just to hear him speak."[4] He was not "flamboyant ⌠but could hold the house in his spell."[5]

He married fellow socialist MP Jennie Lee in 1934. He was an early supporter of the socialists in Spain and visited the country in the 1930s. In 1936, he joined the board of the new socialist newspaper the Tribune. His agitations for a united socialist front of all parties of the left (including the Communist Party of Great Britain) led to his brief expulsion from the Labour Party in March to November 1939 (along with Stafford Cripps and C.P. Trevelyan). But, he was readmitted in November 1939, after agreeing "to refrain from conducting or taking part in campaigns in opposition to the declared policy of the Party."[6]

He was a strong critic of the policies of Neville Chamberlain, arguing that his old enemy Winston Churchill should be given power. During the war he was one of the main leaders of the left in the Commons, opposing the wartime Coalition government. Bevan opposed the heavy censorship imposed on radio and newspapers and wartime Defence Regulation 18B, which gave the Home Secretary the powers to intern citizens without trial. Bevan called for the nationalization of the coal industry and advocated the opening of a Second Front in Western Europe in order to help the Soviet Union in its fight with Germany. Churchill responded by calling Bevan "⌠a squalid nuisance."[7]

Bevan believed that the Second World War would give Britain the opportunity to create "a new society." He often quoted an 1855 passage from Karl Marx: "The redeeming feature of war is that it puts a nation to the test. As exposure to the atmosphere reduces all mummies to instant dissolution, so war passes supreme judgment upon social systems that have outlived their vitality."[8] At the beginning of the 1945 general election campaign Bevan told his audience: "We have been the dreamers, we have been the sufferers, now we are the builders. We enter this campaign at this general election, not merely to get rid of the Tory majority. We want the complete political extinction of the Tory Party."[9]

After World War II, when the Communists took control of China. Parliament debated the merits of recognizing the Communist government. Churchill, no friend of Bevan or Mao Zedong, commented that recognition would be advantageous to the United Kingdom for various reasons and added, "if you recognize anyone, it does not mean that you like them. We all, for instance, recognize the right honorable gentleman, the member for Ebbw Vale."[10]

Government

The 1945 General Election proved to be a landslide victory for the Labour Party, giving it a large enough majority to allow the implementation of the party's manifesto commitments and to introduce a program of far-reaching social reforms that were collectively dubbed the "Welfare State." The new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, appointed Aneurin Bevan as Minister of Health, with a remit that also covered Housing. Thus, the responsibility for instituting a new and comprehensive National Health Service, as well as tackling the country's severe post-war housing shortage, fell to the youngest member of Attlee's Cabinet in his first ministerial position. The free health service was paid for directly through government income, with no fees paid at the point of delivery. Government income was increased for the Welfare state expenditure by a severe increase in marginal tax rates for wealthy business owners in particular, as part of what the Labour government largely saw as the redistribution of the wealth created by the working class from the owners of large-scale industry to the workers. (Bevan argued that the percentage of tax from personal incomes rose from 9 percent in 1938 to 15 percent in 1949. But the lowest paid a tax rate of 1 percent, up from 0.2 percent in 1938, the middle income brackets paid 14 percent to 26 percent, up from 10 percent to 18 percent in 1938, the higher earners paid 42 percent, up from 29 percent, and the top earners 77 percent, up from 58 percent in 1938.)

The collective principle asserts that⌠no society can legitimately call itself civilized if a sick person is denied medical aid because of lack of means.[11]

On the "appointed day," July 5 1948, having overcome political opposition from both the Conservative Party and from within his own party, and after a dramatic showdown with the British Medical Association, which had threatened to derail the National Health Service scheme before it had even begun, as medical practitioners continued to withhold their support just months before the launch of the service, Bevan's National Health Service Act of 1946 came into force. After 18 months of ongoing dispute between the Ministry of Health and the BMA, Bevan finally managed to win over the support of the vast majority of the medical profession by offering a couple of minor concessions, but without compromising on the fundamental principles of his NHS proposals. Bevan later gave the famous quote that, in order to broker the deal, he had "stuffed their mouths with gold." Some 2,688 voluntary and municipal hospitals in England and Wales were nationalized and came under Bevan's supervisory control as Health Minister.

Bevan said:

The National Health service and the Welfare State have come to be used as interchangeable terms, and in the mouths of some people as terms of reproach. Why this is so it is not difficult to understand, if you view everything from the angle of a strictly individualistic competitive society. A free health service is pure Socialism and as such it is opposed to the hedonism of capitalist society.[12]

Substantial bombing damage and the continued existence of pre-war slums in many parts of the country made the task of housing reform particularly challenging for Bevan. Indeed, these factors, exacerbated by post-war restrictions on the availability of building materials and skilled labor, collectively served to limit Bevan's achievements in this area. 1946 saw the completion of 55,600 new homes; this rose to 139,600 in 1947, and 227,600 in 1948. While this was not an insignificant achievement, Bevan's rate of house building was seen as less of an achievement than that of his Conservative (indirect) successor, Harold Macmillan, who was able to complete some 300,000 a year as Minister for Housing in the 1950s. Macmillan was able to concentrate full-time on Housing, instead of being obliged, like Bevan, to combine his housing portfolio with that for Health (which for Bevan took the higher priority). However, critics said that the cheaper housing built by Macmillan was exactly the poor standard of housing that Bevan was aiming to replace. Macmillan's policies led to the building of cheap, mass-production, high-rise tower blocks, which have been heavily criticized since.

Bevan was appointed Minister of Labour in 1951, but soon resigned in protest at Hugh Gaitskell's introduction of prescription charges for dental care and spectaclesâcreated in order to meet the financial demands imposed by the Korean War. Appointment to the Labour Ministry was widely regarded as a demotion, or a sideways move. Having "carried out the tasks set him with distinction, it was not unreasonable for Bevan to expect promotion to one of the key cabinet posts, either the foreign secretary, or chancellor of the exchequer."[1]

Two other Ministers, John Freeman and Harold Wilson resigned at the same time.[13]

In 1952, Bevan published In Place of Fear, "the most widely read socialist book" of the period, according to a highly critical right-wing Labour MP Anthony Crosland.[14] Bevan begins: "A young miner in a South Wales colliery, my concern was with the one practical question: Where does power lie in this particular state of Great Britain, and how can it be attained by the workers?" In 1954, Gaitskell beat Bevan in a hard fought contest to be the Treasurer of the Labour Party.

Opposition

Out of the Cabinet, Bevan soon initiated a split within the Labour Party between the right and the left. For the next five years Bevan was the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party, who became known as Bevanites. They criticized high defense expenditure (especially for nuclear weapons) and opposed the more reformist stance of Clement Attlee. When the first British hydrogen bomb was exploded in 1955, Bevan led a revolt of 57 Labour MPs and abstained on a key vote. The Parliamentary Labour Party voted 141 to 113 to withdraw the whip from him, but it was restored within a month due to his popularity.

After the 1955 general election, Attlee retired as leader. Bevan contested the leadership against both Morrison and Labour right-winger Hugh Gaitskell but it was Gaitskell who emerged victorious. Bevan's remark that "I know the right kind of political Leader for the Labour Party is a kind of desiccated calculating machine" was assumed to refer to Gaitskell, although Bevan denied it (commenting upon Gaitskell's record as Chancellor of the Exchequer as having "proved" this). However, Gaitskell was prepared to make Bevan Shadow Colonial Secretary, and then Shadow Foreign Secretary in 1956. In this position, he was a vocal critic of the government's actions in the Suez Crisis, noticeably delivering high profile speeches in Trafalgar Square on November 4, 1956, at a protest rally, and devastating the government's actions and arguments in the House of Commons on December 5, 1956. That year, he was finally elected as party treasurer, beating George Brown.

Bevan dismayed many of his supporters when, speaking at the 1957 Labour Party conference, he decried unilateral nuclear disarmament, saying "It would send a British Foreign Secretary naked into the conference-chamber." This statement is often misconstrued. Bevan argued that unilateralism would result in Britain's loss of allies. One interpretation of Bevan's metaphor is that the nakedness comes from the lack of allies, not the lack of weapons.[15]

In 1959, despite suffering from terminal cancer, Bevan was elected as Deputy Leader of the Labour Party. He could do little in his new role and died the next year at the age of 62.

His last speech in the House of Commons, in which Bevan referred to the difficulties of persuading the electorate to support a policy which would make them less well-off in the short term but more prosperous in the long term, was quoted extensively in subsequent years.

Legacy

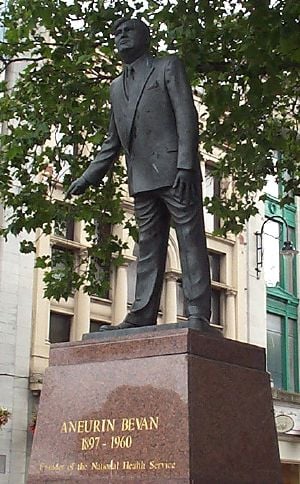

Bevan's enduring political legacy Britain's National Health Service, which many people consider to be one of the finest institutions ever developed within the public sector of the United Kingdom. On the negative side, he split the Labour Party and contributed to a long-lasting feud between those on the left and those on the right. Over the coming half-century, this helped to keep Labour out of power for much of the rest of the twentieth century.

In 2004, over 40 years after his death, he was voted first in a list of 100 Welsh Heroes, this being credited much to his contribution to the Welfare State after World War Two.[16]

Never embroiled in corruption or scandal, Bevan appears to have had a genuine desire to serve his nation. When people enjoyed economic security, they would work, he believed, to better others as well as themselves. "Emotional concern for individual life," he said, "is the most significant quality of a civilized human being" and can never be achieved if limited to any particular "colour, race, religion, nation or class."[17] His "religion" was "loving his fellow men and trying to serve them" and he could kneel with reverence in "chapel, synagogue or âŚmosque" in respect for a friend's faith although "he never pretended to be ⌠other than ... a humanist."[18] Socialism for him was committed to advancing the individual but always located individuals in society, thus it is always "compassionate and tolerant" and concerned with the "advancement of society as a whole." A genuinely democratic and socialist government never proscribes because political action is always "a choice between a number of possible alternatives"[19] Systems that exclude some from participation inevitably produce inequality and class friction, since, "social relationships become warped by self-interest".[20]

Publications

- 1944. Why Not Trust The Tories?. Published under the pseudonym, 'Celticus'. London, UK: V. Gollancz Ltd.

- 1952. In Place of Fear. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. 1990. London, UK: Quartet. ISBN 9780704301221.

- with Charles Webster. 1991. Aneurin Bevan on the National Health Service. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford, Welcome Unit for the History of Medicine. ISBN 9780906844090.

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 Aneurin BevanâLabour's lost leader BBC, July 1, 1998. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- â Clare Beckett and Francis Beckett, Bevan (London: Haus, 2004, ISBN 9781904341635), 129.

- â Beckett and Beckett, 4.

- â Aneurin Bevan People's Collection Wales. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- â Beckett and Beckett, 15.

- â Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds, NYE: The Political Life of Aneurin Bevan (I.B. Tauris, 2014, ISBN 978-1780762098).

- â John Campbell âSqualid Nuisanceâ? Nye Bevan's Finest Hour Finest Hour 172, June 12, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- â Karl Marx, Another British Revelation Marx Engels Public Archive. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- â David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 1945-1951 (Walker Books, 2008, ISBN 978-0802716934), 64.

- â Foreign News: Yalu Hullabaloo TIME, July 14, 1952. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- â Aneurin Bevan, In Place of Fear (Hassell Street Press, 2021 (original 1952), ISBN 1014234190), 100.

- â Bevan, 106.

- â Aneurin Bevan and the foundation of the NHS Socialist Health Association. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- â Anthony Crosland, The Future of Socialism (Constable & Robinson, 2006 (original 1957), ISBN 978-1845294854), 52.

- â John Callaghan, The Labour Party and Foreign Policy: A History (Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-0415246965).

- â 100 Welsh Heroes ewegottalove wales. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- â Beckett and Beckett, 95-96.

- â Beckett and Beckett, 129.

- â Beckett and Beckett, 130-131.

- â Beckett and Beckett, 132.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beckett, Clare, and Francis Beckett. Bevan. London: Haus, 2004. ISBN 9781904341635

- Callaghan, John. The Labour Party and Foreign Policy: A History. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0415246965

- Campbell, John. Aneurin Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism. New York: Norton, 1987. ISBN 0393024520

- Crosland, Anthony. The Future of Socialism. Constable & Robinson, 2006 (original 1957). ISBN 978-1845294854

- Foot, Michael. Aneurin Bevan, a Biography. New York: Atheneum, 1963. ISBN 9780689105876

- Goodman, Geoffrey. The State of the Nation: The Political Legacy of Aneurin Bevan. London: V. Gollancz, 1997. ISBN 9780575063082

- Kynaston, David. Austerity Britain, 1945-1951. Walker Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0802716934

- Laugharne, Peter J. (ed). Aneurin Bevan - A Parliamentary Odyssey: Volume I, Speeches at Westminster 1929-1944. Liverpool, UK: Manutius Press, 1996. ISBN 9781873534137

- Laugharne, Peter J (ed). Aneurin Bevan - A Parliamentary Odyssey: Volume II, Speeches at Westminster 1945-1960. Liverpool, UK: Manutius Press, 2000.

- Lee, Jennie. My Life with Nye. London: Cape, 1980. ISBN 9780224017855

- Rintala, Marvin. Creating the National Health Service: Aneurin Bevan and the Medical Lords. London: Frank Cass, 2003. ISBN 9780714655062

- Thomas-Symonds, Nicklaus. NYE: The Political Life of Aneurin Bevan. I.B. Tauris, 2014. ISBN 978-1780762098

External links

All links retrieved July 27, 2023.

- Aneurin Bevan and the foundation of the NHS.

- Aneurin Bevan (1897 - 1960) BBC

- Aneurin Bevan Society

- Aneurin Bevan (1897-1960) Humanist Heritage

- Bevan, Aneurin (1897 - 1960), politician and one of the founders of the Welfare State Dictionary of Welsh Biography

- Aneurin Bevan National Portrait Gallery

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Evan Davies |

Member of Parliament for Ebbw Vale 1929â1960 |

Succeeded by: Michael Foot |

| Media offices | ||

| Preceded by: Raymond Postgate |

Editor of Tribune (with Jon Kimche) 1941â1945 |

Succeeded by: Frederic Mullally. and Evelyn Anderson |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by: Henry Willink |

Minister of Health 1945â1951 |

Succeeded by: Hilary Marquand |

| Preceded by: George Isaacs |

Minister of Labour and National Service 1951 |

Succeeded by: Alfred Robens |

| Preceded by: Alfred Robens |

Shadow Foreign Secretary 1956â1959 |

Succeeded by: Denis Healey |

| Preceded by: Hugh Gaitskell |

Treasurer of the Labour Party 1956â1960 |

Succeeded by: Harry Nicholas |

| Preceded by: Jim Griffiths |

Deputy Leader of the British Labour Party 1959â1960 |

Succeeded by: George Brown |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.