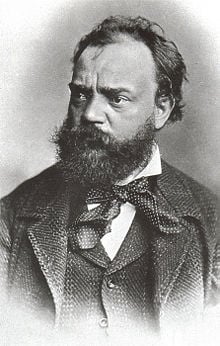

| Antonín Dvořák | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Antonín Leopold Dvořák |

| Born | September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, Prague, Austrian Empire |

| Died | May 1, 1904, Prague, Czechoslovakia |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, organist |

| Notable instrument(s) | |

| Orchestra Composer Organ | |

Antonín Leopold Dvořák (September 8, 1841 – May 1, 1904) was a nineteenth century Czech composer whose works include operas, oratorios, symphonies, chamber music, and concertos. Dvořák's music notably combines the Viennese classical tradition with the folk idioms and melodies of his native Bohemia.

Widely regarded as the most distinguished of Czech composers, Dvorák wove charming, memorable melodies into his symphonic and chamber music. Among his most widely recognized and performed works, the Symphony No. 9 ("From the New World," 1893) and Cello Concerto (1894-1895) are cornerstones of the orchestral repertory.

Dvořák's Stabat Mater has been called "one of the most beautiful and most moving pieces of music ever to come out of the Czech lands [and] … one of the most powerful declarations of faith in the history of music."[1] Begun in 1875, the work is an expression of reconciliation by faith of the shattering loss of the composer's two small children.

A person of humble origins and demeanor and of deep faith, Dvořák often attributed his musical talents as being "a gift from God." Upon the completion of one of his settings of the Catholic Mass, he proclaimed, "Do not wonder that I am so religious. An artist who is not could not produce anything like this."

Biography

Early life and career

Dvořák was born on September 8, 1841, in Nelahozeves, near Prague (then the Austrian Empire, today the Czech Republic), where he spent most of his life. His father was a butcher, innkeeper, and professional player of the zither. Dvořák's parents recognized his musical talent early, and he received his earliest musical education at the village school, which he entered in 1847. He studied music in Prague's only Organ School at the end of the 1850s, and gradually developed into an accomplished violinist and violist. Throughout the 1860s, he played viola in the Bohemian Provisional Theater Orchestra, which from 1866, was conducted by Bedřich Smetana. The need to supplement his income by teaching left Dvořák with limited free time, and in 1871, he gave up playing in the orchestra in order to compose. During this time, Dvořák fell in love with one of his pupils and wrote a song cycle, Cypress Trees, that expressed his anguish at her marriage to another man. In 1873, he married this pupil's sister, Anna Cermakova.

At about this time, Dvořák began to be recognized as a significant composer. He became the organist at St. Adalbert's Church, Prague, and began a period of prolific composition. Dvořák composed his String Quintet No. 2 in 1875, and in 1877, the critic Eduard Hanslick informed him that his music had attracted the attention of Johannes Brahms. Brahms contacted the musical publisher Simrock, who as a result, commissioned Dvořák's Slavonic Dances. Published in 1878, these were an immediate success. Dvořák's Stabat Mater (1880) was performed abroad, and after a successful performance in London in 1883, Dvořák was invited to visit England, where he appeared to great acclaim in 1884. His Symphony No. 7 was commissioned in London and it premiered there in 1885. In 1891, Dvořák received an honorary degree from Cambridge University, and his Requiem Mass premiered later that year in Birmingham.

America (1892–1895)

From 1892 to 1895, Dvořák was the director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York City, which had been founded by a wealthy and philanthropic socialite, Jeannette Thurber. The school was demolished in 1911 and replaced by what is now a high school, but it was located at 126-128 17th Street in Manhattan, at the southeast corner of the intersection with Irving Place, a block east of Union Square.[2] Here Dvořák met with Harry Burleigh, one of the earliest African-American composers. Although Burleigh was never his pupil, he introduced traditional American spiritual music to Dvořák at the latter's request.

In the winter and spring of 1893 while in New York, Dvořák wrote his most popular work, the Symphony No. 9 known as From the New World. He spent the summer of 1893 with his family in the Czech-speaking community of Spillville, Iowa. While there, he composed two of his most famous chamber works, the String Quartet No. 12 in F (the American) and the String Quintet in E flat.

Over the course of three months in 1895, Dvořák wrote his Cello Concerto in B minor, which was to become one of his most popular works. Yet, problems with Mrs. Thurber about his salary, together with increasing recognition in Europe (he had been made an honorary member of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna) made him decide to return home.

Later career

During his final years, Dvořák's compositional work centered on opera and chamber music. In 1896, he visited London for the last time to hear the premiere of his Cello concerto. In 1897, his daughter married his pupil, the composer Josef Suk. Dvořák was director of the Conservatory in Prague from 1901 until his death in 1904. He is interred in the Vyšehrad cemetery in Prague. He left an unfinished work, the Cello Concerto in A Major (1865), which was completed and orchestrated by the German composer Günter Raphael between 1925 and 1929 and by Jarmil Burghauser in 1952.

Works

Dvořák wrote in a variety of forms: His nine symphonies generally adhere to classical models that Beethoven would have recognized, but he also worked in the newly developed symphonic poem form, and the influence of Richard Wagner is apparent in some works. Many of his works display the influence of Czech folk music, both in terms of rhythms and melodic characteristics. Perhaps the best known examples are the two sets of Slavonic Dances. Dvořák also wrote operas (the best known of which is Rusalka) chamber music (including a number of string quartets, and quintets), songs, choral music, and piano music.

Dvořák's works were cataloged by Jarmil Burghauser in Antonín Dvořák. Thematic Catalogue. Bibliography. Survey of Life and Work (Export Artia Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1960). In this catalogue, for example, the New World Symphony (Opus 95) is B178.

Symphonies

During Dvořák’s life, only 5 symphonies were widely known. The first published was the 6th, dedicated to the conductor Hans Richter. After Dvořák’s death, research uncovered four unpublished symphonies, of which the manuscript of the first had even been lost to the composer himself. This led to an unclear situation in which the Symphony No. 9 New World symphony has alternately been called the 5th, 8th, and 9th. This article uses the modern numbering system, according to the order in which they were written.

Dvořák wrote his Symphony No. 1 in C minor when he was only 24 years old. Later subtitled The Bells of Zlonice after a village in Dvořák's native Bohemia, it is clearly the work of an inexperienced composer. Yet it remains a fascinating study of form, orchestration, and harmony. The scherzo is considered to be the strongest movement. It has many formal similarities with Beethoven's 5th Symphony (for example, the movements follow the same keys: C minor, A flat major, C minor, C major); however, in harmony and instrumentation, Dvořák's First follows the style of Franz Schubert.

Symphony No. 2 in B flat major still uses Beethoven as a model. But Symphony No. 3 in E flat major clearly shows the sudden and profound impact of Dvořák's recent acquaintance with the music of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt. The influence of Wagner was not lasting; it is greatly reduced in Symphony No. 4 in D minor. Again the scherzo is the highlight, but Dvořák shows his absolute mastery of all formal aspects.

Dvořák's Symphony No. 5 in F major and Symphony No. 6 in D major are largely pastoral in nature. The Fifth has a dark slow movement which quotes the first four notes of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1 for its main theme. The Sixth shows a very strong resemblance to the Symphony No. 2 of Brahms, particularly in the outer movements.

Symphony No. 7 in D minor of 1885 is perhaps the most romantic symphony by the composer and exhibits greater formal tautness and dramatic intensity than the more famous Symphony No. 9. The 7th could hardly be a starker contrast to bucolic Symphony No. 8 in G major, a work which Karl Schumann compares to the works of Gustav Mahler.

By far the most popular, however, is Dvořák's Symphony No. 9 in E minor, better known under its subtitle, From the New World. This was written between January and May 1893, while he was in New York. At the time of its composition, Dvořák claimed that he used elements from American music such as spirituals and Native American music in this work, but he later denied this. The first movement has a solo flute passage very reminiscent of Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, and one of his students later reported that the second movement depicted, programatically, the sobbing of Hiawatha. The second movement was so reminiscent of a Black spiritual that William Arms Fisher wrote lyrics for it and called it Goin' Home. Dvořák was interested in indigenous American music, but in an article published in the New York Herald on December 15, 1893, he wrote "[In the 9th symphony] I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of the Indian music." It is generally accepted that the work has more in common with the folk music of Dvořák's native Bohemia than with American music.

Concerti

As the music critic Harold Schonberg put it, Dvořák wrote "an attractive Piano Concerto in G minor with a rather ineffective piano part, a beautiful Violin Concerto in A minor, and a supreme Cello Concerto in B minor" (The Lives of the Great Composers, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, revised edition, 1980). The Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in G minor, Op. 33 was the first of three concertos that Dvořák composed and orchestrated and it is perhaps the least known of those three. Dvořák composed his piano concerto from late August through September 14, 1876. Its autograph version contains many corrections, erasures, cuts and additions. The bulk of these changes were made in the piano part. The work was premiered in Prague on March 24, 1878, with the orchestra of the Prague Provisional Theatre conducted by Adolf Cech with the Czech pianist Karel Slavkovsky as soloist. As Dvořák wrote: "I see I am unable to write a Concerto for a virtuoso; I must think of other things." Instead, what Dvořák thought of and created was a concerto with remarkable symphonic values in which the piano plays a leading part in the orchestra rather than opposed to it. The Czech pianist Vilém Kurz subsequently wrote an alternative, somewhat more virtuosic piano part for the concerto which may be either played partially or entirely in lieu of Dvořák's part according to the performer's preference.

The Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 53 was the second of the three concertos that Dvořák composed and orchestrated. He had met the great violinist Joseph Joachim in 1878 and decided to write a concerto for him. He finished it in 1879, but Joachim was skeptical of the work. He was a strict classicist and objected to Dvořák's inter alia or his abrupt truncation of the first movement's orchestral tutti. He also did not like the fact that the recapitulation was similarly cut short and that it led directly to the slow movement. He never actually played the piece. The concerto was premiered in 1883 by the violinist František Ondříček in Prague who subsequently performed it in its debuts in Vienna and London.

The concerto is in the classical three movements. The second (slow) movement is especially celebrated for its lyricism.

The Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in B minor, Op. 104 was the last composed of Dvořák's concertos and is considered to be one of the greatest works in that genre of the late nineteenth century. He wrote it in 1894-1895 for his friend, the cellist Hanuš Wihan. Wihan and others had asked for a cello concerto for some time, but Dvořák always refused, stating that the cello was a fine orchestral instrument but totally insufficient for a solo concerto.

Dvořák composed the concerto in New York while serving as the Director of the National Conservatory. In 1894, Victor Herbert, who was also teaching at the Conservatory, had written a cello concerto and presented it in a series of concerts. Dvořák attended at least two performances of Victor Herbert's cello concerto and was inspired to fulfill Wihan's request for a cello concerto. Dvořák's concerto received its premiere in London on March 16, 1896, with the English cellist Leo Stern. The work was well received. Brahms said of the work, "Had I known that one could write a cello concerto like this, I would have written one long ago!"

In 1865, Dvořák had composed an earlier Cello Concerto in A Major, B.10 (the surviving score of which is for cello and piano). It was orchestrated by his cataloger, Burghauser, and published in this form in 1952.

Operas and tone poems

Dvořák’s critical acclaim as a composer of symphonies and concertos gave him a strong desire to write for the opera. Of all his operas, only Rusalka and, to a much lesser extent, Kate and the Devil, are played on contemporary opera stages with any frequency outside the Czech Republic. This is due partly to their uneven invention, partly to their inadequate libretti, and perhaps also partly due to their staging requirements. For example, The Jacobin, Armida, Wanda, and Dimitrij need stages large enough to portray invading armies.

The German-born conductor Gerd Albrecht has conducted many of Dvořák’s operas on the Orfeo and Supraphon labels. Only Dvořák’s opera, King Alfred, is presently unavailable.

Like his contemporaries Jean Sibelius, Franz Liszt, and Richard Strauss, the symphonic poem became an important vehicle for Dvorak's creative energies. Dvorak, like Sibelius, looked to native folk myths and legends for source materials and based several of these large-scale compositions on the epic poems of his countryman, poet Karel Jaromir Erben.

Legacy

Antonin Dvorak's music is deeply infused with the spirit of his native Czech homeland and as such remains a source of great national pride. Like other "nationalist" composers, Dvorak fused musical folk elements into formal compositional framework in masterful ways. Whether in his absolute music (symphonies, concerti, chamber music) or in his programmatic works (tone poems and operas) the melodic and rhythmic characteristics of Czech folk music is highly evident.

Dvorak's love of country is further evident in his symphonic poems, which are often based on Czech mythology and folk legends. His four great symphonic poems of 1896, "The Golden Spinning Wheel," "The Wood Dove," "The Noonday Witch," and "The Water Goblin," are based on the epic poems of his countryman, poet Karel Jaromir Erben. To this day these works instill a great sense of national pride into the musical sphere of Czech culture.

His faith played an important role in his work, as when he expressed upon completing the second movement of his dramatic Seventh Symphony, "Today I have completed the second movement, Andante, of my new symphony, and I am so happy and contented in my work as I have always been, and God grant, may always be, for my slogan is and always shall be; God, Love and Country! And that alone can lead to a happy goal."

Dvořák's home in Manhattan was demolished to make room for a Beth Israel Medical Center, despite protests of Czech nationalists, especially Václav Havel, who wanted the house preserved as a historical site. To honor Dvořák, a statue of him was erected in Stuyvesant Square. Interestingly, Neil Armstrong took a recording of the New World symphony to the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission, the first Moon landing, in 1969.

Notes

- ↑ Radio.cz, Music for Easter: Dvořák's Stabat Mater. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ↑ Jim Naureckas, New York Songlines-Seventeenth Street. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beckerman, Michael Brim. Dvorak and his World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-691-03386-2.

- Clapham, John. Dvorak. 1979. ISBN 0-715-37790-6.

- Dunnett, Roderic. Antonin Dvorak. Watford, Herts, UK: Exley, 1995. ISBN 1-850-15486-4.

- Fischl, Viktor. Antonin Dvorak, his Achievement. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1970. ISBN 0-837-13922-8.

- Tibbetts, John C. Dvorak in America, 1892-1895. Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1993. ISBN 0-931-34056-X.

External links

All links retrieved October 30, 2021.

- "Home page of the Dvořák Society", Dvořák Society for Czech and Slovak Music.

- Christopher Lydon, September 13, 2005; "Dvořák to Duke Ellington", ''Radio Open Source.

- "Home Page", The Antonín Dvořák Memorial at Vysoká u Příbrami.

- "Püblic Domain Sheet Music by Dvorak", IMSLP.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.