Apollo 11

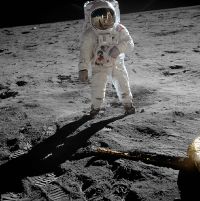

Buzz Aldrin on the Moon as photographed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Left to right: Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Apollo 11 was the spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin formed the American crew that landed the Apollo Lunar Module Eagle on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC. Armstrong became the first person to step onto the lunar surface six hours and 39 minutes later on July 21 at 02:56 UTC; Aldrin joined him 19 minutes later. They spent about two and a quarter hours together outside the spacecraft, and they collected 47.5 pounds (21.5 kg) of lunar material to bring back to Earth. Command module pilot Michael Collins flew the Command Module Columbia alone in lunar orbit while they were on the Moon's surface. Armstrong and Aldrin spent 21 hours, 36 minutes on the lunar surface at a site they named Tranquility Base before lifting off to rejoin Columbia in lunar orbit.

Apollo 11 was launched by a Saturn V rocket from Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, Florida, on July 16 at 13:32 UTC, and it was the fifth crewed mission of NASA's Apollo program. The Apollo spacecraft had three parts: a command module (CM) with a cabin for the three astronauts, the only part that returned to Earth; a service module (SM), which supported the command module with propulsion, electrical power, oxygen, and water; and a lunar module (LM) that had two stages—a descent stage for landing on the Moon and an ascent stage to place the astronauts back into lunar orbit.

After being sent to the Moon by the Saturn V's third stage, the astronauts separated the spacecraft from it and traveled for three days until they entered lunar orbit. Armstrong and Aldrin then moved into Eagle and landed in the Sea of Tranquility on July 20. The astronauts used Eagle's ascent stage to lift off from the lunar surface and rejoin Collins in the command module. They jettisoned Eagle before they performed the maneuvers that propelled Columbia out of the last of its 30 lunar orbits onto a trajectory back to Earth.[4] They returned to Earth and splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24 after more than eight days in space.

Armstrong's first step onto the lunar surface was broadcast on live TV to a worldwide audience. He described the event as "one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind." Eric Jones of the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal explains that the "a" article was intended, whether or not it was said; the intention was to contrast a man (an individual's action) and mankind (as a species).[5] Apollo 11 effectively ended the Space Race and fulfilled a national goal proposed in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy: "before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth." The moon landing was not only a point of pride for the United States, but for humankind. An estimated 600 million people watch the moon landing live on TV all around the world - over three times the entire population of the United States in 1969.

Historical Background

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the United States was engaged in the Cold War, a geopolitical rivalry with the Soviet Union.[6] On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. This surprise success fired fears and imaginations around the world. It demonstrated that the Soviet Union had the capability to deliver nuclear weapons over intercontinental distances, and challenged American claims of military, economic and technological superiority.[7] This precipitated the Sputnik crisis, and triggered the Space Race.[8] President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded to the Sputnik challenge by creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and initiating Project Mercury,[9] which aimed to launch a man into Earth orbit.[10] But on April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space, and the first to orbit the Earth. Nearly a month later, on May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American in space, completing a 15-minute suborbital journey. After being recovered from the Atlantic Ocean, he received a congratulatory telephone call from Eisenhower's successor, John F. Kennedy.[11]

Since the Soviet Union had higher lift capacity launch vehicles, Kennedy chose, from among options presented by NASA, a challenge beyond the capacity of the existing generation of rocketry, so that the US and Soviet Union would be starting from a position of equality. A crewed mission to the Moon would serve this purpose.[12]

On May 25, 1961, Kennedy addressed the United States Congress on "Urgent National Needs" and declared:

I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade [1960s] is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish. We propose to accelerate the development of the appropriate lunar space craft. We propose to develop alternate liquid and solid fuel boosters, much larger than any now being developed, until certain which is superior. We propose additional funds for other engine development and for unmanned explorations—explorations which are particularly important for one purpose which this nation will never overlook: the survival of the man who first makes this daring flight. But in a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the Moon—if we make this judgment affirmatively, it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.[13]

On September 12, 1962, Kennedy delivered another speech before a crowd of about 40,000 people in the Rice University football stadium in Houston, Texas.[14] A widely quoted refrain from the middle portion of the speech reads as follows:

There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again. But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas? We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the Moon ... We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.[15]

In spite of that, the proposed program faced the opposition of many Americans and was dubbed a "moondoggle" by Norbert Wiener, a mathematician at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[16] The effort to land a man on the Moon already had a name: Project Apollo.[17] When Kennedy met with Nikita Khrushchev, the Premier of the Soviet Union in June 1961, he proposed making the Moon landing a joint project, but Khrushchev did not take up the offer.[18] Kennedy again proposed a joint expedition to the Moon in a speech to the United Nations General Assembly on September 20, 1963.[19] The idea of a joint Moon mission was abandoned after Kennedy's death.

Technical Challenges

An early and crucial decision was choosing lunar orbit rendezvous over both direct ascent and Earth orbit rendezvous. A space rendezvous is an orbital maneuver in which two spacecraft navigate through space and meet up. In July 1962 NASA head James Webb announced that lunar orbit rendezvous would be used[20] and that the Apollo spacecraft would have three major parts: a command module (CM) with a cabin for the three astronauts, and the only part that returned to Earth; a service module (SM), which supported the command module with propulsion, electrical power, oxygen, and water; and a lunar module (LM) that had two stages—a descent stage for landing on the Moon, and an ascent stage to place the astronauts back into lunar orbit.[21] This design meant the spacecraft could be launched by a single Saturn V rocket that was then under development.[22]

Technologies and techniques required for Apollo were developed by Project Gemini.[23] The Apollo project was enabled by NASA's adoption of new advances in semiconductor electronic technology, including metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) in the Interplanetary Monitoring Platform (IMP)[24] and silicon integrated circuit (IC) chips in the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC).[25]

Apollo Program

Project Apollo was abruptly halted in its early phase by the Apollo 1 fire on January 27, 1967 in which astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger B. Chaffee died. After the subsequent investigation, the program restarted.[26] In October 1968, Apollo 7 evaluated the command module in Earth orbit,[27] and in December Apollo 8 tested it in lunar orbit.[28] In March 1969, Apollo 9 put the lunar module through its paces in Earth orbit,[29] and in May Apollo 10 conducted a "dress rehearsal" in lunar orbit. By July 1969, all was in readiness for Apollo 11 to take the final step onto the Moon.[30]

The Soviet Union competed with the US in the Space Race, but its early lead was lost through repeated failures in development of the N1 launcher, which was comparable to the Saturn V.[31] The Soviets tried to beat the US to return lunar material to the Earth by means of uncrewed probes. On July 13, three days before Apollo 11's launch, the Soviet Union launched Luna 15, which reached lunar orbit before Apollo 11. During descent, a malfunction caused Luna 15 to crash in Mare Crisium about two hours before Armstrong and Aldrin took off from the Moon's surface to begin their voyage home. The Nuffield Radio Astronomy Laboratories radio telescope in England recorded transmissions from Luna 15 during its descent, and these were released in July 2009 for the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11.[32]

Personnel

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Neil A. Armstrong Second and last spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot | Michael Collins Second and last spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Edwin "Buzz" E. Aldrin Jr. Second and last spaceflight | |

The initial crew assignment of Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Jim Lovell, and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Buzz Aldrin on the backup crew for Apollo 9 was officially announced on November 20, 1967.[33] Lovell and Aldrin had previously flown together as the crew of Gemini 12. Due to design and manufacturing delays in the LM, Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 swapped primary and backup crews, and Armstrong's crew became the backup for Apollo 8. Based on the normal crew rotation scheme, Armstrong was then expected to command Apollo 11.[34]

There would be one change. Michael Collins, the CMP on the Apollo 8 crew, began experiencing trouble with his legs. Doctors diagnosed the problem as a bony growth between his fifth and sixth vertebrae, requiring surgery.[35] Lovell took his place on the Apollo 8 crew, and when Collins recovered he joined Armstrong's crew as CMP. In the meantime, Fred Haise filled in as backup LMP, and Aldrin as backup CMP for Apollo 8.[36] Apollo 11 was the second American mission where all the crew members had prior spaceflight experience. The Apollo 10 crew also had prior experience. The next was not until STS-26 in 1988.[4]

Deke Slayton gave Armstrong the option to replace Aldrin with Lovell, since some thought working with Aldrin was difficult. Armstrong had no issues working with Aldrin, but thought it over for a day before declining. He thought Lovell deserved to command his own mission (eventually Apollo 13).[37]

The Apollo 11 primary crew had none of the close cheerful camaraderie characterized by that of Apollo 12. Instead they forged an amiable working relationship. Armstrong in particular was notoriously aloof, but Collins, who considered himself a loner, confessed to rebuffing Aldrin's attempts to create a more personal relationship.[38] Aldrin and Collins described the crew as "amiable strangers."[39] Armstrong did not agree with the assessment, saying "all the crews I was on worked very well together."[40]

Preparations

Site selection

NASA's Apollo Site Selection Board announced five potential landing sites on February 8, 1968. These were the result of two years' worth of studies based on high-resolution photography of the lunar surface by the five uncrewed probes of the Lunar Orbiter program and information about surface conditions provided by the Surveyor program.[41] The best Earth-bound telescopes could not resolve features with the resolution Project Apollo required.[42] The landing site had to be close to the lunar equator to minimize the amount of propellant required, clear of obstacles to minimize maneuvering, and flat to simplify the task of the landing radar. Scientific value was not a consideration.[43]

Areas that appeared promising on photographs taken on Earth were often found to be totally unacceptable. The original requirement that the site be free of craters had to be relaxed, as no such site was found.[42] Five sites were considered: Sites 1 and 2 were in the Sea of Tranquility (Mare Tranquilitatis); Site 3 was in the Central Bay (Sinus Medii); and Sites 4 and 5 were in the Ocean of Storms (Oceanus Procellarum).[41] The final site selection was based on seven criteria:

- The site needed to be smooth, with relatively few craters;

- with approach paths free of large hills, tall cliffs or deep craters that might confuse the landing radar and cause it to issue incorrect readings;

- reachable with a minimum amount of propellant;

- allowing for delays in the launch countdown;

- providing the Apollo spacecraft with a free-return trajectory, one that would allow it to coast around the Moon and safely return to Earth without requiring any engine firings should a problem arise on the way to the Moon;

- with good visibility during the landing approach, meaning the Sun would be between 7 and 20 degrees behind the LM; and

- a general slope of less than two degrees in the landing area.

The requirement for the Sun angle was particularly restrictive, limiting the launch date to one day per month.[41] A landing just after dawn was chosen to limit the temperature extremes the astronauts would experience.[44] The Apollo Site Selection Board selected Site 2, with Sites 3 and 5 as backups in the event that the launch had to be delayed. In May 1969, Apollo 10's lunar module flew to within 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) of Site 2, and reported it was acceptable.[45]

First-step decision

During the first press conference after the Apollo 11 crew was announced, the first question was, "Which one of you gentlemen will be the first man to step onto the lunar surface?"[46] Slayton told the reporter it had not been decided, and Armstrong added that it was "not based on individual desire."[47]

One of the first versions of the egress checklist had the lunar module pilot exit the spacecraft before the command module pilot, which matched what had been done in previous missions.[48] The commander had never performed the spacewalk.[49] Reporters wrote in early 1969 that Aldrin would be the first man to walk on the Moon, and Associate Administrator George Mueller told reporters he would be first as well. Aldrin heard that Armstrong would be the first because Armstrong was a civilian, which made Aldrin livid. Aldrin attempted to persuade other lunar module pilots he should be first, but they responded cynically about what they perceived as a lobbying campaign. Attempting to stem interdepartmental conflict, Slayton told Aldrin that Armstrong would be first since he was the commander. The decision was announced in a press conference on April 14, 1969.[50]

For decades, Aldrin believed the final decision was largely driven by the lunar module's hatch location. Because the astronauts had their spacesuits on and the spacecraft was so small, maneuvering to exit the spacecraft was difficult. The crew tried a simulation in which Aldrin left the spacecraft first, but he damaged the simulator while attempting to egress. While this was enough for mission planners to make their decision, Aldrin and Armstrong were left in the dark on the decision until late spring.[51] Slayton told Armstrong the plan was to have him leave the spacecraft first, if he agreed. Armstrong said, "Yes, that's the way to do it."[52]

The media accused Armstrong of exercising his commander's prerogative to exit the spacecraft first.[53] Chris Kraft revealed in his 2001 autobiography that a meeting occurred between Gilruth, Slayton, Low, and himself to make sure Aldrin would not be the first to walk on the Moon. They argued that the first person to walk on the Moon should be like Charles Lindbergh, a calm and quiet person. They made the decision to change the flight plan so the commander was the first to egress from the spacecraft.[54]

Pre-launch

The ascent stage of lunar module LM-5 arrived at the Kennedy Space Center on January 8, 1969, followed by the descent stage four days later, and Command and Service Module CM-107 on January 23.[1] There were several differences between LM-5 and Apollo 10's LM-4; LM-5 had a VHF radio antenna to facilitate communication with the astronauts during their EVA on the lunar surface; a lighter ascent engine; more thermal protection on the landing gear; and a package of scientific experiments known as the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package (EASEP). The only change in the configuration of the command module was the removal of some insulation from the forward hatch.[55] The command and service modules were mated on January 29, and moved from the Operations and Checkout Building to the Vehicle Assembly Building on April 14.[1]

The S-IVB third stage of Saturn V AS-506 had arrived on January 18, followed by the S-II second stage on February 6, S-IC first stage on February 20, and the Saturn V Instrument Unit on February 27. At 1230 on May 20, the 5,443-tonne (Template:Convert/multi2LoffAonSon) assembly departed the Vehicle Assembly Building atop the crawler-transporter, bound for Launch Pad 39A, part of Launch Complex 39, while Apollo 10 was still on its way to the Moon. A countdown test commenced on June 26, and concluded on July 2. The launch complex was floodlit on the night of July 15, when the crawler-transporter carried the mobile service structure back to its parking area.[1] In the early hours of the morning, the fuel tanks of the S-II and S-IVB stages were filled with liquid hydrogen. Fueling was completed by three hours before launch.[56] Launch operations were partly automated, with 43 programs written in the ATOLL programming language.[57]

Slayton roused the crew shortly after 0400, and they showered, shaved, and had the traditional pre-flight breakfast of steak and eggs with Slayton and the backup crew. They then donned their space suits and began breathing pure oxygen. At 0630, they headed out to Launch Complex 39.[58] Haise entered Columbia about three hours and ten minutes before launch time. Along with a technician, he helped Armstrong into the left hand couch at 06:54. Five minutes later, Collins joined him, taking up his position on the right hand couch. Finally, Aldrin entered, taking the center couch.[56] Haise left around two hours and ten minutes before launch.[59] The closeout crew sealed the hatch, and the cabin was purged and pressurized. The closeout crew then left the launch complex about an hour before launch time. The countdown became automated at three minutes and twenty seconds before launch time. Over 450 personnel were at the consoles in the firing room.[56]

Mission

Launch and flight to lunar orbit

An estimated one million spectators watched the launch of Apollo 11 from the highways and beaches in the vicinity of the launch site. Dignitaries included the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General William Westmoreland, four cabinet members, 19 state governors, 40 mayors, 60 ambassadors and 200 congressmen. Vice President Spiro Agnew viewed the launch with the former president, Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife Lady Bird Johnson.[56] Around 3,500 media representatives were present.[60] About two-thirds were from the United States; the rest came from 55 other countries. The launch was televised live in 33 countries, with an estimated 25 million viewers in the United States alone. Millions more around the world listened to radio broadcasts.[56] President Richard Nixon viewed the launch from his office in the White House with his NASA liaison officer, Apollo astronaut Frank Borman.[61]

Saturn V AS-506 launched Apollo 11 on July 16, 1969, at 13:32:00 UTC (9:32:00 EDT).[1] At 13.2 seconds into the flight, the launch vehicle began to roll into its flight azimuth of 72.058°. Full shutdown of the first-stage engines occurred about 2 minutes and 42 seconds into the mission, followed by separation of the S-IC and ignition of the S-II engines. The second stage engines then cut off and separated at about 9 minutes and 8 seconds, allowing the first ignition of the S-IVB engine a few seconds later.[4]

Apollo 11 entered Earth orbit at an altitude of 100.4 nautical miles (185.9 km) by 98.9 nautical miles (183.2 km), twelve minutes into its flight. After one and a half orbits, a second ignition of the S-IVB engine pushed the spacecraft onto its trajectory toward the Moon with the trans-lunar injection (TLI) burn at 16:22:13 UTC. About 30 minutes later, with Collins in the left seat and at the controls, the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver was performed. This involved separating Columbia from the spent S-IVB stage, turning around, and docking with Eagle still attached to the stage. After the LM was extracted, the combined spacecraft headed for the Moon, while the rocket stage flew on a trajectory past the Moon.[4] This was done to avoid the third stage colliding with the spacecraft, the Earth, or the Moon. A slingshot effect from passing around the Moon threw it into an orbit around the Sun.[62]

On July 19 at 17:21:50 UTC, Apollo 11 passed behind the Moon and fired its service propulsion engine to enter lunar orbit.[63] In the thirty orbits that followed, the crew saw passing views of their landing site in the southern Sea of Tranquility about 12 miles (19 km) southwest of the crater Sabine D. The site was selected in part because it had been characterized as relatively flat and smooth by the automated Ranger 8 and Surveyor 5 landers and the Lunar Orbiter mapping spacecraft and unlikely to present major landing or EVA challenges.[64] It lay about 25 kilometers (16 mi) southeast of the Surveyor 5 landing site, and 68 kilometers (42 mi) southwest of Ranger 8's crash site.[65]

Lunar descent

At 12:52:00 UTC on July 20, Aldrin and Armstrong entered Eagle, and began the final preparations for lunar descent.At 17:44:00 Eagle separated from Columbia. Collins, alone aboard Columbia, inspected Eagle as it pirouetted before him to ensure the craft was not damaged, and that the landing gear was correctly deployed.[65] Armstrong exclaimed: "The Eagle has wings!" [66]

As the descent began, Armstrong and Aldrin found themselves passing landmarks on the surface two or three seconds early, and reported that they were "long"; they would land miles west of their target point. Eagle was traveling too fast. The problem could have been mascons—concentrations of high mass that could have altered the trajectory. Flight Director Gene Kranz speculated that it could have resulted from extra air pressure in the docking tunnel. Or it could have been the result of Eagle's pirouette maneuver.[67]

Five minutes into the descent burn, and 6,000 feet (1,800 m) above the surface of the Moon, the LM guidance computer (LGC) distracted the crew with the first of several unexpected 1201 and 1202 program alarms. Inside Mission Control Center, computer engineer Jack Garman told Guidance Officer Steve Bales it was safe to continue the descent, and this was relayed to the crew. The program alarms indicated "executive overflows," meaning the guidance computer could not complete all its tasks in real time and had to postpone some of them.[68] Margaret Hamilton, the Director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming at the MIT Charles Stark Draper Laboratory later recalled:

To blame the computer for the Apollo 11 problems is like blaming the person who spots a fire and calls the fire department. Actually, the computer was programmed to do more than recognize error conditions. A complete set of recovery programs was incorporated into the software. The software's action, in this case, was to eliminate lower priority tasks and re-establish the more important ones. The computer, rather than almost forcing an abort, prevented an abort. If the computer hadn't recognized this problem and taken recovery action, I doubt if Apollo 11 would have been the successful Moon landing it was.[69]

During the mission, the cause was diagnosed as the rendezvous radar switch being in the wrong position, causing the computer to process data from both the rendezvous and landing radars at the same time.[65] Software engineer Don Eyles concluded in a 2005 Guidance and Control Conference paper that the problem was due to a hardware design bug previously seen during testing of the first uncrewed LM in Apollo 5. Having the rendezvous radar on (so it was warmed up in case of an emergency landing abort) should have been irrelevant to the computer, but an electrical phasing mismatch between two parts of the rendezvous radar system could cause the stationary antenna to appear to the computer as dithering back and forth between two positions, depending upon how the hardware randomly powered up. The extra spurious cycle stealing, as the rendezvous radar updated an involuntary counter, caused the computer alarms.

Landing

When Armstrong again looked outside, he saw that the computer's landing target was in a boulder-strewn area just north and east of a Template:Convert/LoffAoffDbSmid crater (later determined to be West crater), so he took semi-automatic control.[70][71] Armstrong considered landing short of the boulder field so they could collect geological samples from it, but could not since their horizontal velocity was too high. Throughout the descent, Aldrin called out navigation data to Armstrong, who was busy piloting Eagle. Now 107 feet (33 m) above the surface, Armstrong knew their propellant supply was dwindling and was determined to land at the first possible landing site.[72]

Armstrong found a clear patch of ground and maneuvered the spacecraft towards it. As he got closer, now 250 feet (76 m) above the surface, he discovered his new landing site had a crater in it. He cleared the crater and found another patch of level ground. They were now 100 feet (30 m) from the surface, with only 90 seconds of propellant remaining. Lunar dust kicked up by the LM's engine began to impair his ability to determine the spacecraft's motion. Some large rocks jutted out of the dust cloud, and Armstrong focused on them during his descent so he could determine the spacecraft's speed.[73]

A light informed Aldrin that at least one of the 67-inch (170 cm) probes hanging from Eagle's footpads had touched the surface a few moments before the landing and he said: "Contact light!" Armstrong was supposed to immediately shut the engine down, as the engineers suspected the pressure caused by the engine's own exhaust reflecting off the lunar surface could make it explode, but he forgot. Three seconds later, Eagle landed and Armstrong shut the engine down.[74] Aldrin immediately said "Okay, engine stop. ACA—out of detent." Armstrong acknowledged: "Out of detent. Auto." Aldrin continued: "Mode control—both auto. Descent engine command override off. Engine arm—off. 413 is in."[75]

ACA was the Attitude Control Assembly—the LM's control stick. Output went to the LGC to command the reaction control system (RCS) jets to fire. "Out of Detent" meant the stick had moved away from its centered position; it was spring-centered like the turn indicator in a car. LGC address 413 contained the variable that indicated the LM had landed.

Eagle landed at 20:17:40 UTC on Sunday July 20 with 216 pounds (98 kg) of usable fuel remaining. Information available to the crew and mission controllers during the landing showed the LM had enough fuel for another 25 seconds of powered flight before an abort without touchdown would have become unsafe,[4] but post-mission analysis showed that the real figure was probably closer to 50 seconds.[76] Apollo 11 landed with less fuel than most subsequent missions, and the astronauts encountered a premature low fuel warning. This was later found to be the result of greater propellant 'slosh' than expected, uncovering a fuel sensor. On subsequent missions, extra anti-slosh baffles were added to the tanks to prevent this.

Armstrong acknowledged Aldrin's completion of the post landing checklist with "Engine arm is off," before responding to the CAPCOM, Charles Duke, with the words, "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed." Armstrong's unrehearsed change of call sign from "Eagle" to "Tranquility Base" emphasized to listeners that landing was complete and successful. Duke mispronounced his reply as he expressed the relief at Mission Control: "Roger, Twan—Tranquility, we copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We're breathing again. Thanks a lot."[77]

Two and a half hours after landing, before preparations began for the EVA, Aldrin radioed to Earth:

This is the LM pilot. I'd like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way.[78]

He then took communion privately. At this time NASA was still fighting a lawsuit brought by atheist Madalyn Murray O'Hair (who had objected to the Apollo 8 crew reading from the Book of Genesis) demanding that their astronauts refrain from broadcasting religious activities while in space. As such, Aldrin chose to refrain from directly mentioning taking communion on the Moon. Aldrin was an elder at the Webster Presbyterian Church, and his communion kit was prepared by the pastor of the church, Dean Woodruff. Webster Presbyterian possesses the chalice used on the Moon and commemorates the event each year on the Sunday closest to July 20.[79] The schedule for the mission called for the astronauts to follow the landing with a five-hour sleep period, but they chose to begin preparations for the EVA early, thinking they would be unable to sleep.[65]

Lunar surface operations

Preparations for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to walk on the Moon began at 23:43.[4] These took longer than expected; three and a half hours instead of two. During training on Earth, everything required had been neatly laid out in advance, but on the Moon the cabin contained a large number of other items as well, such as checklists, food packets, and tools.[65] Six hours and thirty-nine minutes after landing Armstrong and Aldrin were ready to go outside, and Eagle was depressurized.[80]

Eagle's hatch was opened at 02:39:33.[4] Armstrong initially had some difficulties squeezing through the hatch with his portable life support system (PLSS).[81] Some of the highest heart rates recorded from Apollo astronauts occurred during LM egress and ingress.[82] At 02:51 Armstrong began his descent to the lunar surface. The remote control unit on his chest kept him from seeing his feet. Climbing down the nine-rung ladder, Armstrong pulled a D-ring to deploy the modular equipment stowage assembly (MESA) folded against Eagle's side and activate the TV camera.[5]

Apollo 11 used slow-scan television (TV) incompatible with broadcast TV, so it was displayed on a special monitor, and a conventional TV camera viewed this monitor, significantly reducing the quality of the picture.[83] The signal was received at Goldstone in the United States, but with better fidelity by Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station near Canberra in Australia. Minutes later the feed was switched to the more sensitive Parkes radio telescope in Australia.[84] Despite some technical and weather difficulties, ghostly black and white images of the first lunar EVA were received and broadcast to at least 600 million people on Earth.[84] Copies of this video in broadcast format were saved and are widely available, but recordings of the original slow scan source transmission from the lunar surface were likely destroyed during routine magnetic tape re-use at NASA.

While still on the ladder, Armstrong uncovered a plaque mounted on the LM descent stage bearing two drawings of Earth (of the Western and Eastern Hemispheres), an inscription, and signatures of the astronauts and President Nixon. The inscription read:

Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon July 1969, A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.

At the behest of the Nixon administration to add a reference to God, NASA included the vague date as a reason to include A.D., which stands for Anno Domini, "in the year of our Lord" (although it should have been placed before the year, not after).[85]

After describing the surface dust as "very fine-grained" and "almost like a powder", at 02:56:15,[86] six and a half hours after landing, Armstrong stepped off Eagle's footpad and declared: "That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."[4][87]

Armstrong intended to say "That's one small step for a man", but the word "a" is not audible in the transmission, and thus was not initially reported by most observers of the live broadcast. When later asked about his quote, Armstrong said he believed he said "for a man", and subsequent printed versions of the quote included the "a" in square brackets. One explanation for the absence may be that his accent caused him to slur the words "for a" together; another is the intermittent nature of the audio and video links to Earth, partly because of storms near Parkes Observatory. More recent digital analysis of the tape claims to reveal the "a" may have been spoken but obscured by static.[88][89]

About seven minutes after stepping onto the Moon's surface, Armstrong collected a contingency soil sample using a sample bag on a stick. He then folded the bag and tucked it into a pocket on his right thigh. This was to guarantee there would be some lunar soil brought back in case an emergency required the astronauts to abandon the EVA and return to the LM.[90] Twelve minutes after the sample was collected,[4] he removed the TV camera from the MESA and made a panoramic sweep, then mounted it on a tripod. The TV camera cable remained partly coiled and presented a tripping hazard throughout the EVA. Still photography was accomplished with a Hasselblad camera which could be operated hand held or mounted on Armstrong's Apollo space suit.[65] Aldrin joined Armstrong on the surface. He described the view with the simple phrase: "Magnificent desolation."

Armstrong said moving in the lunar gravity, one-sixth of Earth's, was "even perhaps easier than the simulations ... It's absolutely no trouble to walk around." Aldrin joined him on the surface and tested methods for moving around, including two-footed kangaroo hops. The PLSS backpack created a tendency to tip backward, but neither astronaut had serious problems maintaining balance. Loping became the preferred method of movement. The astronauts reported that they needed to plan their movements six or seven steps ahead. The fine soil was quite slippery. Aldrin remarked that moving from sunlight into Eagle's shadow produced no temperature change inside the suit, but the helmet was warmer in sunlight, so he felt cooler in shadow. The MESA failed to provide a stable work platform and was in shadow, slowing work somewhat. As they worked, the moonwalkers kicked up gray dust which soiled the outer part of their suits.[65]

The astronauts planted the Lunar Flag Assembly containing a flag of the United States on the lunar surface, in clear view of the TV camera. Aldrin remembered, "Of all the jobs I had to do on the Moon the one I wanted to go the smoothest was the flag raising."[91] But the astronauts struggled with the telescoping rod and could only jam the pole a couple of inches (5 cm) into the hard lunar surface. Aldrin was afraid it might topple in front of TV viewers. But he gave "a crisp West Point salute."[91] Before Aldrin could take a photo of Armstrong with the flag, President Richard Nixon spoke to them through a telephone-radio transmission which Nixon called "the most historic phone call ever made from the White House."[92] Nixon originally had a long speech prepared to read during the phone call, but Frank Borman, who was at the White House as a NASA liaison during Apollo 11, convinced Nixon to keep his words brief.[93]

Nixon: Hello, Neil and Buzz. I'm talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House. And this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made. I just can't tell you how proud we all are of what you've done. For every American, this has to be the proudest day of our lives. And for people all over the world, I am sure they too join with Americans in recognizing what an immense feat this is. Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man's world. And as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to Earth. For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one: one in their pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.

Armstrong: Thank you, Mr. President. It's a great honor and privilege for us to be here, representing not only the United States, but men of peace of all nations, and with interest and curiosity, and men with a vision for the future. It's an honor for us to be able to participate here today.[94]

They deployed the EASEP, which included a passive seismic experiment package used to measure moonquakes and a retroreflector array used for the lunar laser ranging experiment. Then Armstrong walked 196 feet (60 m) from the LM to snap photos at the rim of Little West Crater while Aldrin collected two core samples. He used the geologist's hammer to pound in the tubes—the only time the hammer was used on Apollo 11—but was unable to penetrate more than 6 inches (15 cm) deep. The astronauts then collected rock samples using scoops and tongs on extension handles. Many of the surface activities took longer than expected, so they had to stop documenting sample collection halfway through the allotted 34 minutes. Aldrin shoveled 6 kilograms (13 lb) of soil into the box of rocks in order to pack them in tightly.[95] Two types of rocks were found in the geological samples: basalt and breccia. Three new minerals were discovered in the rock samples collected by the astronauts: armalcolite, tranquillityite, and pyroxferroite. Armalcolite was named after Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins. All have subsequently been found on Earth.[96]

Mission Control used a coded phrase to warn Armstrong his metabolic rates were high, and that he should slow down. He was moving rapidly from task to task as time ran out. As metabolic rates remained generally lower than expected for both astronauts throughout the walk, Mission Control granted the astronauts a 15-minute extension.[97] In a 2010 interview, Armstrong explained that NASA limited the first moonwalk's time and distance because there was no empirical proof of how much cooling water the astronauts' PLSS backpacks would consume to handle their body heat generation while working on the Moon.[98]

Lunar ascent

Aldrin entered Eagle first. With some difficulty the astronauts lifted film and two sample boxes containing 21.55 kilograms (47.5 lb) of lunar surface material to the LM hatch using a flat cable pulley device called the Lunar Equipment Conveyor (LEC). This proved to be an inefficient tool, and later missions preferred to carry equipment and samples up to the LM by hand. Armstrong reminded Aldrin of a bag of memorial items in his sleeve pocket, and Aldrin tossed the bag down. Armstrong then jumped onto the ladder's third rung, and climbed into the LM. After transferring to LM life support, the explorers lightened the ascent stage for the return to lunar orbit by tossing out their PLSS backpacks, lunar overshoes, an empty Hasselblad camera, and other equipment. The hatch was closed again at 05:11:13. They then pressurized the LM and settled down to sleep.[99]

Presidential speech writer William Safire had prepared an In Event of Moon Disaster announcement for Nixon to read in the event the Apollo 11 astronauts were stranded on the Moon.[100] The remarks were in a memo from Safire to Nixon's White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, in which Safire suggested a protocol the administration might follow in reaction to such a disaster.[101][102] According to the plan, Mission Control would "close down communications" with the LM, and a clergyman would "commend their souls to the deepest of the deep" in a public ritual likened to burial at sea. The last line of the prepared text contained an allusion to Rupert Brooke's First World War poem, "The Soldier".

While moving inside the cabin, Aldrin accidentally damaged the circuit breaker that would arm the main engine for lift off from the Moon. There was a concern this would prevent firing the engine, stranding them on the Moon. A felt-tip pen was sufficient to activate the switch; had this not worked, the LM circuitry could have been reconfigured to allow firing the ascent engine.

After more than 211⁄2 hours on the lunar surface, in addition to the scientific instruments, the astronauts left behind: an Apollo 1 mission patch in memory of astronauts Roger Chaffee, Gus Grissom, and Edward White, who died when their command module caught fire during a test in January 1967; two memorial medals of Soviet cosmonauts Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin, who died in 1967 and 1968 respectively; a memorial bag containing a gold replica of an olive branch as a traditional symbol of peace; and a silicon message disk carrying the goodwill statements by Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon along with messages from leaders of 73 countries around the world.[103] The disk also carries a listing of the leadership of the US Congress, a listing of members of the four committees of the House and Senate responsible for the NASA legislation, and the names of NASA's past and present top management.[104]

After about seven hours of rest, the crew was awakened by Houston to prepare for the return flight. Two and a half hours later, at 17:54:00 UTC, they lifted off in Eagle's ascent stage to rejoin Collins aboard Columbia in lunar orbit.[4] Film taken from the LM ascent stage upon liftoff from the Moon reveals the American flag, planted some 25 feet (8 m) from the descent stage, whipping violently in the exhaust of the ascent stage engine. Aldrin looked up in time to witness the flag topple: "The ascent stage of the LM separated ... I was concentrating on the computers, and Neil was studying the attitude indicator, but I looked up long enough to see the flag fall over."[105] Subsequent Apollo missions planted their flags farther from the LM.[106]

Return

Eagle rendezvoused with Columbia at 21:24 UTC on July 21, and the two docked at 21:35. Eagle's ascent stage was jettisoned into lunar orbit at 23:41.[4] Just before the Apollo 12 flight, it was noted that Eagle was still likely to be orbiting the Moon. Later NASA reports mentioned that Eagle's orbit had decayed, resulting in it impacting in an "uncertain location" on the lunar surface.[107]

On July 23, the last night before splashdown, the three astronauts made a television broadcast in which Collins commented:

The Saturn V rocket which put us in orbit is an incredibly complicated piece of machinery, every piece of which worked flawlessly ... We have always had confidence that this equipment will work properly. All this is possible only through the blood, sweat, and tears of a number of people ... All you see is the three of us, but beneath the surface are thousands and thousands of others, and to all of those, I would like to say, "Thank you very much."[105]

Aldrin added:

This has been far more than three men on a mission to the Moon; more, still, than the efforts of a government and industry team; more, even, than the efforts of one nation. We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown ... Personally, in reflecting on the events of the past several days, a verse from Psalms comes to mind. "When I consider the heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained; What is man that Thou art mindful of him?"[105][108]

Armstrong concluded:

The responsibility for this flight lies first with history and with the giants of science who have preceded this effort; next with the American people, who have, through their will, indicated their desire; next with four administrations and their Congresses, for implementing that will; and then, with the agency and industry teams that built our spacecraft, the Saturn, the Columbia, the Eagle, and the little EMU, the spacesuit and backpack that was our small spacecraft out on the lunar surface. We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft. To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11.[105]

On the return to Earth, a bearing at the Guam tracking station failed, potentially preventing communication on the last segment of the Earth return. A regular repair was not possible in the available time but the station director, Charles Force, had his ten-year-old son Greg use his small hands to reach into the housing and pack it with grease. Greg was later thanked by Armstrong.[109]

Splashdown and quarantine

Before dawn on July 24, Hornet launched four Sea King helicopters and three Grumman E-1 Tracers. Two of the E-1s were designated as "air boss" while the third acted as a communications relay aircraft. Two of the Sea Kings carried divers and recovery equipment. The third carried photographic equipment, and the fourth carried the decontamination swimmer and the flight surgeon.[65] At 16:44 UTC (05:44 local time) Columbia's drogue parachutes were deployed. This was observed by the helicopters. Seven minutes later Columbia struck the water forcefully 2,660 km (1,440 nmi) east of Wake Island, 380 km (210 nmi) south of Johnston Atoll, and 24 km (13 nmi) from Hornet,[4] with 6 feet (1.8 m) seas and winds at 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) from the east were reported under broken clouds at 1,500 feet (460 m) with visibility of nmi at the recovery site.[110] Reconnaissance aircraft flying to the original splashdown location reported the conditions Brandli and Houston had predicted.[111]

During splashdown, Columbia landed upside down but was righted within ten minutes by flotation bags activated by the astronauts.[65] A diver from the Navy helicopter hovering above attached a sea anchor to prevent it from drifting.[112] More divers attached flotation collars to stabilize the module and positioned rafts for astronaut extraction.[113]

The divers then passed biological isolation garments (BIGs) to the astronauts, and assisted them into the life raft. The possibility of bringing back pathogens from the lunar surface was considered remote, but NASA took precautions at the recovery site. The astronauts were rubbed down with a sodium hypochlorite solution and Columbia wiped with Betadine to remove any lunar dust that might be present. The astronauts were winched on board the recovery helicopter. BIGs were worn until they reached isolation facilities on board Hornet. The raft containing decontamination materials was intentionally sunk.[65]

After touchdown on Hornet at 17:53 UTC, the helicopter was lowered by the elevator into the hangar bay, where the astronauts walked the 30 feet (9.1 m) to the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), where they would begin the Earth-based portion of their 21 days of quarantine.[114] This practice would continue for two more Apollo missions, Apollo 12 and Apollo 14, before the Moon was proven to be barren of life, and the quarantine process dropped.[115] Nixon welcomed the astronauts back to Earth. He told them: "As a result of what you've done, the world has never been closer together before."[116]

After Nixon departed, Hornet was brought alongside the 5-short-ton (Template:Convert/t LT) Columbia, which was lifted aboard by the ship's crane, placed on a dolly and moved next to the MQF. It was then attached to the MQF with a flexible tunnel, allowing the lunar samples, film, data tapes and other items to be removed. Hornet returned to Pearl Harbor, where the MQF was loaded onto a Lockheed C-141 Starlifter and airlifted to the Manned Spacecraft Center. The astronauts arrived at the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at 10:00 UTC on July 28. Columbia was taken to Ford Island for deactivation, and its pyrotechnics made safe. It was then taken to Hickham Air Force Base, from whence it was flown to Houston in a Douglas C-133 Cargomaster, reaching the Lunar Receiving Laboratory on July 30.[65]

In accordance with the Extra-Terrestrial Exposure Law, a set of regulations promulgated by NASA on July 16 to codify its quarantine protocol,[117] the astronauts continued in quarantine. After three weeks in confinement (first in the Apollo spacecraft, then in their trailer on Hornet, and finally in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory), the astronauts were given a clean bill of health.[118] On August 10, 1969, the Interagency Committee on Back Contamination met in Atlanta and lifted the quarantine on the astronauts, on those who had joined them in quarantine (NASA physician William Carpentier and MQF project engineer John Hirasaki),[119] and on Columbia itself. Loose equipment from the spacecraft remained in isolation until the lunar samples were released for study. [120]

Celebrations

On August 13, the three astronauts rode in ticker-tape parades in their honor in New York and Chicago, with an estimated six million attendees.[121] On the same evening in Los Angeles there was an official state dinner to celebrate the flight, attended by members of Congress, 44 governors, the Chief Justice of the United States, and ambassadors from 83 nations at the Century Plaza Hotel. Nixon and Agnew honored each astronaut with a presentation of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[122]

The three astronauts spoke before a joint session of Congress on September 16, 1969. They presented two US flags, one to the House of Representatives and the other to the Senate, that they had carried with them to the surface of the Moon.[123] The flag of American Samoa on Apollo 11 is on display at the Jean P. Haydon Museum in Pago Pago, the capital of American Samoa.[124]

This celebration began a 38-day world tour that brought the astronauts to 22 foreign countries and included visits with the leaders of many countries.[125] The crew toured from September 29 to November 5.[126][127] Many nations honored the first human Moon landing with special features in magazines or by issuing Apollo 11 commemorative postage stamps or coins.[128]

Legacy

Cultural significance

Humans walking on the Moon and returning safely to Earth accomplished Kennedy's goal set eight years earlier. In Mission Control during the Apollo 11 landing, Kennedy's speech flashed on the screen, followed by the words "TASK ACCOMPLISHED, July 1969." The success of Apollo 11 demonstrated the United States' technological superiority;[129] and with the success of Apollo 11, America had won the Space Race.[130]

Twenty percent of the world's population watched humans walk on the Moon for the first time. While Apollo 11 sparked the interest of the world, the follow-on Apollo missions did not hold the interest of the nation. One possible explanation was the shift in complexity. Landing someone on the Moon was an easy goal to understand; lunar geology was too abstract for the average person. Another is that Kennedy's goal of landing humans on the Moon had already been accomplished.[131] A well-defined objective helped Project Apollo accomplish its goal, but after it was completed it was hard to justify continuing the lunar missions.[132]

While most Americans were proud of their nation's achievements in space exploration, only once during the late 1960s did the Gallup Poll indicate that a majority of Americans favored "doing more" in space as opposed to "doing less". By 1973, 59 percent of those polled favored cutting spending on space exploration. The Space Race had ended, and Cold War tensions were easing as the US and Soviet Union entered the era of détente. This was also a time when inflation was rising, which put pressure on the government to reduce spending. What saved the space program was that it was one of the few government programs that had achieved something great. Drastic cuts, warned Caspar Weinberger, the deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget, might send a signal that "our best years are behind us".[133]

After the Apollo 11 mission, officials from the Soviet Union said landing humans on the Moon was dangerous and unnecessary. At the time the Soviet Union was attempting to retrieve lunar samples robotically. The Soviets publicly denied there was a race to the Moon, and indicated they were not making an attempt.[134] Mstislav Keldysh said in July 1969, "We are concentrating wholly on the creation of large satellite systems." It was revealed in 1989 that the Soviets had tried to send people to the Moon, but were unable due to technological difficulties.[135] The public's reaction in the Soviet Union was mixed. The Soviet government limited the release of information about the lunar landing, which affected the reaction. A portion of the populace did not give it any attention, and another portion was angered by it.[136]

The Apollo 11 landing is referenced in the songs "Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins" by The Byrds on the 1969 album Ballad of Easy Rider and "Coon on the Moon" by Howlin' Wolf on the 1973 album The Back Door Wolf.

Spacecraft

The Command Module Columbia went on a tour of the United States, visiting 49 state capitals, the District of Columbia, and Anchorage, Alaska.Allan Needel, "The Last Time the Command Module Columbia Toured", https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/last-time-command-module-columbia-toured, Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, February 25, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2020}}</ref> In 1971, it was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution, and was displayed at the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, DC. It was in the central Milestones of Flight exhibition hall in front of the Jefferson Drive entrance, sharing the main hall with other pioneering flight vehicles such as the Wright Flyer, Spirit of St. Louis, Bell X-1, North American X-15 and Friendship 7.[137]

Columbia was moved in 2017 to the NASM Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, to be readied for a four-city tour titled Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission. This included Space Center Houston from October 14, 2017 to March 18, 2018, the Saint Louis Science Center from April 14 to September 3, 2018, the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh from September 29, 2018 to February 18, 2019,its last location at Seattle's Museum of Flight from March 16 to September 2, 2019.[138][139] Continued renovations at the Smithsonian allowed time for an additional stop for the capsule, and it was moved to the Cincinnati Museum Center. The ribbon cutting ceremony was on September 29, 2019.[140]

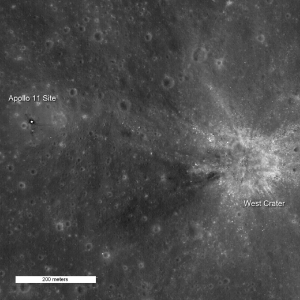

The descent stage of the LM Eagle remains on the Moon. In 2009, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) imaged the various Apollo landing sites on the surface of the Moon, for the first time with sufficient resolution to see the descent stages of the lunar modules, scientific instruments, and foot trails made by the astronauts.[141] The remains of the ascent stage lie at an unknown location on the lunar surface, after being abandoned and impacting the Moon. The location is uncertain because Eagle ascent stage was not tracked after it was jettisoned, and the lunar gravity field is sufficiently non-uniform to make the orbit of the spacecraft unpredictable after a short time.[142]

In March 2012 a team of specialists financed by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos located the F-1 engines from the S-IC stage that launched Apollo 11 into space. They were found on the Atlantic seabed using advanced sonar scanning.[143] His team brought parts of two of the five engines to the surface. In July 2013, a conservator discovered a serial number under the rust on one of the engines raised from the Atlantic, which NASA confirmed was from Apollo 11.[144][145] The S-IVB third stage which performed Apollo 11's trans-lunar injection remains in a solar orbit near to that of Earth.[146]

Moon rocks

The main repository for the Apollo Moon rocks is the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. For safekeeping, there is also a smaller collection stored at White Sands Test Facility near Las Cruces, New Mexico. Most of the rocks are stored in nitrogen to keep them free of moisture. They are handled only indirectly, using special tools. Over 100 research laboratories around the world conduct studies of the samples, and approximately 500 samples are prepared and sent to investigators every year.[147][148]

In November 1969, Nixon asked NASA to make up about 250 presentation Apollo 11 lunar sample displays for 135 nations, the fifty states of the United States and its possessions, and the United Nations. Each display included Moon dust from Apollo 11. The rice-sized particles were four small pieces of Moon soil weighing about 50 mg and were enveloped in a clear acrylic button about as big as a United States half dollar coin. This acrylic button magnified the grains of lunar dust. The Apollo 11 lunar sample displays were given out as goodwill gifts by Nixon in 1970.[149]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Sarah Loff, Apollo 11 Mission Overview NASA, May 15, 2019. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Apollo 11 (AS-506) Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ↑ David R. Williams, Apollo Landing Site CoordinatesNASA. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Richard W. Orloff, Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference NASA History Series SP-4029 (Washington, DC: NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans, 2000, ISBN 978-0160506314).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Eric Jones, One Small Step, Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, April 8, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ John M. Logsdon, The Decision to Go to the Moon: Project Apollo and the National Interest (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0226491752, 134.

- ↑ Logsdon 1976, 13–15.

- ↑ Courtney G. Brooks, James M. Grimwood, and Loyd S. Swenson, Jr. Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft SP-4205, NASA History Series (Washington, DC: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA, 1979, ISBN 978-0486467566), 1.

- ↑ Loyd S. Swenson, Jr., James M. Grimwood, and Charles C. Alexander, This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury The NASA History Series SP-4201, (Washington, DC: NASA, 1966), 101–106.

- ↑ Swenson, Grimwood, and Alexander, 134.

- ↑ Logsdon 1976, 121.

- ↑ Logsdon 1976, 112–117.

- ↑ President John F. Kennedy, Excerpt from the 'Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs' Delivered in person before a joint session of Congress May 25, 1961. NASA, May 24, 2004. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ↑ Eugene Keilen, 'Visiting Professor' Kennedy Pushes Space Age Spending The Rice Thresher, September 19, 1962. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ John F. Kennedy Moon Speech—Rice Stadium, September 12, 1962. NASA. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ Charles Fishman, What You Didn't Know About the Apollo 11 Mission. Smithsonian Magazine, June 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 15.

- ↑ John M. Logsdon, John F. Kennedy and the Race to the Moon (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, ISBN 978-0230110106), 32.

- ↑ Address at 18th U.N. General Assembly John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, September 20, 1963. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ↑ The Rendezvous That Was Almost Missed, NASA Langley Research Center Office of Public Affairs, December 1992. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 72–77.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 48–49.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 181–182, 205–208.

- ↑ Interplanetary Monitoring Platform: Engineering History and Achievements NASA, August 29, 1989, 1, 11, 134. Retrieved February 20 2020.

- ↑ Paul Ceruzzi, Apollo Guidance Computer and the First Silicon Chips Smithsonian Institution, October 14, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 214–218.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 265–272.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 274–284.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 292–300.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 303–312.

- ↑ Marcus Lindros, The Soviet Manned Lunar Program Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Jonathan Brown, Recording tracks Russia's Moon gatecrash attempt The Independent, July 3, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 374.

- ↑ James R. Hansen, First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong (New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005, ISBN 978-0743256315), 312–313.

- ↑ Michael Collins, Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys (1974; New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0815410287), 288–289.

- ↑ Walter Cunningham, The All-American Boys (ipicturebooks, 2010, ISBN 978-1876963248), 109.

- ↑ Hansen, 338–339.

- ↑ Collins, 2001, 434–435.

- ↑ Hansen, 359.

- ↑ Hansen, 359.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Mark Garcia, 50 Years Ago: Lunar Landing Sites Selected NASA, February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Edgar M. Cortright, Scouting the Moon Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, (Washington, DC: NASA SP:350), 1975, 79–102. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ↑ David Harland, Exploring the Moon: The Apollo Expeditions (London; New York: Springer, 1999, ISBN 978-1852330996), 19.

- ↑ Michael Collins, Flying to the Moon: An Astronauts Story (New York: Square Fish, 1994 (original 1976) ISBN 978-0374423568), 7.

- ↑ J.O. Cappellari, Jr., Apollo 10 Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Andrew Chaikin, A Man on the Moon: The Triumphant Story Of The Apollo Space Program (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 1994, ISBN 978-0140272017), 148.

- ↑ Chaikin, 148.

- ↑ Collins, 2001, 347.

- ↑ Buzz Aldrin and Ken Abraham, No Dream is Too High: Life Lessons from a Man who Walked on the Moon (Washington, DC :National Geographic, 2016, ISBN 978-1426216497), 57–58.

- ↑ Hansen, 363–365.

- ↑ Chaikin, 149.

- ↑ Chaikin, 150.

- ↑ James Schefter, The Race: The Uncensored Story of How America Beat Russia to the Moon (New York: Doubleday, 1999, ISBN 978-0385492539), 281.

- ↑ Hansen, 371–372.

- ↑ Charles D. Benson and William B. Faherty, Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations, (Washington, DC: NASA, 1978, ISBN 978-1470052676), 472.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 Benson and Faherty, 474-475.

- ↑ Benson and Faherty, 355–356.

- ↑ Collins, 2001, 355–357.

- ↑ David Woods, Kenneth D. McTaggart, and Frank O'Brien, Day 1, Part 1: Launch Apollo Flight Journal, January 8, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 338.

- ↑ President Richard Nixon's Daily Diary Richard Nixon Presidential Library, July 16, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Marshall Space Flight Center, Technical Information Summary, Apollo-11 (AS-506) Apollo Saturn V Space Vehicle, Document ID: 19700011707; Accession Number: 70N21012; Report Number: NASA-TM-X-62812; S&E-ASTR-S-101-69, Huntsville, AL: NASA, June 1969. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ↑ W. David Woods, Kenneth D. MacTaggart, and Frank O'Brien, Day 4, part 1: Entering Lunar Orbit Apollo Flight Journal, February 10, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Mission Press Kit NASA, July 6, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 65.00 65.01 65.02 65.03 65.04 65.05 65.06 65.07 65.08 65.09 65.10 Mission Evaluation Team, Apollo 11 Mission Report NASA, 1971. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ↑ Edgar M. Cortright (ed.), The Eagle Has landed Apollo Expeditions to the Moon SP-350, Washington, DC: NASA, 1975. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ↑ David A. Mindell, Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0262134972), 220–221

- ↑ Margaret H. Hamilton and William R. Hackler, "Universal Systems Language: Lessons Learned from Apollo" Computer 41 (12) December 2008, 34–43.

- ↑ Margaret H. Hamilton, "Computer Got Loaded", Datamation, March 1, 1971, 13.

- ↑ Chaikin, 196.

- ↑ Mindell, 195–197.

- ↑ Chaikin, 197.

- ↑ Chaikin, 198–199.

- ↑ Chaikin, 199.

- ↑ Mindell, 226.

- ↑ Paul Fjeld, The Biggest Myth about the First Moon Landing Horizons 38(6), June 2013, 5–6. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ James Donovan, Shoot for the Moon: The Space Race and the Extraordinary Voyage of Apollo 11 (Little, Brown and Company, 2019, ISBN 978-0316341783).

- ↑ Eric Jones, Post-landing Activities Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Chaikin, 204, 623.

- ↑ Cortright, 215.

- ↑ Eric M. Jones and Ken Glover, First Steps Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Ricahrd S. Johnston, Lawrence F. Dietlin and Charles A. Berry (eds.), Biomedical Results of Apollo (Washington, DC: NASA, 1975), 115–120. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Richard Macey, One giant blunder for mankind: how NASA lost Moon pictures The Sydney Morning Herald, August 5, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 John M. Sarkissian, On Eagle's Wings: The Parkes Observatory's Support of the Apollo 11 Mission Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 18(3), 2001. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ William Gardner, Before the Fall: An Inside View of the Pre-Watergate White House (London; New York: Routledge Press, 2017, 978-1351314589), 143.

- ↑ Jacob Stern, One Small Controversy About Neil Armstrong's Giant Leap—When, exactly, did the astronaut set foot on the moon? No one knows The Atlantic, July 23, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Shelley Canright, Apollo Moon Landing—35th Anniversary NASA, July 15, 2004. Retrieved February 20, 2020. Includes the "a" article as intended.

- ↑ Armstrong 'got Moon quote right' BBC News', October 2, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Pallab Ghosh, Armstrong's 'poetic' slip on Moon BBC News, June 3, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Charles Meyer, Contingency Soil Lunar Sample Compendium , NASA, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 "A Flag on the Moon" The Attic. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Apollo 11 and Nixon, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals/apollo11.html "The President held an interplanetary conversation with Apollo 11 Astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin on the Moon" National Archives and Records Administration, March 1996. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Frank Borman and Robert J. Serling, Countdown: An Autobiography (New York: Silver Arrow, 1988, ISBN 978-0688079291, 237–238.

- ↑ "Richard Nixon: Telephone Conversation With the Apollo 11 Astronauts on the Moon" The American Presidency Project, July 20, 1969. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ Harland, 28–29.

- ↑ University of Western Australia, Moon-walk mineral discovered in Western Australia Science Daily, January 17, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Eric M. Jones, EASEP Deployment and Closeout Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Neil Armstrong Explains His Famous Apollo 11 Moonwalk" Space.com, December 10, 2010. February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Eric M. Jones, "Trying to Rest", Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ White House 'Lost In Space' Scenarios The Smoking Gun. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Jim Mann, "The Story of a Tragedy That Was Not to Be" Los Angeles Times, July 7, 1999. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ William Safire, "Essay; Disaster Never Came" The New York Times, July 12, 1999. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "The untold story: how one small silicon disc delivered a giant message to the Moon" November 15, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages" NASA, July 13, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 105.3 Michael Collins and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. "The Eagle Has landed", Apollo Expeditions to the Moon SP-350, Cortright, Edgar M. (ed.). Washington, DC: NASA, 1975, 203–224. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ↑ "American flags still standing on the Moon, say scientists", The Daily Telegraph, June 30, 2012.

- ↑ David R. Williams, "Apollo Tables" NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Psalms 8:3–4 KJV Retrieved February 22, 2020

- ↑ Rachel Rodriguez, "The 10-year-old who helped Apollo 11, 40 years later" CNN, July 20, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "SMG Weather History—Apollo Program", NOAA. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Jeremy Deaton, 'They would get killed': The weather forecast that saved Apollo 11 The Washington Post, July 18, 2019.

- ↑ Scott W. Carmichael, Moon Men Return: USS Hornet and the Recovery of the Apollo 11 Astronauts (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1591141105), 184–185.

- ↑ Carmichael, 186–188.

- ↑ Carmichael, 199–200.

- ↑ Johnston, Dietlein and Berry, 406–424.

- ↑ Remarks to Apollo 11 Astronauts Aboard the U.S.S. Hornet Following Completion of Their Lunar Mission The American Presidency Project, July 24, 1969. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ Extra-Terrestrial Exposure, 34 Fed. Reg. 11975, July 16, 1969, codified at 14 C.F.R. pt. 1200. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ "A Front Row Seat For History" NASA, July 15, 2004. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Carmichael, 118.

- ↑ Ivan D. Ertel, Roland W. Newkirk, and Courtney G. Brooks, Man Circles the Moon, the Eagle Lands, and Manned Lunar Exploration The Apollo Spacecraft—A Chronology SP-4009, Vol. IV. Part 3 (1969 3rd quarter), Washington, DC: NASA, 1978. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ↑ Richard M. Nixon, "Remarks at a Dinner in Los Angeles Honoring the Apollo 11 Astronauts" The American Presidency Project, August 13, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Merriman Smith, "Astronauts Awed by the Acclaim" The Honolulu Advertiser, August 14, 1969, 1. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ "The Apollo 11 Crew Members Appear Before a Joint Meeting of Congress" United States House of Representatives, September 19, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Jean P. Haydon Museum" Fodor's Travel. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Apollo 11 Crew Starts World Tour" Associated Press, September 29, 1969, 1. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ↑ "Japan's Sato Gives Medals to Apollo Crew" Los Angeles Times, November 5, 1969, 20. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ↑ "Australia Welcomes Apollo 11 Heroes" The Sydney Morning Herald, November 1, 1969, 1. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ↑ "Lunar Missions: Apollo 11" Archived October 24, 2008. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ↑ Roger D. Lanius, "Project Apollo: A Retrospective Analysis". Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Andrew Chaikin, "Live from the Moon: The Societal Impact of Apollo, Societal Impact of Spaceflight, Steven J. Dick and Roger D. Launius, eds., NASA SP-4801, 2007, 57. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ Chaikin, 2007, 58.

- ↑ "Apollo 11" History, August 23, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Howard E. McCurdy, Space and the American Imagination (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997, ISBN 978-1560987642), 106–107.

- ↑ Chaikin, 1994, 631.

- ↑ John Noble Wilford, "Russians Finally Admit They Lost Race to Moon" New York Times, December 18, 1989. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ↑ Saswato R. Das, "The Moon Landing through Soviet Eyes: A Q&A with Sergei Khrushchev, son of former premier Nikita Khrushchev" Scientific American, July 16, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Museum in DC" Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, May 3, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Apollo 11 Command Module, 'Columbia'" Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

- ↑ Rebecca Makse, "Apollo 11 Moonship To Go On Tour" Air and Space Magazine, February 22, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Neil Armstrong's sons help open exhibit of father's spacecraft in Ohio" September 30, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "LRO Sees Apollo Landing Sites" NASA, July 17, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Location of Apollo Lunar Modules" Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Amazon boss Jeff Bezos 'finds Apollo 11 Moon engines'" BBC News, March 28, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Emi Kolawole, "Bezos Expeditions retrieves and identifies Apollo 11 engine #5, NASA confirms identity" The Washington Post, July 19, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Apollo 11 engine find confirmed" Albuquerque Journal, July 21, 2013, 5. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ↑ Apollo 11 SIVB NSSDCA/COSPAR ID: 1969-059B NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility" NASA. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Kristen Flavin, "The mystery of the missing Moon rocks" World, September 10, 2016.

- ↑ Robert Pearlman, "Where today are the Apollo 11 goodwill lunar sample displays? collectSPACE. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aldrin, Buzz, and Ken Abraham. No Dream is Too High: Life Lessons from a Man who Walked on the Moon. Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2016. ISBN 978-1426216497

- Bates, James R., W.W. Lauderdale, and Harold Kernaghan. "ALSEP Termination Report" RP-1036, Washington, DC: NASA, April 1979. Retrieved on February 28, 2020.

- Benson, Charles D., and William B. Faherty. Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. Washington, DC: NASA, 1978, ISBN 978-1470052676

- Bilstein, Roger E. "Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicle", SP=4206 NASA History Series, Washington, DC: NASA, 1980. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Borman, Frank and Robert J. Serling. Countdown: An Autobiography. New York: Silver Arrow, 1988. ISBN 978-0688079291

- Brooks, Courtney G., James M. Grimwood, and Loyd S. Swenson, Jr. Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. SP-4205, NASA History Series, Washington, DC: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA, 1979. ISBN 978-0486467566

- Cappellari, J.O. Jr., "Where on the Moon? An Apollo Systems Engineering Problem." Bell System Technical Journal 51(5) (June 1972): 955–1126.

- Carmichael, Scott W. Moon Men Return: USS Hornet and the Recovery of the Apollo 11 Astronauts. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1591141105

- Chaikin, Andrew. A Man on the Moon: The Triumphant Story Of The Apollo Space Program. New York: Penguin Group, 1994. ISBN 978-0140272017

- Chaikin, Andrew, "Live from the Moon: The Societal Impact of Apollo", Societal Impact of Spaceflight, SP-4801, Dick, Stephen J., and Roger D. Lanius (eds.). Washington, DC: NASA, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Collins, Michael and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. "The Eagle Has landed," Apollo Expeditions to the Moon SP-350, Cortright, Edgar M. (ed.). Washington, DC: NASA, 1975, 203–224. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Collins, Michael. Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001 (original 1974). ISBN 978-0815410287

- Collins, Michael. Flying to the Moon: An Astronauts Story. New York: Square Fish, 1994 (original 1976). ISBN 978-0374423568

- Cortright, Edgar M. "Scouting the Moon", Apollo Expeditions to the Moon. Washington, DC:NASA SP:350, 1975, 79–102. Retrieved on February 23, 2020.

- Cunningham, Walter. The All-American Boys (ipicturebooks, 2010, (original 1977) ISBN 978-1876963248

- Donovan, James. Shoot for the Moon: The Space Race and the Extraordinary Voyage of Apollo 11. Little, Brown and Company, 2019. ISBN 978-0316341783

- Ertel, Ivan D., Newkirk, Roland W. and Brooks, Courtney G. Man Circles the Moon, the Eagle Lands, and Manned Lunar Exploration The Apollo Spacecraft—A Chronology SP-4009, Vol. IV. Part 3 (1969 3rd quarter), Washington, DC:NASA, 1978. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- Gardner, William, Before the Fall: An Inside View of the Pre-Watergate White House (London, New York: Routledge, 2017, ISBN 978-1351314589

- Hamilton, Margaret H. and Hackler, William R., "Universal Systems Language: Lessons Learned from Apollo" Computer 41 (12) December 2008, 34–43

- Hansen, James R., First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005, ISBN 978-0743256315

- Harland, David, Exploring the Moon: The Apollo Expeditions (London; New York: Springer, 1999, ISBN 978-1852330996

- Johnston, Richard S., Dietlein, Lawrence F. and Berry, Charles A. eds., "Biomedical Results of Apollo", SP-368, Washington, DC: NASA, 1975. Retrieved February 28, 2020.