Astarte

Astarte (from Greek Αστάρτη—Astártē) was a major goddess as known from Northwestern Semitic regions, closely related in name, origins, and functions with the goddess Ishtar in Mesopotamian texts. Other renderings and transliterations of her name include ‘Ashtart, Ashtoreth, Atirat, and As-tar-tú, among others.

‘Ashtart was connected with the fertility of crops and cattle, sexuality, and war. Her symbols were the lion, the horse, the sphinx, the dove, and a star within a circle indicating the planet Venus. Pictorial representations often show her naked. In the Ugartic texts of Canaan she is closely associated with Ba'al, the chief deity of the Canaanite pantheon during the period of the Israelite monarchy. In the Bible she is frequently mentioned as Ashtoreth, a Canaanite goddess whom the Israelites were much tempted to worship against God's will.

‘Ashtart was adopted by Egyptians, and later by the Greeks, who eventually gave her the name of Aphrodite.

‘Ashtart Ugarit in Judea

‘Ashtart appears in Ugaritic texts under the name ‘Athtart. Here, she ‘asks Ba‘al to "scatter" the sea-god Yamm after Ba‘al's successful rebellion against him. Earlier, ‘Athtart and her sister and Anat together restrain Ba‘al from attacking Yamm's messengers. She was known as "She of the Womb," and was thus a goddess of sexuality, and of the fertility of women and nature. Her other epithets include ‘Athtart of the Field, The Strong One, and Face of Ba‘al. Her name and functions are clearly related to the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar, who, like ‘Athtart, was associated with the planet Venus. She is sometimes depicted, like her sister Anat, as a war-goddess, robed in flames, armed with a sword and arrows. Acacia and cypress trees were sacred to her. She was the chief goddess of Tyre, Sidon and Byblos.

Astarte in the Bible was one of the Canaanite deities whom the Israelites must abhor. Astarte, or Ashtoret in Hebrew, was the principal goddess of the Phoenicians, representing the productive power of nature. Her worship was fairly widespread in Israel, and she may have been seen as the female counterpart of consort of the Israelite god Yahweh, as well as of Ba'al, with whom Yahweh could easily have been confused in the popular imagination. Genesis 49:25 preserves an ancient blessing that may have once been associated with Astarte or Ashera:

The Almighty (Shaddai)… blesses you with blessings of the heavens above, blessings of the deep that lies below, blessings of the breast and womb.

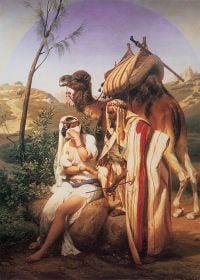

In some cases Astarte was associated with sacred prostitution, as is also the case with Ishtar. In the Book of Genesis, the Jewish patriarch Judah is portrayed as having sexual intercourse with his daughter-in-law Tamar, who has disguised herself as a sacred prostitute—most probably of Astarte—at the town of Timnath; and from this union the lineage of Judah is perpetuated.

The biblical writers speak against Astarte frequently, citing Israelite worship of her as the cause of God's abandonment of His people during the period of judges:

They forsook the Lord, the God of their fathers, who had brought them out of Egypt. They followed and worshiped various gods of the peoples around them. They provoked the Lord to anger because they forsook him and served Baal and the Ashtoreths. In his anger against Israel the Lord handed them over to raiders who plundered them. (Judges 2:12-14)

1 Samuel 12:10 depicts the Israelites as repenting for serving "The Baals and the Ashtoreths." The head of the dead King Saul was placed by the Philistines in the "temple of the Ashtoreths" (1 Samuel 31:10). King Solomon's fall from grace is blamed on his worship of Ashtoreth (1 Kings 11:4-6).

Astarte may also be the "Queen of Heaven" spoken of by the prophet Jeremiah several centuries later during the seventh or early sixth century B.C.E. Here, the people of Judah fear that by heeding the words of the prophets and abandoning the worship of the goddess, they have brought ruin upon themselves:

Ever since we stopped burning incense to the Queen of Heaven and pouring out drink offerings to her, we have had nothing and have been perishing by sword and famine. (Jeremiah 44:18)

Jeremiah describes her worship as a family affair: "The children gather wood, the fathers light the fire, and the women knead the dough and make cakes of bread for the Queen of Heaven." (Jeremiah 7:18) Archaeologists report finding small statuettes of a goddess, possible Astarte, in many homes through Israel and Judah during Jeremiah's time and earlier. (Dever, 2005)

The Bible also reports a campaign by King Josiah, who reigned during the early part of Jeremiah's ministry, to rid the country of Astarte worship:

The king also desecrated the high places that were east of Jerusalem on the south of the Hill of Corruption—-the ones Solomon king of Israel had built for Ashtoreth the vile goddess of the Sidonians, for Chemosh the vile god of Moab, and for Molech the detestable god of the people of Ammon. Josiah smashed the sacred stones and cut down the Asherah poles and covered the sites with human bones. (2 Kings 23:13-14)

Later attitudes

The Masoretic rendering of the Hebrew Bible indicates the pronunciation as ‘Aštōret, probably because the two last syllables have here been pointed with the vowels belonging to bōshet—"abomination"—to indicate that word should be substituted when reading. The plural form is pointed ‘Aštārōt.

In later Jewish mythology, Ashtoreth is interpreted as a female demon of lust. The name Asherah may also be confused with Ashtoreth. In addition "the ashtoreths" may refer to goddesses in general, and "the asherim" often refer to sacred pillars (or trees) erected next to Israelite altars.

In Christian demonology, Ashtoreth is connected to Friday, and visually represented as a young woman with a cow's horns on her head.

‘Ashtart in Egypt

‘Ashtart first appears in Ancient Egypt beginning with the reign of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt along with other deities who were worshiped by northwest semitic people. She was a lunar goddess adopted by the Egyptians as a daughter of Ra or Ptah. She was especially worshiped in her aspect as a war goddess, often paired with the semitic goddess Anat. In the Contest Between Horus and Set, these two goddesses appear as daughters of Re and are given in marriage to the god Set, here identified with the Semitic name Hadad.

‘Ashtart was often conflated, at least in part, with Isis to judge from the many images found of ‘Ashtart suckling a small child. Indeed there is a statue of the sixth century B.C.E. in the Cairo Museum, which would normally be taken as portraying Isis with her child Horus on her knee and which in every detail of iconography follows normal Egyptian conventions but the dedicatory inscription reads: "Gersaphon, son of Azor, son of Slrt, man of Lydda, for his Lady, for ‘Ashtart." (See G. Daressy, (1905) pl. LXI (CGC 39291).)

‘Ashtart in Sanchuniathon

In the description of the Phoenician pantheon ascribed to Sanchuniathon by the fourth century C.E. Christian bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, ‘Ashtart appears as a daughter of Sky and Earth and sister of the semitic god El. After El overthrows and banishes his father Sky, the older deity sends to El his "virgin daughter" ‘Ashtart, intending a trick, along with her sisters Asherah and the goddess who will later be called Ba‘alat Gebul, "the Lady of Byblos." It seems that this trick does not work as all three become wives of their brother El. ‘Ashtart bears seven daughters to El who appear under Greek names as the Titanides or Artemides. She also bears two sons named Pothos, "Longing" and Eros, "Desire."

Later, with El's consent, ‘Ashtart and Hadad (equivalent to Baal in Canaanite mythology) reign over the land together. ‘Ashtart, puts the head of a bull on her own head to symbolize her sovereignty. Wandering through the world ‘Ashtart takes up a star that has fallen from the sky and consecrates it at Tyre.

Other associations

Many scholars see a basis for the opinion that the Greek name Aphrodite (especially Aphrodite Erycina) is another term for Astarte. Herodotus wrote that the religious community of Aphrodite originated in Phoenicia and came to the Greeks from there. He also wrote about the world's largest temple of Aphrodite, in one of the Phoenician cities.

Other major centers of ‘Ashtart's worship were Sidon, Tyre, and Byblos. Coins from Sidon portray a chariot in which a globe appears, presumably a stone representing ‘Ashtart. At Beirut coins show Poseidon, Astarte, and Eshmun worshiped together. Connection to planet Venus is another similarity to the Aphrodite religious community, apparently from the Mesopotamian Goddess Ishtar. Doves being sacrificed to her is another.

Other places of her worship included Malta and Eryx in Sicily, from where she became known to the Romans as Venus Erycina. A bilingual inscription on the Pyrgi Tablets dating to about 500 B.C.E. found near Caere in Etruria equates ‘Ashtart with Etruscan Uni-Astre, that is Juno. At Carthage ‘Ashtart was worshiped alongside the goddess Tanit. The Syrian goddess Atargatis (Semitic form ‘Atar‘atah) was generally equated with ‘Ashtart.

In the Christian tradition Saint Quiteria may have originated from a title that the Phoenicians gave to the goddess Astarte: Kythere, Kyteria, or Kuteria, which means "the red one." Some believe the saint, represented in icons dressed in red, may be nothing more than a Christianized version of Astarte. Christian tradition holds that she was merely named for the goddess by her pagan father.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ashtoreth in the Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- Campbell, Joseph, Occidental Mythology: The Masks of God, Volume III, Penguin Reissue edition 1991. ISBN 014019441X

- Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. Harvard University Press 1973. ISBN 978-0674091764

- Daressy, G. Statues de divinités, vol. II. Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 1905.

- Day, John. Yahweh & the Gods & Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press, 2000. ISBN 1850759863

- Dever, William G., Did God Have A Wife? Archeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel, William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005. ISBN 0802828523

- Gibson, J. C. L. Canaanite Myths and Legends, T. & T. Clark: Released 2000. ISBN 0567023516

- Harden, Donald. The Phoenicians, 2nd ed., revised, London: Penguin, 1980. ISBN 0140213759

- Shadrach, Nineveh. Codex of Love: Reflections From The Heart of Ishtar, Ishtar Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0973593113

- Wyatt, N. Religious Texts from Ugarit, Sheffield Academic Press, Revised edition, 2003. ISBN 978-0826460486

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.