Balaam

Balaam (Hebrew: ◊Ď÷ī÷ľ◊ú÷į◊Ę÷ł◊Ě, Bil Ľam) was a non-Israelite prophet in the Hebrew Bible, his story occurring toward the end of the Book of Numbers. The etymology of his name is uncertain. His story takes place near the end of the life of Moses. He is identified as "son of Beor," who was hired by King Balak of Moab to curse the Israelites who had massed near the eastern border of Canaan and had defeated two of his neighboring kings. Balaam, however, becomes inspired by God and insists on blessing Israel instead. He is perhaps best known for the episode in which his donkey sees an angel on the road, comes to a stop, and suddenly begins to argue with Balaam, who does not perceive the angel's presence. Despite his blessing Israel on three occasions, Balaam was later blamed for seducing the Israelites to sin by engaging in sexual misconduct and idolatry at Peor. He therefore was killed by Israelite forces during a battle against the Midianites.

In rabbinical tradition, Balaam is seen both as a true prophet of God for the Gentiles and as a heathen sorcerer who ranks among the most evil men in history. Modern scholarship accounts the mixed biblical portrait of Balaam by explaining that the Book of Numbers preserves stories about him from two separate sources, one of which views him positively, while the other sees him as evil. Contained within the legend of Balaam are prophetic poems considered to be more ancient than most other biblical literature. While he remains an enigmatic figure, Balaam is certainly one of the most intriguing characters in the Bible.

The stories

Balaam and Balak

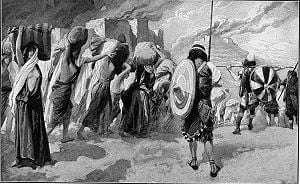

The main story of Balaam occurs during the sojourn of the Israelites in the plains of Moab, east of the Jordan River. The events take place at the close of 40 years of wandering, shortly before the death of Moses and the crossing of the Jordan into Canaan proper. The Israelites have already defeated two kings on this side of the Jordan: Sihon, king of the Amorites, and Og, king of Bashan. Balak, king of Moab, consequently becomes alarmed, and sends elders of Moab and of Midian to the prophet Balaam son of Beor, in order to induce him to come and curse Israel.

Balaam sends back word that Yahweh will not allow him to go, as God has revealed to him via a nocturnal dream, that "these people are blessed" (Num. 22:12). Moab consequently sends higher ranking "princes" and offers Balaam riches and other boons. He resists on the grounds that he must not disobey "Yahweh my God." However, during the following night, God tells Balaam to go with them.

Balaam thus sets out on his donkey to go to Balak, but an angel tries to prevent him.[1] At first the angel is seen only by the ass Balaam is riding, which tries to avoid the otherwise invisible angel. After Balaam starts punishing the ass for refusing to move, it is miraculously‚ÄĒand possibly comically‚ÄĒgiven the power to speak to Balaam. It complains about Balaam's treatment, saying: "What have I done to you to make you beat me these three times?" At this point, Balaam is allowed to see the angel, who informs him that the ass is the only reason the angel did not kill Balaam. Balaam immediately repents, but is told to go on.

The angel repeats God's previous instructions to Balaam, who then continues his journey and meets Balak as planned. Balak prepares seven altars and they go to a high place, where they offer sacrifices on seven altars.[2]

God inspires Balaam with the following prophetic message:

How can I curse those whom God has not cursed? How can I denounce those whom the Lord has not denounced?… Who can count the dust of Jacob or number the fourth part of Israel?

Let me die the death of the righteous, and may my end be like theirs! (Num. 23:8-10)

Balak remonstrates, but Balaam reminds him that he can only speak the words put in his mouth by God, so Balak takes him to another high place at Pisgah, to try again. Building another seven altars here, and making sacrifices on each, Balaam provides another prophecy blessing Israel, declaring: "There is no sorcery against Jacob, no divination against Israel."

The now very frustrated Balak takes Balaam to the high place at Peor. After the seven more sacrifices there, Balaam decides not to seek enchantments but instead looks upon the Israelites from the peak. The spirit of God comes upon Balaam once more and he delivers a third positive prophecy concerning Israel:

How beautiful are your tents, O Jacob, your dwelling places, O Israel! …May those who bless you be blessed and those who curse you be cursed! (Num. 24:5-9)

Balak's anger rises to the point where he threatens Balaam, refusing to pay him for his services, and ordering him to leave. Balaam, however, gets the last word, as he declares a prophecy of doom against Moab:

The oracle of one who hears the words of God,

who has knowledge from the Most High, who sees a vision from the Almighty, who falls prostrate, and whose eyes are opened: I see him, but not now; I behold him, but not near. A star will come out of Jacob; a scepter will rise out of Israel. He will crush the foreheads of Moab,

the skulls of all the sons of Sheth.

Balak and Balaam then each depart to their respective homes.

Balaam and the Midianites

While one might expect Balaam to be viewed positively by the Israelites for his brave and prophetic deeds on their behalf, such is not the case. Encamped at Shittim, the Israelites commit sexual sin with the women of Moab and join them in worshiping the Baal of Peor, a deity named for one of the high places where Balaam had blessed Israel. God commands Moses to execute all the participants in this episode. The priest Phinehas takes a spear and with one thrust slays both an Israelite leader and his Midianite wife, a local princess.

Later, God commands a war of "vengeance" against Midian. An Israelite force of 12,000 carries out the task with Phinehas as their standard-bearer. They kill "every man," of the opposition, including five Midianite kings and the unfortunate Balaam, whom Moses blames for the sin of Israel at Peor. When Midianite women are taken captive instead of being slaughtered by the Israelite soldiers, Moses demands:

Have you allowed all the women to live? They were the ones who followed Balaam's advice and were the means of turning the Israelites away from the Lord in what happened at Peor. Now kill all the boys. And kill every woman who has slept with a man, but save for yourselves every girl who has never slept with a man. (Numbers 31:15-18)

Balaam in rabbinic literature

Like the biblical story itself, rabbinical tradition about Balaam is mixed. The positive tradition gives him a place of great honor as the a type of Moses for the Gentiles, the greatest prophet who ever came from a non-Jewish population, including even the righteous Job (Talmud, B. B. 15b). In this tradition, Balaam had acquired a position among the non-Jews as exalted as that of Moses among the Israelites (Midrash Numbers Rabbah 20). At first he was a mere interpreter of dreams, later becoming a magician, and finally a prophet of the true God. The Talmud also recounts that when the Law was given to Israel at Sinai, a mighty voice shook the foundations of the earth, so much so that all kings trembled. They turned to Balaam, inquiring whether this upheaval of nature portended a second Great Flood. The prophet assured them that what they heard was the voice of God, giving the sacred Law to the Israelites (Zeb. 116a).

Even the a negative view of Balaam in the Talmud, recognizes that he possessed an amazing talent‚ÄĒto ascertain the exact moment when God would be angry‚ÄĒa gift bestowed upon no other creature. Balaam's intention was to curse the Israelites at that very moment, and thus cause God himself to destroy them. However, God restrained His anger in order to baffle the wicked prophet and to save the nation from extermination (Berachot 7a). Balaam is pictured as blind in one eye and lame in one foot (Sanhedrin 105a). His disciples were distinguished by three morally corrupt qualities: an evil eye, a haughty bearing and an avaricious spirit (Ab. v. 19). When Balaam saw that he could not curse the children of Israel, he advised Balak to tempt the Hebrew nation to immoral acts and, through these, to the worship the Baal of Peor. Thus, Balaam is held responsible for the Israelites' behavior during the "heresy of Peor," indirectly causing the death of 24,000 victims of the plague which God sent as punishment (San. 106a).

The first century C.E. Jewish historian Josephus speaks of Balaam as the best prophet of his time, but adds that he had a weakness in resisting temptation. Philo of Alexandria describes him in the Life of Moses as a great magician.

While speaking animals are a common feature of folklore, the only other case in the Old Testament is that of the serpent in Eden. Classical Jewish commentators, such as Maimonides, taught that a reader should not take this part of the story literally.

Balaam in the New Testament

In Rev. 2:14 we read of false teachers at Pergamum who adhered to the "teaching of Balaam, who taught Balak to cast a stumbling-block before the children of Israel, to eat things sacrificed to idols, and to commit fornication."

Balaam also figures as an example of a false teacher in both 2 Peter 2:15 and in Jude 1:11. In both of these verses, Balaam is cited as an example of a false prophet motivated by greed or avarice. These references harken to King Balak's attempt to pay Balaam to curse his enemies (Israel). The implication is that although God intervenes and makes Balaam deliver blessings instead of curses, Balaam was normally a prophet for hire, specializing in curses. The verses in 2 Peter and Jude are warnings to the early Christians to beware of prophets who ask for money. [3]

Textual and literary analysis

According to modern biblical scholars who support the documentary hypothesis, the account of Balaam in the Book of Numbers is drawn from more than one source, thus explaining the seemingly contradictory attitudes toward him in the text as we have it today. The "J" or "Yahwist" source is more negative toward Balaam, while the "E," or Elohist source, is more positive.

The tale of Balaam's talking donkey, for example, belongs to "J" and is intended to mock the prophet. It shows, first of all, that even Balaam's donkey is more spiritually perceptive than Balaam, for she sees the angel before he does. And secondly, it shows that since God can even make an ass talk, he can easily put words in the mouth of a supposedly great but evil prophet like Balaam. The Elohist version of the story, on the other hand, shows Balaam to be a gifted prophet of real integrity, who takes a great risk it confronting King Balak with blessings for Israel instead of curses and refuses to be bribed into going against the will of "Yahweh my God."

Balaam's prophecies take the form of (Hebrew) poems and cover the following themes:

- The first, Numbers 23:7-10, prophesies the unique exaltation of the Kingdom of Israel, and its countless numbers.

- The second, Numbers 23:18-24, celebrates the moral virtue of Israel, its monarchy, and military conquests.

- The third, Numbers 24:3-9, celebrates the glory and conquests of Israel's monarchy.

- The fourth, Numbers 24:14-19, announces the coming of a king (David) who will conquer Edom and Moab.

- The fifth, Numbers 24:20, concerns the ruination of Amalek.

- The sixth, Numbers 24:21-22, concerns the destruction of the Kenites by Assyria.

- The seventh, Numbers 24:23-24, concerns ships approaching from the west, to attack Assyria and Eber.

While the poems themselves are presented in the context of the Elohist and Yahwist narratives, many scholars consider some of them to pre-date these sources. [4] Some critics also view the Balaam narratives, excepting the episode involving the ass, to be simply a framework invented in order to insert the earlier poems. Scholars debate whether the poems themselves constitute actual prophecies, or prophetic poems created after the events they appear to predict. [5]

Finally, social critics question the moral standards of the biblical account. Balaam had blessed Israel at the risk of his life in front of a powerful Moabite king, but was later killed by the Israelites whom he blessed. Why, after blessing Israel so courageously, would he later seduce the Israelites into worshiping Baal? Even more troubling is the idea of Moses demanding that Midianite women and boys be slaughtered, sparing only virgin girls who were forced into become the "wives" of Israelite soldiers.

Etymology

The etymology of the name Balaam is uncertain. Several sources translate it either "glutton," or "foreigner." The rabbis who take a negative view toward Balaam, playing on the name, call him Belo 'Am, meaning without people, more explicitly meaning that he is "without a share with the people in the world to come," or call him Billa' 'Am, meaning "one that ruined a people." This deconstruction of his name into B‚ÄĒl Am is supported by many modern biblical critics, who consider his name to simply be derived from Baal Am, a reference to Am, one of the gods (ba'alim) of Moab. It should be noted that several important Israelite figures also had names including the syllable "Baal," including Gideon (also called Jerubaal), and King Saul's sons Ish-bosheth and Mephi-bosheth (also called Ishbaal and Meribaal). [6]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Why the angel opposes him when God has ordered him to go is uncertain. One possibility is that this portion of the text, thought to be from the Yahwist source, was originally independent of the Elohist's story of God's commanding Balaam to go to Balak. Elsewhere, in the stories of both Jacob and Moses, the Yahwist portrays God as similarly obstructing His heroes.

- ‚ÜĎ The name of the site is given as Bamoth Baal, meaning high place of Baal. However, the term "Baal" did not necessarily refer to a specific deity. It could means simply "The Lord's high place."

- ‚ÜĎ The Didache, or "Teaching of Twelve," similarly teaches that the way to distinguish a true prophet from a false one is that a true prophet will not ask for money.

- ‚ÜĎ An archaeological discovery in 1967 uncovered references to a Book of Balaam, from which these poems may have originally been taken. (Hoftijzer, 1976.)

- ‚ÜĎ Such debates are common in relation to prophecies predicting specific events that "later" come to pass. The essential question is whether some scribe faithfully recorded an ancient prophecy, or in effect invented the prophecy and placed it in the mouth of an earlier prophet. In Balaam's case, one needs to deal with the question of who might have recorded the prophecy he uttered in the presence of the Moabite king, and how it later came to be recorded in the Hebrew Bible.

- ‚ÜĎ The word Ba'al means simply "Lord" in various semitic languages, including Hebrew.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hoftijzer, Jacob. #page_scan_tab_contents "The Prophet Balaam in a 6th Century Aramaic Inscription." Biblical Archaeologist, 39 (1976).

- McCarter, P. Kyle.#page_scan_tab_contents "The Balaam Texts from Deir AllńĀ: The First Combination." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 239(Summer 1980): 49-60.

- Olrik, Axel. Principles for Oral Narrative Research. Translated by Kirsten Wolf and Jody Jensen. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, (1921) 1992 transl.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.