Great Flood

The story of a Great Flood sent by God or the gods to destroy civilization as an act of divine retribution is a widespread theme among many cultural myths. It is best known from the biblical story of Noah, but there are several other famous versions, such as stories of Matsya in the Hindu Puranas, Deucalion in Greek mythology, and Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Many of the world's cultures past and present have stories of a Great Flood that devastated earlier civilizations. A good deal of similarity exists between several of the flood myths, leading scholars to believe that these have evolved from or influenced each other. Others of these stories seem to be of a more local nature, although nearly all of them involve the survival of only a small number of humans who repopulate humankind.

The scientific community is divided about the historicity of such an event as a Great Flood. Most archaeologists and geologists recognize that there were indeed major floods that devastated substantial civilized areas, but most deny that there was ever a single deluge in the last 6,000 years that covered the whole earth or even a major portion of it.

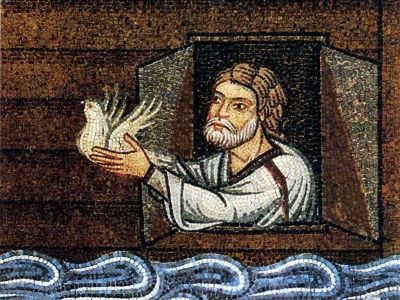

Noah's Flood

Although the story of Noah's flood may not be the most ancient of the flood stories, it is by far the most well known. In the story recorded in the book of Genesis, God is saddened by seeing all the evil which has entered man's heart, and decides to destroy all living things on earth (Genesis 6:5-8). He selects Noah, who alone is "righteous in his generation," and instructs him to build an ark and to preserve two of each creature.[1] Noah builds the ark and God makes it rain for 40 days and 40 nights. After 150 days, the ark comes to rest on the mountain of Ararat. Noah opens a window of the ark and sends forth a raven and a dove. After the earth becomes dry enough, Noah and his family, together with the animals, descend from the ark. Noah offers a sacrifice to God, who accepts his offering and promises: "never again will I destroy all living creatures." (Gen 8:21) God blesses Noah to "be fruitful and multiply" and places a rainbow in the sky as a sign of His covenant with Noah and his descendants. Noah then plants a vineyard and becomes drunk with wine. He falls asleep naked, and ends up cursing his grandson, Canaan, to be a slave to his brothers after Canaan's father, Ham, finds Noah sleeping naked in his tent, Ham ashamed of his father's nakedness, informs his brothers of this.

Non-Biblical: The second century B.C.E. 1st Book of Enoch is an apocryphal addition to the Hebrew flood legend, the cause of the evil mentioned in Gen. 6 is linked specifically to the Nephilim, the evil race of giants who are the titanic children of the angelic "sons of God" and human females. Enoch 9:9 explains that, as a result of these unnatural unions, "the women bore giants, and thereby the whole Earth has been filled with blood and iniquity." The Nephilim are also mentioned in Genesis 6, but in much less detail.

Ancient Near East

Sumerian

The Sumerian myth of Ziusudra tells how the god Enki warns Ziusudra, king of Shuruppak, of the gods' decision to destroy mankind in a flood. The passage describing why the gods have decided this is unfortunately lost. Enki instructs Ziusudra to build a large boat. After a flood of seven days, Ziusudra opens the boat's window and then offers sacrifices and prostrations to An (the sky-god) and Enlil (the chief of the gods). He is rewarded by being given eternal life in Dilmun (the Sumerian Eden).

The myth of Ziusudra exists in a single copy, the fragmentary Eridu Genesis, datable by its script to the seventeenth century B.C.E.[2]

The Sumerian king list, a genealogy of historical, legendary, and mythological Sumerian kings, also mentions a Great Flood.

Babylonian (Epic of Gilgamesh)

In the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh the story of the Flood is told in some detail, with many striking parallels to the Genesis version. The hero, Gilgamesh, seeking immortality, searches out the human immortal Utnapishtim in Dilmun, a kind of terrestrial paradise.

Utnapishtim tells how Ea (the Babylonian equivalent of the Sumerian Enki) warned him of the gods' plan to destroy all life through a Great Flood and instructed him to build a vessel in which he could save his family, his friends and servants, his cattle, and other wealth. The deluge comes and covers the earth. As in the Genesis version, Untapishtim sends out both a dove and raven from his boat before descending on dry land. After the Deluge, he offers a sacrifice to the gods, who repented their action and make Utnapishtim immortal.

Akkadian (Atrahasis Epic)

The Babylonian Atrahasis Epic (written no later than 1700 B.C.E., the name Atrahasis means "exceedingly wise"), gives human overpopulation as the cause for the great flood. After 1200 years of human fertility, the god Enlil feels disturbed in his sleep due to the noise and commotion caused by the growing population of mankind. He turns for help to the divine assembly who send a plague, then a drought, a famine, and then saline soil, all in an attempt to reduce the numbers of mankind. All these temporary measures prove ineffective as, 1200 years after each solution, the original problem returns. When the gods decide on a final solution, to send a flood, the god Enki, who has a moral objection to this solution, discloses the plan to Atrahasis, who then builds a survival vessel according to divinely given measurements.

To prevent the other gods from bringing another such harsh calamity, Enki creates new solutions in the form of social phenomena such as non-marrying women, barrenness, miscarriages and infant mortality, in order to help keep the population from growing out of control.

Asia-Pacific

China

The ancient Chinese civilization was concentrated at the bank of Yellow River near present day Xian. It was believed that the severe flooding along the river bank was caused by dragons (representing gods) living in the river who were being angered by the mistakes of the people. There are many sources of flood myths in ancient Chinese literature. Some appear to refer to a worldwide deluge.

The text of Shiji, Chuci, Liezi, Huainanzi, Shuowen Jiezi, Siku Quanshu, Songsi Dashu, and others, as well as many folk myths, all contain references to a personage named Nüwa. Despite the similarity of her name to the biblical Noah, Nüwa is generally represented as a female who repairs the broken heavens after a great flood or other calamity, and repopulates the world with people. There are many versions of this myth.

Shujing, or "Book of History," probably written around 700 B.C.E. or earlier, describes a situation in its opening chapters in which Emperor Yao is facing the problem of flood waters that reach to the Heavens. This is the backdrop for the intervention of the hero Da Yu, who succeeds in controlling the floods. He goes on to found the first Chinese dynasty.

Shanhaijing, the "Classic of the Mountain & Seas," ends with a similar story of Da Yu spending ten years to control a deluge whose "floodwaters overflowed [to] heaven."

Andaman Islands

In myths of the aboriginal tribes inhabiting the Andaman Islands, the story goes that people became remiss in their duty to obey the commands given to them at the creation. Puluga, the creator god, ceased to visit them and then without further warning sent a devastating flood.

Only four people survived this flood: two men, Loralola and Poilola, and two women, Kalola and Rimalola. When they finally landed they found they had lost their fire, and all living things had perished. Puluga then recreated the animals and plants but does not seem to have given any further instructions, nor did he return the fire to the survivors until tricked into doing so by one of the survivors' recently-drowned friends who reappeared in the form of a kingfisher.[3]

India

The Hindu version of Noah is named Manu. He is warned by an incarnation of Vishnu of the impending Great Flood, enabling him to build a boat and survive to repopulate the earth.

According to the texts Matsya Purana and Shatapatha Brahmana (I-8, 1-6), Manu was a minister to the king of pre-ancient Dravida. He was washing his hands in a river when a little fish swam into his hands and begged him to save its life. He put the fish in a jar, which it soon outgrew. He successively moved it to a tank, a river and then the ocean. The fish then warned him that a deluge would occur in a week that would destroy all life. It turned out that fish was none other than Matsya (Fish in Sanskrit) the first Avatara of Vishnu.

Manu therefore built a boat which Matsya towed to a mountaintop when the flood came, and thus he survived along with some "seeds of life" to re-establish life on earth.

Indonesia

In Batak traditions, the earth rests on a giant snake, Naga-Padoha. One day, the snake tired of its burden and shook the Earth off into the sea. However, the god Batara-Guru saved his daughter by sending a mountain into the sea, and the entire human race descended from her. The Earth was later placed back onto the head of the snake.

Polynesia

Several flood stories are recorded among the Polynesians. However, none of them approach the scale of the Biblical flood.

The people of Ra'iatea tell of two friends, Te-aho-aroa and Ro'o, who went fishing and accidentally awoke the ocean god Ruahatu with their fish hooks. Angered, he vowed to sink Ra'iatea below the sea. Te-aho-aroa and Ro'o begged for forgiveness, and Ruahatu warned them that they could escape only by bringing their families to the islet of Toamarama. These set sail, and during the night, Ra'iatea slipped under the ocean, only to rise again the next morning. Nothing survived except for these families, who erected sacred marae (temples) dedicated to Ruahatu.

A similar legend is found on Tahiti. No reason for the tragedy is given, but the whole island sinks beneath the sea except for Mount Pitohiti. One human couple managed to flee there with their animals and survived.

In Hawaii, a human couple, Nu'u and Lili-noe, survived a flood on top of Mauna Kea on the Big Island. Nu'u made sacrifices to the moon, to whom he mistakenly attributed his safety. Kāne, the creator god, descended to earth on a rainbow, explained Nu'u's mistake, and accepted his sacrifice.

In the Marquesas, the great war god Tu was angered by critical remarks made by his sister Hii-hia. His tears tore through heaven's floor to the world below and created a torrent of rain carrying away everything in its path. Only six people survived.

Australia and New Zealand

According to the Australian aborigines, in the Dreamtime a huge frog drank all the water in the world and a drought swept across the land. The only way to finish the drought was to make the frog laugh. Animals from all over Australia gathered together and one by one attempted to make the frog laugh. When finally the eel succeeded, the frog opened his sleepy eyes, his big body quivered, his face relaxed, and, at last, he burst into a laugh that sounded like rolling thunder. The water poured from his mouth in a flood. It filled the deepest rivers and covered the land. Only the highest mountain peaks were visible, like islands in the sea. Many men and animals were drowned. The pelican who was blackfellow at that time painted himself with white clay and was then swimming from island to island in a great canoe, rescuing other blackfellows. Since that time pelicans have been black and white in remembrance of the Great Flood.[4]

In a tradition of the Ngāti Porou, a Māori tribe of the east coast of New Zealand's North Island, Ruatapu, the child of the great chief Uenuku, became angry when Uenuku demoted Ruatapu for using the sacred comb of Kahutia-te-rangi, the king's younger son. Ruatapu lured Kahutia-te-rangi and a large number of young men of high birth into his canoe, and took them out to sea and drowned them all but Kahutia-te-rangi. Ruatapu convinced the gods of the tides to destroy the land and its inhabitants. As he struggled for his life, Kahutia-te-rangi recited an incantation invoking the southern humpback whales (paikea in Māori) to carry him ashore. Accordingly, he was renamed Paikea, and was the only survivor of the flood.

European Floods stories

Greek

Greek mythology knows three floods. The flood of Ogyges, the flood of Deucalion and the flood of Dardanus, two of which ended two Ages of Man: the Ogygian deluge ended the Silver Age, and the flood of Deucalion ended the First Bronze Age.

- Ogyges. The Ogygian flood is so called because it occurred in the time of Ogyges,[5] a mythical king of Attica. The name Ogyges is synonymous with "primeval" or "earliest dawn." He was the mythical founder and king of Thebes. The Ogygian flood covered the whole world and was so devastating that the country remained without kings until the reign of Cecrops, 1556-1506 B.C.E.[6]Plato in his Laws, Book III, estimates that this flood occurred 10,000 years before his time. Also in Timaeus (22) and in Critias (111-112) Plato describes the "great deluge of all" during the tenth millennium B.C.E.

- Deucalion. The Deucalion legend, as told by Apollodorus in The Library has some similarity to Noah's flood, and the name Deucalion is related to wine, of which the biblical Noah was the inventor. When the anger of Zeus was ignited against the hubris of the Pelasgians, Zeus decided to put an end to the First Bronze Age with the Deluge. Prometheus advised his son Deucalion to build a chest or ark to save himself, and other men perished except for a few who escaped to high mountains. The mountains in Thessaly were parted, and all the world beyond the Isthmus and Peloponnese was overwhelmed. Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha, after floating in a chest for nine days and nights, landed on Parnassus. An older version of the story told by Hellanicus has Deucalion's "ark" landing on Mount Othrys in Thessaly. Another account has him landing on a peak, probably Phouka, in Argolis, later called Nemea. When the rains ceased, he sacrificed to Zeus. Then, at the bidding of Zeus, he threw stones behind him, and they became men. His wife Pyrrha, who was the daughter of Epimetheus and Pandora, also threw stones, and these became women.

- Dardanus. According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Dardanus, a son of Zeus and Electra, left Pheneus in Arcadia to colonize a land in the northeast Aegean Sea. When the deluge occurred, the land was flooded, and the mountain on which he and his family survived formed the island of Samothrace. Dardanus left Samothrace on an inflated skin to the opposite shores of Asia Minor and settled at the foot of Mount Ida. Due to fear of another flood he did not build a city, but lived in the open for 50 years. His grandson Tros eventually built a city, which was named Troy after him.

Germanic

In Norse mythology, the giant Bergelmir was a son of Thrudgelmir and the grandson of Aurgelmir, the founder of the race of frost giants. Bergelmir and his wife were the only frost giants to survive the deluge of Aurgelmir's blood, when Odin and his brothers butchered him. The giant couple survived by crawling into a hollow tree trunk, and then founded a new race of frost giants.

Irish

According to the mythical history of Ireland, the first inhabitants of Ireland were led there by Noah's granddaughter Cessair. In one version of the story, when her father was denied a place in the ark by Noah, Cessair advised him to build an idol. This idol advised them that they could escape the Deluge in a ship. Cessair, along with three men and 50 women, set off and sailed for more than seven years. They landed in Ireland at Donemark, on Bantry Bay in County Cork, just 40 days before the Flood.

The three men shared the women as wives between them. Six days before the Flood, Cessair died of a broken heart at Cuil Ceasrach in Connacht. The rest of Cessair's people were wiped out in the Flood, with the exception of one of the males, Fintan, who turned into a salmon. After a series of animal transformations he eventually became a man again and told his people's story.

Americas

Aztec

There are several variants of the Aztec Flood story. One of the more famous is that of Nota, the Aztec version of Noah. However, this story is controversial for several reasons, especially because it was recorded by Spanish scribes well after Christian culture had a chance to interact with Aztec civilization.

- When the Sun Age came, there had passed 400 years. Then came 200 years, then 76. Then all mankind was lost and drowned and turned to fishes. The water and the sky drew near each other. In a single day all was lost. But before the Flood began, Titlachahuan had warned the man Nota and his wife Nena, saying, 'Make no more pulque, but hollow a great cypress, into which you shall enter the month Tozoztli. The waters shall near the sky.' They entered, and when Titlachahuan had shut them in he said to the man, 'Thou shalt eat but a single ear of maize, and thy wife but one also'. And when they had each eaten one ear of maize, they prepared to go forth, for the water was tranquil.

- — Ancient Aztec document Codex Chimalpopoca, translated by Abbé Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg.

Inca

In Inca mythology, the god Viracocha, the creator of civilization, destroyed the giants, as well as the other inhabitants around Lake Titicaca with a Great Flood, and two people repopulated the earth. They survived in sealed caves.

Maya

In Maya mythology, from the Popol Vuh, Part 1, Chapter 3, Huracan ("one-legged") was a wind and storm god. It is from his name that the English word hurricane is derived. Huracan caused the Great Flood (of resin) after the first humans angered the gods because, being made of wood, they were unable to engage in worship. Huracan lived in the windy mists above the floodwaters and spoke "earth" until land came up again from the seas. Humans had become monkeys, but later, real people would emerge, and three men and four women repopulate the world after the flood.

Hopi

In Hopi mythology, most people moved away from the ways of the creator god, Sotuknang, and he destroyed the world first by fire and then by cold, recreating it both times for the people that still followed the laws of creation, who survived by hiding underground. People became corrupt and warlike a third time. As a result, Sotuknang guided the people to Spider Woman, his helper in the creation process, and she cut down giant reeds and sheltered the people in the hollow stems. Sotuknang then caused a Great Flood, and the people floated atop the water in their reeds. The reeds came to rest on a small piece of land, and the people emerged, with as much food as they started with. The people traveled on in their canoes, guided by their inner wisdom (which is said to come from Sotuknang through the door at the top of their head). They traveled to the northeast, passing progressively larger islands, until they came to the Fourth World, a great land mass. The islands then sank into the ocean.

Caddo

In Caddo mythology, four monsters grew in size and power until they touched the sky. At that time, a man heard a voice telling him to plant a hollow reed. He did so, and the reed grew very big very quickly. The man entered the reed with his wife and pairs of all good animals. Waters rose and covered everything but the top of the reed and the heads of the monsters. A turtle then killed the monsters by digging under them and uprooting them. The waters subsided and winds dried the earth.

Menominee

In Menominee mythology, Manabus, the trickster, "fired by his lust for revenge" shot two underground gods when they and the other gods were at play. When they all dived into the water, a huge flood arose. "The water rose up …. It knew very well where Manabus had gone." He runs, but the water, coming from Lake Michigan, chases him faster and faster, even as he runs up a mountain and climbs to the top of the lofty pine at its peak. Four times he begs the tree to grow just a little more, and four times it obliges until it can grow no more. But the water keeps climbing "up, up, right to his chin, and there it stopped." There was nothing but water stretching out to the horizon. And then Manabus, helped by the diving animals and the Muskrat, created the world as we know it today.

Theories of origin

Many orthodox Jews, and Christians, believe that the flood happened as recorded in Genesis. It is often argued that the large number of flood myths in other cultures suggests that they originated from a common, historical event, of which Genesis is the accurate and true account. The myths from various cultures, often cast in polytheistic contexts, are thus corrupted memories of an historical global Deluge.

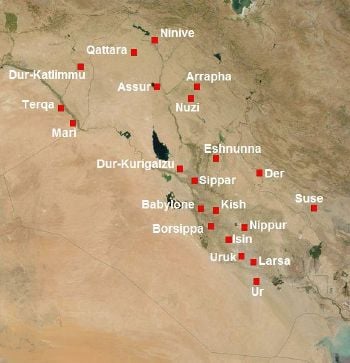

In the early days of Biblical archeology, prominent academics believed they had discovered evidence for a historical worldwide flood,[7] but this view has been largely abandoned. Instead, it is generally agreed that devastating local floods, covering large flat areas such as those between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, could easily have given rise to the stories of Ziusudra, Atrahasis, Utnapishtim, and Noah.[8] Excavations in Iraq have shown evidence of a major flood at Shuruppak about 2,900-2,750 B.C.E., which extended nearly as far as the city of Kish, whose king Etana, supposedly founded the first Sumerian dynasty after the flood. "Flood geology" is propounded by biblically-oriented scientists who have tried to support the Great Flood theory scientifically, but this is not accepted by the majority of geologists, both Christian and non-Christian, who consider it a form of pseudoscience.[9]

Among other theories concerning the origins of the legends of a Great Flood, there has been speculation that a large tsunami in the Mediterranean Sea caused, by the huge eruption of the volcano Thera, ca. 1630-1500 B.C.E., was the historical basis for folklore that evolved into the Deucalion myth. Some have also suggested that flood myths could have arisen from folk stories related to the huge rise in sea levels that accompanied the end of the last Ice Age some 10,000 years ago, passed down the generations as an oral history.

In 1998 William Ryan and Walter Pitman, geologists from Columbia University, published evidence that a massive flood of waters from the Mediterranean Sea through the Bosporus occurred about 5600 B.C.E., resulting in widespread destruction of major population centers around the Black Sea. It is suggested that this would have naturally resulted in various Great Flood myths as major cities would have been lost to these waters.

Notes

- ↑ Or seven pairs if they are "clean") animals, according to Genesis 7:2.

- ↑ The Deluge Sacred Texts. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ↑ A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, The Andaman Islanders (Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1922), ISBN 1015726380).

- ↑ Myths and Legends of the Australian Aborigines - A Legend of the Great Flood Sacred Texts. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ↑ William Smith (ed.), Ogy'gus A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ↑ Theodor Gaster, Myth, Legend, and Custom in the Old Testament (Harper Collins, 1969, ISBN 978-0061386404).

- ↑ William F. Albright, Archeology and the Religion of Israel (Westminster John Knox Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0664227425), 176.

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer, The Sumerians: Their history, culture and character (University of Chicago, 1971, ISBN 978-0226452388).

- ↑ Ian Plimer, Telling Lies for God: Reason versus creationism (Random House, 1994, ISBN 978-0091828523).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Albright, William F. Archeology and the Religion of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0664227425

- Alexander, Eliot, and Joseph Campbell. The Universal Myths: Heroes, Gods, Tricksters, and Others. Plume, 1990. ISBN 978-0452010277

- Bailey Lloyd R. Noah, the Person and the Story. University of South Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0872496376

- Best, Robert M. Noah's Ark and the Ziusudra Epic. Enlil Press, 1999. ISBN 0966784014

- Brinton, Daniel. The Myths Of The Creation, The Deluge, The Epochs Of Nature And The Last Day. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2005. ISBN 978-1425373351

- Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It? What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel? Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2001. ISBN 978-0802821263

- Dundes, Alan (ed.). The Flood Myth. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. ISBN 0520059735

- Gaster, Theodor H. Myth, Legend, and Custom in the Old Testament. Harper Collins, 1969. ISBN 978-0061386404

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. The Sumerians: Their history, culture and character. University of Chicago, new ed., 1971. ISBN 978-0226452388

- Lambert W.G., and Millard A.R. Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood. Eisenbrauns, 1999. ISBN 1575060396

- Lewis, Mark Edward. The Flood Myths of Early China. State University of New York Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0791466643

- Plimer, Ian. Telling Lies for God: Reason versus creationism. Random House, 1994. ISBN 978-0091828523

- Radcliffe-Brown, A.R. The Andaman Islanders. Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1922). ISBN 1015726380

- Ryan, William and Walter Pitman. Noah's Flood: The New Scientific Discoveries About The Event That Changed History. Simon & Schuster; Touchstone edition, 2000. ISBN 978-0684859200

External links

All links retrieved May 24, 2024.

- Flood Legends from Around the World NW Creation Network.

- Scientific Evidence for the Many Myths of the Great Flood Ancient Origins

- Evidence for a Flood Smithsonian Magazine

- Story of the Flood The Chickasaw Nation

- A Flood of Myths and Stories PBS

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.