Bamana Empire

The Bamana Empire (also Bambara Empire or Ségou Empire) was a large pre-colonial West African state based at Ségou, now in Mali. It was ruled by the Kulubali or Coulibaly dynasty established circa 1640 by Fa Sine also known as Biton-si-u. The empire existed as a centralized state from 1712 to the 1861 invasion of the Fulani jihadist Toucouleur conqueror El Hadj Umar Tall. The Troucoulier Empire, with Bambara help, fell to the French in 1890. Had the empire not fallen to the jihadists, it would almost certainly have to the French or the British, since the only African polity to survive European colonialism was the Ethiopian Empire and even Ethiopia was occupied by Italy under Benito Mussolini from 1935 to 1941. On the one hand, few may mourn the end of an empire that thrived on the slave trade. On the other hand, it was European participation in that trade at the time that made it as profitable as it was. Too often, Africa is regarded as having had no real history in terms of states and empires and civilizations (with the exception of Egypt which often is regarded as somehow ânot of Africaâ) before the European arrived to fill out its otherwise empty space. In fact, empires and kingdoms are rife throughout Africaâs history. Some were less moral than others. Some thrived on war. Some thrived on commerce and trade and lived peacefully with their neighbors. The story of Africa, like that of the human race, is a mixture of what can be celebrated and of what can be regarded as a lesson in how we should not live our lives.

The Kulubali Dynasty

In around 1640, Fa Sine became the third Faama (Mande word for King) of a small kingdom of Bambara people in the city of Ségou in Mali. Though he made many successful conquests of neighboring tribes and kingdoms, he failed to set up significant administrative framework, and the new kingdom disintegrated following his death (c. 1660). In the early eighteenth century, Mamari Kulubali (sometimes cited as Mamari Bitòn) settled in Ségou and joined an egalitarian youth organization known as a tòn. Mamari soon reorganized the tòn as a personal army, assumed the title of bitòn, and set about subduing rival chiefs. He established control over Ségou, making it the capital of a new Bambara Empire.

Fortifying the capital with Songhai techniques, Bitòn Kulubali built an army of several thousand men and a navy of war canoes to patrol the Niger. He then proceeded to launch successful assaults against his neighbors, the Fulani, the Soninke, and the Mossi. He also attacked Tomboctou, though he held the city only briefly. During this time he founded the city of Bla as an outpost and armory. Mamari Kulubali was the last ruler to be called Bitòn. All future rulers were simply titled Faama. Bakari, the first Faama after Mamari reigned from (1710-1711). Faama De-Koro ascended in 1712 reigning until 1736. The kingdom had three more faamas with unstable four-year reigns until falling into anarchy in 1748.

The Ngolosi

In 1750, a freed slave named Ngolo Diarra seized the throne and re-established stability, reigning for nearly forty years of relative prosperity. The Ngolosi, his descendants, would continue to rule the Empire until its fall. Ngolo's son Mansong Diarra took the throne following his father's 1787 death and began a series of successful conquests, including that of Tomboctou (c. 1800) and the Massina region.

Economy and structure

The Bambara Empire was structured around traditional Bambara institutions, including the kòmò, a body to resolve theological concerns. The kòmò often consulted religious sculptures in their decisions, particularly the four state boliw, large altars designed to aid the acquisition of political power.

The economy of the Bambara Empire flourished through trade, especially in slaves captured in their many wars. The demand for slaves then led to further fighting, leaving the Bambara in a perpetual state of war with their neighbors.

Mungo Park, passing through the Bambara capital of Ségou two years after Diarra's 1795 death, recorded a testament to the Empire's prosperity:

- The view of this extensive city, the numerous canoes on the river, the crowded population, and the cultivated state of the surrounding countryside, formed altogether a prospect of civilization and magnificence that I little expected to find in the bosom of Africa.[1]

Jihad and fall

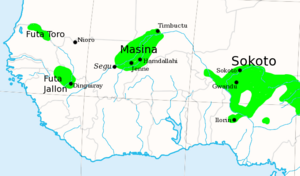

At the Battle of Noukouma in 1818, Bambara forces met and were defeated by Fula Muslim fighters rallied by the jihad of Cheikou Amadu (or Seku Amadu) of Massina. The Bambara Empire survived but was irreversibly weakened. Seku Amadu's forces decisively defeated the Bambara, taking Djenné and much of the territory around Mopti and forming into a Massina Empire. Timbuktu would fall as well in 1845. This was one of the jihads inspired by the founder of the Sokoto Empire, Usman dan Fodio. By the mid-nineteenth century, a series of jihadist emirates stretched across West Africa.

The real end of the empire, however, came at the hands of El Hadj Umar Tall, a Toucouleur conqueror who swept across West Africa from Dinguiraye. Umar Tall's mujahideen readily defeated the Bambara, seizing Ségou itself on March 10, 1861, forcing the population to convert to Islam, and declaring an end to the Bambara Empire (which effectively became part of the Toucouleur Empire). Born Umar bin-Said in Halwar, Futa Tooro (in present-day Senegal), Umar Tall attended a madrassa in his youth before embarking on the Hajj in 1820. After many years of scholarship, in 1826 Umar Tall returned with his new title of "El Hadj" to assume the caliphate of the Tijaniyya brotherhood for the Sudan (also know as non-Arab Africa). Settling in Sokoto, he took several wives, one of whom was a daughter of Fulani Sultan Muhammed Bello. In 1836, El Hajj Umar Tall moved to Fouta Djallon and ultimately to Dinguiraye (in present-day Guinea) where he began preparations for his jihad.

Initial conquests

In 1848, El Hajj Umar Tall's Toucouleur army, equipped with European light arms, invaded several neighboring, non-Muslim, Malinké regions and met with immediate success. Umar Tall pressed on into what is today the region of Kayes in Mali, conquering a number of cities and building a tata (fortification) near the city of Kayes that is today a popular tourist destination.

In April of 1857, Umar Tall declared war on the Khasso kingdom and besieged the French colonial army at Medina Fort. The siege failed on July 18 of the same year when Louis Faidherbe, French governor of Senegal, arrived with relief forces.

Conqueror of the Bambara

After his failure to defeat the French, El Hadj Umar Tall launched a series of assaults on the Bambara kingdoms of Kaarta and Ségou. The Kaarta capital of Nioro du Sahel fell quickly to Umar Tall's mujahideen, followed by Ségou on March 10, 1861. While Umar Tall's wars thus far had been against the animist Bambara or the Christian French, he now turned his attention to the smaller Islamic states of the region. Installing his son Ahmadu Tall as imam of Ségou, Umar Tall marched down the Niger, on the Massina imamate of Hamdullahi. More than 70,000 died in the three battles that followed until the final fall and destruction of Hamdullahi on March 16, 1862. Now controlling the entire Middle Niger, Umar Tall moved against Timbuktu, only to be repulsed in 1863 by combined forces of the Tuaregs, Moors, and Fulani tribes. Meanwhile, a rebellion broke out in Hamdullahi under Balobo, brother of executed Massina monarch Amadu; in 1864, Balobo's combined force of Peuls and Kountas drove Umar Tall's army from the city and into Bandiagara, where Umar Tall died in an explosion of his gunpowder reserves on February 12. His nephew Tidiani Tall succeeded him as the Toucouleur emperor, though his son Ahmadu Seku did much of the work to keep the empire intact from Ségou.

Revenge of the Banara

In 1890, the French, allied with the Bambara, who perhaps wanted revenge for their earlier defeat, entered Ségou, and captured the city. Ahmadu fled to Sokoto in present-day Nigeria, marking the effective end of the empire.

Notes

- â Davidson, 1995, p. 245.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Condé, Maryse. Segu. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1996. ISBN 978-0140259490

- Davidson, Basil. Africa in History. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 978-0684826677

- Djata, Sundiata A. K. The Bamana Empire by the Niger: Kingdom, Jihad and Colonization 1712-1920. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1997. ISBN 1558761314

- Hanson, John H. Migration, Jihad, and Muslim authority in West Africa: the Futanke colonies in Karta. Bloomington, IL: Indiana University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0253330888

- Robinson, David. The Holy War of Umar Tal: the Western Sudan in the mid-nineteenth century. Oxford studies in African affairs. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0198227205

- Willis, John Ralph. In the path of Allah: the passion of al-Hajj ʻUmar: an essay into the nature of charisma in Islam. London, UK: F. Cass, 1989. ISBN 978-0714632520

External links

All links retrieved September 17, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.