Battle of Aegospotami

| Battle of Aegospotami | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peloponnesian War | |||||||

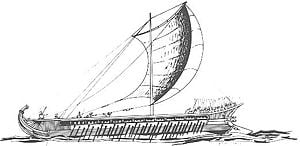

A Greek trireme | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Sparta | Athens | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Lysander | 6 generals | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | 170 ships | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| Minimal | 160 Ships, Thousands of sailors | ||||||

The naval Battle of Aegospotami took place in 404 B.C.E. and was the last major battle of the Peloponnesian War. In the battle, a Spartan fleet under Lysander completely destroyed the Athenian navy. This effectively ended the war, since Athens could not import grain or communicate with its empire without control of the sea. Athen's defeat resulted in the establishment of a Spartan-sponsored oligarchic government known as the rule of the Thirty Tyrants, temporarily ending Athenian democracy. Democracy, however, was soon restored (403) and continued until Philip II of Macedonia conquered Athens in 338 B.C.E. His son, Alexander the Great, expanded his Empire so extensively that the city-state system itself was no longer viable. However, it would be Athenian culture, with its love of art and learning and preference for negotiation, dialogue and diplomacy—not totalitarian, militant Spartan culture—that Alexander would choose to spread throughout his Empire, and which would continue to influence the Roman world. The Battle of Aegospotami saw victory of a culture that in many respects represented a war machine. Ultimately, however, it was the humanitarian culture of Athens and not the military culture of Sparta that became synonymous with classical culture, and lived to inform the thinking of the European Renaissance and Enlightenment.

| Peloponnesian War |

|---|

| Sybota – Potidaea – Chalcis – Rhium – Naupactus – Mytilene – Tanagra – Aetolia – Olpae – Pylos – Sphacteria – Delium – Amphipolis – Mantinea – Sicilian Expedition – Syme – Cynossema – Abydos – Cyzicus – Notium – Arginusae – Aegospotami |

Prelude

Lysander's campaigns

In 405 B.C.E., following the severe Spartan defeat at the Battle of Arginusae, Lysander, the commander who had been responsible for the first Spartan naval successes, was reinstated in command.[1] Since the Spartan constitution prohibited any commander from holding the office of navarch more than once, he was appointed as a vice-admiral instead, with the clear understanding that this was a mere legal fiction.[2]

One of Lysander's advantages as a commander was his close relationship with the Persian prince Cyrus. Using this connection, he quickly raised the money to begin rebuilding the Spartan fleet.[3] When Cyrus was recalled to Susa by his father Darius, he took the unorthodox step of appointing Lysander as satrap of Asia Minor.[4] With the resources of this entire wealthy Persian province at his disposal, Lysander was able to quickly reconstitute his fleet.

He then set off on a series of campaigns throughout the Aegean.[5] He seized several Athenian-held cities, and attacked numerous islands. He was unable to move north to the Hellespont, however, because of the threat from the Athenian fleet at Samos. To divert the Athenians, Lysander struck westward. Approaching quite near to Athens itself, he attacked Aegina and Salamis, and even landed in Attica. The Athenian fleet set out in pursuit, but Lysander sailed around them, reached the Hellespont, and established a base at Abydos. From there, he seized the strategically important town of Lampsacus. From here, the way was open to enter the Bosporus and close down the trade routes from which Athens received the majority of her grain. If the Athenians were going to avoid starvation, Lysander needed to be contained immediately.

Athenian response

The Athenian fleet caught up with Lysander shortly after he had taken Lampsacus, and established a base at Sestos. However, perhaps because of the need to keep a close watch on Lysander, they set up camp on a beach much nearer to Lampsacus. The location was less than ideal because of the lack of a harbor and the difficulty of supplying the fleet, but proximity seems to have been the primary concern in the minds of the Athenian generals.[6] Every day, the fleet sailed out to Lampsacus in battle formation, and waited outside the harbor; when Lysander refused to emerge, they returned home.[7]

Alcibiades's involvement

At this time, the exiled Athenian leader Alcibiades was living in a castle quite near the Athenian camp. Coming down to the beach where the ships were gathered, he made several suggestions to the generals. First, he proposed relocating the fleet to the more secure base at Sestos. Second, he claimed that several Thracian kings had offered to provide him with an army. If the generals would offer him a share of the command, he claimed that he would use this army to assist the Athenians. The generals, however, declined this offer and rejected his advice, and Alcibiades returned home.[8]

The battle

Two accounts of the battle of Aegospotami exist. Diodorus Siculus relates that the Athenian general in command on the fifth day at Sestos, Philocles, sailed out with thirty ships, ordering the rest to follow him.[9] Donald Kagan has argued that the Athenian strategy, if this account is accurate, must have been to draw the Peloponnesians into an attack on the small force so that the larger force following could surprise them.[10] In the event, the small force was immediately defeated, and the remainder of the fleet was caught unprepared on the beach.

Xenophon, on the other hand, relates that the entire Athenian fleet came out as usual on the day of the battle, and Lysander remained in the harbor. When the Athenians returned to their camp, the sailors scattered to forage for food; Lysander's fleet then sailed across from Abydos, and captured most of the ships on the beach, with no sea fighting at all.[11]

Whichever account of the battle itself is accurate, the result is clear. The Athenian fleet was obliterated; only nine ships escaped, led by the general Conon. Lysander captured nearly all of the remainder, along with some three or four thousand Athenian sailors. Of the escaped ships, the messenger ship Paralus was dispatched to inform Athens of the disaster. The rest, with Conon, sought refuge with a friendly ruler in Cyprus.

Aftermath

Lysander and his victorious fleet sailed back to Abydos. There, the thousands of Athenian prisoners (who composed approximately one-tenth of all Athenian forces)[12] were executed. He then began moving slowly towards Athens, capturing cities along the way. The Athenians, with no fleet, were powerless to oppose him. Only at Samos did Lysander meet resistance; the democratic government there, fiercely loyal to Athens, refused to give in, and Lysander left a besieging force behind him.

Xenophon reports that when the news of the defeat reached Athens,

…a sound of wailing ran from Piraeus through the long walls to the city, one man passing on the news to another; and during that night no one slept, all mourning, not for the lost alone, but far more for their own selves.[13]

Fearing the retribution that the victorious Spartans might take on them, the Athenians resolved to hold out, but their cause was hopeless. After a siege, the city surrendered in March 404 B.C.E. The walls of the city were demolished, and a pro-Spartan oligarchic government was established (the so called Thirty Tyrants' regime). The Spartan victory at Aegospotami marked the end of 27 years of war, and placed Sparta in a position of complete dominance throughout the Greek world and established a political order that would last for more than thirty years.

Notes

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenica, trans. H. G. Dakyns (New York: Macmillan and Co., 1897).

- ↑ Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 469.

- ↑ Xenophon, 2.1.11-12.

- ↑ Xenophon, 2.1.14.

- ↑ Xenophon, 2.1.15-19.

- ↑ Kagan, 473.

- ↑ Xenophon, 2.1.23.

- ↑ Xenophon, 2.1.25-26.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: Library of History, vol. 5, Books 12.41-13, trans. C. H. Oldfather (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1946).

- ↑ Kagan, 471-78.

- ↑ Xenophon, 2.2.1.

- ↑ Kagan, 476.

- ↑ Xenophon, 2.2.3.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dakyns, H. G., trans. Xenophon. New York: Macmillan and Co., 1897.

- Fuller, J.F.C. From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Lepanto. Vol.1, A Military History of the Western World. Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 1987.

- Kagan, Donald. The Peloponnesian War. New York: Penguin Books, 2003. ISBN 0670032115

- Montagu, John Drogo. Battles of the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Chronological Compendium of 667 Battles to 31 B.C.E., From the Historians of the Ancient World. London: Greenhill Books, 2000. ISBN 1853673897

- Siculus, Diodorus. Diodorus Siculus: Library of History. Vol. 5, Books 12.41-13. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1946. ISBN 0674994221

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.