Battle of Agincourt

| Battle of Agincourt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of Agincourt, fifteenth century miniature | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Kingdom of England | Kingdom of France | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Henry V of England | Charles d'Albret | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| About 6,000 (but see Modern re-assessment). 5/6 longbowmen, 1/6 dismounted men-at-arms. | Between 20,000 and 30,000 (but see Modern re-assessment). Estimated to be 1/6 crossbowmen and archers, 1/2 dismounted men-at-arms, 1/3 mounted knights. | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 100-250 Casualties | Around 6,000 | ||||||

The Battle of Agincourt (IPA pronunciation: [/ÉËÊÉȘn'kuËÊ/]) was fought on October 25, 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day), in northern France as part of the Hundred Years' War. Immortalized by William Shakespeare's play, Henry V, Agincourt is remembered as an iconic moment in British history. Its memory has often been evoked to raise morale and to stir patriotic loyalty in the face of great odds.

The armies involved were those of the English King Henry V and Charles VI of France. Charles did not command his army himself, as he was incapacitated. The French were commanded by the Constable Charles d'Albret and various prominent French noblemen of the Armagnac party. The battle is notable for the use of the English longbow, which the English used in very large numbers, with long bowmen forming the vast majority of their army.

| Hundred Years' War |

|---|

| Edwardian â Breton Succession â Castilian â Two Peters â Caroline â Lancastrian |

| Hundred Years' War (1415-1453) |

|---|

| Agincourt â Rouen â BaugĂ© â Meaux â Cravant â Verneuil â OrlĂ©ans â Jargeau â Meung-sur-Loire â Beaugency â Patay â CompiĂšgne â Gerbevoy â Formigny â Castillon |

Henry V invaded France for several reasons. He hoped that by fighting a popular foreign war, he would strengthen his position at home. He wanted to improve his finances by gaining revenue-producing lands. He also wanted to take nobles prisoner either for ransom or to extort money from the French king in exchange for their return. Evidence also suggests that several lords in the region of Normandy promised Henry their lands when they died, but the King of France confiscated those lands instead.

The campaign

The English army landed in northern France on August 13, 1415, and besieged the port of Harfleur with an army of about 12,000. The siege took longer than expected. The town surrendered on September 22, and the English army did not leave until October 8. The campaign season was coming to an end, and the English army had suffered many casualties through disease. Henry decided to move most of his army (roughly 7,000) to the port of Calais, the only English stronghold in northern France, where they could re-equip over the winter.

During the siege, the French had been able to call up a large feudal army, which d'Albret deployed between Harfleur and Calais, mirroring the English maneuvers along the river Somme, thus preventing them from reaching Calais without a major confrontation. The result was that d'Albret managed to force Henry into fighting a battle that, given the state of his army, he would have preferred to avoid. The English had very little food, had marched 260 miles in two and a half weeks, were suffering from sickness such as dysentery, and faced large numbers of experienced, well equipped Frenchmen.

However, the French suffered a catastrophic defeat, not just in terms of the sheer numbers killed, but because of the number of high-ranking nobles lost. Henry was able to fulfill all his objectives. He was recognized by the French in the Treaty of Troyes (1420) as the regent and heir to the French throne. This was cemented by his marriage to Catherine of Valois, the daughter of King Charles VI.

Despite this, Henry did not live to inherit the throne of France. In 1422, while securing his position against further French opposition, he died of dysentery at the age of 34. When Charles died, two months later, he was succeeded by Charles VII.

Henry was succeeded by his young son, Henry VI, under whose reign the English were expelled from all of France except Calais, by French forces inspired by Joan of Arc.

The battle

Situation

Henry and his troops were marching to Calais to embark for England, when he was intercepted by French forces. It is believed the French outnumbered the English throughout this encounter; however, it is very difficult to accurately estimate the numbers on both sides. Estimates vary from 6,000 to 9,000 for the English, and from about 15,000 to about 36,000 for the French.

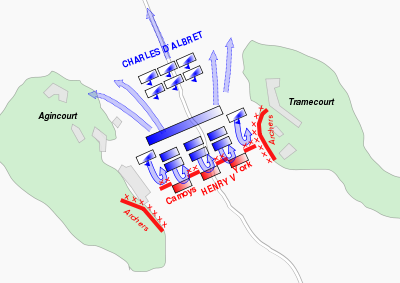

The battle was fought in the narrow strip of open land formed between the woods of Tramecourt and Agincourt (close to the modern village of Azincourt). The French army was positioned by d'Albret at the northern exit so as to bar the way to Calais.

Early on the 25, Henry deployed his army (approximately 900 men-at-arms and 5,000 longbowmen) across a 750 yard part of the defile. It is likely that the English adopted their usual battle line of longbowmen on either flank, men-at-arms and knights in the center, and at the very center roughly 200 archers. The English men-at-arms in plate and mail were placed shoulder to shoulder four deep. The English archers on the flanks drove pointed wooden stakes called palings into the ground at an angle to force cavalry to veer off. It has been argued that fresh men were brought in after the siege of Harfleur; however, other historians argue that this is wrong, and that although 9,200 English left Harfleur, after more sickness set in, they were down to roughly 5,900 by the time of the battle.

French accounts state that, prior to the battle, Henry V gave a speech reassuring his nobles that if the French prevailed, the English nobles would be spared, to be captured and ransomed instead. However, the common soldier would have no such luck and therefore he told them they had better fight for their lives.

The French were arrayed in three lines, called "battles," each with roughly 6,000; however, the first is thought to have swelled to nearly 9,000. Situated on each flank were smaller "wings" of mounted men-at-arms and French Nobles (probably 2,400 in total, 1,200 on each wing), while the center contained dismounted men-at-arms, many of whom were French scions, including twelve princes of royal blood. The rear was made up of 6,000-9,000 of late arriving men-at-arms and armed servants known as "gros varlets." The 4,000-6,000 French crossbowmen and archers were posted in front of the men-at-arms in center.

The terrain

The deciding factor for the outcome was the terrain. The narrow field of battle, recently ploughed land hemmed in by dense woodland, favored the English.[1] The 900 English men-at-arms are described as shoulder to shoulder and four deep, which implies a tight line about 225 men long (perhaps split in two by a central group of archers). The remainder of the field would have been filled with the longbowmen behind their palings. The French first line contained between six and nine thousand men-at-arms, outnumbering the English men-at-arms more than six to one, but they had no way to outflank the English line. The French, divided into the three battles, one behind the other at their initial starting position, could not bring all their forces to bear: The initial engagement was between the English army and the first battle line of the French. When the second French battle line started their advance, the soldiers were pushed closer together and their effectiveness was reduced. Casualties in the front line from longbow fire would also have increased the congestion, as following men would have to walk around the fallen. The density reached four men per square meter, soldiers could not even take full steps forward, lowering the speed of the advance by 70 percent. Accounts of the battle describe the French engaging the English men-at-arms before being rushed from the sides by the longbowmen as the melee developed.

The fighting

On the morning of the 25, the French were still waiting for additional troops to arrive. The Duke of Brabant, the Duke of Anjou and the Duke of Brittany, each commanding 1,000â2,000 fighting men, were all marching to join the army. This left the French with a question of whether or not to advance towards the English. Shakespeare has Henry deliver an inspirational speech before the start of battle, in which he tells his men:

- For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

- Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

- This day shall gentle his condition;

- And gentlemen in England now-a-bed

- Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here,

- And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

- That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.[2]

For three hours after sunrise there was no fighting, until Henry, finding that the French would not advance, moved his army further into the defile. Within extreme bowshot from the French line (300 yards), the archers dug in palings (long stakes pointed outwards toward the enemy), and opened the engagement with a barrage of arrows. The use of palings was an innovation: During the battles of Crécy and Poitiers, two similar engagements between the French and the English, the archers did not use them.

The French at this point lost some of their discipline and the mounted wings charged the longbowmen, but it was a disaster, with the French knights unable to outflank the longbowmen (because of the encroaching woodland) and unable to charge through the palings that protected the archers. The longbows' main influence on the battle was at this point: Only armored on the head, many horses would have become dangerously out of control when struck in the back or flank from the high-elevation shots used as the charge started. The effect of the mounted charge and then retreat was to further churn up the mud the French had to cross to reach the English.

Following the knights' charge, the constable himself then led the attack by the line of dismounted men-at-arms. They outnumbered the English men-at-arms by several times, but weighed down by armor and sinking deep into the mud with every step, they struggled to close the distance and reach their enemies. The mud was knee-deep or worse in places, and the French men-at-arms would have been very slow, and easy targets for the English bowmen. Armour technology at this stage in history had become more advanced than in the earlier medieval period but was still vulnerable to longbow arrows, especially at close ranges where the longbow was said to have penetrated plate visors and armor as if it were cloth. However, the archers quickly ran out of arrows and resorted to the daggers, or leaden mallets many of them carried to drive in the stakes, and engaged the French knights.[3]

The thin line of English men-at-arms was pushed back and Henry himself was almost beaten to the ground. However, because of the number of men they had brought into the battlefield, and the fact that the battlefield narrowed towards the English end, the French found themselves far too closely packed, and had trouble using their weapons properly. At this moment, the archers, using hatchets, swords, and other weapons, attacked the now disordered and fatigued French, who could not cope with their unarmored assailants (who were much less hindered by the mud), and were slaughtered or taken prisoner. By this time the second line of the French had already attacked, only to be engulfed in the mĂȘlĂ©e. Its leaders, like those of the first line, were killed or captured, and the commanders of the third line sought and found their death in the battle, while their men rode off to safety.

One of the best anecdotes of the battle involves Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, Henry V's youngest brother. According to the story, Henry, upon hearing that his brother had been wounded in the abdomen, took his household guard and cut a path through the French, standing over his brother and beating back waves of soldiers until Humphrey could be dragged to safety.

The only French success was a sally from Agincourt Castle behind the lines. Ysambart D'Agincourt with 1,000 peasants seized the King's baggage. Thinking his rear was under attack and worried that the prisoners would rearm themselves with the weapons strewn upon the field, Henry ordered their slaughter. The nobles and senior officers, wishing to ransom the captives (and perhaps from a sense of honor, having received the surrender of the prisoners), refused. The task fell to the common soldiers. It is believed more Frenchmen died in this slaughter than in the battle itself.

The aftermath

The next morning, Henry returned to the battlefield and ordered the killing of any wounded Frenchmen who had survived the night out in the open. All of the nobility had already been taken away. It is likely that any commoners left on the field were too badly injured to survive without medical care.

Due to a lack of reliable sources it is impossible to give a precise figure for the French and English casualties. However, it is clear that though the English were considerably outnumbered, their losses were much lower than those of the French.

Claims that the English lost only thirteen men-at-arms (including Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York, a grandson of Edward III) and about 100 foot soldiers are quite unlikely, given the ferocity of the fighting. Henry deliberately concealed the actual losses by paying the English retinues at their pre-battle strengths while quickly spreading the story of only minor losses, which persists to this day. One fairly widely used estimate puts the English casualties at 450, not an insignificant number in an army of 6,000, but far less than the thousands the French lost.

The French suffered heavily, mainly because of the massacre of the prisoners. The constable, three dukes, five counts, and 90 barons were among the dead, and a number of notable prisoners were taken, amongst them the Duke of Orléans (the famous poet Charles d'Orléans) and Jean Le Maingre, Marshal of France.

The Battle of Agincourt did not result in Henry conquering France, but it did allow him to escape and renew the war two years later.

Notable casualties

- Antoine of Burgundy, Duke of Brabant and Limburg (b. 1384)

- Philip of Burgundy, Count of Nevers and Rethel (b. 1389)

- Charles I d'Albret, Count of Dreux, the Constable of France

- John II, Count of Bethune (b. 1359)

- John I, Duke of Alençon (b. 1385)

- Frederick of Lorraine, Count of Vaudemont (b. 1371)

- Robert, Count of Marles and Soissons

- Edward III, Duke of Bar (the Duchy of Bar lost its independence as a consequence of his death)

- John VI, Count of Roucy

- Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York (b. 1373)

- Earl of Suffolk

Notes

- â David Wason, Battlefield Detectives (London: Carlton Books, 2004), p. 74. ISBN 0233050833

- â www.agnic.net, The Battle of Agincourt. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- â Barker, 2005.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barker, Juliet R. V. Agincourt: Henry V and the Battle that Made England. New York: Little, Brown and Co., 2006. ISBN 9780316015035

- Curry, Anne. Agincourt: A New History. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus, 2005. ISBN 9780752428284

- Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor Nevitt Dupuy. The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History: From 3500 B.C.E. to the Present. New York: HarperCollins, 1993. ISBN 9780062700568

- Keegan, John. The Face of Battle: A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1988. ISBN 9780140048971

External links

All links retrieved September 20, 2023.

- Agincourt with Anne Curry, Michael Jones and John Watts

- Agincourt 1415: Henry V, Sir Thomas Erpingham and the triumph of the English archers

- The Battle of Agincourt

- The Battle of Agincourt

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.