Battle of Mohi

The Battle of Mohi, or Battle of the Sajó River, (on April 11, 1241) was the main battle between the Mongols under Subutai and the Kingdom of Hungary under Béla IV during the Mongol invasion of Europe. It took place at Muhi or Mohi, southwest of the Sajó River. Mongol use of heavy machinery demonstrated how military engineering could be put to effective and strategic use. After the invasion, Hungary lay in ruins. Nearly half of the inhabited places had been destroyed by the invading armies. Around a quarter of the population was lost, mostly in lowland areas, especially in the Great Hungarian Plain, where there were hardly any survivors; in the southern reaches of the Hungarian plain in the area now called the Banat, and in southern Transylvania.

Soon after the battle, Ögedei Khan died, so Subutai and his Mongols were recalled to Mongolia so that he could take part in the election of a new Great Khan. Effectively, this brought the Mongol invasion of Europe to an end, turning the Battle of Mohi, although a defeat for the Europeans, into an iconic event in the history of East-West relations. Yet, what was most significant about the Mongol advance towards Europe was the opening up of communication, travel, and trade between East and West. Gunpowder, porcelain, and the technology of papermaking went West in return for perfume, precious stones, and certain textiles among other items. As Europeans established diplomatic relations with the Mongols, too, Europeans became more intellectually open to ideas and value in other cultures. Although Europeans would be guilty of racist, religious and civilizational arrogance during their colonial era and at other times in history, early European-Mongol encounter contains seeds of an alternative world-view. This alternative view recognizes that East and West each benefit from cultural and economic exchange, and can be partners rather than rivals.

Background

In 1223, the expanding Mongol Empire defeated an allied Cuman army at the Kalka river. The defeated Cumans retreated towards Hungary. Hungary had continuously tried to convert the Cumans to Christianity and expand its influence over the Cuman tribes for the past few decades. The Hungarian King Béla IV even began to use the title "King of Cumania." When the Cuman refugees (c. 40,000 people) sought [[political asylum|asylum in his kingdom, it seemed that at least a portion of the Cumans had accepted Hungarian rule. The Mongols considered the Cumans to be their slaves, saw Hungary as a rival, and the Cuman migration to Hungary as a casus belli. In their ultimatum they also blamed Hungary for missing envoys.

The Mongolian threat approached Hungary during a time of political turmoil. Traditionally, the base of royal power consisted of the vast estates owned as royal property. Under Andrew II, the donations of land by the crown reached a new peak. Whole counties were donated. After Béla IV inherited his father's throne he began to re-confiscate Andrew’s donations and to execute or expel his advisers. He also denied the lord's right of personal hearings and accepted only written petitions to his chancellery. He even had the chairs of the council chamber taken away in order to force everybody to stand in his presence. His actions caused great disaffection among the lords. The newly arrived Cumans gave the king a better position (and increased prestige among Church circles for converting them) but also caused a lot of problems. The nomadic Cumans seemed unable to live together with the settled Hungarians and the lords were shocked that the king supported the Cumans in quarrels between the two.

The battle

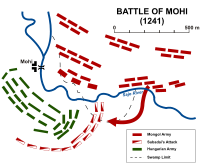

The Mongols attacked Hungary with three armies. One of them attacked through Poland in order to withhold possible Polish auxiliaries and defeated the army of Duke Henry II the Pious of Silesia at the Legnica. Duke Henry was slain (after trying to retreat) and "nine sacks of ears" collected by the victors "attested to the heavy losses of the defeated."[1] A southern army attacked Transylvania, defeated the Voivode (military commander) and crushed the Transylvanian Hungarian army. The main army led by Khan Batu and Subutai attacked Hungary through the fortified Verecke Pass and annihilated the army led by the count Palatine on March 12, 1241.

King Béla IV began to mobilize his army and ordered all of his troops, including the Cumans, to the city of Pest. Frederick II, Duke of Austria and Styria, also arrived there to help him. In this moment, the conflict between Cumans and Hungarians caused riots and the Cuman khan—who had been under the personal protection of the king—was murdered. Some sources mention the role of Duke Frederick in inciting this riot, but his true role is unknown. The Cumans believed that they had been betrayed, and left the country to the south, pillaging all the way. The full mobilization was unsuccessful. Many contingents were unable to reach Pest; some were destroyed by Mongols before they arrived, some by renegade Cumans. Many nobles refused to take part in the campaign because they hated the king and desired his downfall. Hardly anybody believed that the Mongol attack was a serious threat to the kingdom's security, and the Cuman defection was considered minor and usual. This attitude may have contributed to the death of the Cuman Khan Kuthen (or Kutan) who was killed during civil uprising among the Cuman.[2]

The Tartar vanguard reached Pest on March 15th and began to pillage the neighboring area. King Béla forbade his men to attack them, as the Hungarian army was still unprepared. Even so, Duke Frederick attacked and defeated a minor raiding party, so Béla came to be seen as a coward. After this "heroic" act, Duke Frederick returned home. Ugrin Csák, the archbishop of Kalocsa, also tried to attack a Mongol contingent, but he was lured to a swamp and his armored cavalry became irretrievably stuck in it. He barely escaped with his own life.

Finally, the king decided to offer battle with the Tartars, but they began to retreat. This affirmed the opinion of the lords that the Tartars were not a threat and the king’s behavior was not caution, but cowardice. After a week of forced marches and regular Tartar attacks, the Hungarian army reached the flooded river Sajó. Here the army stopped to rest and to wait for additional supplies. The king and the Hungarians still did not know that the main Tartar army, which numbered between 20,000 and 30,000, in contrast to the approximately 15,000-strong collection of varied Hungarian forces, was present, because of the wooded terrain on the far bank of the Sajó. The cautious king ordered the building of a heavily fortified camp of wagon trains.

It is highly unlikely that the Mongols originally wanted to cross a wide and dangerous river to attack a fortified camp. It is more likely that their original plan was to attack the Hungarians while crossing the river just as in the case of the Battle of the Kalka River. The original Mongol attack plan is still unclear. A Ruthenian slave of the Tartars escaped to the Hungarians, warning of a possible night attack across the Sajó bridge.

The Hungarians still did not believe that this would be a full scale attack, but the troops of Prince Kálmán, Duke of Slavonia, and the younger brother of king Béla, and archbishop Ugrin Csák with the Templar master left the camp to surprise the Tartars and defend the unguarded bridge. They reached the bridge at midnight. The sun set at 18:29, so they had to march 7 kilometers in darkness. It is very unlikely that the Mongols wanted to attack at night (horse archers avoid night battles), but they did need to cross the river to be able to attack the Hungarian camp at dawn. When Kálmán and Ugrin arrived they found the Tartars unprepared and in the middle of crossing the river. They successfully forced them into pitched battle and achieved a great victory at the bridge. The Mongols were totally unprepared for the crossbowmen who inflicted considerable losses on the Mongol forces, especially due to the size of the bridge, which was a minimum of 200 meters long. The Hungarians left some soldiers to guard the bridge and returned to the camp, unaware that the main Mongol army was still there. When they arrived at the camp around 2 a.m., they celebrated their victory.

The unexpected Hungarian victory forced the Mongol generals to modify their plans. Sejban was sent north to a ford with a smaller force to cross the river and attack the back of the bridgeguard. At about 4 a.m., as the daylight they required started to break, they began the crossing. Meanwhile, Subutai went south to build a makeshift emergency bridge while the Hungarians were engaged at the main bridge, but left Batu a plan to use giant stone throwers, which the Hungarians had probably never seen, to clear the crossbowmen opposing them. At dawn, Batu, with the help of seven stone throwers, attacked the Hungarian guards on the bridge and after the subsequent arrival of Sejban and his men, the Hungarians retreated to their camp. The Mongol main forces finished crossing the river around 8 a.m.

When the fleeing Hungarians arrived at the camp they woke up the others. Kálmán, Ugrin, and the Templar master left the camp again to deal with the attackers. Others remained there, believing this was also a minor attack and that Prince Kálmán would again claim victory. But as Kálmán and Ugrin witnessed the horde of Tartars swell, they realized that this was not a minor raid, but a very dangerous attack of the main Mongol force. After some heavy fighting they returned to the camp to reinforce themselves and to return with the full army. They were badly disappointed, as the king had not even issued orders to prepare for the battle. Archbishop Ugrin reproached the king for his faults in public, and finally the Hungarian army sallied forth, but this delay gave enough time to Batu to finish the crossing. A hard struggle ensued. The Hungarians outnumbered Batu's troops and the Tartars were unable to move quickly because the Sajó was behind their backs. Chinese and Mongol sources mention that Batu lost 30 of his bodyguards and one of his lieutenants, Bakatu, and only the personal action and bravery of Batu kept the horde from breaking and fleeing the field. At this moment, Subutai who had been delayed by bridge-building, attacked the Hungarians’ rear flank, causing the panicked Hungarians to retreat to their camp.

It is possible that the Hungarians might have had the capability to defend the camp, but sallying was ineffective, and they were terrified by the flaming arrows, resulting in the deaths of many soldiers by the trampling crush of their comrades. The Mongols used "catapults, flame throwers" and "possibly gunpowder bombs."[3] Finally, the demoralized soldiers routed and tried to escape through a gap left open on purpose (A Chinese plan stated in Sun Tzu's Art of War[4]) by the Mongols, a plan chosen because fleeing soldiers can be killed more easily than those who, with their backs to a wall, are forced to fight till death. However, the Tartar casualties had been so large that, at this point, Batu did not want to pursue the Hungarians. However, Subutai exhorted him successfully and the Mongols attacked. Archbishop Ugrin (as was another archbishop) was killed, but Kálmán and Béla managed to escape, though the wounds of Kálmán were so serious that he died soon after. Some 65,000 men are said to have died.[2] The Hungarians lost nearly 10,000 men and were unable to field another army to contain the remaining Tartar. After the victory, the Tartars regrouped and began a systematic assault on the rest of the nation.

Aftermath

After the battle, there was no other major organized force capable of halting the advance of the Mongols; defeating them completely was unthinkable. An attempt was made to hold off the main Mongol army at the Danube, which was mostly successful from April 1241 until January 1242. In an unusually cold winter, the river froze over, and after a number of close battles, the Mongols managed to cross. The royal family escaped to Austria to seek help from their ally Duke Frederick, but instead he arrested them and extorted an enormous ransom in gold and forced the king to cede three western counties to Austria. It was at this point that the King and some of his retinue fled southwest, through Hungarian-controlled territory, to the Adriatic coast and the castle of Trogir, where they stayed until the Mongols retreated. While the king kept himself apprised of the situation in the rest of the country, he made numerous attempts to contact other rulers of Europe, including the Pope Innocent IV, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the King of France, but none seemed interested, and all seemed to have the same profound misunderstanding of the threat posed by the Mongol armies, which stood by this time within a week's ride from the borders of France.

Meanwhile, in the main territory of Hungary, surviving members of the royal retinue, being for the large part those that did not get to the battle of Mohi in time to participate, along with a number of unorganized irregulars consisting mostly of armed peasants, employing guerrilla tactics, continued to harass Mongol troops, even occasionally successfully engaging them in open battle. Much of the civilian population fled to areas of refuge inaccessible to the Mongol cavalry: high mountains in the north and east; swamps, especially on the puszta (or bushy wilderness), around Székesfehérvár, and in the west (the Hanság); and older earthwork fortresses, most of which were in a Motte-and-bailey form or consisted of a mud-banked enclosure on the top of a mountain, steep natural hill, or man-made hill. Rogerius recounts his experience in one such refuge called Fátra in his Carmen Miserabile (Sad Song for the destruction of the Kingdom of Hungary by the Tartars).[5] Such places are often referred to by the German term Fluchtburg.

Subutai's recall

In 1242, the Great Khan Ögedei died and ultimately this led the Mongols to retreat so that the princes of the blood could be present for the election of a new Great Khan. Just prior to their departure, the Mongol army was having difficulty with the pacification of the country, though they made plans to attack Austria and eventually Germany and Italy. While the defeat of the Hungarian army at the Sajó river is most often described in a couple of sentences as an effortless rout by the Mongols of the Hungarian army, this is an oversimplification. The Hungarian army as well as irregulars from the countryside proved dangerous foes and Mongol losses were not insignificant. Subutai's engineers faced additional difficulties in constructing a bridge in the deeper than expected waters, and managed to attack the Hungarian rear just in time, as Batu's forces were being stretched and taxed by the numerically superior Hungarian forces.

By the mid-thirteenth century, the Hungarian army had lost the tactics of the steppe nomads that made them such effective fighters against the German states, France, Italy, Spain, Poland, the Balkans and the present Netherlands in the ninth and tenth centuries. But there is some doubt in this regard, as some historians have stated that the Hungarian military became more Westernized after the Mongol invasion and because of it; and despite its steppe tactics, early Hungary was still defeated by the Germans in the tenth century and was hardly a threat to France or Spain; whether they had retained steppe tactics or not would not have helped. Outfitted in lighter versions of contemporary European armor equipment, they were often slow, easy targets for swift Mongol archers (this statement however, is likely an oversimplification; the Mongols were simply better tacticians, and there is no indication in the sources that the Hungarians had any problems coming to grips with the Mongols). Still, they managed to nearly defeat the main Mongol force. At one point, Batu Khan's personal guards were being slaughtered and his own life lay in serious danger. At another point, the Mongol troops were being routed by the Hungarian archers followed up by the heavy mounted knights and only the personal bravery of Batu Khan prevented the wholesale flight of his army. Ultimately, only by means of what was essentially a trick (and ironically, one which earlier Hungarian troops used often) did the Mongols manage to defeat the main Hungarian army in open battle.

In spite of this, by Candlemas (February) 1242, more than a year after the initial invasion and a few months before the Mongols' withdrawal, a significant number of important castles and towns had resisted the formidable and infamous Mongol siege tactics. Among the nearly eighty sites that remained unconquered, only three were of the most formidable type: The then-new stone castle on an elevation: Fülek, Léka, near the western border, and Németújvár. The rest were either fortified towns (for example, Székesfehérvár), old comital center castles (Comital towns were where a Count, or Graf, had his seat) (such as Esztergom citadel), fortified monasteries (for example, Tihany and Pannonhalma) or military fortresses (for example, Vécs guarding a main trade route in the mountains of Transylvania). Ultimately, the country was not subdued; and though much of the population was slaughtered, the King and upper nobility avoided capture. As a tardy revenge, the Hungarians and Croats ambushed and destroyed the rearguard division of the retreating Mongol army in the Carpathians.

After the withdrawal of the Mongol troops, they were never again to return to Hungary with a force capable of laying siege to fortified cities, as the Chinese bombardiers and engineers under general Subutai were no longer deployed in the European theater of operations; Subutai was reassigned by Guyuk to engage the Southern Song, and died of old age in 1248. Hungary lay in ruins. Nearly half of the inhabited places had been destroyed by the invading armies. Around a quarter of the population was lost, mostly in lowland areas, especially in the Alföld, where there were hardly any survivors; in the southern reaches of the Hungarian plain in the area now called the Banat, and in southern Transylvania.

However, the power of the kingdom was not broken. Within a year of the withdrawal of the Mongols, the three westernmost counties (Moson, Sopron, and Vas) that were extorted as ransom by Duke Frederick of Austria were recaptured, and a local uprising in Slavonia was quashed. The threat of another Mongol invasion, this time taken seriously, was the source of exceptional national unity and provided the impetus for Bela IV's extensive expansion of Hungarian defenses, especially the building of new stone castles (forty-four in the first ten years) and the revitalization of the army, including expanding the number of heavily armored cavalry in the royal army. Béla IV is seen now as a second founder of the nation, partly in recognition of all that was done during his reign to reconstruct and fortify the country against foreign invasion from the east. These improvements were to pay off, in 1284, when Nogai Khan attempted an invasion of the country. In that event, the invasion was defeated handily, as were a number of other minor attacks before and after. In the coming centuries, as the power of the Mongols of the Russian steppe waned and western defenses became more capable, the attention of countries of central Europe would increasingly be directed to the southeast, and the growing power of the Ottoman Empire.

Legacy

Bela IV set about rebuilding and re-fortifying his country, earning the title of Hungary's "second founder."[6] Although the Mongols intervened "in Hungarian affairs in the 1280s and 1290s, they never again threatened Western Europe" and after 1260, "the Mongol empire split into four parts, the Chaghadai khanate in central Asia, the Yuan Dynasty in China … the Il-Khans of Persia and the Golden Horde in Russia."[7] From a military point of view, the Battle of Mohi was significant for its use of engineering tactics by the Mongols, from which their enemies learned some lessons in strategy.

On the one hand, Europeans saw the Mongols as a threat, although Europeans in the West appear to have been content to let the Hungarians and others in Eastern Europe serve as a buffer-zone, thus protecting their own territory. On the other hand, the Mongols' arrival on the borders of the European space from the East reminded Europeans that a world existed beyond their horizons. The political stability, sometimes called the Pax Mongolia, that Ögedei established throughout Asia re-established the Silk Road, the primary trading route between East and West. Before long, Marco Polo was traveling this route, followed by others. The Mongols absorbed local customs wherever they settled, so helped to build bridges between some of the world's cultures. Lane says that this facilitation of cultural exchange was not accidental but that the Mongols regarded themselves as "cultural brokers," so often it was their own policies that "launched these exchanges … they initiated population movement, financed trade caravans, established industries and farms and created the markets for the goods that began to crisscross their vast empire." They "remained involved in the whole business of commercial and cultural exchange at every level," he says, "and in every area."[8] Guzman says that it was contact with the Mongols that "ended Europe's geographical isolation, moved Christian Europe toward ecumenism and toleration, and broadened Europe's intellectual horizons." Later, when diplomatic relations were established between Europeans[9] and various Mongol polities, diplomacy began to emerge as much more important way of dealing with relations between different states and political entities. Early European-Mongol contact, says Guzman, "represented Europe's first true intercultural experience and is of critical importance in evaluating and understanding the growth and development of Western intellectual history especially in the emergence of a European world-view of mankind and history."[9]

Notes

- ↑ Saunders (1971), 85.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Saunders (1971), 86.

- ↑ Archer (2002), 180.

- ↑ Sun Tzu and Gilers, Lionel, The Art of War, China Page. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ↑ Rogerius, and Helmut Stefan Milletich, Carmen miserabile: Lateinisch/Deutsch (Eisenstadt, DE: Edition Roetzer, 1979, ISBN 9783853740477).

- ↑ The Free Dictionary, Hungary: history to 1918. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ↑ Archer (2002), 181.

- ↑ Lane. 2004. pages 97-98.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gregory Guzman, Christian Europe and Mongol Asia: First Medieval Intercultural Contact Between East and West, in Mark D. Johnston and Samuel M. Riley, Essays in Medieval Studies (Chicago, IL: Loyola University, 1999). Retrieved October 17, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven. The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0521462266

- Archer, Christon I. World History of Warfare. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0803244238

- Gabriel, Richard A. Subotai the Valiant: Genghis Khan's Greatest General. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004. ISBN 978-0275975821

- Lane, George. Genghis Khan and Mongol Rule. Greenwood guides to historic events of the medieval world. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0313325281

- Morgan, David. The Mongols. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford, UK: B. Blackwell, 1986. ISBN 978-0631135562

- Nicolle, David, and Richard Hook. 1998. The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. London, UK: Brookhampton Press, 1986. ISBN 978-1860194078

- Regan, Geoffrey. The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles. New York, UK: Canopy Books, 1992. ISBN 1558594310

- Saunders, J.J. The History of the Mongol Conquests. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 1971. ISBN 978-0389044512

- Sicker, Martin. The Islamic World in Ascendancy From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000. ISBN 9780313001116

- Soucek, Svatopluk. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0521651691

- Kosztolnyik, Z.J. Hungary in the Thirteenth Century. East European monographs, no. 439. Boulder, CO: East European Monographs, 1996. ISBN 9780880333368

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.