Black Kettle

Chief Black Kettle or Moketavato (born ca. 1803-1813 in present-day South Dakota; died November 27, 1868 on the Washita River, Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma), was a traditional Cheyenne chief in the days of America's Westward Expansion. In the effort to keep peace and create harmonious co-existance with white settlers, he negotiated treaty after treaty, with the terms of each being broken by the U.S. government one after the other.

Black Kettle survived the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 but died in 1868 at the Massacre at Washita River, several days after seeking sanctuary for his people within governmental fort confines. He was one of the best-known of the traditional Cheyenne Chiefs, otherwise known as "Peace Chiefs." Black Kettle continues to be honored as a prominent leader who never ceased striving for peace, though it eventually cost him his life.

Early Life

Little is known of Black Kettle's life prior to 1854, when he was made a chief of the Council of Forty-four, except that he was an able warrior in the traditional Cheyenne manner.

The Council of Forty-four was one of the two central institutions of traditional Cheyenne Indian tribal governance, the other being the military societies such as the Dog Soldiers. The influence of the Council of Forty-four waned in the face of internal conflict among the Cheyenne regarding Cheyenne policy toward encroaching white settlers on the Great Plains, and was dealt a severe blow by the Sand Creek Massacre.

Cheyenne-American relations had been governed by the Treaty of Fort Laramie since 1851. However, American expansion into the Great Plains continued apace, especially after the Pike's Peak Gold Rush beginning in 1858. The Cheyenne continued to be displaced from their lands. By the 1860s, as conflict between Indians and encroaching whites intensified, the influence wielded by the militaristic Dog Soldiers, together with that of the military societies within other Cheyenne bands, had become a significant counter to the influence of the traditional Council of Forty-four chiefs, who continuously strove to attain peace with the whites.[1]

Traditional (Peace) chiefs versus militant chiefs

There are those who describe Black Kettle as a pragmatist who believed that American military power was overwhelming, and he thus adopted a policy of dialogue rather than war. This may have been an accurate description of his character, but he was also strongly influenced by his education as a peace chief.

Cheyenne tradition holds that the first peace chief was appointed by Sweet Medicine, who established a code of conduct for all such future chiefs. This code indicated that a peace chief was to abandon all violence, even in the face of imminent danger. Yet he was to stand firm, even nonaggressively, against all opponents of his people, maintaining this position even after the soldier societies might have retreated. Though the younger generation of Cheyenne warriors might defy the peace chiefs, they were to persist in peacemaking efforts. This policy was not restricted by race; peace was to be sought in this manner with both Native and White. The peace chief was educated to show generosity in dealing with his own people, especially the poor.[2]

The Sand Creek Massacre of November 29, 1864, besides causing a heavy loss of life and material possessions by the Cheyenne and Arapaho bands present at Sand Creek, also devastated the Cheyenne's traditional government, due to the deaths at Sand Creek of eight of 44 members of the Council of Forty-four, including White Antelope, One Eye, Yellow Wolf, Big Man, Bear Man, War Bonnet, Spotted Crow, and Bear Robe, as well as headmen of some of the Cheyenne's military societies. Among the chiefs killed were most of those who had advocated peace with white settlers and the U.S. government.[1]

The effect of this on Cheyenne society was to exacerbate the social and political rift between the traditional council chiefs and their followers on the one hand and the Dog Soldiers on the other. To the Dog Soldiers, the Sand Creek Massacre illustrated the folly of the peace chiefs' policy of accommodating the whites through the signing of treaties such as the first Treaty of Fort Laramie and the Treaty of Fort Wise and vindicated the Dog Soldiers' own militant posture towards the whites. The traditional Cheyenne clan system, upon which the system of choosing chiefs for the Council of Forty-four depended, was dealt a fatal blow by the events at Sand Creek. The authority of traditional Council chiefs, such as Black Kettle, to moderate the behavior of the tribe's young men and to deal with whites was severely hampered by these events as well as by the ascendancy of the Dog Soldiers' militant policies.[1]

Wars and treaties

Black Kettle accepted the highly unfavorable Treaty of Fort Wise in 1861, which confined the Cheyenne to the Sand Creek Reservation, a small corner of Southeastern Colorado. The land was unfit for agriculture and far from any buffalo. Many Cheyenne warriors including the Dog Soldiers would not accept this treaty, and began to launch punitive attacks against White settlers.

The Colorado War

By the summer of 1864 the situation was at boiling point. Cheyenne hardliners and the allied Kiowa and Arapaho continued raiding American settlements, sometimes taking prisoners including women and children. On July 11, 1864, the Hungate massacre of a family of settlers further inflamed matters, especially after pro-war whites publicly exhibited the bodies in Denver. Colorado governor John Evans believed the attack had been ordered by tribal chiefs and presaged a full-scale war.

Evans proclaimed that all "Friendly Indians of the Plains" must report to military posts or be considered hostile. He received authorization from the War Department to establish the Third Colorado Cavalry. The unit, composed of "100-daysers" who had signed on specifically to fight Indians, was led by John Chivington.

Black Kettle decided to accept Evans' offer, and entered negotiations. On September 28 he concluded a peace settlement at Camp Weld outside Denver. The agreement confined the Cheyenne to the Sand Creek reservation and required them to report to Fort Lyon, formerly Fort Wise. Black Kettle believed this agreement would ensure the safety of his people. He was mistaken.

Betrayal at Sand Creek

On November 28, Chivington arrived at Fort Lyon with his men. According to an eyewitness, "he stopped all persons from going on ahead of him. He stopped the mail, and would not allow any person to go on ahead of him at the time he was on his way from Denver city to Fort Lyon. He placed a guard around old Colonel Bent, the former agent there; he stopped a Mr. Hagues and many men who were on their way to Fort Lyon. He took the fort by surprise, and as soon as he got there he posted pickets all around the fort, and then left at 8 o'clock that night for this Indian camp."

At dawn on the 29th, Chivington attacked the Sand Creek reservation. Following instructions, Black Kettle flew an American flag and a white flag from his tipi, but the signal was ignored. An estimated 250-400 were shot or stabbed to death, and the settlement was put to the torch. Most of the victims were women and children. Chivington proudly displayed trophies of his "battle," including body parts, in Denver for months following.

Aftermath

Black Kettle escaped the massacre, and returned to rescue his badly injured wife. Even after this outrage, he continued to counsel pacifism, believing that military resistance was doomed to fail. The majority of Cheyenne tribes disagreed, and launched all-out warfare in alliance with the Comanche and Kiowa. Black Kettle instead moved south and continued to negotiate.

Black Kettle's efforts resulted in the Treaty of Little Arkansas River on October 14, 1864. This document promised "perpetual peace" and lands in reparation for the Sand Creek massacre. However, its practical effect was to dispossess the Cheyenne yet again. Black Kettle's influence continued to wane, and the hard line favored by Roman Nose and his Dog Soldiers became dominant.

Medicine Lodge treaty

Black Kettle's dwindling band proclaimed their desire to live peacefully alongside Americans. Black Kettle signed yet another treaty, the Medicine Lodge Treaty on October 28, 1867. However, Dog Soldiers continued their raids and ambushes across Kansas, Texas, and Colorado. The exact relationship between the two groups is a subject of dispute. According to Little Rock, second-in-command of Black Kettle's village, most of the warriors came back to Black Kettle's camp after their massacres. White prisoners including children were held within his encampment. By this time Black Kettle's influence was waning, and it is questionable whether he could have stopped any of this.

Death and legacy

Major General Philip H. Sheridan, commander of the Department of the Missouri, adopted a policy that "punishment must follow crime." Unfortunately, Sheridan, like many Americans of the time, did not differentiate between tribes or bands within a tribe—an Indian was an Indian.

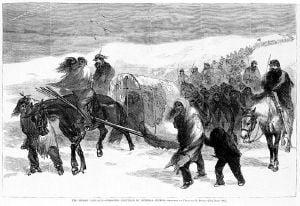

In retaliation for the Kansas raids which had been committed, not by Black Kettle's group, but by the militant Cheyenne and their allies, Sheridan planned to mount a winter campaign when Indian horses would be weak and unfit for all but the most limited service.

In November of 1868, Black Kettle and Arapaho Chief Big Mouth went to Fort Cobb to petition General William B. Hazen for peace and protection. Though he had proven himself peaceful, his request to bring his people into Fort Cobb for protection was denied. Hazen told him that only Sheridan or Lt. Col. George Custer could approve such a request. Black Kettle and his band returned to their camp at the Washita River. Though his wife and others had suggested they move farther downriver, closer to larger encampments of Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Apache for protection, he resisted. He did not believe that Sheridan would order an attack without first offering an opportunity for peace.[3]

Under orders from Sheridan, Custer marched south on November 23 with about 800 soldiers, traveling through a foot of snow. After four days of travel, they reached the Washita valley shortly after midnight on November 27, and silently took up a position near Black Kettle's encampment. The soldiers attacked the 51 lodges before dawn killing a number of men, women, and children. Custer's report included about 100 killed, though Cheyenne accounts claimed 11 warriors plus 19 women and children had died. More than 50 were taken captive, mainly women and children. American losses were small, with two officers and 19 enlisted men killed. Most of the soldier casualties belonged to Major Joel Elliott's detachment, whose eastward foray was overrun by Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa warriors coming to Black Kettle's aid. Chief Black Kettle and his wife were killed in the attack.[3]

Following the slaughter of the sleeping village, the group slaughtered the Indian pony and mule herd, estimated at more than 800 animals. The lodges of Black Kettle's people, with all their winter supply of food and clothing, were torched. They then quickly retreated to Camp Supply with their hostages.

Black Kettle is buried in the Indian Cemetery in Colony, Oklahoma. Not only did Black Kettle die at Washita; so did the Cheyenne's hopes of continuing as an independent and free people. By the following year, all had been driven from the plains and confined to reservations.

In April 1996, the United Methodist Church, at its national convention in Denver, formally apologized to the Arapaho and Cheyenne Indian tribes for the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864.[4]

On November 12, 1996, the Washita Battlefield National Historic Site was authorized by the U.S. Government. The 315 acre site preserves the location of the encampment of Black Kettle in which he was killed in the pre-dawn surprise attack. It is located near the town of Cheyenne, Oklahoma.

Black Kettle continues to be honored as a prominent leader who never ceased striving for peace, though it eventually cost him his life.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Jerome A. Greene, Washita, The Southern Cheyenne and the U.S. Army, Campaigns and Commanders Series, vol. 3. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 23-27.

- ↑ Harvey Markowitz and Carole A. Barrett, American Indian biographies, Magill's choice (Pasadena, Calif: Salem Press, 2005), 49.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 National Park Service, The Story of the Battle of the Washita Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ↑ Last of the Independents, Black Kettle (1813-1868) Retrieved May 10, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Print sources

- Brown, Dee Alexander. Bury my heart at Wounded Knee; an Indian history of the American West. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1971. ISBN 0030853222

- Greene, Jerome A. Washita, The Southern Cheyenne and the U.S. Army. Campaigns and Commanders Series, vol. 3. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004. ISBN 0806135514

- Hardorff, Richard G. Washita memories: eyewitness views of Custer's attack on Black Kettle's village. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0806137599

- Hatch, Thom. Black Kettle: the Cheyenne chief who sought peace but found war. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2004. ISBN 978-0471445920

- Hoig, Stan. The Battle of the Washita: the Sheridan-Custer Indian campaign of 1867-69. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1976. ISBN 0385112742

- Markowitz, Harvey, and Carole A. Barrett. American Indian biographies. Magill's choice. Pasadena, Calif: Salem Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1587652332

- Svaldi, David. Sand Creek and the rhetoric of extermination: a case study in Indian-White relations. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1989. ISBN 0819173142

- Online sources

- Legends of America. Chief Black Kettle - A Peaceful Leader Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- PBS - The West Film Project. Documents on the Sand Creek Massacre Retrieved September 3, 2019.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.