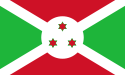

Burundi

| Republika y'u Burundi République du Burundi Republic of Burundi |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Ubumwe, Ibikorwa, Iterambere" (Kirundi) "Unité, Travail, Progrès" (French) "Unity, Work, Progress" (English) |

||||||

| Anthem: Burundi bwacu (Our Burundi) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Bujumbura 3°30′S 30°00′E | |||||

| Official languages | Kirundi (national and official) French (official) English (official)[1] |

|||||

| Ethnic groups | Hutu (Bantu) 85% Tutsi (Hamitic) 14% Twa (Pygmy) 1% Europeans 3,000 South Asians 2,000 |

|||||

| Demonym | Burundian | |||||

| Government | Republic | |||||

| - | President | Évariste Ndayishimiye | ||||

| - | Vice President | Prosper Bazombanza | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Alain-Guillaume Bunyoni | ||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | from Belgium | July 1, 1962 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 27,834 km² (145th) 10,745 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 7.8 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2020 estimate | 11,865,821[2] (84th) | ||||

| - | 2008 census | 8,053,574[3] | ||||

| - | Density | 401.6/km² (20th) 1,040.1/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $8.380 billion | ||||

| - | Per capita | $727[4] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $3.573 billion | ||||

| - | Per capita | $310[4] | ||||

| Gini (2013) | 38.6[5] | |||||

| Currency | Burundi franc (FBu) (BIF) |

|||||

| Time zone | CAT (UTC+2) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .bi | |||||

| Calling code | +257 | |||||

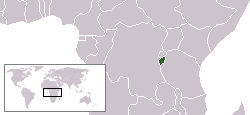

Burundi, officially the Republic of Burundi, is a small country of rolling green hills and mountains in the Great Lakes region of Africa. It is bordered by Rwanda on the north, Tanzania on the south and east, and the Democratic Republic of Congo on the west. Much of its western border is adjacent to Lake Tanganyika, the deepest lake in Africa and the world's longest lake. Though near the Equator, its climate is temperate because of the altitude, which is perhaps why it and neighboring Rwanda are so heavily populated. The country's modern name is derived from its Bantu language, Kirundi.

Geographically isolated, facing population pressures, and having sparse resources, Burundi is one of the poorest and most conflict-ridden countries in Africa and in the world. Its small size belies the magnitude of the problems it faces in reconciling the needs of the Tutsi minority and Hutu majority after centuries of suspicion and oppression.

Burundi experienced three episodes of genocide in the twentieth century, due to the ethnic conflicts between the Hutu and Tutsi tribes. Hundreds of thousands have fled the violence, escaping to neighboring countries Zaire, Rwanda and Tanzania. However, small inter–religious and inter–ethnic groups have joined together in various locations in the country to rebuild their land through the reconstruction of schools, hospitals and homes that have been destroyed througout its years of conflict. This joint effort will also benefit the morale of the people, providing hope through its example of harmony and cooperation.

History

The earliest inhabitants of the area now known as Burundi were the Twa, nomadic Hunter-gatherers who were largely replaced and absorbed by Bantu tribes during the Bantu migrations. By 1000 C.E., Hutu farmers had established themselves in the highlands, organized into chiefdoms. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Tutsi pastoralists with their cattle moved into the valleys. They relied on their cattle for milk, hides, and meat. Though numerically a smaller group, the Tutsis may have been able to gain ascendance as Hutus needed to come to them for employment when their crops failed. Around 1650, a kingdom was established under the Tutsis, with the Hutus largely in a feudal serflike relationship with the Tutsis. Until the downfall of the monarchy in 1966, kingship remained one of last links that bound Burundi with its pre-colonial past.

Burundi was claimed by Germany in 1894, and in 1903, it became a German colony, along with Rwanda, when the king signed a treaty that would keep him in power. During World War I, control passed to Belgium. It became part of the Belgian League of Nations mandate of Ruanda-Urundi in 1923 and later a United Nations Trust Territory under Belgian administrative authority following World War II.

Twentieth century genocides

Since Burundi's independence in 1962, there have been three events labelled as genocide in the country.

1965: The demographics of Burundi through the 1960s and 1970s was roughly 80 percent Hutu, dominated by a small Tutsi minority. Burundi gained its independence in 1962, and in May 1965, the first post-independence elections were held. The Hutu candidates scored a landslide victory, capturing 23 seats out of a total 33. Instead of a Hutu prime minister being appointed, the king appointed a Tutsi to the position. In October of that year, the Hutus attempted a coup. The king fled the country, never to return, but the coup ultimately failed. The Tutsi-controlled army arrested and executed many leading Hutu civilian and military personalities, and continued to rule the country for the next 21 years.

1972: On April 29, 1972 an insurrection, led by some Hutu members of the gendarmerie, broke out in the lakeside towns of Rumonge and Nyanza-Lac. Countless atrocities were reported by eyewitnesses, and the armed Hutu insurgents proceeded to kill every Tutsi and Hutu moderate in sight. It is estimated that during this initial Hutu outbreak, anywhere from "2,000 to 3,000" people were killed. President Michel Micombero proclaimed martial law and systematically proceeded to slaughter Hutus en masse. The initial phases of the genocide were systematically orchestrated, with lists of targets including the Hutu educated, the elite, and the militarily trained. The Tutsi-controlled army then moved onto the larger civilian populations. The Tutsi-controlled government authorities originally estimated that roughly 15,000 had been killed while Hutu opponents claimed that the number was actually far closer to 300,000. Today, conservative estimates hover between these two figures, at 100,000 to 150,000 killed in a period of just over three months. Over five hundred thousand are estimated to have fled the genocide into Zaire, Rwanda, and Tanzania.

1993: In 1993, Burundi held its first democratic elections, which were won by the Hutu-dominated Front for Democracy in Burundi (FRODEBU). FRODEBU leader Melchior Ndadaye became Burundi's first Hutu president, but a few months later he was assassinated by a group of Tutsi army officers. The Hutu community responded violently to Ndadaye's assassination and it is estimated that possibly as many as twenty-five thousand Tutsi were killed. The Tutsi-dominated army responded by killing at least as many Hutu civilians. Burundi was plunged into a vicious civil war.

Today, the 1993 mass-killing of Tutsi is the only genocide officially acknowledged by the government. There is no official recognition of the Hutu victims of 1993, nor is there any recognition for the genocide of 1972. In effect, the genocide has been wiped from the official record, and forgotten by the international community in light of larger-scale genocides such as that of Rwanda.

Results: The genocide of 1972 left a permanent mark in the collective memory of the Hutu population, both in Burundi and in neighboring countries. Tens of thousands of Hutu civilians fled the country during the violence into their northern neighbor, Rwanda. The increased tensions in Burundi and Rwanda sparked episodes of civil and cross-border violence in Burundi which inevitably resulted in more large-scale killings by the Burundian army. These episodes further radicalized elements of the Hutu population in Rwanda who also faced pressure from a militant Tutsi opposition known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front. In 1994, a Hutu-led genocide was perpetrated in Rwanda which, along with the resulting civil war, claimed the lives of between seven hundred thousand and 1 million people.

Cease-fire

Instability followed until 1996, when former president Pierre Buyoya took power in a coup d'etat. In August 2000, a peace deal agreed by all but two of Burundi's political groups laid out a timetable for the restoration of democracy. After several more years of violence, a cease-fire was signed in 2003 between Buyoya's government and the largest Hutu rebel group, CNDD-FDD. Later that year, FRODEBU leader Domitien Ndayizeye replaced Buyoya as president. Yet the most extreme Hutu group, Palipehutu-FNL (commonly known as "FNL"), continued to refuse negotiations. In August 2004, the group massacred 152 Congolese Tutsi refugees at the Gatumba refugee camp in western Burundi. In response to the attack, the Burundian government issued arrest warrants for the FNL leaders and declared the group a terrorist organization.

In May 2005 a cease-fire was finally agreed on between the FNL and the Burundian government, but fighting continued. Renewed negotiations are now under way, amid fears that the FNL will demand a blanket amnesty in exchange for laying down their arms. A series of elections held in mid-2005 were won by the former Hutu rebel group CNDD-FDD. On September 7, 2006, a second cease-fire agreement was signed.

2006 to 2015

Reconstruction efforts in Burundi started to practically take effect after 2006. The UN shut down its peacekeeping mission and re-focused on helping with reconstruction.[6] Toward achieving economic reconstruction, Rwanda, D.R.Congo and Burundi relaunched the regional Economic Community of the Great Lakes Countries.[6] In addition, Burundi, along with Rwanda, joined the East African Community.

However, the terms of the September 2006 Ceasefire between the government and the last remaining armed opposition group, the FLN (Forces for National Liberation, also called NLF or FROLINA), were not totally implemented, and senior FLN members subsequently left the truce monitoring team, claiming that their security was threatened. In September 2007, rival FLN factions clashed in the capital, killing 20 fighters and causing residents to begin fleeing. Rebel raids were reported in other parts of the country.[6]

On April 17, 2008, the FLN bombarded Bujumbura. The Burundian army fought back and the FLN suffered heavy losses. A new ceasefire was signed on May 26, 2008. In August 2008, President Nkurunziza met with the FLN leader Agathon Rwasa, with the mediation of Charles Nqakula, South Africa's Minister for Safety and Security. In April 2009 the FNL officially became a political party in a ceremony supervised by the African Union.[6]

Refugee camps closed down and refugees have returned. The economy of the country was shattered leaving Burundi with one of the lowest per capita gross incomes in the world.

2015 unrest

In April 2015 protests broke out after the ruling party announced President Pierre Nkurunziza would seek a third term in office. Protestors claimed Nkurunziza could not run for a third term in office but the country's constitutional court agreed with the President (although some of its members had fled the country at the time of its vote).

An attempted coup d'état on 13 May failed to depose Nkurunziza. [7] Following the attempted coup, protests however continued and over 100,000 people had fled the country by May 20, causing a humanitarian emergency. There were reports of continued and widespread abuses of human rights, including unlawful killings, torture, disappearances, and restrictions on freedom of expression.

Despite calls by the United Nations, the African Union, the United States, France, South Africa, Belgium, and various other governments, the ruling party held parliamentary elections on June 29, but these were boycotted by the opposition.

The Commission of Inquiry

On September 30, 2016, the United Nations Human Rights Council established the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi through resolution 33/24. Its mandate is to "conduct a thorough investigation into human rights violations and abuses committed in Burundi since April 2015, to identify alleged perpetrators and to formulate recommendations."[8]

On September 29, 2017 the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi called on Burundian government to put an end to serious human rights violations. Following their investigation, the Commission reached the conclusion that "serious human rights violations and abuses have been committed in Burundi since April 2015. The violations the Commission documented include arbitrary arrests and detentions, acts of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, rape and other forms of sexual violence."[9]

Government

Burundi's political system is that of a presidential representative democratic republic based upon a multi-party state. The President of Burundi is the head of state and head of government.

Burundi's legislative branch is a bicameral assembly, consisting of the Transitional National Assembly and the Transitional Senate. Members of the National Assembly are elected by popular vote and serve five-year terms. The Transitional Senate has fifty-one members, and three seats are reserved for former presidents. Due to stipulations in Burundi's constitution, 30 percent of Senate members must be female. Members of the Senate are elected by electoral colleges, which consist of members from each of Burundi's provinces and communes.

Together, Burundi's legislative branch elect the President to a five-year term. Burundi's president appoints officials to his Council of Ministers, which is also part of the executive branch.

The Cour Suprême (Supreme Court) is Burundi's highest court. There are three Courts of Appeals directly below the Supreme Court. Tribunals of First Instance are used as judicial courts in each of Burundi's provinces as well as 123 local tribunals.

Geography

Burundi is a landlocked country with an equatorial climate. Called "The heart of Africa," Burundi lies on a rolling plateau, with Lake Tanganyika in its southwest corner. The average elevation of the central plateau is 5,600 feet, with lower elevations at the borders. The highest peak, Mount Karonje, at 8,809 feet (2,685 m), lies to the southeast of the capital, Bujumbura. The southeastern and southern borders are at roughly 4,500 feet (1,370 m). A strip of land along the Ruzizi River, north of Lake Tanganyika, is the only area below 3,000 feet (915 m); this area forms part of the Albertine Rift, the western extension of the Great Rift Valley. Because of its elevation, the nation's climate is temperate despite its proximity to the Equator, with the warmest and most humid area in the lowlands around Lake Tanganyika.

The land is mostly agricultural or pasture, the creation of which has led to deforestation, soil erosion, and habitat loss. Deforestation of the entire country is almost complete due to overpopulation, with a mere 60,000 hectares remaining and an ongoing loss of about nine percent per year. [10]

There are two national parks, Kibira National Park to the northwest (a small region of montane rainforest, adjacent to Nyungwe Forest National Park in Rwanda) and Rurubu National Park to the northeast (along the Rurubu River, also known as Ruvubu or Ruvuvu).

The farthest headstream of the Nile River is in Burundi. Although Lake Victoria is commonly considered the source of the Nile, the Kagera River flows for 429 miles (690 km) before reaching Lake Victoria. The source of the Ruvyironza River, an upper branch of the Kagera River, is at Mount Kikizi in Burundi.

Economy

Burundi is one of the poorest countries in the world, in terms of GDP per capita. The economy is supported by foreign aid from Western Europe and other parts of the world. It is a landlocked, resource-poor country with an underdeveloped manufacturing sector. The economy is predominantly agricultural, of which most is subsistence farming. Even though subsistence farming is highly relied upon, many people do not have the resources to sustain themselves.

Coffee is the nation's biggest revenue earner. Other agriculture products include cotton, tea, maize, sorghum, sweet potatoes, bananas (of which Burundi is one of the world's ten largest producers), manioc (tapioca); beef, milk, and hides. Besides agriculture, other industries include light consumer goods such as blankets, shoes, and soap; assembly of imported components; public works construction; and food processing.

Demographics

Roughly 85 percent of the population is of Hutu ethnic origin; most of the remaining population are Tutsi, with a minority of Twa (Pygmy), and a few thousand Europeans and South Asians. Many Burundians have migrated to other countries as a result of the civil war.

Less than half the children attend primary school, and a higher percentage of those who go to school are Tutsi. Few Hutu go on to secondary school. Both sides in the civil war used child soldiers.

The largest religion is Roman Catholicism, followed by indigenous beliefs and a minority of Protestants and Muslims (10 percent).

The official languages of Burundi are Kirundi, French, and, since 2014, English. Swahili can be found spoken along the Tanzanian border and it has some official recognition by law as a language "spoken and taught" in the country.

Culture

All Burundians enjoy music and dance. The Hutu use song for special occasions such as the birth of a child and harvesting crops, as well as for everyday events. The Tutsi also sing, with specific songs for activities in their lives such as feeding cattle. Dance, accompanied by drums, also serves ceremonial purposes. "The Master Drummers of Burundi" are the most famous performing group from the nation. Basket-weaving and pottery are crafts traditionally done by women for household use.

Soccer is the most popular sport.

Notes

- ↑ Oishimaya Sen Nag, What Languages Are Spoken In Burundi? World Atlas, August 1 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ CIA, Burundi World Factbook.

- ↑ Burundi Population and Housing Census 2008-2009 Global Health Data Exchange (GHDc), December 9, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Report for Selected Countries and Subjects - Burundi International Monetary Fund. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ GINI index World Bank. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Burundi profile - Timeline BBC. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Mind the coup The Economist, May 14, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Commission of Inquiry on Burundi United Nations Human Rights Council. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Commission calls on Burundian government to put an end to serious human rights violations United Nations Human Rights Council. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ United Nations Global rates of forest loss by country, Mongabay. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0521484227

- Kristine Brennan, Burundi, Broomall, PA: Mason Crest Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1590848209

- Charles H. Cutter, Africa: 2006, 41st ed., Harpers Ferry, WV: Stryker-Post Publications, 2006. ISBN 1887985727

- Totten, Samuel, William S. Parsons, and Israel W. Charny. Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views. New York: Garland Pub., 1997. ISBN 0815323530 and ISBN 9780815323532

External links

All links retrieved November 22, 2023.

- Country profile: Burundi BBC News

- U.S. Relations With Burundi U.S. Department of State

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.