Zen (禅), Japanese for "meditation," is a form of Mahāyāna Buddhism that stresses the practice of meditation as the key to enlightenment. It is characterized by mental discipline, calmness, austerities and effort. It can also be associated with koans, the Japanese tea ceremony and Zen gardens, depending on the sect involved.

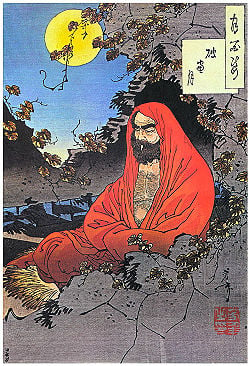

According to tradition, Zen originated in India as a non-verbal doctrine communicated directly by the Buddha to his followers. It was later taken to China by the monk Bodhidharma, where it was subsequently transmitted to other parts of Asia including Japan, China (Ch'an in Chinese), Vietnam (Thien) and Korea (Seon).

Though the Zen tradition has spawned numerous lineages, they all share two elements: a metaphysical system postulating that reality is essentially void and empty (sunyata) and the aforementioned stress on the practice of meditation.

Today, Zen is becoming increasingly popular in the West, where it is the most widely practiced sect of Buddhism among non-Asians. The popularity of Zen outside of Asia can perhaps be explained by the universality of its tenet that humbly emptying oneself leads one to go beyond oneself to be aware that all are interconnected, by its rejection of intellectualism that is refreshing in Western culture which makes high demands on the intellect at every moment, and by its simple and natural aesthetic.

History

Origins in India

According to legend, the beginnings of Zen can be traced back to the life of Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha. One day, the Buddha was asked to summarize his highest teachings in a simple and precise way. The Buddha replied to this request oddly by saying nothing and staying quiet. Simultaneously, he raised a flower in his hand and smiled at his disciples. It is said that one of his disciples, Mahakashapa, understood the Buddha's silence as a non-verbal (or mind-to-mind) transmission of advanced teachings only available to a select few. The sermon, often known as the "Flower Sermon," was the initial impetus and inspiration for the subsequent growth of Zen.

Development in China

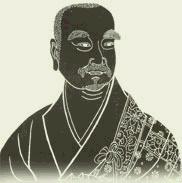

The establishment of the Ch’an school of Buddhism is traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma, who, according to legend, arrived in China sometime between 460 and 527 B.C.E.[1] Bodhidharma is recorded as having come to China to teach a "special transmission outside scriptures" which "did not rely upon words," which was then transmitted through a series of Chinese patriarchs, the most famous of whom was the Sixth Patriarch, Huineng. The sixth patriarch's importance is attested to in his (likely hagiographical) biography, which states that his virtue and wisdom were so great that Hongren (the fifth patriarch) chose him (a layman) over many senior monks as the next leader of the movement. This appointment led to seething jealousy and bitter recriminations among Hongren's students, which presaged a division between Huineng's followers and those of Hongren's senior pupil (Shenxiu). This rift persisted until the middle of the eighth century, with monks of Huineng's intellectual lineage, who called themselves the Southern school, opposing those followed Hongren's student Shenxiu (神秀). The Southern school eventually became predominant, which led to the eventual disintegration of competing lineages.

It should be noted that, despite the attribution of the tradition to an Indian monk, most scholars acknowledge that Ch’an was, in fact, an indigenous Chinese development that fused Daoist sensibilities with Buddhist metaphysics. As Wright argues:

…the distrust of words, the rich store of concrete metaphor and analogy, the love of paradox, the bibliophobia, the belief in the direct, person-to-person, and often world-less communication of insight, the feeling that life led in close communion with nature is conducive to enlightenment—all these are colored with Taoism. (Wright, 78; see also Ch'en, 213)

Further, since the tradition only entered the realm of fully documented history with the debates between the Southern school and the followers of Shenxiu, many Western scholars suggest that the early Zen patriarchs are better understood as legendary figures.

Regardless of these historical-critical issues, the centuries following the ascendance of the Southern school was marked by the Ch’an School’s growth into one of the largest sects of Chinese Buddhism. The teachers claiming Huineng's posterity began to branch off into numerous different schools, each with their own special emphases, but who all kept the same basic focus on meditational practice, individual instruction and personal experience. During the late Tang and the Song periods, the tradition truly flowered, as a wide number of eminent monks developed specialized teachings and methods, which, in turn, crystallized into the five houses (五家) of mature Chinese Zen: Caodong (曹洞宗), Linji (臨濟宗), Guiyang (潙仰宗), Fayan (法眼宗), and Yunmen (雲門宗). In addition to these doctrinal and pedagogical developments, the Tang period also saw a fruitful interaction between Ch’an (with its minimalistic and naturalistic tendencies) and Chinese art, calligraphy and poetry.

Over the course of Song Dynasty (960-1279), the Guiyang, Fayan, and Yunmen schools were gradually absorbed into the Linji. During the same period, Zen teaching began to incorporate an innovative and unique technique for reaching enlightenment: gong-an (Japanese: koan) practice (described below).[2] While koan practice was a prevalent form of instruction in the Linji school, it was also employed on a more limited basis by the Caodong school. The singular teachings of these Song-era masters came to be documented in various texts, including the Blue Cliff Record (1125) and The Gateless Gate (1228). Many of these texts are still studied today.

Ch’an continued to be an influential religious force in China, although some energy was lost to the syncretistic Neo-Confucian revival of Confucianism, which began in the Song period (960-1279). While traditionally distinct, Ch'an was taught alongside Pure Land Buddhism in many Chinese Buddhist monasteries. In time, much of this distinction was lost, and many masters taught both Ch’an and Pure Land. In the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), Ch’an Buddhism enjoyed something of a revival under luminaries such as Hanshan Deqing (憨山德清), who wrote and taught extensively on both Ch’an and Pure Land Buddhism; Miyun Yuanwu (密雲圓悟), who came to be seen posthumously as the first patriarch of the Obaku Zen school; as well as Yunqi Zhuhong (雲棲株宏) and Ouyi Zhixu (藕溢智旭).

After further centuries of decline, Ch’an was revived again in the early twentieth century by Hsu Yun, who stands out as the defining figure of twentieth-century Chinese Buddhism. Many well known Ch'an teachers today trace their lineage back to Hsu Yun, including Sheng-yen and Hsuan Hua, who have propagated Ch'an in the West where it has grown steadily through the twentieth and twenty-first century.

Ch’an was severely repressed in China with the appearance of the People's Republic, but has recently been reasserting itself on the mainland, and has a significant following in Taiwan and Hong Kong and among Chinese living abroad.[3]

Zen in Vietnam

Zen became an international phenomenon early in its history. After being brought to China, the Ch'an doctrines spread to Vietnam, whose traditions posit that in 580, an Indian monk named Vinitaruci (Vietnamese: Tì-ni-đa-lưu-chi) arrived in their country after completing his studies with Sengcan, the third patriarch of Chinese Zen. The school founded by Vinitaruci and his lone Vietnamese disciple is the oldest known branch of Vietnamese Zen (Thien (thiền) Buddhism).

By the tenth century (and after a period of obscurity), the Vinitaruci School became one of the most influential Buddhist groups in Vietnam, particularly so under the patriarch Vạn-Hạnh (died 1018). Other early Vietnamese Zen schools included the Vo Ngon Thong (Vô Ngôn Thông), which was associated with the teaching of Mazu (a famed Chinese master), and the Thao Duong (Thảo Đường), which incorporated nianfo chanting techniques; both were founded by itinerant Chinese monks. These three schools of early Thien Buddhism were profoundly disrupted by the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century, and the tradition remained nearly dormant until the founding of a new school by one of Vietnam's religious kings. This was the Truc Lam (Trúc Lâm) school, which evinced a deep influence from Confucian and Daoist philosophy. Nevertheless, Truc Lam's prestige waned over the following centuries as Confucianism became dominant in the royal court. In the seventeenth century, a group of Chinese monks led by Nguyen Thieu (Nguyên Thiều) established a vigorous new school, the Lam Te (Lâm Tế), which is the Vietnamese pronunciation of Linji. A more domesticated offshoot of Lam Te, the Lieu Quan (Liễu Quán) school, was founded in the eighteenth century and has since been the predominant branch of Vietnamese Zen.

Zen in Korea

China’s Ch’an Buddhism began to appear in Korea in the ninth century, with the first Korean practitioners traveling to China to study under the venerable Mazu (709-788). These pioneers had started a trend: over the next century, numerous Korean pupils studied under Mazu's successors, and some of them returned to Korea and established the Nine Mountain Schools. This was the beginning of Korean Zen (Seon). Among the most notable Seon masters were Jinul (1158-1210), who established a reform movement and introduced koan practice to Korea, and Taego Bou (1301-1382), who studied the Linji tradition in China and returned to unite the Nine Mountain Schools. In modern Korea, the largest Buddhist denomination is the Jogye Order, a Zen sect named after Huineng (the famed sixth Zen patriarch).

Zen in Japan

Although the Japanese had known of China's Ch’an Buddhism for centuries, it was not introduced as a separate school until the twelfth century, when Myōan Eisai traveled to China and returned to establish a Linji lineage, which is known in Japan as Rinzai. Decades later, Nanpo Jomyo (南浦紹明) also studied Linji teachings in China before founding the Japanese Otokan lineage, the most influential branch of Rinzai. In 1215, Dogen, a younger contemporary of Eisai's, journeyed to China himself, where he became a disciple of the Caodong master Tiantong Rujing. After his return, Dogen established the Soto school, the Japanese branch of Caodong. Over time, Rinzai came to be divided into several sub-schools, including Myoshin-ji, Nanzen-ji, Tenryū-ji, Daitoku-ji, and Tofuku-ji.

These sects represented the entirety of Zen in Japan until Ingen, a Chinese monk, founded the Obaku School in the seventeenth century. Ingen had been a member of the Linji School, the Chinese equivalent of Rinzai, which had developed separately from the Japanese branch for hundreds of years. Thus, when Ingen journeyed to Japan following the fall of the Ming Dynasty, his teachings were seen as representing a distinct and separate school. The Obaku School was named for Mount Obaku (Chinese: Huangboshan), which had been Ingen's home in China.

The three schools introduced above (Soto (曹洞), Rinzai (臨済), and Obaku (黃檗)) have all survived to the present day and are still active in the Japanese religious community. Of them, Soto is the largest and Obaku the smallest.

Zen Doctrine and Practice

Zen, in contrast to many other religions, as a means to deepen the practice could be seen as fiercely anti-philosophical, anti-prescriptive and anti-theoretical. Nonetheless, Zen is deeply rooted in both the teachings of the Buddha Siddhārtha Gautama and Mahāyāna Buddhist thought and philosophy.

One of the core Soto Zen practices is zazen, or seated meditation, and it recalls both the posture in which the Buddha is said to have achieved enlightenment under the Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya, and the elements of mindfulness and concentration which are part of the Eightfold Path as taught by the Buddha. All of the Buddha's fundamental teachings—among them the Eightfold Path, the Four Noble Truths, the idea of dependent origination, the "emptiness" (sunyata) of all phenomena, the five precepts, the five aggregates, and the three marks of existence—also make up important elements of the perspective that Zen takes for its practice.

Additionally, as a development of Mahāyāna Buddhism, Zen draws many of its basic driving concepts, particularly the bodhisattva ideal, from that school. Uniquely Mahāyāna figures such as Guān Yīn, Mañjuśrī, Samantabhadra, and Amitābha are venerated alongside the historical Buddha. Despite Zen's emphasis on transmission outside scriptures, it has drawn heavily on the Mahāyāna sūtras, particularly the Heart of Perfect Wisdom Sūtra, the Diamond Sutra, the Lankavatara Sūtra, and the "Samantamukha Parivarta" section of the Lotus Sūtra.

Zen has also itself paradoxically produced a rich corpus of written literature which has become a part of its practice and teaching. Among the earliest and most widely studied of the specifically Zen texts, dating back to at least the ninth century C.E., is the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, sometimes attributed to Huineng. Others include the various collections of kōans and the Shōbōgenzō of Dōgen Zenji.

Zen training emphasizes daily life practice, along with intensive periods of meditation. Practicing with others is an integral part of Zen practice. In explaining Zen Buddhism, Japanese Zen teachers have made the point that Zen is a "way of life" and not solely a state of consciousness. D. T. Suzuki wrote that aspects of this life are: a life of humility; a life of labor; a life of service; a life of prayer and gratitude; and a life of meditation.[4] The Chinese Ch'an master Baizhang Huaihai (720-814 C.E.) left behind a famous saying which had been the guiding principle of his life, "A day without work is a day without food."[5]

D. T. Suzuki asserted that satori (awakening) has always been the goal of every school of Buddhism, but that which distinguished the Zen tradition as it developed in China, Korea, and Japan was a way of life radically different from that of Indian Buddhists. In India, the tradition of the mendicant (bhikkhu) prevailed, but in China social circumstances led to the development of a temple and training-center system in which the abbot and the monks all performed mundane tasks. These included food gardening or farming, carpentry, architecture, housekeeping, administration, and the practice of folk medicine. Consequently, the enlightenment sought in Zen had to stand up well to the demands and potential frustrations of everyday life.

The Role of the "Master"

Because the Zen tradition emphasizes direct communication over scriptural study, direct person-to-person pedagogical interaction has always been of ultimate importance. Those who conduct this instruction are, generally speaking, people ordained in any tradition of Zen and authorized to perform rituals, teach the Dharma, and guide students in meditation.[6]

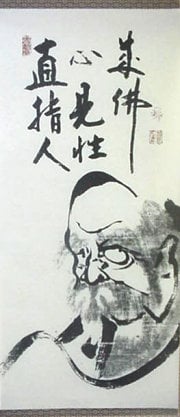

An important (and related) concept for all Zen sects in East Asia is the notion of Dharma transmission, the claim of a line of authority that goes back to the Buddha via the teachings of each successive master to each successive student. This concept relates to Bodhidharma's original depiction of Zen:

- A special transmission outside the scriptures; (教外別傳)

- No dependence upon words and letters; (不立文字)

- Direct pointing to the human mind; (直指人心)

- Seeing into one's own nature and attaining Buddhahood. (見性成佛)[7]

As a result of this, claims of Dharma transmission have been one of the normative aspects of all Zen sects. John McRae’s study Seeing Through Zen (2004) explores these lineage claims as a distinctive and central aspect of Zen Buddhism, and notes that they require a culturally-conservative, interpersonally-pedagogical teaching schema to be coherent. Intriguingly, this transmission history is seen as so important that it is common for daily chanting in Zen temples and monasteries to include the lineage of the school, in whole or in part, including a recitation of the names of all Dharma ancestors and teachers that have transmitted their particular Zen teaching.

In Japan during the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), some came to question the lineage system and its legitimacy. The Zen master Dokuan Genko (1630-1698), for example, openly questioned the necessity of written acknowledgment from a teacher, which he dismissed as "paper Zen." The only genuine transmission, he insisted, was the individual's independent experience of Zen enlightenment, an intuitive experience that needs no external confirmation. Occasional teachers in Japan during this period did not adhere to the lineage system; these were termed mushi dokugo (無師獨悟, "independently enlightened without a teacher") or jigo jisho (自悟自証, "self-enlightened and self-certified"). They were generally dismissed by established schools and, perhaps by necessity, left no independent transmission. Nevertheless, modern Zen Buddhists have continued to entertain questions about the dynamics of the lineage system, inspired in part by academic research into the history of Zen.

Zazen

The core of Zen practice, sitting meditation, is called zazen (坐禅). During zazen, practitioners usually assume a sitting position such as the lotus, half-lotus, Burmese, or seiza postures. Awareness is directed towards one's posture and breathing. Some small sectarian variations exist in certain practical matters: for example, in Rinzai Zen, practitioners typically sit facing the center of the room, while Soto practitioners traditionally sit facing a wall. Further, Soto Zen practice centers around shikantaza meditation ("just-sitting"), which is meditation with no objects, anchors, or content.[8] Conversely, Rinzai Zen emphasizes attention to the breath and koan practice.

The amount of time each practitioner spends in zazen varies. The generally acknowledged key, however, is daily regularity, as Zen teaches that the ego will naturally resist (especially during the initial stages of practice). Practicing Zen monks may perform four to six periods of zazen during a normal day, with each period lasting 30 to 40 minutes. Normally, a monastery will hold a monthly retreat period (sesshin), lasting between one and seven days. During this time, zazen is practiced more intensively: monks may spend four to eight hours in meditation each day, sometimes supplemented by further rounds of zazen late at night. Even householders are urged to spend at least five minutes per day in conscious and uninterrupted meditation.

Koan practice

For some Zen Buddhists, meditation practice centers around the use of koans: paradoxical sayings thought to provide keys to breaking down egoistic, dualistic thought. These koans (literally "public cases") may take the form of riddles or stories, which are generally related to Zen or other Buddhist history, with the most typical examples involving early Chinese Zen masters. Koan practice is particularly emphasized by the Chinese Linji and Japanese Rinzai schools, but it also occurs in other forms of Zen.

A koan is thought to embody a realized principle or law of reality, though they often appear to be paradoxical or linguistically meaningless sayings or questions. The 'answer' to the koan involves a transformation of perspective or consciousness, which may be either radical or subtle. In this way, they are tools that allow students to approach enlightenment by essentially 'short-circuiting' their learned, logical worldviews, forcing them to change their perspectives to accommodate these "paradoxical" utterances.

In addition to the private, meditational component of koan practice, it also involves active instruction, where the Zen student presents their solution to a given koan to the teacher in a private interview. There is a sharp distinction between right and wrong ways of answering a koan—although there may be many "right answers," practitioners are expected to demonstrate their understanding of the koan and of Zen through their answers. The teacher analyzes the pupil's response, and, if satisfactory, present them with a new problem, meant to further deepen their insights. In assigning these koans, Zen teachers advise that they are to be taken quite seriously and are to be approached as a matter of life and death.

While there is no single correct answer for any given koan, there are compilations of accepted answers to koans that serve as references for teachers. These collections are of great value to modern scholarship on the subject.

Zen in the Modern World

Japan

The fortunes of the Zen tradition in twentieth-century Japan have experienced some tumultuous vicissitudes. On one hand, the tradition has gained in intellectual rigor and international esteem (through the efforts of D. T. Suzuki and the Kyoto School). On the other, it has been critiqued for its involvement in "empty ritualism" and expansionistic Japanese militarism. It is essential to acknowledge both streams to get a clear picture of its modern fate.

One of the major influences behind the large-scale Western fascination with Zen (described below) was the availability of erudite and accessible scholarship relating to the tradition, in the form of translations, introductory books and scholarly essays. A large proportion of this scholarship can be credited to one man: D. T. Suzuki. A convert to Buddhism early in life, Suzuki's piercing intellect (and facility with languages) made him a logical candidate to translate various Zen Buddhist texts into English (and other European tongues), often making them available to a Western audience for the first time.

Later in life, D. T. Suzuki became a professor of Buddhist studies, producing accessible introductions to the tradition that were well received (both critically and popularly) in Japan and the West. A related group, known for their intellectual approach to Zen, is the Kyoto school: a loosely organized conclave of philosophers headquartered at Kyoto University. While the philosophers of the "school" shared certain commonalities (namely, an inherited Buddhist metaphysic centering on the concept of Nothingness (sunyata) and a respect for German philosophy), they were not bound by a ruling ideology or paradigm. Instead, they felt free to provide new interpretations of Japanese philosophy and Buddhism derived from these shared resources. Their various theories and perspectives continue to inform East/West philosophical and religious dialogue to this day, especially in academe.

Though Zen continues to thrive in contemporary Japan, it has not been without its critics. Some contemporary Japanese Zen teachers, such as Daiun Harada and Shunryu Suzuki, have attacked Japanese Zen as being a formalized system of empty rituals in which very few Zen practitioners ever actually attain realization (satori). They assert that almost all Japanese temples have become family businesses handed down from father to son, and that the Zen priest's function has largely been reduced to officiating at funerals.

Further, the Japanese Zen establishment—including the Soto sect, the major branches of Rinzai, and several renowned teachers—has been criticized for its involvement in Japanese militarism and nationalism during the years surrounding the Second World War, a phenomenon notably described in Zen at War (1998) by Brian Victoria, an American-born Soto priest.

Intriguingly, these critiques have made Japanese Zen more open and inclusive than ever before, allowing non-sectarian Buddhists, non-Buddhists and even Christians to involve themselves in Zen praxis. This spirit of inclusiveness and inter-religious dialogue was likely one of the motivating factors behind the large-scale importation of Zen into North America.

Zen in the Western world

The visit of Soyen Shaku, a Japanese Zen monk, to Chicago during the World Parliament of Religions in 1893 raised the profile of Zen in the Western world. However, it was not until the late 1950s and the early 1960s that a significant number of Westerners (other than the descendants of Asian immigrants) began seriously pursuing Zen teachings.

The American occupation of Japan following the Second World War led to greater exposure of U.S. servicemen and women to Japanese culture and the ideas of Zen. These military personnel returned to America with a new awareness and respect for Zen, which some incorporated in their daily lives. Thus, Zen ideas began to percolate into U.S. consciousness and popular culture.

Zen started to show up in the poetry and writing of the "Beat Zen" movment. In particular, The Dharma Bums, a novel written by Jack Kerouac and published in 1959, detailed the fascination of bohemian American youths with Buddhism and Zen.

In addition to these authors, some Roman Catholic scholars began to take and interest in Zen in the spirit of interreligious dialogue. In particular, Thomas Merton (1915-1968), a Trappist monk and priest [9] was a central figure in the development of dialogue between Christian and Buddhist monastics. This spirit is exemplified in his dialogue with D. T. Suzuki, which explores the many congruencies between Christian mysticism and Zen.[10]

Growing Western interest in Zen was not limited to America. The European expressionist and Dada movements in art discovered that they had much in common with the study of Zen. This connection is demonstrated by the early French surrealist René Daumal, who translated D. T. Suzuki as well as Sanskrit Buddhist texts.

The British-American philosopher Alan Watts took a close interest in Zen Buddhism, writing and lecturing extensively on it during the 1950s. He understood it as a vehicle for a mystical transformation of consciousness, and also as a historical example of a non-Western, non-Christian way of life that had fostered both the practical and fine arts.

Western Zen lineages

Over the last 50 years, mainstream forms of Zen, led by teachers who trained in East Asia and by their successors, have begun to take root in the West. In North America, the most prevalent are Zen lineages derived from the Japanese Soto School. Among these are the lineage of the San Francisco Zen Center, established by Shunryu Suzuki; the White Plum Asanga, founded by Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi; Big Mind, founded by Dennis Genpo Merzel; the Ordinary Mind school, founded by Joko Beck, one of Maezumi's heirs; the International Zen Association, founded by Taisen Deshimaru (a student of Kodo Sawaki); and the Katagiri lineage, founded by Dainin Katagiri, which has a significant presence in the Midwestern United States. Note that both Taizan Maezumi and Dainin Katagiri served as priests at Zenshuji Soto Mission in the 1960s.

There are also a number of Rinzai Zen centers in the West, such as the Rinzaiji lineage of Kyozan Joshu Sasaki and the Dai Bosatsu lineage established by Eido Shimano.

Another group that has significantly influenced the development of Zen Buddhism in the West is Sanbo Kyodan, a Japan-based reformist Zen group founded in 1954 by Yasutani Hakuun. Their approach is primarily based on the Soto tradition, but also incorporates Rinzai-style koan practice. One of the reasons for this sect's influence is that it was explored in Philip Kapleau's popular book The Three Pillars of Zen (1965), which was one of the first sources to introduce Western audiences to the actual practice of Zen (rather than its philosophy).

It should be noted that not all the successful Zen teachers in the West have emerged from Japanese traditions. There have also been teachers of Ch’an, Seon, and Thien Buddhism.

For example, a famous Chinese Buddhist priest was Hsuan Hua, who taught Westerners about Chinese Pure Land, Tiantai, Vinaya, and Vinayana Buddhism in San Francisco during the early 1960s. He went on to found the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, a monastery and retreat center located on a 237-acre (959,000 square meters) property near Ukiah, California.

Another Chinese Zen teacher with a Western following is Sheng-yen, a master trained in both the Caodong and Linji schools (equivalent to the Japanese Soto and Rinzai, respectively). He first visited the United States in 1978 under the sponsorship of the Buddhist Association of the United States, and, in 1980, founded the Ch’an Mediation Society in Queens, New York.

The most prominent Korean Zen teacher in the West was Seung Sahn. Seung Sahn founded the Providence Zen Center in Providence, Rhode Island, which was to become the headquarters of the Kwan Um School of Zen, a large international network of affiliated Zen centers.

Two notable Vietnamese Zen teachers have been influential in Western countries: Thich Thien-An and Thich Nhat Hanh. Thich Thien-An came to America in 1966 as a visiting professor at the University of California-Los Angeles and taught traditional Thien meditation. Thich Nhat Hanh was a monk in Vietnam during the Vietnam War, during which time he was a peace activist. In response to these activities, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967 by Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1966 he left Vietnam in exile and now resides at Plum Village, a monastery in France. He has written more than one hundred books about Buddhism, making him one of the most prominent Buddhist authors among the general readership in the West. In his books and talks, Thich Nhat Hanh emphasizes mindfulness (sati) as the most important practice in daily life.

Universality of Zen

Although Zen has particularistic elements in its affirmation of Buddhist orthodoxy,[11] nevertheless the fact that it has been welcomed to the Western world is an indication of its universal appeal. Zen meditation has practical value, promoting centeredness and poise in one's daily activities. By emptying oneself in meditation, one can be free from selfish attachment and clinging, and able to face people and events with calmness and wisdom.

The Zen state of emptiness is not alien to Christianity in the West, which has long taught the importance of humility in front of divine grace. The New Testament teaches the way of kenosis (self-emptying) as was shown by Christ (Philippians 2:7). Unlike Zen in the East, however, the West has long been inclined to affirm the priority of the independent identity of each being, thus also making a sharp distinction between God and the world.

The Western emphasis on the self is now seen by many as destructive. Particularly with the rise of ecological thinking, it is becoming evident that human self-aggrandizement, expressed through excessive consumption, is damaging the environment. The ecological standpoint, which views the whole earth as a living organism (Gaia), a community of relationships that flourishes through mutual interaction. This new awareness is largely in agreement with the spirit of Zen. Zen practice, which cultivates a strong sense of interconnectedness of reality and the "emptiness" (sunyata) of self, can thus be of great benefit in aligning humanity with needs of the planet.

Among scientists who study quantum physics, with its theories of the duality of particle and wave and its Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle declaring the indeterminacy of existence, Richard Feynman has remarked that the mind of Zen provides a good doorway into the comprehension of these theories.

Notes

- ↑ The earlier date is from the (near) contemporary text The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks (645 C.E.), while the later is found in the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (952 C.E.). Both of these accounts can be found in Jeffrey Broughton's The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999).

- ↑ For more on the history and development of the koan, see Miura and Sasaki.

- ↑ This section contains some text from the Wikipedia article on "Chan," available under the GNUFDL license.

- ↑ Daisetz T. Suzuki. The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk. (Tokyo: Cosimo, Inc., 2004. ISBN 1596050411).

- ↑ 'Baizhang Huaihai," in Digital Dictionary of Buddhism. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ↑ Note: These instructors are often termed Zen master in English-language source. However, there is no specific criterion by which one may be called a Zen master. As a result, the term is less common in reference to modern teachers.

- ↑ Albert Welter, The Disputed Place of "A Special Transmission" Outside the Scriptures in Ch'an. accessdate June 23, 2006

- ↑ Considerable textual, philosophical, and phenomenological justification for this practice can be found in Dogen's Shobogenzo.

- ↑ Thomas Merton, Life and Work. Trappist monk and priest. Bellarmine University merton.org. Retrieved August 28, 2008

- ↑ Thomas Merton, "Wisdom in Emptiness" in Zen and the Birds of Appetite. (New York: New Directions, 1968)

- ↑ Benjamin Radcliff and Amy Radcliff. Understanding Zen. (Tuttle Publishing, 1993).

Bibliography

- Broughton, Jeffrey (trans.). The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999.

- Ch'en, Kenneth. Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1972.

- Dogen (1200-1253). A Complete Translation of Dogen Zenji's Shobogenzo (The Eye and Treasury of the True Law). Tokyo: Nakayama Shobo; San Francisco, CA: Japan Publications Trading Co., 1975-1983.

- Herrigel, Eugen (with an introduction by D. T. Suzuki). Zen in the Art of Archery. New York: Vintage Books, 1999. ISBN 0375705090

- McRae, John R. Seeing through Zen: Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004.

- Merton, Thomas. "Wisdom in Emptiness" in Zen and the Birds of Appetite. New York: New Directions, 1968.

- Miura, Isshu, and Ruth Fuller Sasaki. Zen dust: The History of the Koan and Koan Study in Rinzai (Lin-chi) Zen. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967.

- Kodera, Takashi James. Dogen's Formative Years in China: An Historical Study and Annotated Translation of the H¯oky¯o-ki. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980.

- Radcliff, Benjamin, and Amy Radcliff, Understanding Zen. Tuttle Publishing, 1993.

- Suzuki, Daisetz T. The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk. Tokyo: Cosimo, Inc., 2004. ISBN 1596050411

- Victoria, Brian Daizen. Zen at War, 2nd Edition. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2006. ISBN 0742539261

- Wei, Wei Wu. Why Lazarus Laughed: The Essential Doctrine Zen-Advaita-Tantra. Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., London, 1960. Selections available online here.

- Wright, Arthur F. Buddhism in Chinese History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959.

External Links

All links retrieved June 13, 2023.

- Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Zen Guide: Comprehensive Guide to Zen and Buddhism – Principles, practice guides, active discussion forum, organization directory, full text of key Sutras and other books

- The International Research Institute for Zen Buddhism

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.