Charles II of England

| Charles II | ||

|---|---|---|

| King of Scots, King of England, and King of Ireland | ||

| ||

| Reign | May 29, 1660–February 6, 1685 (de jure king from January 30, 1649–May 29, 1660) | |

| Born | May 29, 1630 | |

| St. James's Palace | ||

| Died | February 6, 1685 | |

| Buried | Westminster Abbey | |

| Predecessor | Richard Cromwell (de facto) Charles I (de jure) | |

| Successor | James II | |

| Consort | Catherine of Braganza | |

| Royal House | Stuart | |

| Father | Charles I | |

| Mother | Henrietta Maria | |

Charles II (May 29, 1630 – February 6, 1685) was the King of England, King of Scots, and King of Ireland from January 30, 1649 (de jure) or May 29, 1660 (de facto) until his death. His father Charles I had been executed in 1649, following the English Civil War; the monarchy was then abolished and England, and subsequently Scotland and Ireland, became a united republic under Oliver Cromwell, the Lord Protector (see Commonwealth of England and The Protectorate), albeit with Scotland and Ireland under military occupation and de facto martial law. In 1660, shortly after Cromwell's death, the monarchy was restored under Charles II. He was popularly known as the "Merry Monarch" in reference to the liveliness and hedonism of his court.

The exact date that Charles became king is vague due to the uncertain political situation of the time. His father was executed on January 30, 1649, making him in theory King Charles II from that moment. He was immediately proclaimed king in Scotland on February 5 and Jersey on February 16, 1649, but was also recognized in a few British colonies (especially the Colony and Dominion of Virginia). In Scotland Charles was for some time king in title only. It took two years of negotiation with the Presbyterians before he was finally crowned King of Scots in Scone on January 1, 1651. However, his reign there was short lived as he was soon driven out by the republican armies, led by Oliver Cromwell. His coronation in England would not be until after Cromwell's death and the monarchy's restoration in May 1660; Charles spent most of the intervening time exiled in France.

Much like his father, Charles II struggled for most of his life in his relations with Parliament, although the tensions between the two never reached the same levels of hostility. He was only able to achieve true success toward the end of his reign, by dispensing with Parliament and ruling alone. Unlike his father's policy, however, this policy did not lead to widespread popular opposition, as he avoided the imposition of any new taxes, thanks in part to money he received as a result of his close relationship with the French king, Louis XIV. The principal conflicts of his reign revolved around a number of interlinked issues in domestic and foreign policy, most of which were related to the conflict between Protestants and Catholics then raging across Europe. As a consequence of this, Charles's reign was racked by political factions and intrigue, and it was at this time that the Whig and Tory political parties first developed.

Charles II famously fathered numerous illegitimate children, of whom he acknowledged 14, but no legitimate children who lived. Charles was also a patron of the arts, and he and his court were largely responsible for the revival of public drama and music known as the Restoration literature, after their virtual prohibition under the earlier Protectorate. Some historians, such as Maurice Ashley, believe that Charles was secretly a Roman Catholic for much of his life like his brother James while others, such as Antonia Fraser, disagree. All that is known for certain is that he had converted to Roman Catholicism by the time of his death.

Early Life

Charles, the eldest surviving son of Charles I of England and Henrietta Maria of France, was born Charles Stuart in St. James's Palace on May 29, 1630. At birth, he automatically became (as the eldest surviving son of the Sovereign) Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay; shortly after his birth, he was crowned Prince of Wales. Due to the disruption caused by the English Civil War, he was never formally invested with the Honors of the Principality of Wales.

| British Royalty |

|---|

| House of Stuart |

|

| Charles II |

| Illegitimate sons included |

| James Scott, Duke of Monmouth |

| Charles FitzRoy, Duke of Cleveland and Southampton |

| Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Grafton |

| George FitzRoy, Duke of Northumberland |

| Charles Beauclerk, Duke of St Albans |

| Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond and Lennox |

During the 1640s, when the Prince of Wales was still young, his father Charles I fought Parliamentary and Puritan forces in the English Civil War. The prince accompanied his father during the Battle of Edgehill and, at the age of 15, participated in the campaigns of 1645, when he was made titular commander of the English forces in the West Country. In 1647, due to fears for his safety, he left England, going first to the Isles of Scilly, then to Jersey, and finally to France, where his mother was already living in exile. (His cousin, Louis XIV sat on the French throne.) In 1648, during the Second Civil War, Charles moved to The Hague, where his sister Mary and his brother-in-law Prince of Orange seemed more likely to provide substantial aid to the Royalist cause than the Queen's French relations. However, Charles was neither able to use the Royalist fleet that came under his control to any advantage, nor to reach Scotland in time to join up with the Royalist "Engagers" army of the Duke of Hamilton before it was defeated at the Battle of Preston.

At The Hague, Charles II had an affair with Lucy Walter (whom, some alleged, he secretly married). Their son, James Crofts (afterward Duke of Monmouth and Duke of Buccleuch), was to become the most prominent of Charles's many illegitimate sons in English political life, and famously led a rebellion on Charles's death, aimed at placing himself (a staunch Protestant) on the throne instead of Charles's Catholic brother James.

Charles I was captured in 1647. He escaped and was recaptured in 1648. Despite his son's efforts to save him, Charles I was executed in 1649, and England was proclaimed a republic.

At the same time, however, Scotland recognized Charles as his father's successor—even the Covenanters (led by the Archibald Campbell, Marquess of Argyll), the most extreme Presbyterian group in Scotland, proved unwilling to allow the English to decide the fate of their monarchy. Consequently, on February 5, 1649, Charles II was proclaimed King of Scots in Edinburgh. He would not be allowed to enjoy the powers that followed from his title until such time as he signed the Solemn League and Covenant (an agreement between England and Scotland that the Church of Scotland should not be remodeled on Anglican lines but should remain Presbyterian—the form of church governance preferred by most in Scotland—and that the Church of England and the Church of Ireland should be reformed along the same lines) (see also Treaty of Breda (1650)). Upon his arrival in Scotland on June 23, 1650, he formally agreed to the Covenant; his abandonment of Anglicanism, although winning him support in Scotland, left him unpopular in England. Charles himself soon came to despise his Scottish hosts (or "gaolers," as he came to see the dour Covenanters), and supposedly celebrated at the news of the Covenanters' defeat at the Battle of Dunbar in September 1650. Nevertheless, the Scots remained Charles's best hope of restoration, and he was crowned King of Scots at Scone, Perthshire on January 1, 1651. With Oliver Cromwell's forces threatening Charles's position in Scotland, it was decided that an attack should be mounted on England. With many of the Scots (including Argyll and other leading Covenanters) refusing to participate, and with few English Royalists joining the force as it moved south into England, the invasion ended in defeat at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651, following which Charles is said to have hidden in the Royal Oak Tree at Boscobel House, subsequently escaping to France in disguise. Parliament put a reward of £1,000 on the king's head, and the penalty of death for anyone caught helping him. Through six weeks of narrow escapes Charles managed to flee England.

Impoverished, Charles could not obtain sufficient support to mount a serious challenge to Cromwell's government. Despite the Stuart familial connections through Henrietta Maria and the Princess of Orange, France and the United Provinces allied themselves with Cromwell's government, forcing Charles to turn to Spain for aid. He attempted to raise an army, but failed due to his financial shortcomings.

Restoration

After the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658, Charles's chances of regaining the Crown seemed slim. Oliver Cromwell was succeeded as Lord Protector by his son, Richard Cromwell. However, the new Lord Protector, with no power base in either Parliament or the New Model Army, was forced to abdicate in 1659. The Protectorate of England was abolished, and the Commonwealth of England re-established. During the civil and military unrest that followed, George Monck, the Governor of Scotland, was concerned that the nation would descend into anarchy. Monck and his army marched into the City of London and forced the Long Parliament to dissolve itself. For the first time in almost 20 years, the members of Parliament faced a general election.

A predominantly Royalist House of Commons was elected. Soon after it assembled on April 25, 1660, the Convention Parliament received news of the Declaration of Breda (May 8, 1660), in which Charles agreed, among other things, to pardon many of his father's enemies. It also subsequently declared that Charles II had been the lawful Sovereign since Charles I's execution in 1649.

Charles set out for England, arriving in Dover on May 23, 1660 and reaching London on May 29, which is considered the date of the Restoration, and was Charles's 30 birthday. Although Charles granted amnesty to Cromwell's supporters in the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion, this made specific provision for people to be excluded by the indemnity through act of Parliament. In the end 13 people were executed: they were hanged, drawn, and quartered; others were given life imprisonment or simply excluded from office for life. The bodies of Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, and John Bradshaw were subjected to the indignity of posthumous executions.

Cavalier Parliament

The Convention Parliament was dissolved in December 1660. Shortly after Charles's coronation at Westminster Abbey on April 23, 1661, the second Parliament of the reign—the Cavalier Parliament—assembled. As the Cavalier Parliament was overwhelmingly Royalist, Charles saw no reason to dissolve it and force another general election for 17 years.

The Cavalier Parliament concerned itself with the agenda of Charles's chief advisor, Lord Clarendon (Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon). Lord Clarendon sought to discourage non-conformity to the Church of England; at his instigation, the Cavalier Parliament passed several acts that became part of the "Clarendon Code." The Conventicle Act of 1664 prohibited religious assemblies of more than five people, except under the auspices of the Church of England. The Five Mile Act of 1665 prohibited clergymen from coming within five miles of a parish from which they had been banished. The Conventicle and Five Mile Acts remained in effect for the remainder of Charles's reign. Other parts of the Clarendon Code included the Corporation Act of 1661 and the Act of Uniformity of 1662.

Charles agreed to give up antiquated feudal dues which had been revived by his father; in return, he was granted an annual income of £1,200,000 by Parliament. The grant, however, proved to be of little use for most of Charles's reign. The aforesaid sum was only an indication of the maximum the king was allowed to withdraw from the Treasury each year; for the most part, the amount actually in the coffers was much lower. To avoid further financial problems, Charles appointed George Downing (the builder of Downing Street) to reform the management of the Treasury and the collection of taxes.

Foreign Policy

In 1662 Charles married a Portuguese princess, Catherine of Braganza, who brought him the territories of Bombay and Tangier as dowry. During the same year, however, he sold Dunkirk—a much more valuable strategic outpost—to his first cousin, King Louis XIV of France, for £40,000.

Appreciative of the assistance given to him in gaining the throne, Charles awarded North American lands then known as the Carolina—named after his father—to eight nobles (known as Lords Proprietors) in 1663.

The Navigation Acts (1650), which hurt Dutch trade and started the First Dutch War (1652-1654), were also responsible for starting the Second Dutch War (1665-1667). This conflict began well for the English, with the capture of New Amsterdam (later renamed New York in honor of Charles's brother James, Duke of York, the future James II of England/James VII of Scotland), but in 1667 the Dutch launched a surprise attack upon the English (the Raid on the Medway) when they sailed up the River Thames to where the better part of the English Fleet was docked. Almost all of the ships were sunk except for the flagship, the Royal Charles, which was taken back to the Netherlands as a trophy. The ship's nameplate remains on display, now at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. The Second Dutch War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Breda in 1667.

As a result of the Second Dutch War, Charles dismissed his advisor Lord Clarendon, whom he used as a scapegoat for the war. Clarendon fled to France when impeached by the House of Commons for high treason, which carried the penalty of death. Power passed to a group of five politicians known as the Cabal—Thomas Clifford, 1st Baron Clifford, Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington, George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley (afterwards Earl of Shaftesbury), and John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale.

In 1668 England allied itself with Sweden and its former enemy the Netherlands in order to oppose Louis XIV in the War of Devolution. Louis was forced to make peace with the Triple Alliance, but he continued to maintain his aggressive intentions. In 1670 Charles, seeking to solve his financial troubles, agreed to the Treaty of Dover, under which Louis XIV would pay him £200,000 each year. In exchange, Charles agreed to supply Louis with troops and to convert himself to Roman Catholicism "as soon as the welfare of his realm will permit." Louis was to provide him with six thousand troops with which to suppress those who opposed the conversion. Charles endeavored to ensure that the Treaty—especially the conversion clause—remained secret. It remains unclear if Charles ever seriously intended to follow through with the conversion clause.

Meanwhile, by a series of five acts around 1670, Charles granted the British East India Company the rights to autonomous territorial acquisitions, to mint money, to command fortresses and troops, to form alliances, to make war and peace, and to exercise both civil and criminal jurisdiction over the acquired areas in India. Earlier in 1668 he leased the islands of Bombay for a paltry sum of ten pounds sterling paid in gold.[1]

Great Plague and Fire

In 1665, Charles II was faced with a great health crisis: an outbreak of Bubonic Plague in London commonly referred to as the Great Plague. Believed to have been introduced by Dutch shipping vessels carrying cotton from Amsterdam, the plague was carried by rats and fleas and the death toll at one point reached up to seven thousand per week. Charles, his family, and his court fled London in July 1665 to Oxford. Various attempts at containing the disease by London public health officials were all in vain and the disease continued to spread rapidly.

On September 2, 1666, adding to London's woes, was what later became famously known as the Great Fire of London. Although effectively ending the spreading of the Great Plague due to the burning of all plague-carrying rats and fleas, the fire consumed about 13,200 houses and 87 churches, including St. Paul's Cathedral. Charles II is famously remembered for joining the fire-fighters in combating the fire.

At the time, a comet was visible in the night sky. The supposition of the day claimed it was God's message, and that the above crises were as a result of God's anger. Blame was placed upon Charles and his Court, but later the people shifted their blame to the hated Roman Catholics. The situation was not helped by Charles's brother, James II's conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1667.

Conflict with Parliament

Although previously favorable to the Crown, the Cavalier Parliament was alienated by the king's wars and religious policies during the 1670s. In 1672 Charles issued the Royal Declaration of Indulgence, in which he purported to suspend all laws punishing Roman Catholics and other religious dissenters. In the same year, he openly supported Catholic France and started the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

The Cavalier Parliament opposed the Declaration of Indulgence on constitutional grounds, claiming that the king had no right to arbitrarily suspend laws, rather than on political ones. Charles II withdrew the Declaration, and also agreed to the Test Act, which not only required public officials to receive the sacrament under the forms prescribed by the Church of England, but also forced them to denounce certain teachings of the Roman Catholic Church as "superstitious and idolatrous." The Cavalier Parliament also refused to further fund the Anglo-Dutch War, which England was losing, forcing Charles to make peace in 1674.

Charles's wife Queen Catherine was unable to produce an heir, her pregnancies instead ending in miscarriages and stillbirths. Charles's heir-presumptive was therefore his unpopular Roman Catholic brother, James, Duke of York. In 1678 Titus Oates, a former Anglican cleric, falsely warned of a "Popish Plot" to assassinate the king and replace him with the Duke of York. Charles did not believe the allegations, but ordered his chief minister Thomas Osborne, 1st Earl of Danby to investigate. Danby was highly skeptical about Oates's revelations, but reported the matter to Parliament. The people were seized with an anti-Catholic hysteria; judges and juries across the land condemned the supposed conspirators; numerous innocent individuals were executed.

Later in 1678 Lord Danby was impeached by the House of Commons on the charge of high treason. Although much of the nation had sought war with Catholic France, Charles II had secretly negotiated with Louis XIV, trying to reach an agreement under which England would remain neutral in return for money. Lord Danby was hostile to France, but reservedly agreed to abide by Charles's wishes. Unfortunately for him, the House of Commons failed to view him as a reluctant participant in the scandal, instead believing that he was the author of the policy. To save Lord Danby from the impeachment trial in the House of Lords, Charles dissolved the Cavalier Parliament in January 1679.

A new Parliament, which met in March of the same year, was quite hostile to the king. Lord Danby was forced to resign the post of Lord High Treasurer, but received a pardon from the king. In defiance of the royal will, Parliament declared that dissolution did not interrupt impeachment proceedings. When the House of Lords seemed ready to impose the punishment of exile—which the House of Commons thought too mild—the impeachment was abandoned, and a bill of attainder introduced. As he had had to do so many times during his reign, Charles II bowed to the wishes of his opponents, committing Lord Danby to the Tower of London. Lord Danby would be held without bail for another five years.

Later Years

Another political storm that faced Charles was that of succession to the Throne. The Parliament of 1679 was vehemently opposed to the prospect of a Catholic monarch. Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury (previously Baron Ashley and a member of the Cabal, which had fallen apart in 1672) introduced the Exclusion Bill, which sought to exclude the Duke of York from the line of succession. Some even sought to confer the Crown to the Protestant Duke of Monmouth, the eldest of Charles's illegitimate children. The "Abhorrers"—those who opposed the Exclusion Bill—would develop into the Tory Party, while the "Petitioners"—those who supported the Exclusion Bill—became the Whig Party.

Fearing that the Exclusion Bill would be passed, Charles dissolved Parliament in December 1679. Two further Parliaments were called in Charles's reign (one in 1680, the other in 1681), but both were dissolved because they sought to pass the Exclusion Bill. During the 1680s, however, popular support for the Exclusion Bill began to dissolve, and Charles experienced a nationwide surge of loyalty, for many of his subjects felt that Parliament had been too assertive. For the remainder of his reign, Charles ruled as an absolute monarch.

Charles's opposition to the Exclusion Bill angered some Protestants. Protestant conspirators formulated the Rye House Plot, a plan to murder the King and the Duke of York as they returned to London after horse races in Newmarket. A great fire, however, destroyed much of Newmarket and caused the cancellation of the races; thus, the planned attack could not take place. Before news of the plot leaked, the chief conspirators fled. Protestant politicians such as Algernon Sydney and the Lord William Russell were implicated in the plot and executed for high treason, albeit on very flimsy evidence.

Charles suffered an apopleptic fit and died suddenly on Wednesday, February 6, 1685 (at the age of 54) at 11:45am at Whitehall Palace of uremia (a clinical syndrome due to kidney dysfunction). He is purported to have said to his brother, the Duke of York, on his deathbed: “Let not poor Nelly starve.” and to his courtiers: “I am sorry, gentlemen, for being such a time a-dying.”[2] He was buried in Westminster Abbey “without any manner of pomp” and was succeeded by his brother who became James II of England and Ireland, and James VII of Scotland.[3]

Posterity and Legacy

Charles II left no legitimate issue. He did, however, have several children by a number of mistresses (many of whom were wives of noblemen). Many of his mistresses and illegitimate children received dukedoms or earldoms. He publicly acknowledged 14 children by seven mistresses; six of those children were borne by a single woman, the notorious Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine, for whom the Dukedom of Cleveland was created. His other favorite mistresses were Nell Gwynne and Louise Renée de Penancoët de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth. Charles also acknowledged children by Lucy Walter, Elizabeth Killigrew, Viscountess Shannon, and Catherine Pegge, Lady Greene. The present Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, Duke of Richmond and Gordon, Duke of Grafton, and Duke of St. Albans all descend from Charles in direct male line. Charles's relationships, as well as the politics of his time, are depicted in the historical drama Charles II: The Power and The Passion (produced in 2003 by the British Broadcasting Corporation).

Diana, Princess of Wales was descended from two of Charles's illegitimate sons, the Duke of Grafton and the Duke of Richmond (who is also a direct ancestor of Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, second wife of Charles, Prince of Wales). Thus Diana's son Prince William of Wales, currently second in line to the British Throne, is likely to be the first monarch descended from Charles I since Queen Anne.

Charles II's eldest son, the Duke of Monmouth, led a rebellion against James II, but was defeated at the battle of Sedgemoor on July 6, 1685, captured, and executed. James II, however, was eventually dethroned in 1688 in the course of the Glorious Revolution. James was the last Catholic monarch to rule England.

Charles, a patron of the arts and sciences, helped found the Royal Society, a scientific group whose early members included Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle, and Sir Isaac Newton. Charles was the personal patron of Sir Christopher Wren, the architect who helped rebuild London after the Great Fire in 1666. Wren also constructed the Royal Hospital Chelsea, which Charles founded as a home for retired soldiers in 1681. Since 1692, a statue of Charles II in ancient Roman dress (created by Grinling Gibbons in 1676) has stood in the Figure Court of the Royal Hospital.

The anniversary of Charles's Restoration (which is also his birthday)—May 29—is recognized in the United Kingdom as "Oak Apple Day," after the Royal Oak in which Charles is said to have hidden to escape from the forces of Oliver Cromwell. Traditional celebrations involved the wearing of oak leaves, but these have now died out. The anniversary of the Restoration is also an official Collar Day.

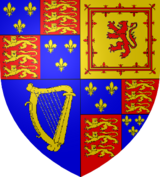

Style and Arms

The official style of Charles II was "Charles the Second, by the Grace of God, King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, etc." The claim to France was only nominal, and had been asserted by every English King since Edward III, regardless of the amount of French territory actually controlled. His arms were: Quarterly, I and IV Grandquarterly, Azure three fleurs-de-lis Or (for France) and Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or (for England); II Or a lion rampant within a tressure flory-counter-flory Gules (for Scotland); III Azure a harp Or stringed Argent (for Ireland).

Ancestors

| Charles II of England | Father: Charles I of England |

Paternal Grandfather: James I of England |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Mary I of Scotland | |||

| Paternal Grandmother: Anne of Denmark |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Frederick II of Denmark | ||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Sofie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin | |||

| Mother: Henrietta Maria of France |

Maternal Grandfather: Henry IV of France |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Antoine of Navarre | |

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Jeanne III of Navarre | |||

| Maternal Grandmother: Marie de' Medici |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Francesco I de' Medici | ||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Johanna of Austria |

The Children of Charles II

Charles left no legitimate heirs, but fathered an unknown number of illegitimate children. He acknowledged 14 children to be his own, including Barbara Fitzroy, who almost certainly was not his child.

- By Marguerite or Margaret de Carteret

- Some accounts say that she bore Charles a son named James de la Cloche in 1646. James de Carteret/de la Cloche is believed to have died sometime around the year 1667.

- By Lucy Walter (1630–1658)

- James Crofts "Scott" (1649–1685), created Duke of Monmouth (1663) in England and Duke of Buccleuch (1663) in Scotland. Ancestor of Sarah, Duchess of York.

- Mary Crofts (born c. 1651–?), not acknowledged. She married a William Sarsfield and later a William Fanshaw and became a faith healer operating in Covent Garden.

- By Elizabeth Killigrew (1622–1680)

- Charlotte Jemima Henrietta Maria Boyle (FitzCharles) (1650–1684), Countess of Yarmouth

- By Catherine Pegge, Lady Green

- Charles Fitzcharles (1657–1680), known as "Don Carlos," created Earl of Plymouth (1675)

- Catherine Fitzcharles (born 1658, died young)

- By Barbara Palmer (1640–1709) (née Villiers), Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland

- Anne Palmer (Fitzroy) (1661–1722)

- Charles Fitzroy (1662–1730) created Duke of Southampton (1675), became 2nd Duke of Cleveland (1709)

- Henry Fitzroy (1663–1690), created Earl of Euston (1672), Duke of Grafton (1709), also seventh Great-Grandfather of Lady Diana Spencer, mother of Prince William of Wales

- Charlotte Fitzroy (1664–1718), Countess of Lichfield. She married Benedict Leonard Calvert, fourth Baron Baltimore.

- George Fitzroy (1665–1716), created Earl of Northumberland (1674), Duke of Northumberland (1683)

- Barbara (Benedicta) Fitzroy (1672–1737) She was acknowledged as Charles's daughter, but was probably the child of John Churchill, later Duke of Marlborough

- By Eleanor "Nell" Gwyn (1650–1687)

- Charles Beauclerk (1670–1726), created Duke of St Albans

- James Beauclerk (1671–1681)

- By Louise Renée de Penancoet de Kéroualle (1648–1734), Duchess of Portsmouth (1673)

- Charles Lennox (1672–1723), created Duke of Richmond (1675) in England and Duke of Lennox (1675) in Scotland. Ancestor of Lady Diana Spencer, The Duchess of Cornwall, and Sarah, Duchess of York.

- By Mary 'Moll' Davis, courtesan and actress of repute

- Mary Tudor (1673–1726), married to Edward Radclyffe (1655–1705), the Second Earl of Derwentwater from 1687 to 1705. Upon Edward's death, she married Henry Graham (son and heir to Col. James Graham), and upon his death she wed James Rooke in 1707. Mary bore four children to Edward, which continued the house of Derwentwater.

- By Unknown mistress

- Elizabeth Fitzcharles (1670–1731), married Sir Edward Morgan (1670–1734), the son of Sir James Morgan, fourth Earl Baronet of Llantarnam and his wife Lady Ann Hopton. She bore her husband ten children. Some sources give her surname as Jarman, however, that remains inconclusive.[4]

- Other mistresses

- Cristabella Wyndham

- Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin

- Winifred Wells, one of the Queen's Maids of Honor

- Mrs. Jane Roberts, the daughter of a clergyman

- Mary Sackville (formerly Berkeley, née Bagot), the widowed Countess of Falmouth

- Elizabeth Fitzgerald, Countess of Kildare

- Frances Teresa Stewart, Duchess of Richmond and Lennox

Notes

- ↑ British Library, Bombay: History of a City. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ↑ Bryant, Mark, Private Lives. 2001. p.73.

- ↑ Bryant, Mark, Private Lives. 2001. p.73.

- ↑ Scroggins, William G. Genealogical and Heraldic History.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abbot, Jacob. History of King Charles the Second of England.

- Brewer, E. Cobham. Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Wordsworth Editions Ltd. 1999. ISBN 9781853263002

- Fraser, Antonia. King Charles II. Phoenix. 2002. ISBN 9780753814031

- Fraser, Antonia (Edited). The Lives of the Kings and Queens of England. Cassel. 2001. p. 234-238. ISBN 9780304357239

- Hilliam, David. Kings, Queens, Bones and Bastards: Who's Who in the English Monarchy from Egbert to Elizabeth II. Sutton. 2004. ISBN 9780750935531

- History of the Monarchy. Charles II. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

| Preceded by: Charles I (de jure) Commonwealth of England (de facto) |

King of England 1660 (1649)–1685 |

Succeeded by: James VII & II |

| King of Scots 1660 (1649)–1685 | ||

| King of Ireland 1660 (1649)–1685 | ||

| Preceded by: Charles I of England |

Prince of Wales |

Succeeded by: James Francis Edward Stuart |

| Preceded by: The Duke of York |

Lord High Admiral 1673 |

Succeeded by: Prince Rupert of the Rhine |

| Preceded by: The Earl of Nottingham (First Lord of the Admiralty) |

Lord High Admiral 1684–1685 |

Succeeded by: King James II |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.