| Chestnut | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sweet Chestnut Castanea sativa

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Castanea alnifolia - Bush Chinkapin |

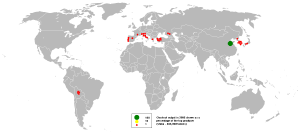

Chestnut is the common name for any of the deciduous trees and shrubs comprising the genus Castanea (Cas-tá-ne-a) in the beech family Fagaceae, native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere and characterized by alternate, simple, toothed leaves and fruit in the form of cup-like nuts enclosed in a prickly outer shell (burr). Eight or nine species have been identified as part of Castanea, including those chestnuts commonly called chinkapins, which typically are smaller, often more shrubby, than the other species of large trees. The name chestnut also refers to the edible nut of these trees and to the wood, which has commercial value.

There also are other plants in other genera and families that utilize the common name chestnut, including the horse chestnut (Aesculus in Sapindaceae family; also called "buckeye"), the grass-like Chinese water chestnut (Eleocharis dulcis in Cyperaceae family), and the water chestnut (Trapa natans in the Trapaceae family).

Chestnuts provide an important food resource for wildlife. (Paillet 2005) calls chestnuts "a nearly ideal food for mast-consuming wildlife [wildlife that eat fruits and nuts]" given they are not protected by a predator-resistant husk or shell or by chemicals. (See ecology.) Reflecting the harmony in nature, wildlife is also important to the chestnut's survival as a species, serving as seed-dispersal agents.

Humans also consume chestnuts, as reflected in the holiday song whose opening verse reads "Chestnuts roasting on an open fire." While chestnuts remain an important food crop in parts of Europe and Asia, their use in North America was greatly reduced in the early twentieth century when the chestnut blight killed vast numbers of the American Chestnut. Chestnuts also serve as an important ornamental tree and timber resource.

Description

The beech family, Fagaceae, to which chestnut belong, comprises about 900 species of both evergreen and deciduous trees and shrubs. Members of this family are characterized by alternate simple leaves with pinnate venation, unisexual flowers in the form of catkins, and fruit in the form of cup-like (cupule) nuts. Fagaceous leaves are often lobed and both petioles and stipules are generally present. Fruits lack endosperm and lie in a scaly or spiny husk (outer shell) that may or may not enclose the entire nut, which may consist of one to seven seeds. The best-known group of this family is the oaks, genus Quercus, the fruit of which is a nut (usually containing one seed) called an acorn. The husk of the acorn in most oaks only forms a cup in which the nut sits.

The chestnuts, genus Castanea, are mostly species with large trees growing to 20-40 meters tall, but some species (the chinkapins) are smaller, often shrubby. The leaves are simple, ovate or lanceolate, 10-30 centimeters long and 4-10 centimeters broad, with sharply pointed, widely-spaced teeth, separated by shallow rounded sinuses.

The flowers are catkins, produced in mid summer; they have a heavy, unpleasant odor.

The chestnut fruit is a spiny cupule 5-11 centimeters in diameter, containing one to seven thin-shelled nuts (Rushforth 1999; Bean 1976; FOC; FNA). These are true nuts in a botanical sense, not just a culinary sense. That is, the chestnut is a hard, indehiscent (not opening to discharge seeds), simple, dry fruit, whereby the plant's ovary wall becomes very hard (stony or woody) at maturity, and where the seed remains unattached or unfused with the ovary wall. The seed itself is protected by a thin shell. The spiny covering that protects the nut while immature, called a burr, opens wide when the seed is ripe (Paillet 2005).

The name Castanea comes from the old Latin name for the Sweet Chestnut (Huxley 1992).

Ecology

Chestnut trees thrive on neutral and acidic soils, such as soils derived from granite, sandstone, or schist, and do not grow well on alkaline soils such as chalk (Huxley 1992).

The nuts are an important food for such birds as jays and pigeons, and such mammals as squirrels, turkeys, bear, and deer. Several insects, notably the weevil Curculio elephas (chestnut weevil), also feed on the seeds (Huxley 1992).

Paillet (2005) notes that chestnut is unique among North American nut-producing trees in that there is little deterrence for seed predators, with the seed protected only by a thin shell and lacking tannins (as in acorns) or other chemicals to reduce palatability. The young chestnuts are protected by a burr that is formidable, but it opens wide when the seed is ripe (Paillet 2005).

Chestnuts, given their tendency to fall near the parent tree due to being heavy, rely on dispersal agents to provide effective dispersal of seeds. As with other interactions between seed predators and trees, the predators are rewarded for their role in planting nuts, while at least some nuts survive to germinate and grow (Paillet 2005).

The leaves are used as a food plant by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species.

Chestnuts grown for commercial nut production are grown in orchards with wide spacing between the trees to encourage low, broad crowns with maximum exposure to sunshine to increase nut production. On alkaline soils, chestnuts can be grown by grafting them onto oak rootstocks. Most wood production is done by coppice systems, cut on a 12-year-rotation to provide small timber which does not split as badly as large logs (Edlin 1970).

Chestnuts for planting require storage in moist sand and chilling over the winter before sowing; drying kills the seed and prevents germination.

Diseases

A fungal disease, chestnut blight Cryphonectria parasitica, affects chestnuts. The eastern Asian species have co-evolved with this disease and are moderately to very resistant to it, while the European and North American species, not having been exposed to it in the past, have little or no resistance (Huxley 1992).

Early in the twentieth century, chestnut blight was introduced to North America by the importation of Asian chestnut plants (AP 2007). In 1904, this fungus was detected in New York City and by 1950, 90 percent of the American chestnut trees, 3.5 billion trees, had died (AP 2007). What had been the most important tree throughout the east coast was reduced to insignificance. The American chinkapins are also very susceptible to chestnut blight. The European and west Asian Sweet Chestnut is susceptible, but less so than the American (Huxley 1992).

The resistant species, particularly Japanese Chestnut and Chinese Chestnut but also Seguin's Chestnut and Henry's Chestnut, have been used in breeding programs in the United States to create hybrids with the American Chestnut that are also disease resistant (AP 2007).

Uses

Nuts

The nuts are an important food crop in southern Europe, and southwestern and eastern Asia, and were an important food resource in eastern North America before the arrival of chestnut blight. Chestnuts also have been a traditional staple food: In southern Europe in the Middle Ages, whole forest-dwelling communities that had scarce access to wheat flour relied on chestnuts as their main source of carbohydrates.

Chestnuts are largely starch and water, with very little fat, and are a good source of dietary fiber and copper and a source of vitamins B1 and B6 (Bender and Bender 2005).

The nuts are peeled of their hard outer shells and bitter inner skin and then eaten candied, boiled, preserved, puréed, or roasted (Herbst 2001). Candied chestnuts are often sold under the French name marrons glacés or Turkish name kestane şekeri. Another important use of chestnuts is to be ground into flour, which can then be used to prepare bread, cakes, and pasta.

Another little known use is to eat chestnuts raw by just peeling them (almost unknown in North-America but customary at least in Northwest Europe). When chestnuts are fresh from the field/store, peeling is not easy. However, after leaving them out at room temperature for 24-48 hours, the consumer can easily peel away the outside shell using a simple small, pointed kitchen knife. The remaining process requires simply removing the thinner inside skin, washing the exposed fruit to remove any remaining contamination, and then eating. Chestnuts' taste may vary slightly from one to the next but is somewhat sweet and certainly unique. Chestnuts start to degrade if they are left out for more than five to seven days.

Chestnut-based recipes and preparations are making a comeback in Italian cuisine, as part of the trend toward rediscovery of traditional dishes.

Other products

Chestnut wood is similar to oak wood in being decorative and very durable. Due to disease, American chestnut wood has almost disappeared from the market. Although quantities of chestnut can still be obtained as reclaimed lumber, it is difficult to obtain large timber from the sweet chestnut due to the high degree of splitting and warping when it dries (Edlin 1970). The wood of the sweet chestnut is most commonly used in small items where durability is important, such as fencing and wooden outdoor cladding ('shingles') for buildings. In Italy, it is also used to make barrels used for aging balsamic vinegar.

The bark was also a useful source of natural tannins, used for tanning leather before the introduction of synthetic tannins (Edlin 1970).

Gallery

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Associated Press (AP). Breeders work for return of chestnut. Associated Press November 23, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- Bean, W. J. 1976. Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles, 8th ed., vol. 1. John Murray. ISBN 0719517907.

- Bender, D. A., and A. E. Bender. 2005. A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198609612.

- Edlin, H. L. 1970. Trees, Woods and Man. New Naturalist. ISBN 002132303.

- Flora of China. n.d. Castanea. Flora of China 4: 315. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- Flora of North America. n.d. Castanea. Flora of North America 3. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- Herbst, S. T. 2001. The New Food Lover's Companion: Comprehensive Definitions of Nearly 6,000 Food, Drink, and Culinary Terms. Barron's Cooking Guide. Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0764112589.

- Huxley, A. (ed.). 1992. The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0333770188.

- Paillet, F. L. 2005. Chestnut and wildlife. In K. C. Steiner and J. E. Carlson, eds., Proceedings of Conference on Restoration of American Chestnut to Forest Lands. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- Rushforth, K. 1999. Trees of Britain and Europe. Collins. ISBN 0002200139.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.