| Butterflies | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Blue Morpho, Family Nymphalidae | ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Families | ||||||||||

|

A butterfly is an insect of the Order Lepidoptera that belongs to either the superfamily Papilionoidea or the superfamily Hesperioidea (“the skippers”). Some authors would include also members of the superfamily Hedyloidea, the American butterfly moths. Although the skippers (superfamily Hesperioidea) are usually counted as butterflies, they are somewhat intermediate between the rest of the butterflies and the remaining Lepidoptera, the moths.

In reality, the separation of Lepidoptera into butterflies and moths is a common, not a taxonomic classification, and does not involve taxonomic rank.

Butterflies add important economic, ecological, and aesthetic values. As pollinators of flowers, butterflies aid in the cultivation of fruits and vegetables, and in the propagation of wild plant species. Ecologically, they serve as food for many animals—reptiles, fish, amphibians, birds, mammals, other insects, and spiders. Because of their sensitivity to environmental changes, they can serve as warning signs of deleterious conditions. Aesthetically, human fascination with butterflies has led to their being featured in paintings, poetry, and books, and as symbols used for jewelry, wallpaper, and so forth. Butterfly watching is a popular hobby. The life cycle of butterflies also has been depicted as an apt metaphor for eternal life, as the "earth-bound" caterpillar transforms into the ethereal butterfly.

People who study or collect butterflies (or the closely related moths) are called lepidopterists. The study of butterflies is known as butterflying. An older term for a lepidopterist is aurelian.

Some butterflies are now considered endangered species, and the Xerces blue butterfly is the first known butterfly to become extinct in North America.

Butterfly scales

Butterflies belong to Lepidoptera or scaly-winged insects (lepidos = scales and pteron = wings in Greek). Butterflies have fine scales on their wings that look like a fine powder. These scales are colored and result in giving striking colors and patterns to many butterflies, while providing cryptic colors and camouflage patterns to others. When touched by humans, the wings tend to lose some scales. If too many scales are lost, the butterfly's ability to fly will be impaired. The scales on the butterfly wings have many properties, mostly optical, that interest scientists. The patterns they make are also seen as the best animal system for understanding the developmental and genetic processes that produce morphological variation in nature.

Butterflies have been used as model organisms for a variety of fields of study, spanning ecology, evolutionary biology, and conservation biology (Boggs et al. 2003). Much of the theory on aposematism and mimicry arose from nineteenth-century studies by lepidopterists studying butterflies in the New World and the Orient. Considerable research by H. F. Nijhout and others have been done on developmental biology that have provided insights into the development of color patterns in butterfly wings.

Classification

Presently, butterflies are classified in two superfamilies, Hesperioidea, consisting of the 'skippers,' and Papilionoidea, or 'true butterflies.' Skippers differ in several important ways from the remaining butterflies. Skippers have the antennae clubs hooked backward, have stocky bodies, and possess stronger wing muscles and better eyes. However, Hesperioidea and Papilionoidea are considered sister taxa, so the butterflies collectively are thought to constitute a true clade. Some modern taxonomists place them all in superfamily Papilionoidea, distinguishing the skippers from the other butterflies at the series level only. In this system, Papilionoidea consists of the series Hesperiiformes (with one family only, the skipper family Hesperiidae) and the series Papilioniformes (with five families). When skippers are classified in the superfamily Hesperioidea, it also includes the one family, the Hesperiidae.

Butterfly families

The five families of true butterflies usually recognized in the Papilionoidea are:

- Family Papilionidae, the Swallowtails and Birdwings

- Family Pieridae, the Whites and Yellows

- Family Lycaenidae, the Blues and Coppers, also called the Gossamer-Winged Butterflies

- Family Riodinidae, the Metalmark butterflies

- Family Nymphalidae, the Brush-footed butterflies

Some common/well-known butterfly species

There are between 15,000 and 20,000 species of butterflies worldwide. Some well-known species from around the world include:

- Swallowtails and Birdwings, Family Papilionidae

- Swallowtail, Papilio machaon

- Spicebush Swallowtail, Papilio troilus

- Lime Butterfly, Papilio demoleus

- Ornithoptera genus (Birdwings; the largest butterflies)

- Whites or Yellows, Family Pieridae

- Small White, Pieris rapae

- Green-veined White, Pieris napi

- Common Jezebel, Delias eucharis

- Blues and Coppers or Gossamer-Winged Butterflies, Family Lycaenidae

- Xerces Blue, Glaucopsyche xerces

- Karner Blue, Lycaeides melissa samuelis (endangered)

- Red Pierrot, Talicada nyseus

- Metalmark butterflies, Family Riodinidae

- Lange's Metalmark Butterfly

- Plum Judy, Abisara echerius

- Brush-footed butterflies, Family Nymphalidae

- Painted Lady, or Cosmopolite, Vanessa cardui

- Monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus

- Morpho genus

- Speckled Wood, Pararge aegeria

- Skippers, Family Hesperiidae

- Silver-spotted skipper, Hesperia comma

- Aaron's Skipper, Poanes aaroni

- Chequered Skipper, Carterocephalus palaemon

- Small Skipper, Thymelicus sylvestris

Difference between butterflies and moths

Butterflies and moths are often confused with each other. This is understandable, given that separation of Lepidoptera into butterflies and moths is a common classification, not one that is recognized by taxonomists. The "moths" are an artificial group, defined only as everything in the order that is not a butterfly. Butterflies, on the other hand, are a natural group, in that they are all considered to have descended from a single common ancestor, but they do not have a formal taxonomic rank.

Although there are many ways of distinguishing a butterfly from a moth, there are exceptions to every rule. Among some of the means of distinguishing them are:

- Antennae. Most butterflies have thin, slender, filamentous antennae, which are club-shaped at the end, while moths often have comb-like or feathery antennae, or filamentous and unclubbed. This distinction is the basis for the non-standard taxonomic divisions in the Lepidoptera—the Rhopalocera ("clubbed horn," the butterflies) and the Heterocera ("varied horn," the moths).

- Wing coupling mechanisms. Many moths have a frenulum, which is a filament arising from the hindwing and coupling with barbs on the forewing. The frenulum can be observed only when a specimen is in hand. Butterflies lack these structures.

- Pupae. Most moth caterpillars spin a cocoon made of silk within which they metamorphose into the pupal stage. Most butterflies on the other hand form an exposed pupa, which is also termed as a chrysalis.

- Coloration of the wings. Most butterflies have bright colors on their wings. Nocturnal moths on the other hand are usually plain brown, gray, white, or black and often with obscuring patterns of zigzags or swirls, which help camouflage them as they rest during the day. However many day-flying moths are brightly colored, particularly if they are toxic. A few butterflies are also plain-colored, like the Cabbage White butterfly.

- Structure of the body. Moths tend to have a stout and hairy or furry-looking bodies, while butterflies have slender and smoother abdomens. Moths have larger scales on their wings that make them look more dense and fluffy. Butterflies, on the other hand, possess fine scales. This difference is possibly due to the need for moths to conserve heat during the cooler nights, whereas butterflies are able to absorb solar radiation.

- Behavioral differences. Most moths are nocturnal or crepuscular, while most butterflies are diurnal. Moths usually rest with their wings spread out to their sides. Butterflies frequently fold their wings above their backs when they are perched, although they will occasionally "bask" with their wings spread for short periods.

However, since there are many exceptions to each of these characteristics, it is perhaps better to think of butterflies as a group of day-flying moths.

Taxonomic issues

A major study (Wahlberg et al. 2005), combining morphological and molecular data, concluded that Hesperiidae, Papilionidae, Pieridae, Lycaenidae, and Riodinidae could all be strongly supported as monophyletic clades, but the status of Nymphalidae is equivocal. Lycaenidae and Riodinidae were confirmed as sister taxa, and Papilionidae as the outgroup to the rest of the true butterflies, but the location of Pieridae within the pattern of descent was unclear, with different lines of evidence suggesting different conclusions. The data suggested that the moths of Hedyloidea are indeed more closely related to the butterflies than to other moths.

Some older classifications recognize additional families, for example Danaidae, Heliconiidae, Libytheidae, and Satyridae, but modern classifications treat these as subfamilies within the Nymphalidae.

The four stages in the lifecycle of a butterfly

Unlike many insects, butterflies do not experience a nymph period (an immature insect, whose form is already that of an adult), but instead go through a pupal stage, which lies between the larva and the adult stage (the imago).

- Egg

- Larva, known as a caterpillar

- Pupa (chrysalis)

- Adult butterfly (imago)

Egg

Butterfly eggs consist of a hard-ridged outer layer of shell, called the chorion. This is lined with a thin coating of wax, which prevents the egg from drying out before the larva has had time to fully develop. Each egg contains a number of tiny funnel-shaped openings at one end, called micropyles; the purpose of these holes is to allow sperm to enter and fertilize the egg. Butterfly and moth eggs vary greatly in size between species, but they are all either spherical or ovate.

Butterfly eggs are fixed to a leaf with a special glue that hardens rapidly. As it hardens, it contracts deforming the shape of the egg. This glue is easily seen surrounding the base of every egg, forming a meniscus. The same glue is produced by a pupa to secure the setae of the cremaster. This glue is so hard that the silk pad, to which the setae are glued, cannot be separated.

Caterpillars

Larvae, or caterpillars, are multi-legged eating machines. They consume plant leaves and spend practically all of their time in search of food.

Caterpillars mature through a series of stages, called instars. Near the end of each instar, the larva undergoes a process called apolysis, in which the cuticle, the tough covering that is a mixture of chitin and specialized proteins, is released from the epidermis and the epidermis begins to form a new cuticle beneath. At the end of each instar, the larva molts the old cuticle, and the new cuticle rapidly hardens and pigments. Development of butterfly wing patterns begins by the last larval instar.

Wing development in larval stage

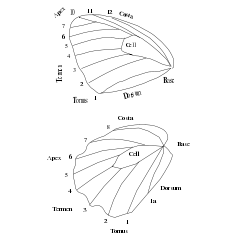

Butterflies belong to the specialized and prolific lineage of holometabolous insects, which means that wings or wing pads are not visible on the outside of the larva, but when larvae are dissected, tiny developing "wing disks" can be found on the second and third thoracic segments, in place of the spiracles that are apparent on abdominal segments.

Wing disks develop in association with a trachea that runs along the base of the wing, and are surrounded by a thin "peripodial membrane," which is linked to the outer epidermis of the larva by a tiny duct.

Wing disks are very small until the last larval instar, when they increase dramatically in size, are invaded by branching tracheae from the wing base that precede the formation of the wing veins, and begin to express molecular markers in patterns associated with several landmarks of the wing.

Near pupation, the wings are forced outside the epidermis under pressure from the hemolymph (the fluid in the open circulatory system), and although they are initially quite flexible and fragile, by the time the pupa breaks free of the larval cuticle they have adhered tightly to the outer cuticle of the pupa (in obtect pupae). Within hours, the wings form a cuticle so hard and well-joined to the body that pupae can be picked up and handled without damage to the wings.

Pupa

When the larva exceeds a minimum weight at a particular time of day, it will stop feeding and begin "wandering" in a quest for a suitable pupation site, usually the underside of a leaf. The larva transforms into a pupa (chrysalis), which then transforms into a butterfly by metamorphosis. To transform from the miniature wings visible on the outside of the pupa into large structures usable for flight, the pupal wings undergo rapid mitosis and absorb a great deal of nutrients. If one wing is surgically removed early on, the other three will grow to a larger size. In the pupa, the wing forms a structure that becomes compressed from top to bottom and pleated from proximal to distal ends as it grows, so that it can rapidly be unfolded to its full adult size. Several boundaries seen in the adult color pattern are marked by changes in the expression of particular transcription factors in the early pupa.

Adult Butterfly or Imago

The adult, sexually mature, stage of the insect is known as the imago. As Lepidoptera, butterflies have four wings that are covered with tiny scales, but, unlike most moths, the fore- and hindwings are not hooked together, permitting a more graceful flight. A butterfly has six legs; the larva also has six true legs and a number of prolegs. After it emerges from its pupal stage, it cannot fly for some time, because its wings have not yet unfolded. A newly-emerged butterfly needs to spend some time 'inflating' its wings with blood and letting them dry, during which time it is extremely vulnerable to predators.

Habits

Butterflies live primarily on nectar from flowers. Some also derive nourishment from pollen, tree sap, rotting fruit, dung, and dissolved minerals in wet sand or dirt. Butterflies play an important ecological role as pollinators.

As adults, butterflies are able to consume liquids only by means of their proboscis. They regularly feed on nectar and sip water from damp patches. This they do for water, for energy from sugars in nectar, and for sodium and other minerals that are vital for their reproduction.

Several species of butterflies need more sodium than provided by the nectar they drink from flowers. As such, they are attracted to the sodium in salt (which the males often give to the females to ensure fertility). As human sweat contains significant quantities of salt, they sometimes land on people, to the delight of the young at heart everywhere.

Besides damp patches, some butterflies also visit dung, rotting fruit, or carcasses to obtain the essential minerals that they need.

Butterflies sense the air for scents, wind, and nectar using their antennae. The antennae come in various shapes and colors. The hesperids have a pointed angle or hook to the antennae.

Some butterflies, such as the Monarch butterfly, are migratory. Indeed, the migration time of the Monarch butterfly far exceeds the lifetime of an individual Monarch.

Etymology

The Old English word for butterfly was buttorfleoge apparently because butterflies were thought to steal milk. A similar word occurs in Dutch originating from the same belief. This is considered to have led to the development of its present name form: butterfly.

An alternative folk etymology, current in Great Britain, is that it originated as a contraction of term butter-coloured fly referring to the Brimstone Butterfly Gonepteryx rhamni, often the first butterfly of spring. Earlier, it was mistakenly considered that the word butterfly came from a metathesis of "flutterby."

Additional photos

Family Papilionidae- The Swallowtails

Family Pieridae - The Whites and Yellows

Family Riodinidae - The Metalmarks, Punches and Judies

Family Nymphalidae - The Brush-footed Butterflies

Family Lycaenidae - The Blues

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bingham, C. T. 1905. Fauna of British India. Butterflies. Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis Ltd.

- Boggs, C., W. Watt, and P. Ehrlich. 2003. Butterflies: Evolution and Ecology Taking Flight. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226063186

- Heppner, J. B. 1998. Classification of Lepidoptera. Holarctic Lepidoptera, Suppl. 1.

- Pyle, R. M. 1992. Handbook for Butterfly Watchers. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Originally published 1984. ISBN 0395616298

- Wahlberg, N., M. F. Braby, A. V. Z. Brower, R. de Jong, M.-M. Lee, S. Nylin, N. E. Pierce, F. A. H. Sperling, R. Vila, A. D. Warren & E. Zakharov. 2005. Synergistic effects of combining morphological and molecular data in resolving the phylogeny of butterflies and skippers. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B (Biological Sciences) 272: 1577-1586.

Field guides to butterflies

- Butterflies of North America, Jim P. Brock and Kenn Kaufman. 2006. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0618768262

- Butterflies through Binoculars: The East, Jeffrey Glassberg. 1999. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195106687

- Butterflies through Binoculars: The West, Jeffrey Glassberg. 2001. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195106695

- A Field Guide to Eastern Butterflies, Paul Opler. 1994. Revised edition, 1998. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395904536

- A Field Guide to Western Butterflies, Paul Opler. 1999. ISBN 0395791510

- Peterson First Guide to Butterflies and Moths, Paul Opler. 1994. Second revised edition, 1998. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395906652

- Las Mariposas de Machu Picchu by Gerardo Lamas (2003)

- The Millennium Atlas of Butterflies in Britain and Ireland by Jim Asher (ed.), et al.

- Pocket Guide to the Butterflies of Great Britain and Ireland by Richard Lewington

- Butterflies of Britain and Europe (Collins Wildlife Trust Guides) by Michael Chinery

- Butterflies of Europe by Tom Tolman and Richard Lewington (2001)

- Butterflies of Europe New Field Guide and Key by Tristan Lafranchis (2004)

- Butterflies of Sikkim Himalaya and their Natural History by Meena Haribal (1994)

- Butterflies of Peninsular India by Krushnamegh Kunte (Universities Press, 2005)

- Butterflies of the Indian Region by Col. M. A. Wynter-Blyth (Bombay Natural History Society, Mumbai, India, 1957)

- A Guide to Common Butterflies of Singapore by Steven Neo Say Hian (Singapore Science Centre)

- Butterflies of West Malaysia and Singapore by W. A. Fleming (Longman Malaysia)

- The Butterflies of the Malay Peninsula by A. S. Corbet and H. M. Pendlebury (The Malayan Nature Society)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.