Concupiscence

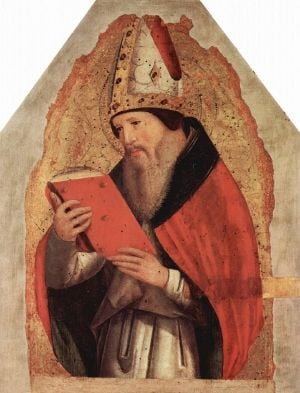

Concupiscence usually refers to sinful physical desire, especially sexual longing or lust. The term is derived from the Latin word concupiscentia, meaning "a desire for worldly things." In its widest sense, concupiscence is any yearning of the soul; in its specific sense, it means a desire of the lower appetite contrary to reason. The term has become especially important in discussions on the Christian concept of original sin, especially as developed by Augustine of Hippo.

Jewish tradition tends to consider the tendency to evil, known as the yetzer harah, as part of God's original creation, which Adam and Eve had to master by obeying God's commandment. Christian theology on the subject evolved out of the Pelagian controversy in the late fourth century C.E., when Saint Augustine propounded the doctrine of original sin in opposition to the belief in the possibility of moral perfection in earthly life. Catholic theology, following Augustine, teaches that Adam and Eve were once free from concupiscence. Since the Human Fall, however, concupiscence has degraded human freedom, so that no one is able to overcome the temptation to sin completely. Orthodox theology is somewhat less pessimistic, holding that humans can become substantially divinized through a combination of God's grace and humanity's prayerful effort. Protestant theology, though diverse, tends to see concupiscence as inherently sinful, rather than as a powerful tendency to sin.

Although few modern Bibles still use the word, it can be found in three passages of the King James Bible: Romans 7:8, Colossians 3:5, and I Thessalonians 4:5. More recent translations use terms such as "sin," "lust," or "evil desires" instead.

Jewish background

In Judaism, a parallel concept to concupiscence is the yetzer hara (Hebrew: ×׌ר ×רעâ for "evil inclination"), referring to the tendency to do evil by violating the will of God. Unlike in Christian theology, however, the yetzer hara is not the product of original sin, but a natural tendency to misuse things the physical body needs to survive.

Thus, through the yetzer hara, the need for food becomes gluttony, the natural urge to procreate leads to unethical sexual activity, and so on. In Judaism, this tendency toward evil is a natural part of God's creation, and God gives his commandments in order to guide and help mankind to master the yetzer hara.

Christian view

The Catholic teaching on concupiscence developed in the context of the so-called Pelagian controversy of the late fourth century C.E. The British monk Pelagius held that Christ had set a moral and spiritual example which other Christians could follow through ethical discipline and, thus, perfect their characters, in accordance with Jesus' command in Matthew 5:48: "Be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect."

Augustine of Hippo countered this optimistic view with the doctrine of original sin, in which he taught that, through their sin, Adam and Eve had passed on an innate tendency to sinâconcupiscenceâwhich could never be overcome by human effort, requiring God's intervening grace for salvation. Moreover, complete redemption from sin and the elimination of concupiscence will not occur for people living on earth until the Second Coming. In opposition to Pelagius' perfectionist ideal, he appealed to such scriptures as Saint Paul's tortured declaration:

I see another law at work in the members of my body, waging war against the law of my mind and making me a prisoner of the law of sin at work within my members. What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death? Thanks be to Godâthrough Jesus Christ our Lord (Romans 7:23-25).

The Catholic Church eventually declared Pelagianism to be heresy and adopted the Augustinian view. The Eastern Orthodox Church likewise rejected Pelagius, but went slightly less far than the Catholics, holding that while all humans indeed inherit a sinful nature from Adam and Eve, they are nevertheless capable of theosis (becoming divinized) through a combination of God's grace and human's prayerful effort.

Catholic teaching on concupiscence

In contrast to the Jewish view that the yetzer harah was endowed by God to Adam and Eve (who had to overcome it by obeying God's commandments), the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) teaches that Adam and Eve were originally constituted in a state of holiness free from concupiscence (CCC 337). By sinning, however, Adam lost this original state, not only for himself but for all human beings (CCC 416). Nevertheless, human nature has not been totally corrupted; rather, it has been weakened and wounded, subject to ignorance, suffering, death, and a powerful inclination to sin. This inclination toward sin and evil is called "concupiscence" (CCC 405, 418).

Baptism (preceded by repentance) erases original sin and turns a person back toward God. Concupiscence persists, however, and the original sin is passed on to one's children through the sexual act. Sex, while not evil in itself, is to be avoided except for purposes of procreation. Even after baptism, the struggle against concupiscence continues (CCC 2520) until Christ comes again to redeem humankind completely.

In its strict and specific sense, concupiscence is "a desire of the lower appetite contrary to reason." Due to original sin, the lower appetite in itself is unrestrained and seeks to pursue sensual gratification without regard to demands of reason and conscience. Hence, desires contrary to reason arise and dispose the bodily organs to tempt a person to sin. The rational will is able to resist such desires, but it is not capable of eliminating the effects they produce in the body. Thus, freedom of will in fallen humans is to some extent diminished. If a person resists the pull of concupiscence, a struggle ensues and the sensual appetite rebelliously demands gratification, while reason, clinging to its own spiritual interests, attempts to assert its control. Thus Paul wrote in Galatians 5:17: "The flesh sets its desire against the spirit, and the spirit against the flesh; for these are in opposition to one another, so that you may not do the things that you please."

Concupiscence, however, should not be confused with sin. The latter is the deliberate transgression of the law of God, and thus an act of will. Temptations to sin, on the other hand, naturally arise from concupiscence. The first parents, Adam and Eve, were originally free from concupiscence and were supposed to transmit this freedom to their posterity, provided they observed the commandment of God. This original freedom was not a result of Adam and Eve's own efforts but was a special gift of God. By the sin of Adam, freedom from concupiscence was forfeited. Through the Human Fall, the lower appetite began to lust against the spirit. Evil habits, brought on by personal sins, wrought disorder in the body, obscured the mind, and weakened the power of the will, although without destroying its freedom. Hence that lamentable condition of which St. Paul complained of in Romans 7:21-25.

Christ by his death redeemed humankind from sin and its bondage. In baptism the guilt of original sin is wiped out and the soul is cleansed and justified by the infusion of sanctifying grace. But freedom from concupiscence is not yet restored to humanity, any more than immortality. Abundant grace, however, is given him, by which he may obtain a degree of victory over the rebellious sense and deserve life everlasting.

Protestant views

The Reformers of the sixteenth century, especially Martin Luther, proposed new views respecting concupiscence, adopting the following propositions:

- Original righteousness was an integral part of human nature, rather than a special gift granted particularly to Adam and Eve.

- Concupiscence is of itself sinful, constituting the sinful corruption of human nature caused by Adam's transgression and inherited by all his descendants. It is thus the very essence of original sin.

- Baptism, since it does not extinguish concupiscence, does not do away with the guilt of original sin, although it does signal that God will not hold the repentant believer liable for it.

It should be kept in mind that the Protestant tradition has evolved into a very diverse one, with many differing positions on the subject. Many Protestant denominations, in fact, did not develop formal theological statements on the question of concupiscence as such.

See also

- Original sin

- Sin

- Lust

- Yetzer harah

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Augustine, and Philip Schaff. St. Augustine: Anti-Pelagian Writings. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1971. OCLC 25069666.

- John Paul II, and Michael Waldstein. Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body. Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 2006. ISBN 9780819874214.

- Kelly, David F. Sexuality and Concupiscence in Augustine. Dallas, TX: Annual of the Society of Christian Ethics, 1980. OCLC 30350007.

- Peters, Ted. Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1994. ISBN 9780802801135.

This article incorporates text from the Catholic Encyclopedia, a work now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved March 17, 2017.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.