| Saint Augustine of Hippo | |

|---|---|

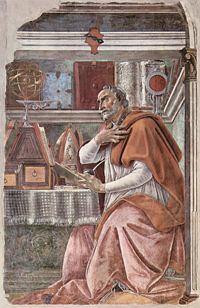

Augustine as depicted by Sandro Botticelli, c. 1480 | |

| Bishop and Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | November 13, 354 in Tagaste, Algeria |

| Died | August 28, 430 in Hippo Regius |

| Venerated in | most Christian groups |

| Feast | August 28 (W), June 15 (E) |

| Attributes | child; dove; pen; shell, pierced heart |

| Patronage | brewers; printers; sore eyes; theologians |

Augustine of Hippo or Saint Augustine (November 13, 354 – August 28, 430), bishop of Hippo, was one of the most important figures in the development of Christianity. His writings such as The Confessions and The City of God display his depth of faith and the theological skill of a trained rhetorician. His explanation of the doctrines of God, free will, evil, original sin, grace, illumination, and predestination have become standard for the majority of Christians. His Confessions is often called the first Western autobiography. His City of God defended Christianity from pagan accusations blaming it for the fall of the Roman Empire.

Born in what is present-day Algeria as the eldest son of Saint Monica, Augustine as a young man pursued a secular career as a teacher of rhetoric and philosophy while living a dissolute lifestyle. For nine years he was a follower of Manichaeism. In Milan he studied Neoplatonism and his conversion to Christianity took place in 386. As a theologian, he was called to write against the many heresies of the period—Manichaeanism, Donatism, and Pelagianism, and in so doing he defined the shape of orthodox doctrine.

In Roman Catholicism and the Anglican Communion, he is a saint and preeminent Doctor of the Church, and the patron of the Augustinian religious order. Many Protestants, especially Calvinists, consider him to be one of the theological fathers of the Reformation teaching on divine grace. In the Eastern Orthodox Church he is a saint, although a minority are of the opinion that he is a heretic, primarily because of his position on the filioque clause regarding the procession of the Holy Spirit. Among the Orthodox he is called "Blessed Augustine" or "St. Augustine the Blessed," not so much for his theological teachings as for his writings on spirituality.

Augustine's theology has received criticism especially for his teachings on predestination, which appears to exclude the reprobate from salvation, and on the use of force, through which to bring back heretics such as the Donatists, although that criticism may be based on a misconstruction of the real intent of Augustine. Also, sometimes his theology is critiqued for being tainted with Platonism and/or Neoplatonism. Nevertheless, his reputation as the preeminent Christian theologian is universally recognized.

Life

Augustine was of Berber descent and was born in 354 in Tagaste (present-day Souk Ahras, Algeria), a provincial Roman city in North Africa. His revered mother, Monica, was a Berber and a devout Catholic, and his father, Patricius, a pagan. At the age of 11 he was sent to school at Madaurus, a small Numidian city about 19 miles south of Tagaste. At the age of 17 he went to Carthage to continue his education in rhetoric. Although raised as a Catholic, Augustine left the Church to follow the controversial Manichaean religion, much to the despair of his mother. As a youth, Augustine lived a hedonistic lifestyle for a time and, in Carthage, he developed a relationship with a young woman who would be his concubine for over 15 years. During this period he had a son, Adeodatus, with the young woman.

Augustine’s education and early career was in philosophy and rhetoric, the art of persuasion and public speaking. In 383 he moved to Rome, where he believed the best and brightest rhetoricians practiced. However, he was disappointed with the Roman schools, which he found apathetic. Manichaean friends introduced him to the prefect of the city of Rome, Symmachus, who had been asked to provide a professor of rhetoric for the imperial court at Milan. The young provincial won the job and headed north to take up his position in late 384. At age 30, Augustine had won the most visible academic chair in the Latin world, at a time when such posts gave ready access to political careers. However, he felt the tensions of life at an imperial court, lamenting one day as he rode in his carriage to deliver a grand speech before the emperor, that a drunken beggar he passed on the street had a less careworn existence than he did.

It was at Milan that Augustine's life changed. While still at Carthage, he had begun to move away from Manichaeism, in part because of a disappointing meeting with a key exponent of Manichaean theology. At Milan, this movement continued. His mother, Monica, pressured him to become a Catholic, but it was the bishop of Milan, Ambrose, who had most influence over Augustine. Ambrose was a master of rhetoric like Augustine himself, but older and more experienced. Prompted in part by Ambrose's sermons, and partly by his own studies, in which he steadfastly pursued a quest for ultimate truth, Augustine renounced Manichaeism. After a flirtation with skepticism, he then became an enthusiastic student of Neoplatonism, and for a time believed he was making real progress in his quest.

Augustine's mother had followed him to Milan, and he allowed her to arrange a society marriage, for which he abandoned his concubine. But he had to wait two years until his fiancée came of age. So, he promptly took up in the meantime with another woman. It was during this period that he uttered his famous prayer, "Grant me chastity and continency, but not yet" (da mihi castitatem et continentiam, sed noli modo).[1]

In the summer of 386, after having read an account of the life of Saint Anthony of the Desert which greatly inspired him, Augustine underwent a profound personal crisis and decided to convert to Christianity, abandon his career in rhetoric, quit his teaching position in Milan, give up any ideas of marriage, and devote himself entirely to serving God and the practices of priesthood, which included celibacy. Key to this conversion was the voice of an unseen child he heard while in his garden in Milan telling him in a sing-song voice to "tolle lege" ("take up and read") the Bible, at which point he opened the Bible at random and fell upon Romans 13:13, which reads: "Let us walk honestly, as in the day; not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying" (KJV). He would detail his spiritual journey in his famous Confessions, which became a classic of both Christian theology and world literature. Ambrose baptized Augustine, along with his son, Adeodatus, on Easter Vigil in 387 in Milan, and soon thereafter in 388 he returned to Africa. On his way back to Africa his mother died, as did his son soon after, leaving him alone in the world without family.

Upon his return to North Africa Augustine created a monastic foundation at Tagaste for himself and a group of friends. In 391 he was ordained a priest in Hippo Regius, (now Annaba, in Algeria). He became a famous preacher (more than 350 preserved sermons are believed to be authentic), and was noted for combating the Manichaean heresy, to which he had formerly adhered. In 396 he was made coadjutor bishop of Hippo (assistant with the right of succession on the death of the current bishop), and remained as bishop in Hippo until his death in 430. During the period as bishop of Hippo, he combated the Donatist and Pelagian heresies. Although he left his monastery, he continued to lead a monastic life in the episcopal residence. He left a Rule (Latin, Regula) for his monastery that has led him to be designated the "patron saint of regular clergy," that is, clergy who live by a monastic rule.

Augustine died on August 28, 430, at the age of 75, during the siege of Hippo by the Vandals. He is said to have encouraged its citizens to resist the attacks, primarily on the grounds that the Vandals adhered to the Arian heresy. It is also said that he died just as the [Vandals were tearing down the city walls of Hippo.

Works

Augustine was one of the most prolific Latin authors, and the list of his works consists of more than a hundred separate titles.[2] They include apologetic works against the heresies of the Donatists, Manichaeans, and Pelagians as well as of the Arians, texts on Christian doctrine, notably "On Christian Doctrine" (De doctrina Christiana), exegetical works such as commentaries on Genesis, the Psalms and Paul's Epistle to the Romans, many sermons and letters, and the "Retractions" (Retractationes), a review of his earlier works which he wrote near the end of his life. Apart from those, Augustine is probably best known for his Confessions, which is a personal account of his earlier life, and for "The City of God" (De Civitate Dei), consisting of 22 books, which he wrote to restore the confidence of his fellow Christians, which was badly shaken by the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410.

Formulation of His Theology against Heresies

| Part of a series of articles on Christianity | ||||||

| ||||||

|

Foundations Bible Christian theology History and traditions

Topics in Christianity Important figures | ||||||

As the Christian Church was seriously faced with the three heresies of Manichaeism, Donatism, and Pelagianism chronologically around the life time of Augustine, he proved to be a central and influential theological leader that clarified and defended the Christian faith against these heresies. Augustine wrote many treatises and letters against these heresies, and this was how his theology was developed and formulated. Hence the polemical character of his theology. Nevertheless, his theology turned out to be creative and insightful, influencing later Christian theology.

Against Manichaeanism

Manichaeism was founded by Mani, a Persian, in the third century. As a mixture of Zoroastrianism, the old Babylonian religion of the Ophitic type, gnosticism, etc., it was a dualistic religion of the two separate, co-eternal principles of light (God) and darkness (Satan). It became widespread throughout the Roman Empire till the fifth century, even influencing Christians. Augustine himself was drawn to Manichaeism for nine years before his conversion for at least two reasons: firstly, because his question of why evil is so virulent in the world seemed to be plausibly addressed by its dualistic view of the world as a mixture of God and Satan; and secondly, because he felt exempted from any responsibility for his own sin due to the Manichaean fatalism. But, as soon as he became a Christian, Augustine felt the need for protecting the Church from the Manichaean heresy.

Whereas Manichaeism believed that the power of God is limited in front of Satan, Augustine affirmed that God is all-powerful, supreme, infinite, and immutable, and that Satan did not exist from eternity. Whereas Manichaeism asserted that the world is a mixture of good and evil, Augustine held that all creatures are good. For him, as for Neoplatonism, all being is good. Against the Manichaean view of evil as substantial, Augustine presented his view of evil as non-substantial. For him, as for Neoplatonism, if all being is good, then evil is non-being (non esse) or non-substance (non substantia). To be more precise, evil is the privation of good (privatio boni). It is the privation, diminution, or falling away (defectus) of a good being from what it originally is in terms of measure, form, and order, but it is still non-substantial as mere privation or diminution: "Evil is that which falls away from essence and tends to non-existence."[3] Against the pessimistic determinism of Manichaeism that deemed evil as necessary, Augustine presented an indeterminism that regarded evil only as possible. Evil is only possible because all being, which is originally created to be good, is still finite, changeable, and corruptible as it only participates in God who is infinite, unchangeable, and incorruptible as the supreme good. Whereas Manichaeism blamed God and Satan for evil as its authors and did not blame humans for evil, Augustine attributed the possibility of evil to the "free will" (liberum arbitrium) of rational creatures such as angels and humans. According to Augustine, free will is originally created to be good, but the privation or diminution of the moral rectitude which free will is originally endowed with is possible, and when it happens as in the case of Adam's fall, it constitutes moral evil, which is sin. When it comes to the question of how this moral evil starts, however, Augustine seems to have had no real answer. For he admitted that there is no efficient cause of an evil will, while God is the efficient cause of a good will: "as to whence it [evil] is, nothing can be said."[4]

Augustine's refutation of Manichaeism, although it was quite Neoplatonic, issued in a distinctive definition of God, a non-substantive theme of evil, and a free-will defense, all of which became important elements of the Christian tradition.

Against Donatism

The Donatists were a heretical group of rigorist Christians. This heresy started in 311 C.E. when Caecilianus was consecrated as bishop of Carthage by Felix, who had been a traditor (traitor) during the Diocletianic persecution (303-305). Questioning the efficacy of that consecration, they set up Majorinus against Caecilianus in the same year, and in 315 Majorinus was succeeded by Donatus, after whom this heresy was named. The Donatists claimed to be the only faithful and pure Christians, and asserted that no one outside the Donatist Church is holy enough to be able to administer the sacraments, and that if you want to be admitted to the Donatist Church, you must be rebaptized. After being persecuted by Emperor Constantine, these schismatics became resentful, furious, and even violent. The unity of the Christian Church was severely threatened.

Augustine took pains to address this problem from around 396. His work "On Baptism, Against the Donatists" was definitive.[5] He distinguished between the gift of baptism itself and the efficacious use of it, by saying that the former exists everywhere, whether inside or outside of the Catholic Church, but that the latter exists only in the place where the unity of love is practiced, i.e., the Catholic Church. In other words, baptism can be conferred even by heretics and schismatics as long as they give it in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, because the real source of baptism is God and not any human being. But, it will be only after you come back to the Church that your baptism received outside of the Church becomes efficacious. You don't have to be rebaptized. The Catholic Church, of course, is far from perfect, containing bad Christians as well as good ones, but if they love one another, baptism conferred will be efficaciously and profitably used. In order to show the importance of the unity of love in the Church for the efficacy of baptism, Augustine referred to St. Cyprian's praise of Saint Peter who was so humble, patient, and loving as to be corrected even by St. Paul, his junior. In Augustine's ecclesiology, love is an essential element of the Church.

Augustine also showed much love and sympathy for the Donatist heretics, urging them to come back. Originally, therefore, he opposed the use of force for their coming back in favor of gentle discussion and instruction. Later, however, he felt some need for a practical way to cope with the violence of armed Donatist zealots, and referred to Luke 14:23 ("compel them to come in") to support the use of force,[6] which the Church subsequently adopted to justify the Inquisition unfortunately. Augustine is, therefore, often blamed for having started this notorious tradition. But, many believe that this negative assessment of Augustine is not completely accurate.[7][8] For he apparently understood the use of force to be only an act of love and not of hatred, like when God out of love forced Paul into correction and faith through physical blindness, or when we forcibly save people from a building about to collapse.[9]

Against Pelagianism

Pelagianism was named after Pelagius, a monk from Britain, who, as a contemporary of Augustine, stressed the moral ability of Christians to stay sinless if they will even without any supernatural assistance of grace from God. For Pelagius, divine grace merely consists in the fact that we are endowed with free will, law, and gospel. He also rejected original sin, saying that what we have in front of us is merely Adam's bad example, which we can overcome through our moral efforts. The Pelagian controversy started soon after Coelestius, a young capable lawyer, became the chief disciple of Pelagius and drew much public attention. Again, the unity of the Church was at stake theologically.

Grace

Augustine was convinced of the ineffableness of God's grace and the absolute dependence of humans on God. In 412 he was asked by the imperial official of Carthage to address the problem of the Palegian heresy. Augustine affirmed the reality of original sin, by saying that the entire human race partakes of Adam's sin both in terms of "guilt" and "corruption." Given corruption, our free will is injured and enslaved. So, God's grace is necessary in order to liberate free will from its injury and enslavement to sin. After the liberation of free will, however, God's grace is also necessary, so it may act through liberated free will. Augustine called these two distinguishable stages of divine grace "operating grace" (gratia operans) and "co-operating grace" (gratia cooperans), respectively.[10] "Operating grace" is prevenient in that it precedes human free will that is "small and weak." It is also gratuitous and unmerited in that it is unconditionally given only on the ground of God's infinite mercy and undeserved favor. By contrast, "co-operating grace" is given subsequently to work with liberated "great and robust" free will.

Marriage

The Pelagians apparently talked about the purity and holiness of marriage and sexual appetite, blaming Augustine's view of original sin for making marriage evil. In response, Augustine distinguished between marriage and concupiscence (lustful desire), saying that marriage is good, while concupiscence is evil, and that concupiscence is not the essence of marriage but an accident of it.[11] Marriage is good because it is a sacrament that shows a bond of love centering on God and also because it involves sexual union for procreation. The evil of concupiscence does not destroy the goodness of marriage, although it conditions the character of the offspring through the transmission of original sin which it allows for in sexual union. In this context, sexual union for the gratification of lust in marriage is discouraged as venial sin. Furthermore, virginity is preferred to marriage in spite of the goodness of marriage.

Original sin and its transmission

Augustine was not the first to talk about original sin. Before him, Church Fathers such as Tertullian, Cyprian, and Ambrose discussed about it. But Augustine took the subject more seriously. According to Augustine, original sin is the sin of disobedience committed by Adam when he fell, and it affects all his descendants because the whole essence of human nature was contained in him. This solidarity of all individual humans through the fallen essense of human nature, according to Eugène Portalié, reflects Augustine's Platonic realism.[12] Original sin thus explained contains both "guilt" and "corruption." (Note that Eastern Orthodoxy, by contrast, refers to original sin only in terms of "corruption," thus not taking original sin as seriously as Augustine.) Thus, we are all both guilty of Adam's sin and corrupted in our human nature. Augustine's further explanation of how original sin is transmitted from generation to generation is noteworthy. According to him, it is transmitted through sexual intercourse, although Adam's fall itself did not involve any sexual intercourse. After Adam's fall, however, sexual intercourse even in lawful marriage can never avoid concupiscence, which is a bad sexual desire. Concupiscence totally overwhelms parents engaged in sexual intercourse for procreation, depriving them of self-control and rational thought, although it is permissible for the purpose of procreation. This is how original sin is transmitted from parents to their child: "Wherefore the devil holds infants guilty who are born, not of the good by which marriage is good, but of the evil of concupiscence, which, indeed, marriage uses aright, but at which even marriage has occasion to feel shame."[13] Predestination

During and after the Pelagian controversy, Augustine developed a doctrine of predestination in accordance with his doctrine of unmerited "operating grace." God chooses the elect gratuitously, without any previous merit on their part, and even before the foundation of the world God predestines who the elect are. The number of the elect "is so certain that one can neither be added to them nor taken from them."[14]

One might wonder if Augustine's emphasis on grace and predestination was contradictory to his earlier emphasis on free will during the Manichaean controversy. In fact, the Pelagians themselves appealed to his earlier, anti-Manichaen work, "The Free Choice of the Will," written in 395. But, it should be noted that throughout his entire theological career Augustine himself never abandoned his doctrine of free will. So, there seems to have been no contradiction in the mind of Augustine. According to him, divine knowledge is the key to reconciling predestination and free will. For God predestines to save those who he foreknows will choose to be saved through their free wills:

…they themselves also exhort to chastity, charity, piety, and other things which they confess to be God's gifts, and cannot deny that they are also foreknown by Him, and therefore predestinated; nor do they say that their exhortations are hindered by the preaching of God's predestination, that is, by the preaching of God's foreknowledge of those future gifts of His.[15]

According to Augustine, therefore, it is always correct to say that all can be saved if they wish. This unique way of reconciling predestination and free will by Augustine, which was further developed by the Jesuit theologian Luis de Molina in the sixteenth century, was not recognized by Protestant Reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin nor by prominent historians of theology such as Adolf von Harnack and Friedrich Loofs. According to The Catholic Encyclopedia, Augustine never taught the absolute type of predestinarianism of Calvin and others, and its origin "must be traced back to the misunderstanding and misinterpretation of St. Augustine's views relating to eternal election and reprobation."[16]

Other Theological Developments

The Trinity

It took Augustine many years to finish writing his treatise On the Trinity (De Trinitate), spanning a period from 400-416, because he was sometimes in bad health and he was also busy in being involved with the Donatist controversy. But, the treatise was not polemical (except sporadically when arguing against Arianism), as there was no concerted attack upon the doctrine of the Trinity. His intention was to help strengthen the faith of his fellow Catholics in the mystery of the Trinity through the Bible (books 1-7) and also through his unique analogy of psychology (books 8-15). Apparently due to his lack of knowledge of Greek, Augustine did not read the trinitarian writings of Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers except translated excerpts from them, thus not even referring to the Nicene word of homoousios ("of the same substance"). But, his treatise turned out to be one of his most important accomplishments.

According to Augustine, although the Father sends the Son and the Holy Spirit, the Son and the Holy Spirit are not inferior to the Father. Of course, in order to argue for the unity of the three persons, the Greek Fathers had already talked about the "mutual indwelling" (perichoresis) of the three persons, and Augustine did not disagree. But, the theory of mutual indwelling apparently had the threeness of the Trinity as its presupposition. Augustine now went the other way around, by saying that the oneness of the divine nature is prior to the threeness of the Trinity because the divine nature is held in common by the three persons. According to Augustine, the three persons are so united and co-equal that they are just one person in a way: "since on account of their ineffable union these three are together one God, why not also one person; so that we could not say three persons, although we call each a person singly."[17] Hence his belief also that creation, redemption, and sanctification, i.e., the external operations of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, are indivisible (opera trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt). Needless to say, he held that the Holy Spirit proceeds for the Father and the Son.

Augustine's psychological analogy of the Trinity is very original. According to this, as human beings were created in the image of God, an image of the Trinity should be found in them and especially in the psychology of the human mind. He pointed to many vestiges of the Trinity in the human mind such as: 1) lover, loved, and their love; 2) being, knowing, and willing; 3) memory, understanding, and will; and 4) object seen, attention of mind, and external vision. From this started the Catholic doctrine of vestiges of the Trinity in creation (vestigia trinitatis in creatura).

Divine illumination

When the human mind or soul, which is finite and mutable, perceives sense objects, which are also finite and mutable, how certain is its perception of the objects? This is the problem of certitude in perception. Can our perception acquire eternal and immutable truths about the objects which are finite and mutable? Plato answered this in the affirmative through his theory of recollection of eternal ideas. Augustine, too, answered it in the affirmative, but his approach was different from Plato's because he as a Christian did not believe in Plato's notion of the pre-existence of the soul. Following Plotinus' crucial notion that the eternal ideas or forms subsist in the mind of God, therefore, Augustine suggested that if divine illumination comes upon us and the sense objects to be known by us, then the eternal ideas or forms which are subjoined to these objects will be seen by us, with the result that we acquire eternal and immutable truths about the objects: "the intellectual mind is so formed in its nature as to see those things [i.e., eternal ideas or forms], which by the disposition of the Creator are subjoined to things intelligible [i.e., sense objects to be known] in a natural order, by a sort of incorporeal light of a unique kind." And it is just like the physical eye can see things if there is corporeal light from the sun, i.e., "as the eye of the flesh sees things adjacent to itself in this bodily light."[18] Thus, when the eternal ideas or forms subjoined to the objects are illumined by God, they constitute our criteria of judging and evaluating the objects.

Later, the Franciscans interpreted this to mean that God's illumination directly infuses and impresses the eternal ideas or forms upon the human mind for its judgment and evaluation of the objects. But this interpretation seems to regard human beings merely as passive receivers of God's intellectual activity. Perhaps, our role should be more active, given Augustine's admission that the eternal ideas or forms are already existent in the human mind in some way: "unless something of our own [mind] were subjoined to them [i.e., eternal ideas or forms], we should not be able to employ them as our measures by which to judge of corporeal things."[19]

Creation of the world

Interpreting Genesis

Augustine took the view that the biblical text of Genesis should not be interpreted literally if it contradicts what we know from science and our God-given reason. In an important passage in his The Literal Meaning of Genesis, he wrote:

Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars and even their size and relative positions, about the predictable eclipses of the sun and moon, the cycles of the years and the seasons, about the kinds of animals, shrubs, stones, and so forth, and this knowledge he holds to as being certain from reason and experience. Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. The shame is not so much that an ignorant individual is derided, but that people outside the household of the faith think our sacred writers held such opinions, and, to the great loss of those for whose salvation we toil, the writers of our Scripture are criticized and rejected as unlearned men. If they find a Christian mistaken in a field which they themselves know well and hear him maintaining his foolish opinions about our books, how are they going to believe those books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven, when they think their pages are full of falsehoods on the facts which they themselves have learned from experience and the light of reason?[20]

Thus, Augustine took the view that everything in the universe was created simultaneously by God, and not in seven calendar days like a plain account of Genesis would require. He argues that the six-day structure of creation presented in the book of Genesis represents a logical framework rather than the passage of time in a physical way — it would bear a spiritual, rather than physical, meaning, which is no less literal. He also didn't envisage original sin as originating structural changes in the universe, and even suggests that the bodies of Adam and Eve were already created mortal before the Fall.

A more clear distinction between "metaphorical" and "literal" in literary texts arose with the rise of the Scientific Revolution, although its source could be found in earlier writings such as those of Herodotus (fifth century B.C.E.). It was even considered heretical to interpret the Bible literally at times.

Time and eternity

The eleventh book of Augustine's Confessions consists of an extended meditation on the nature of time. According to Augustine, God exists outside of time in the "eternal present," and time only exists within the created universe because only in space is time discernible through motion and change. His meditation on the nature of time is closely linked to his consideration of the human soul's ability of memory. While time is discernible through motion and change, eternity is not. So, eternity does not refer to an indefinite extension of time, but to motionlessness and changelessness.

This distinction of time and eternity means that "the world was made, not in time, but simultaneously with time."[21] In other words, the creation of the world is not in time. It brings forth two interesting points. First, where there is no created world, there is no time. This means that there was no time when there was no created world. Thus, the created world existed at all times (i.e., always). Second, God's act of creating the world did not take time; it had no temporal duration. God created all things at once. This is not acceptable to today's "old-earth creationism," but it may be closer to "young-earth creationism," although it is not exactly same as the latter that believes that all things were created in six 24-hour days, taking the text of the first chapter of Genesis literally.

Augustine's contrast between time and eternity has been subscribed to by many theologians. But sometimes scholars such as Etienne Gilson pointed out that this contrast may contain a difficulty: Given the two rather heterogeneous modes of being, i.e., the created realm of changing things and the divine realm of changelessness, how can we who belong to the created realm present God to ourselves? To put it conversely, how can God create, know, and administer the world? Augustine simply confessed that the relationship of God and the world is a "mystery."[22]

Creation ex nihilo

Augustine realized that God in Manichaeism is violable, corruptible, and changeable, as long as it believes that the world is a mixture of the substances of God and Satan. In order to defend the inviolability, incorruptibility, and unchangeability of the omnipotent God of Christianity, therefore, he asserted that God creates the world ex nihilo ("out of nothing"): "He is so omnipotent, that even out of nothing, that is out of what is absolutely non-existent, He is able to make good things."[23] Unlike the Manichaean view of the world as inevitably evil, Augustine understood created beings to be good, because they are only from God. Even hyle, formless matter, is good because it is created by God. But, it should be noted that while Augustine regarded God as the highest good, he believed that created beings are good only to lesser degrees. This difference is that while God as the highest good is incorruptible and unchangeable, created beings, which are good, are corruptible and changeable, thus still having the possibility of evil. Augustine, of course, learned the fundamental goodness of the world from the emanationist monism of Neoplatonism, but he distanced himself from Neoplatonism in his assertion that created beings are not of the same substance with God as they are not "of" (de) God, but merely "from" (ex) God.[24]

The two Cities

When Alaric and his Visigoths sacked the city of Rome in 410, some claimed that it happened because the traditional gods of Rome were angry with people who accepted the Christian religion to the neglect of worshipping them. In order to defend Christianity from this accusation and also to explain how the end of the world will come, Augustine wrote his monumental work The City of God (De Civitate Dei) from 413 to 430. According to Augustine, the Cain-type earthly City and the Abel-type City of God were respectively founded based on "love of self" to the point of a contempt of God, on the one hand, and "love of God" to the point of self-contempt, on the other.[25] The two Cities are intermingled in conflict and struggle with each other throughout history within God's providential plan. There are seven successive periods in history based on the seven days of creation: 1) Adam to Noah; 2) Noah to Abraham; 3) Abraham to David; 4) David to the Babylonian captivity; 5) the Babylonian captivity to Christ; 6) Christ to the end of the world; and 7) the Sabbath. The two Cities struggle with each other during the first six periods, but are to be separated through the Judgment at the end of the sixth period, i.e., the period of the Church. The earthly City will be permanently judged, while the City of God will be in heaven forever. This Augustinian view of history continued to be dominant until the eighteenth century.

It should be noted that Augustine as a Platonist meant that the City of God is in heaven and not here on the earth. So, even the Church on the earth is not the City of God itself but merely its earthly representative, "symbolic presentation," or "foreshadowing image."[26] But still, the Church and other, previous representatives of the City of God in history such as Israel are vehicles by which to pursue internal, spiritual transformation and eternal peace in the City of God, whereas secular states within the earthly City only establish external order and temporal peace even by force. States wage wars to gain peace, but this kind of peace is not eternal. For Augustine, state and religion are separate, although they can cooperate to guide the lives of humans in this world.

Just war

Augustine believed that, given Jesus Christ's call for his followers to be "peacemakers" (Matthew 5:9) using no violence (Matthew 5:38-42), war is a lamentable sin taking place in the earthly world, and that it can never establish eternal peace. He, however, also believed from a practical point of view that if it is necessary to defend the innocent against evil, violence may be used. This constituted his theory of "just war." He suggested at least two requirements for just war: proper cause and proper authority. The first requirement means that wars be waged only for the purpose of establishing peace, although that peace may be temporal here on the earth. The second requirement is that wars be waged by governing authorities, because they are established by God in the natural world for a providential reason. Thus,

- A great deal depends on the causes for which men undertake wars, and on the authority they have for doing so; for the natural order which seeks the peace of mankind, ordains that the monarch should have the power of undertaking war if he thinks it advisable, and that the soldiers should perform their military duties in behalf of the peace and safety of the community.[27]

Thus, other motives such as "love of violence, revengeful cruelty, fierce and implacable enmity, wild resistance, and the lust of power" should be avoided.[28] In this context, Augustine also mentioned about the just treatment of prisoners-of-war and conquered peoples, making it clear that mercy should be shown to them, particularly if they are no longer a threat to peace.

Over the centuries, more requirements for just war have been added, such as a reasonable chance of success and the principle of proportionality of harm between warring states. But, Augustine was perhaps the first major theologian to discuss about just war.

On the Jews

Although the Jews was not a major theme in Augustine's voluminous writings, his view of the status of the Jews was quite original and influential throughout the Middle Ages. So, it deserves our attention. Augustine, of course, followed the patristic tradition that preceded him, that in terms of the role of Israel as the chosen people the Jews were superseded by the Christians at the time of Jesus' death and resurrection. He, therefore, referred to the Christians as the new Israel. But, the question was: If the Christians are the new Israel, why is it that the Jews still continue to exist after their dispersion. Augustine's originality consisted in his assertion that the Jews continue to exist as witnesses to the truth of Christianity, by witnessing the Old Testament prophesies about Jesus' death and resurrection and their own dispersion, which were never forged by the Christians:

- But the Jews who slew Him, and would not believe in Him, because it behooved Him to die and rise again, were yet more miserably wasted by the Romans, and utterly rooted out from their kingdom, where aliens had already ruled over them, and were dispersed through the lands (so that indeed there is no place where they are not), and are thus by their own Scriptures a testimony to us that we have not forged the prophecies about Christ.[29]

Augustine used Psalm 59:11 ("But do not kill them, O Lord our shield, or my people will forget") to argue that the Jews are to be allowed not to face slaughter in the Christian world as witnesses for that purpose. He also referred to the Jews as Cains that are cursed but are to be converted to Christianity eventually.

Many people regard this position of Augustine as antisemitic, although scholars such as John Y.B. Hood and Paula Fredriksen believe that it was a Christian defense of the Jews, saying that it served to protect their lives from the brutality of Cristendom's coercive powers in the Middle Ages.[30]

Fusion of Platonism and Christianity

Augustine was the outstanding figure in philosophy between the time of Plato and Thomas Aquinas, a period of 1,600 years that even covered the lives of well-known thinkers such as Aristotle. Augustine introduced the fusion of Platonism and Christianity, made possible through his readings of Apuleius, Plotinus, and Porphyry. One thing that made it possible for him to fuse the Platonic tradition in philosophy with Christianity is the fact that the latter is not a philosophy but rather a set of historical beliefs. The basic idea of Christianity is that God made our world and then came to live in it through Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus lived in a particular part of the world at a particular time and lived a particular historical course. Being a Christian involves believing this, as well as living the way that God told us to do, through Jesus, also known as the logos or "the Word" especially in the Gospel of John. While the Parables of Jesus did provide us with a good deal of moral instruction, Jesus or the Word gave little discussion of philosophical questions.

In the Platonic tradition, ideas are more real than things. Plato developed a vision of two worlds: a world of unchanging ideas and a world of changing physical objects (i.e., the experience of the historical Jesus). It was not the case that there were two philosophies: a Platonic philosophy, and on the other hand the Christian philosophy — thus giving Augustine the problem of marrying the two. It is more accurate to say that Christianity was not a philosophical religion like Buddhism, and that Augustine believed that the Platonic philosophy embodied important truths about aspects of reality that the Bible did not concern itself with. He wanted Platonism to be absorbed into the worldwide Christian view.

Of course, Augustine realized it was important not to take on board any particular aspect of Platonism that might have as one of its logical consequences something that contradicts Christianity. For it was believed by Christians at that time that any idea in contradiction to the Christian beliefs as the self revelation of God was heresy. He knew that any new ideas were always dictated by prior Christian claim to the truth. He saw new philosophical ideas as playing a secondary role to the religious revelation. Nonetheless, Augustine was successful in his aim of getting Platonic ideas absorbed into the Church's view of the nature of reality. In his philosophical reasoning, he was greatly influenced by Stoicism, Platonism, and Neoplatonism, particularly by the work of Plotinus, author of the Enneads, probably through the mediation of Porphyry and Victorinus. His generally favorable view of Neoplatonic thought contributed to the "baptism" of Greek thought and its entrance into the Christian and subsequently the European intellectual tradition.

Augustine remains a central figure both within Christianity and in the history of Western thought, and is considered by modern historian Thomas Cahill to be "almost the last great classical man — very nearly the first medieval man."[31] Thomas Aquinas took much from Augustine's theology while creating his own unique synthesis of Greek and Christian thought after the widespread rediscovery of the work of Aristotle. Augustine's early and influential writing on the human will, a central topic in ethics, would become a focus for later philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Assessment

Augustine made many important, lasting contributions for Christian theology. He is perhaps "the most influential Christian thinker of all time outside of the New Testament."[32] The central role of Augustine in Western Christianity is perhaps comparable to that of Moses in Judaism. Like Moses led the Israelites towards the land of Canaan from their 400-year slavery in Egypt by encouraging them to stay away from idol-worshipping, Augustine led the Christians towards the City of God from their 400-year persecution in the Roman Empire by encouraging them to stay away from various heresies. It can be argued, of course, that Emperor Constantine the Great, who publicly recognized Christianity in 313, or Emperor Theodosius I, who declared Christianity as the state religion in 392, was more influential than Augustine. But, Constantine and Theodosius may have used Christianity merely as a means for political unity. By contrast, Augustine's theological teachings as bishop of Hippo were developed after his spiritual conversion from his Hellenistic upbringing and education, and had a more powerful and lasting influence. Especially his defense of Christianity from those pagan accusations of it which were occasioned by Alaric's sack of Rome in 410, as seen in The City of God, his major work, has been influential because it, showing a profound view of providential history, has given Augustine an image of true defender and even liberator of the Christians.

His theology, however, has received various criticisms. At least three of them are major ones, and one can defend him from them in fairness to him:

- The first major criticism is that his theological thinking, when combining Christianity with philosophical tools, is many times not as articulate and systematic. This can be addressed by understanding that Augustine as a Platonist was seeking "wisdom" (sapientia) from the subsisting ideas in God prior to any "knowledge" (scientia) of temporal things in the world. He was thus presenting broad theological and philosophical themes based on wisdom rather than exact positions.

- The second one usually is that Augustine started, in an authoritarian way, the tradition of using force to bring back heretics. But, a careful reading of all his anti-Donatist writings would show that that criticism may not be as persuasive. Augustine apparently understood the use of force to be based on love, although it can be said that unfortunately the Church later ended up abusing it without a sense of love.

- The third major one is that his doctrine of predestination in its distinction between the elect and the reprobate would present a merciless God for the reprobate. But, this criticism usually stems from a misunderstanding of Augustine's real position, which, as has been seen above, does reconcile predestination and free will through divine foreknowledge, and which therefore can theoretically secure the possibility of the salvation of the reprobate. It is quite important to know that Augustine's doctrine of predestination is different from the predestinarianism of Calvin.

Some of the other criticisms constitute points of debate even today:

- First of all, Augustine's view of evil as non-being, which much of the Christian tradition has accepted, may not be able to explain the virulent reality of evil in which evil is experienced as substantially so powerful as to injure and kill people as in the Holocaust. Many people including the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, therefore, have disagreed with Augustine's non-being theme of evil. Common sense tells us that when a knife, for example, is used to murder someone, it actually exerts a substantial force of evil, but that when it is used to peel an apple, it exerts a substantial force of goodness. So, while the knife itself as a being seems to be neither good nor evil, its becoming substantially good or evil is determined by a purpose or direction for which it is used. So, Augustine's thesis that the knife itself as a being is good, and that evil is simply the privation of its being with respect of measure, form, and order, which is non-substantial, seems not to be able to explain our actual experiences properly.

- Second, his doctrine of free will, which attributes the possibility of moral evil only to free will, may have ignored the role of temptation from outside of free will in the act of sinning, thus not recognizing the collaboration of Satan, let alone Satan's enticement of illicit love mentioned by some Church Fathers such as Clement of Alexandria and Ambrose. Given his emphasis on the seriousness of original sin, and given his later description of solidarity within the earthly City, this neglect of any evil influence or temptation is simply inconsistent. The American Social Gospel theologian Water Rauschenbusch criticized this aspect of the Augustinian tradition for treating sin merely as a matter of an individual person's "private transaction," and suggested that instead there are "super-personal forces of evil," although he believed that whether Satan actually exists or not may not be an important issue today.[33]

- Third, Augustine's doctrine of original sin may have come largely from his background of Platonic realism, not being completely biblical. His Platonic realism is evident in his assertion that when Adam fell, all his descendents also fell because of their close ontological connection with him through the common essence of human nature in which all humans participate. This view of the solidarity of humankind as regards original sin does not have to bring in Satan as the center of original sin, much less what could be called Satan's lineage. Hence, Augustine's explanation of the transmission of original sin has recourse only to concupiscence at best, precluding Paul's biblical notion of the influential power of Satan behind it: "Paul would have rejected Augustine’s idea of biological transmission. Paul presents a scenario in which humanity is held captive by a spirit being who enslaves them to sin (2 Corinthians 4:4–6; Ephesians 2:1–2). According to Paul, the entire world is held captive to 'the prince of the power of the air,' or Satan."[34]

- Fourth, Augustine's doctrine of marriage, which prefers virginity to marriage, may not have appreciated the goodness of marriage enough perhaps because of his Platonic dualism which does not appreciate matter or flesh as much. His emphasis on the problem of concupiscence after Adam's fall is understandable. But, if male and female humans were both created in the image of God, it may be argued that marriage without concupiscence is a real possibility in a restored realm of "original righteousness." Marriage is a popular subject of discussion in Christianity today, presenting a more positive view bridging spirituality and sexuality. Married priesthood is a controversial and more widespread topic of discussion in Catholicism today. But, Augustine's doctrine of marriage seems not to be able to provide any new answers.

- Fifth, Augustine's view of the City of God as in heaven and not on the earth has often been questioned. Weren't many earlier Church Fathers such as St. Irenaeus, who were combating the otherworldly heresy of gnosticism, expecting God's kingdom to come on the earth, because God had promised the earth to Abraham? So, it can be said that when King Charlemagne, who reportedly loved to read Augustine's The City of God, mistakenly assumed that it was referring to God's kingdom on the earth, his mistake made sense.

- Sixth, as was already discussed above, Augustine may have too sharply contrasted between time and eternity, and therefore between the changeable realm of creation and the unchangeable realm of God. It is not only the Neo-Thomist philosopher Etienne Gilson but also Whiteheadian philosophers that have criticized this point. One simple question: If God creates a world sharply separated from himself, can it be his real partner of love to communicate with? Or, is the purpose of creation simply for him to stay aloof from the world?

- In sum, it can be said that Augustine's Platonic and/or Neoplatonic bias gave rise to elements of inadequacy in his views on various subjects such as evil, free will, original sin, marriage, the City of God, and time and eternity, although there is no doubt that this bias also constituted a positive contribution to the formation of his profound theology.

Writings

Books

- On Christian Doctrine, 397-426 C.E.

- Confessions, 397-398

- The City of God, begun c. 413, finished 426

- On the Trinity, 400-416

- Enchiridion

- Retractions

- At the end of his life (c. 426-428) Augustine revisited his previous works in chronological order and suggested what he would have said differently in a work titled the Retractions, giving the reader a rare picture of the development of a writer and his final thoughts.

- The Literal Meaning of Genesis

- On Free Choice of the Will

Letters

Numerous.

See also

- Predestination

- Free will

- Pelagianism

- Constantinian shift

- Filioque

- Scholasticism

- Truth

Notes

- ↑ Augustine, The Confessions, book 8, chap. 7, sec. 17.Translated by J.G. Pilkington. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 1, Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1887.) newadvent.org. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ↑ F. A. Wright and T. A. Sinclair. A History of Later Latin Literature. (London, 1931), 56 ff.

- ↑ Augustine, "On the Morals of the Manichaeans," chap. 2, sec. 2. translated by the Rev. Richard Stothert. newadvent.org. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "On the Morals of the Manichaeans," chap. 8, sec. 11. translated by the Rev. Richard Stothert. newadvent.org. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "On Baptism, Against the Donatists." newadvent.org. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "The Correction of the Donatists," chap. 6, sec. 24. newadvent.org. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ↑ For example, Theodore Shimmyo, "St. Augustine’s Treatment of the Donatist Controversy," The Patristic & Byzantine Review 10 (1991): 173-182

- ↑ J.R. King, "Preface" to Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series I/Volume IV/Donatist Controversy. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "The Correction of the Donatists," chap. 6, sec. 22; chap. 8, sec. 33. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "On Grace and Free Will," chap. 33. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "On Marriage and Concupiscence." Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ↑ Eugène Portalié, A Guide to the Thought of St. Augustine (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1960), 204-13.

- ↑ Augustine, "On Marriage and Concupiscence," book 1, sec. 27. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "On Rebuke and Grace," chap. 39. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "On the Predestination of the Saints," book 2, chap. 42.newadvent.org.

- ↑ The Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v., "Predestinarianism."newadvent.org. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, On the Trinity, book 7, chap. 4, sec. 8. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, On the Trinity, book 12, chap. 15, sec. 24. newadvent.org. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, On the Trinity, book 12, chap. 12, sec. 2. newadvent.org. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine. The Literal Meaning of Genesis, trans. John Hammond Taylor, vol. 1 (New York: Newman Press, 1982), 42-43.

- ↑ Augustine, The City of God, book 11, chap. 6. newadvent.org. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, The Confessions, book 11, chap. 31, sec. 41. newadvent.org. Retrieved May, 16, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "Concerning the Nature of Good, Against the Manichaeans," chap. 1.newadvent.org. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "Concerning the Nature of Good, Against the Manichaeans," chaps. 1, 10, and 27. newadvent.org. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, The City of God, book 14, chap. 28.Translated by Marcus Dods. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 2. Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1887.) newadvent.org. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, The City of God, book 15, chap. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2008]

- ↑ Augustine, "Reply to Faustus the Manichaean," chap. 22, sec. 75. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, "Reply to Faustus the Manichaean," chap. 22, sec. 74. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ Augustine, The City of God, book 18, chap. 46. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ↑ John Y.B. Hood, Aquinas and the Jews (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995); and Paula Fredriksen, Augustine and the Jews: A Christian Defense of Jews and Judaism (Doubleday, 2008).

- ↑ Thomas Cahill. How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland's Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe. (Bantam-Doubleday-Dell, 1995), 39.

- ↑ Kenneth Richard Samples, "Historical Profile: Augustine of Hippo Part 1 of 2: From Pagan, to Cultist, to Skeptic, to Christian Sage," Facts For Faith 5 (2001): 36-41.

- ↑ Walter Rauschenbusch. A Theology of Social Gospel. (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1978).

- ↑ Peter Nathan, "The Original View of Original Sin," Vision (Summer 203).

Bibliography

- Battenhouse, Roy W., ed. A Companion to the Study of St. Augustine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1955.

- Bourke, Vernon J. Wisdom from St. Augustine. Houston, Texus: Center for Thomistic Studies, 1984. ISBN 0268019347

- Brown, Peter. Augustine of Hippo. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967. ISBN 0520001869

- Cahill, Thomas. How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland's Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe. Bantam-Doubleday-Dell, 1995. ASIN: B000P3YD0K

- Fitzgerald, Allan D., ed. Augustine Through the Ages: An Encyclopedia. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1999. ISBN 080283843X

- Fredriksen, Paula. Augustine and the Jews: A Christian Defense of Jews and Judaism. Doubleday, 2008. ISBN 0385502702

- Hood, John Y.B. Aquinas and the Jews. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995. ISBN 0812215230

- King, J.R., "Preface" to Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Series I/Volume IV/Donatist Controversy. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- Matthews, Gareth B. Augustine. Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 0631233482

- O'Donnell, James J. Augustine: A New Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 0060535377

- Portalie, Eugene. A Guide to the Thought of St. Augustine. Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1960.

- Pottier, René. Saint Augustin le Berbère. Fernand Lanore, 2006. ISBN 2851572822

- Plumer, Eric Antone. Augustine's Commentary on Galatians. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0199244391. Preview from Google. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- Rauschenbusch, Walter. A Theology of Social Gospel. (original 1917) reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2008. ISBN 1436559928

Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1978.

- Ruickbie, Leo. Witchcraft Out of the Shadows. London: Robert Hale, 2004. ISBN 0709075677

- Samples, Kenneth Richard. "Historical Profile: Augustine of Hippo Part 1 of 2: From Pagan, to Cultist, to Skeptic, to Christian Sage." Facts For Faith 5 (2001): 36-41.

- Shimmyo, Theodore. "St. Augustine’s Treatment of the Donatist Controversy." The Patristic & Byzantine Review 10 (1991): 173-182

- Tanquerey, Adolphe. The Spiritual Life: A Treatise on Ascetical and Mystical Theology. Rockford, IL: Tan Books, 2000 (original 1930). ISBN 0895556596

- von Heyking, John. Augustine and Politics as Longing in the World. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2001. ISBN 0826213499

- Zumkeller, Adolar. Augustine's Ideal of Religious Life. New York: Fordham University Press,1986. ISBN 0823211053

- Zumkeller, Adolar. Augustine's Rule. Villanova, PA: Augustinian Press, 1987. ISBN 0941491064

External links

All links retrieved August 21, 2023.

- General:

- Saint Augustine – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Augustine of Hippo – EarlyChurch.org.uk

- Life of St. Augustine of Hippo – Catholic Encyclopedia

- Articles on Augustine's Theology:

- Oakes, Edward T. "Original Sin: A Disputation."

- Sproul, R. C. "Augustine and Pelagius."

- Texts by Augustine:

- St. Augustine – Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

- Augustinius – IntraText Digital Library.

- The Latin Library: Books and Letters by Augustine.

- Documenta Catholica Omnia – Augustine’s works in Latin, Italian, English.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.