A conscientious objector (CO) is a person refusing to bear arms for their country, for reasons based on their conscience. They may have religious, moral, or ethical beliefs incompatible with being a combatant in military service, or they may refuse to be a part of any combatant organization. In the first case, conscientious objectors may be willing to accept non-combatant roles during conscription or military service. In the second case, the objection is to any role within armed forces and results in complete rejection of conscription or military service and, in some countries, assignment to an alternative civilian service as a substitute.

Historically, conscientious objection was not an issue as those called to military duty were often able to find a substitute to serve in their place. In more recent times, however, such substitution became no longer acceptable, and many people, not lacking in physical strength or courage, found themselves at odds with their conscience regarding their duty to serve their country in times of war. This reflects a growing awareness that human life is sacred, and that violence does not lead to the world of peace and harmony desired by all.

Introduction

Conscientious objection (CO) to military service has existed for centuries. It generally refers to the refusal to bear arms or participate in military training during wartime, based on one's conscience.

Historically, many conscientious objectors were executed, imprisoned, or sanctioned when their beliefs led to actions conflicting with their society's legal system or government. The legal definition and status of conscientious objection has varied over the years and from nation to nation. Religious beliefs were a starting point in many nations for legally granting conscientious objection status. However, acceptable grounds have broadened beyond religion in many countries.

In 1971, a United States Supreme Court decision broadened U.S. rules beyond religious belief but denied the proposed inclusion of objections to specific wars as grounds for conscientious objection.[1] Proponents of the objection to specific wars had distinguished between wars of offensive aggression and defensive wars, while others contended that religious, moral, or ethical opposition to war need not be absolute or consistent but may depend on circumstance or political conviction.

The definition of qualification according to the U.S. Selective Service System (SSS) is as follows:

Beliefs which qualify a registrant for conscientious objector status may be religious in nature, but don't have to be. Beliefs may be moral or ethical; however, a man's reasons for not wanting to participate in a war must not be based on politics, expediency, or self-interest. In general, the man's lifestyle prior to making his claim must reflect his current claims.[2]

In the U.S., this applies to primary claims, that is, those filed on initial SSS registration. On the other hand, those who apply after either having registered without filing, and/or having attempted or effected a deferral, are specifically required to demonstrate a discrete and documented "change" in belief, including a precipitant, that converted a non-CO to a CO. The male reference is due to the "male only" basis for conscription in the United States.

Historically, it was often not necessary to refuse to serve in the military. Within the Roman Empire avoiding military service was not a problem, because the legions and other armed forces were largely composed of volunteers. Some legionaries who converted to Christianity were able to reconcile warfare with their Christian beliefs, as formalized in the Just War theory. In the eleventh century, there was a further shift of opinion with the crusades strengthening the idea and acceptability of Holy War.

Feudalism imposed various forms of military obligation, before and after the crusading movement (which was composed of volunteers). However, since the demand was to send someone rather than any particular person, those who did not wish to fight, for whatever reason, were left alone if they could pay or persuade someone else to go in their place.

Motives

The reasons for refusing to serve are varied. Many conscientious objectors do so for religious reasons. Members of the Historic Peace Churches are pacifist by doctrine. Jehovah's Witnesses, while not pacifist in the strict sense, refuse to participate in the armed services on the grounds that they believe Christians should be neutral in worldly conflicts. Other objections can stem from a deep sense of responsibility toward humanity as a whole, or from simple denial that any government should have that kind of moral authority.

Because of their conscientious objection to participation in military service, whether armed or unarmed, Jehovah's Witnesses have often faced imprisonment or other penalties. In Greece, for example, before the introduction of alternative civilian service in 1997, hundreds of Witnesses were imprisoned, some for three years or even more for their refusal. In Armenia, young Jehovah's Witnesses have been imprisoned because of their conscientious objection to military service. On the other hand, in Switzerland, virtually every Jehovah's Witness is exempted from military service, while the Finnish government exempts Jehovah's Witnesses from the draft completely.

For believers in Dharmic religions, the opposition to warfare may be based on either the general idea of ahimsa, non-violence, or on an explicit prohibition of violence by their religion. For a Buddhist, one of the five precepts is "Pānātipātā veramaṇi sikkhāpadam samādiyāmi," or "I undertake the precept to refrain from destroying living creatures," which is in obvious opposition to the practice of warfare. The fourteenth Dalai Lama, the highest religious authority in Tibetan Buddhism, has stated that war "should be relegated to the dustbin of history." On the other hand, many Buddhist sects, especially in Japan, have been thoroughly militarized, with warrior monks (yamabushi or sóhei) participating in civil wars.

Some practitioners of pagan religions, particularly Wicca, may object on the grounds of the Wiccan rede, which states "An it harm none, do what ye will" (or variations). The threefold law may also be grounds for objection.

The motivations for objecting to a war may be subtle and difficult to apply across wars; not all who object are complete pacifists. Many also object to wars for political reasons. One famous example is that of boxer Muhammad Ali who when drafted for the Vietnam War famously declared, "Man, I ain't got no quarrel with them Vietcong."[3] Ali's comments highlight the subtle area of self defense. Many Americans refused to participate in the Vietnam War because they believed it had nothing to do with defending the United States. The will to fight for self defense is questioned during conscientious objector hearings, but determining what is a legitimate act of self defense on the part of the armed forces is difficult in situations such as the Vietnam War, which was undertaken to defend broader ideological aims.

Hearings about the state of the conscience

The nature of hearings to establish conscientious objector status vary from country to country. In the United States, military personnel who come to a conviction of conscientious objection during their tour of duty must appear in front of a panel of experts, which consists of psychiatrists, military chaplains, and officers. In Switzerland, the panel consists entirely of civilians, and military personnel have no authority whatsoever.

In Germany, objections to military service are filed in writing, and an oral hearing is scheduled only if the written testimonials have been unconvincing; in practice, due to the heavy workload—about half of all draftees in a given year file memorials as conscientious objectors—the competent authority reviews written applications only summarily, and it denies the alternative of a civilian service only in cases of grave shortcomings or inconsistencies in the written testimonials. Commonly, once an objector is summoned to a hearing, he has to explain what experiences drove him to recognize a conflict concerning his conscience.

Common questions at hearings

The following are common questions from Swiss hearings. By and large, these are asked in many other countries.

- In general: How and when did you decide against the military service? Why can't you arrange military service with your conscience? What prohibits you to serve in the military?

- Military service: Do you fear having to fight, or to use force? Do you want to abolish the army? What do you think about the phrase "We have the army to defend us, not to kill others"?

- Use of force: What would you do if you were attacked? What do you feel when you see that others are attacked? What is violence, exactly? Would you rather experience losses than having to use force?

- Belief: What does your belief say? Would you describe yourself as a pacifist? What basic values, besides objecting to violence, do you have? What entity gives you the certainty that your thinking and your feelings are right?

- Implementation of your beliefs: Why didn't you choose to go into prison if your conscience is that strong? Why didn't you use medical reasons to avoid military service? What do you actually do to further peace, or is your attitude the only peaceful thing about you?

- Personality: Who is in charge of defending your children in case of an armed conflict? Do you live your ethical principles inside your family? What books do you read? What do you demand from yourself? Are you merely a leader, a follower or a loner?

The questions are designed to determine if the objector is politically motivated or if he is just too lazy to serve the country; or if he truly has a conflict stemming from his conscience. Arguments like "The army is senseless," "It is not just to wage wars," or opposition to involvement in a specific war (World War II, the Vietnam War, the Iraq War; a hypothetical war of West Germany against fellow Germans from the GDR during the Cold War) will hardly ever be accepted. The objector has only, and convincingly, to show that his conscience does not allow participation in an organization which is intended to use violence.

Alternatives for objectors

Some conscientious objectors are unwilling to serve the military in any capacity, while others accept noncombatant roles. Alternatives to military or civilian service include serving an imprisonment or other punishment for refusing conscription, falsely claiming unfitness for duty by feigning an allergy or a heart condition, delaying conscription until the maximum drafting age, or seeking refuge in a country which does not extradite those wanted for military conscription.

Avoiding military service is sometimes labeled "draft dodging," particularly if the goal is accomplished through dishonesty or evasive maneuvers. However, many people who support conscription will distinguish between bona fide "conscientious objection" and "draft dodging," which they view as evasion of military service without a valid excuse.

United States of America

During the American Revolutionary War exemptions varied by state. Pennsylvania required conscientious objectors, who would not join companies of voluntary soldiers called Associations, to pay a fine roughly equal to the time they would have spent in military drill.[4] Quakers who refused this extra tax had their property confiscated.

The first conscription in the United States came with the Civil War. Although conscientious objection was not part of the draft law, individuals could provide a substitute or pay $300 to hire one.[5] By 1864, the draft act allowed the $300 to be paid for the benefit of sick and wounded soldiers. Conscientious objectors in Confederate States initially had few options. Responses included moving to northern states, hiding in the mountains, joining the army but refusing to use a weapon, or imprisonment. Between late 1862 and 1864 a payment of $500 into the public treasury exempted conscientious objectors from Confederate military duty.[6]

|

We were cursed, beaten, kicked, and compelled to go through exercises to the extent that a few were unconscious for some minutes. They kept it up for the greater part of the afternoon, and then those who could possibly stand on their feet were compelled to take cold shower baths. One of the boys was scrubbed with a scrubbing brush using lye on him. They drew blood in several places. Mennonite from Camp Lee, Virginia, United States, 16 July 1918.[7] |

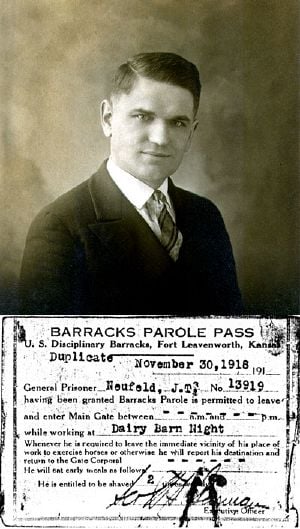

In the United States during World War I, conscientious objectors were permitted to serve in noncombatant military roles. About 2,000 absolute conscientious objectors refused to cooperate in any way with the military.[8] These men were imprisoned in military facilities such as Fort Lewis (Washington), Alcatraz Island (California), and Fort Leavenworth (Kansas). The government failed to take into account that some conscientious objectors viewed any cooperation with the military as contributing to the war effort. Their refusal to put on a uniform or cooperate in any way caused difficulties for both the government and the COs. The mistreatment received by these absolute COs included short rations, solitary confinement, and physical abuse so severe as to cause the deaths of two Hutterite draftees.[9]

Eventually, because of the shortage of farm labor, the conscientious objectors were granted furloughs either for farm service or relief work in France under the American Friends Service Committee. A limited number performed alternative service as fire fighters in the Cascade Range in the vicinity of Camp Lewis, Washington[10] and in a Virginia psychiatric hospital.[11]

Civilian Public Service (CPS) provided conscientious objectors in the United States an alternative to military service during World War II. From 1941 to 1947, nearly 12,000 draftees, unwilling to do any type of military service, performed "work of national importance" in 152 CPS camps throughout the United States and Puerto Rico. The work was initially done in areas isolated from the general population both because of the government's concern that pacifist philosophy would spread and that conscientious objectors would not be tolerated in neighboring communities. A constant problem for this program was to design appropriate work to occupy the men's time in the off-season and between fires. For instance, men at a camp on the Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia shoveled snow from an unused roadway while a snowplow was parked nearby. The uselessness of this type of work led to low morale and loss of experienced men as they requested transfers to other camps hoping for more meaningful work. Draftees from the historic peace churches and other faiths worked in areas such as soil conservation, forestry, fire fighting, agriculture, social services, and mental health.

The CPS men served without wages and minimal support from the federal government. The cost of maintaining the CPS camps and providing for the needs of the men was the responsibility of their congregations and families. CPS men served longer than regular draftees, not being released until well past the end of the war. Initially skeptical of the program, government agencies learned to appreciate the men's service and requested more workers from the program. CPS made significant contributions to forest fire prevention, erosion and flood control, medical science, and especially in revolutionizing of the state-run mental health institutions which had previously been cruel and inhumane.

The Civilian Public Service was disbanded in 1947. By the early 1950s a replacement program, 1-W service, was in place. 1-W service was divided into several categories. The Earning Service involved working in institutions such as hospitals for fairly good wages. Voluntary Service was nonpaying work done in similar institutions, mostly within North America. Pax Service was a nonpaying alternative with assignments overseas. 1-W Mission Supporting Service was like the Earning Service but the wages were used for the support of mission, relief, or service projects of the draftees' choice. The nonpaying services were promoted by church agencies as a sacrifice to enhance the peace witness of conscientious objectors.[12]

Canada

Mennonites in Canada were automatically exempt from any type of service during World War I by provisions of the Order in Council of 1873. With pressure of public opinion, the Canadian government barred entry of additional Mennonite and Hutterite immigrants, rescinding the privileges of the Order in Council. During World War II, Canadian conscientious objectors were given the options of noncombatant military service, serving in the medical or dental corps under military control, or working in parks and on roads under civilian supervision. Over 95 percent chose the latter and were placed in Alternative Service camps. Initially the men worked on road building, forestry, and firefighting projects. After May 1943, as the labor shortage developed within the nation, men were shifted into agriculture, education, and industry. The 10,700 Canadian objectors were mostly Mennonites (63 percent) and Doukhobors (20 percent).[13]

Eastern Europe

Tsarist Russia allowed Russian Mennonites to run and maintain forestry service units in South Russia in lieu of their military obligation. The program was under church control from 1881 through 1918, reaching a peak of 7,000 conscientious objectors during World War I. An additional 5,000 Mennonites formed complete hospital units and transported wounded from the battlefield to Moscow and Ekaterinoslav hospitals.[14]

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Leon Trotsky issued a decree allowing alternative service for religious objectors whose sincerity was determined upon examination. Vladimir Tchertkov, a follower of Leo Tolstoy, chaired United Council of Religious Fellowships and Groups, which successfully freed 8,000 conscientious objectors from military service during the Russian Civil war. However, the law was not applied uniformly and hundreds of objectors were imprisoned and over 200 executed. United Council was forced to cease activity in December 1920, but alternative service was available under the New Economic Policy until it was abolished in 1936.[15] Unlike the earlier forestry and hospital service, later conscientious objectors were classified "enemies of the people" and their alternate service was performed in remote areas in a forced labor, concentration camp environment in order to break their resistance and encourage enlistment.[16]

In Czechoslovakia those not willing to enter mandatory military service could avoid it by signing a contract for work lasting several years in unattractive occupations, such as mining. Those who refused to sign were punished by imprisonment. After the Communist party lost power in 1989, alternative civil service was established. Later, both the Czech Republic and Slovakia abolished conscription.

Western Europe

United Kingdom

Great Britain's armed services had for centuries been all-volunteer forces—though press gangs took sailors for the Royal Navy in the Napoleonic War. In World War I, Britain introduced conscription with the Military Service Act of 1916. This meant that objections on religious or ethical grounds became an issue. Of those "called up," about 16,000 refused to fight. Quakers, traditionally pacifist, played a large role.[17] Many objectors accepted non-combat service. Some worked as stretcher-bearers, which was dangerous even though no one intentionally shot at them.

Conscientious objectors had to prove their right not to fight:

8,608 appeared before Military Tribunals. Over 4,500 were sent to do work of national importance such as farming. However, 528 were sentenced to severe penalties. This included 17 who were sentenced to death (afterwards commuted), 142 to life imprisonment, three to 50 years' imprisonment, four to 40 years and 57 to 25 years. Conditions were made very hard for the conscientious objectors and sixty-nine of them died in prison.[18]

In World War II, there were nearly 60,000 registered conscientious objectors. Tests were much less harsh—it was generally enough to say that you objected to "warfare as a means of settling international disputes," a phrase from the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928. Objectors were required to do work that was either war-related or classified as "useful." Conscription was continued (as National service) until 1960.

Finland

Finland introduced conscription in 1881, but its enforcement was suspended as part of Russification in 1903. During the Finnish Civil War in 1918, conscription was reintroduced, and it was mandatory for all able-bodied Finnish males. In 1922, non-combatant military service was allowed, but those who refused to serve in the military were imprisoned. Only after the struggle of Arndt Pekurinen was a law of alternative non-military service during peacetime introduced, in 1931. However, the law applied only to peacetime. After the beginning of the Winter War in 1939, Pekurinen and other conscientious objectors were imprisoned immediately as they were considered dangerous to national security. At the outbreak of the Continuation War in 1941, Pekurinen was sent to the front lines. At the front, he still refused to wear a uniform or carry arms and was executed without trial.

After World War II, the tour of duty for conscientious objectors was twice the length of the shortest conscription, 16 months. The objectors had to prove their conviction, and should they fail to do so, they were forced to serve in the armed service. The period was shortened to 13 months in 1987. At the same time the conviction inspection board was abolished. This alternative service still only applies during times of peace; there is no exclusion from service during wartime.

Germany

According to Article 12a of the German constitution (Grundgesetz), every adult man can be obligated to military service (Wehrdienst). The draftee can apply for an alternative service Zivildienst (civilian service), if he declares reasons of conscience. Since October 1, 2004, civilian service does not last longer than military service. Before that date civilian service was longer than military service, because soldiers could later be called to military exercises (Wehrübungen). In wartime, civilian draftees are expected to replace those on active military duty in their civilian professions.

Those fulfilling their service in the nursing or social service domain bear a large part of the workload. It is believed that abolishing the draft—and with that, the compulsory civil service for objectors—would plunge hospitals and and other facilities into severe trouble.

Italy

Until 2004, conscription was mandatory to all able-bodied Italian males. Those who were born in the last months of the year typically served in the Navy unless judged unable for ship service (in which case they could be sent back to Army or Air Force). Until 1972, objectors were considered as traitors and tried by a Military Court. Since 1972, objectors could choose an alternative service the length of which was 8 months longer than the military service. Since the length was judged too punitive, a later arrangement was made to reduce the maximum length of the civilian service to 13 months. Since 2004, conscientious objector status became unnecessary because military service is solely volunteer for both males and females.

Spain

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 acknowledged conscientious objectors, with the establishment of a longer civilian service (Prestación Social Sustitoria) as an alternative to the Army. The Red Cross has been the only important organization that employed objectors, resulting in long waiting lists for the PSS, especially in areas like Navarre, where pacifism, Basque nationalism, and a low unemployment rate discouraged young males from the army.

South Africa's anti-war experience

During the 1980s, hundreds of South African "white" males objected to conscription in the South African Defence Force. Some simply deserted, or joined organizations such as the End Conscription Campaign, an anti-war movement banned in 1988; others fled into exile and joined the Committee on South African War Resistance. Most lived in a state of internal exile, forced to go underground within the borders of the country until a moratorium on conscription was declared in 1993.

Turkey

The issue of conscientious objection is highly controversial in Turkey. Turkey and Azerbaijan are the only two countries refusing to recognize conscientious objection in order to sustain their membership in the Council of Europe. In January 2006, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) found Turkey had violated article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (prohibition of degrading treatment) in a case dealing with conscientious objection.[19] In 2005, Mehmet Tarhan was sentenced to four years in a military prison as a conscientious objector (he was unexpectedly released in March 2006). Journalist Perihan Magden was tried by a Turkish court for supporting Tarhan and advocating conscientious objection as a human right; but later she was acquitted.

Israel

Israel has a long history of individuals and groups refusing military service since the state's foundation in 1948. During the country's first decades this involved mainly a few isolated individuals, usually pacifists, due to pervasive public feeling that the country was fighting for its survival and that the IDF was a "Defense Force" in fact as well as in name.

The view of the IDF as an army of defense came into serious question only following the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967, when the army took up the job of keeping a sizable Palestinian population under Israeli rule by force, often involving what were perceived by a considerable number of Israelis as violations of human rights. Moreover, a growing amount of the troops' time and energy was devoted to the safeguarding of an increasing number of settlements erected on formerly-Palestinian land, acquired in ways which many in the Israeli society considered highly questionable.

The invasion of Lebanon in 1982 precipitated a mass anti-war movement, of which a major component was an organized movement by thousands of soldiers (especially reserve soldiers) refusing service in Lebanon. This was continued during the First Intifada, the Second Intifada, and the Second Lebanon War of 2006, and becoming a permanent feature of Israeli social and political life.

While some of the individuals and groups involved fit the definition of Conscientious Objection common in other countries, the phenomenon of "selective refusal"—soldiers who remain inside the army but refuse particular orders or postings, especially to Lebanon or the Occupied Territories—has been widespread in Israel. A longstanding debate continues, of which there is no definitive conclusion, on whether or not this constitutes Conscientious Objection in the strict sense or should be treated as a separate phenomenon.

The situation today

While conscientious objectors used to be seen as deserters, traitors, cowards, slackers, or simply un-patriotic, their image changed drastically in the twentieth century. Especially in Europe, where objectors usually serve an alternative civilian service, they are regarded as making an important contribution to society. Parallel to that, the number of objectors has risen significantly. For example, in Germany, where conscientious objection is a constitutional right, it rose from less than one percent of all eligible men to more than fifty percent in 2003.

Despite the fact that international institutions like the United Nations (UN) and the Council of Europe (CoE) regard and promote conscientious objection as a human right, at the beginning of the twenty-first century it still did not have a legal basis in many countries. Among the countries with conscription, in 2004 only thirty countries had some legal provisions for CO status, 25 of them in Europe. In many countries outside Europe, especially in armed conflict areas such as Israel, Palestine, and the Congo, conscientious objection continues to be punished severely.

Notes

- ↑ Gillette v. United States, 401 U.S. 437

- ↑ Selective Service

- ↑ The Nation, Muhammad Ali: The Brand. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ↑ Gingerich p. 2.

- ↑ Gingerich p. 3.

- ↑ Gingerich p. 4.

- ↑ Gingerich p. 10.

- ↑ Gingerich p. 11.

- ↑ Hallock.

- ↑ Gingerich p. 147.

- ↑ Gingerich p. 213.

- ↑ Pannabacker pp. 260-269.

- ↑ Krahn, pp. 76-78.

- ↑ Smith, p. 311.

- ↑ Abraham Braun, Th. Block, and Lawrence Klippenstein, [Forsteidienst, Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online.] Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- ↑ Smith, p. 330.

- ↑ Quaker.org, Quakers in Britain. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ↑ Spartacus Education Pacifism page

- ↑ European Court of Human Rights, "Chamber Judgement Ulke vs. Turkey." Accessed June 7, 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bennett, Scott H. 2003. Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915-1963. Syracuse Univ. Press.

- Bennett, Scott H. 2005. Army GI, Pacifist CO: The World War II Letters of Frank and Albert Dietrich. Fordham Univ. Press.

- Gingerich, Melvin. 1949. Service for Peace, A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Mennonite Central Committee.

- Hallock, Dan. The Martyrs of Alcatraz;Religious Persecution in the Land of the Free. Bruderhoff Communities Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- Keim, Albert N. 1990. The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service. pp. 75-79. Good Books. ISBN 1-56148-002-9

- Krahn, Cornelius, Gingerich, Melvin & Orlando Harms. (Eds.) 1955. The Mennonite Encyclopedia. Volume I, pp. 76-78. Mennoniite Publishing House.

- Mock, Melanie Springer. 2003. Writing Peace: The Unheard Voices of Great War Mennonite Objectors. Cascadia Publishing House. ISBN 1-931038-09-0

- Pannabecker, Samuel Floyd. 1975. Open Doors: A History of the General Conference Mennonite Church. Faith and Life Press. ISBN 0-87303-636-0

- Selective Service. 2002. Conscientious Objection and Alternative Service: Who Qualifies.

- Smith, C. Henry. 1981. Smith's Story of the Mennonites. Newton, Kansas: Faith and Life Press. ISBN 0-87303-069-9

- Tejada-Flores, Rick and Judith Ehrlich. 2000. "The good war and those who refused to fight it" [videorecording]; Paradigm Productions in association with the Independent Television Service, aired on PBS.

External links

All links retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Alternative Service in the Second World War: Conscientious Objectors in Canada 1939-1945.

- Mennonite Central Committee

- The European Bureau for Conscientious Objection

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.