In biological taxonomy, domain is commonly employed as the highest taxonomic unit, above kingdom, typically involving the division of cellular life into the three domains of Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya (Eucarya), although some proposals call for a two-domain system, Archaea and Bacteria, with Eukarya included in Archaea. Other names which have sometimes been used or suggested for this taxonomic level are dominion, superkingdom, realm, and empire. While the taxonomic level of domain is commonly used, and in particular the tripartite division into three domains, this taxon has not been canonized by international taxonomic committees.

The use of domain as a taxonomic unit aligns with the effort of scientists to elucidate the connectedness of living organisms via descent over time; in the case of the three-domain system, proposing a major divide in the universal phylogenetic tree into the three major groupings.

Overview and history

The three-domain system of taxonomy was proposed by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis in 1990. The key difference from earlier classifications such as the prokaryote-Eukaryote classification and the five-kingdom classification (Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista, and Moneraâthe most widely used at the time) is the splitting of Archaea (previously named "archaebacteria") from Bacteria as completely different organisms. According to Worse et al. (1990):

Neither of the conventionally accepted view of the natural relationships among living systemsâi.e., the five-kingdom taxonomy or the eukaryote-prokaryote dichotomyâreflects this primary tripartite division of the living world. To remedy this situation we propose that a formal system of organisms be established in which above the level of kingdom there exists a new taxon called a "domain." Life on this planet would then be seen as comprising three domains, the Bacteria, the Archaea, and the Eucarya, each containing two or more kingdoms.

They further note:

Chatton c(1938) codified it with his famous eukayote-prokaryote proposal, dividing all life into these two primary categories. This view of life, strangely, has coexisted for some time now with the five-kingdom scheme, despite their basic incompatibility, and despite the fact that the evidence overwhelmingly supports the former. However, the eukaryote-prokaryote concept itself has been seriously misunderstood and, consequently, wrongly interpreted. ... This presumption was then formalized in the proposal that there be two primary kingdoms: Procaryotae and Eucaryotae. It took the discovery of the archaebacteria to reveal the enormity of this mistake.

This term domain represents a synonym for the category of dominion (Lat. dominium), introduced by Moore in 1974.

The proposal of the three-domain system came on the foundation of Carl Woese's revolutionary breakthrough, published in 1977 (Worse et al. 1977; Woese and Fox 1977; Balch et al. 1977), involving comparing the nucleotide sequences of the 16s ribosomal RNA and discovering that the rank, domain, contained three branches, not two like scientists had previously thought. Initially, due to their physical similarities, Archaea and Bacteria were classified together and called "archaebacteria". However, scientists now know that these two domains are hardly similar and are internally wildly different.

Woese argued, on the basis of differences in 16S rRNA genes, that bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes each arose separately from an ancestor with poorly developed genetic machinery, often called a progenote. To reflect these primary lines of descent, he treated each as a domain, divided into several different kingdoms. Originally his split of the prokaryotes was into Eubacteria (now Bacteria) and Archaebacteria (now Archaea) ("Worse and Fox 1977). Woese initially used the term "kingdom" to refer to the three primary phylogenic groupings, and this nomenclature was widely used until the term "domain" was adopted in 1990 (Worse et al. 1990).

Acceptance of the validity of Woese's phylogenetically classification was a slow process. Prominent biologists including Salvador Luria and Ernst Mayr objected to his division of the prokaryotes (Mayr 1998; Sapp 2007). Mayr (1998) did recognize Worse's contribution of identifying a major division in the prokaryotes:"By far his [Worse's] most important discovery was that the prokaryotes actually consist of two major groups: (i) the traditional bacteria ... and(ii) a previously unrecognized group of bacteria, names by Worse archaebacteria" (which, Mayr notes, were subsequently renamed by Worse as Archaea). But Mayr also notes:

I cannot see any merit at all in a three empire cladification. ... The evidence presented by me shows clearly that the archaebacteria are so much more similar to the eubacteria than to the eukaryotes that their removal from the prokaryotes isnot justified. ... Only a two-empire classification correctly reflects this structure of the living world."

The growing amount of supporting data led the scientific community to accept the Archaea by the mid-1980s (Sapp 2009). Today, very few scientists still accept the concept of a unified Prokarya (Koonin 2014).

The three-domain system has been challenged by the two-domain system that divides organisms into Bacteria and Archaea only, with Eukaryota having branched off from the domain Archaea, and thus eukaryotes considered as a clade of Archaea (GabaldĂłn 2021; Nobs et al. 2022; Doolittle 2020). Another alternatives to the three-domain system include the earlier-mentioned two-empire system (with the empires Prokaryota and Eukaryota),

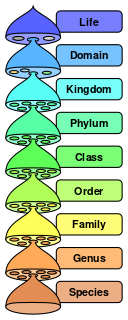

Non-cellular life, most notably the viruses, is not included in this system. Van der Gulik et al. (2023) have proposed adding another level above domain, World (Latin alternative mundis) to include non-cellular entities (as well as the rank of EmpireâLatin alternative imperiumâto accommodate the uncovered diversity in unicellular eukaryotes). Under their proposal, there would be two groups within the taxonomic rank of World: a world of cells and a world of viruses. There proposal would result in a ten-rank system: species, genus, family, order, class, phylum, kingdom, empire, domain, and world.

Van der Gulik et al. (2023) note that the taxonomic rank of domain "was never canonized by international taxonomic committees."

Characteristics of the three domains

The three-domain system adds a level of classification (the domains) "above" the kingdoms present in the previously used five- or six-kingdom systems. This classification system recognizes the fundamental divide between the two prokaryotic groups, insofar as Archaea appear to be more closely related to eukaryotes than they are to other prokaryotes â bacteria-like organisms with no cell nucleus. The three-domain system sorts the previously known kingdoms into these three domains: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya.

Each of these three domains contains unique ribosomal RNA. This forms the basis of the three-domain system. While the presence of a nuclear membrane differentiates the Eukarya from the Archaea and Bacteria, both of which lack a nuclear envelope, the Archaea and Bacteria are distinct from each other due to differences in the biochemistry of their cell membranes and RNA markers (Woese et al. 1990).

Archaea

Domain Archaea [Greek adjective áŒÏÏαáżÎ± (ancient, primitive)] includes cells that are prokaryotic, with no nuclear membrane, but with biochemistry and RNA markers that are distinct from bacteria. Archaeans typically are characterized by membrane lipids that are branched hydrocarbon chains attached to glycerol by ether linkages. The presence of these ether linkages in Archaea adds to their ability to withstand extreme temperatures and highly acidic conditions, but many archaea live in mild environments. Halophiles, organisms that thrive in highly salty environments, and hyperthermophiles, organisms that thrive in extremely hot environments, are examples of Archaea. The Archaeans possess unique, ancient evolutionary history for which they are considered some of the oldest species of organisms on Earth, most notably their diverse, exotic metabolisms.

Archaea evolved many cell sizes, but all are relatively small. Their size ranges from 0.1Â ÎŒm to 15Â ÎŒm diameter and up to 200Â ÎŒm long. They are about the size of bacteria, or similar in size to the mitochondria found in eukaryotic cells. Members of the genus Thermoplasma are the smallest of the Archaea.

Some examples of archaeal organisms are:

- methanogens â which produce the gas methane

- halophiles â which live in very salty water

- thermoacidophiles â which thrive in acidic high-temperature water

Bacteria

Domain Bacteria [Greek noun f3aKr'pov (small rod or staff)], like Archaea, include organisms that are [[prokaryotic], but this domain consists of cells with bacterial rRNA, no nuclear membrane, and whose membranes possess primarily diacyl glycerol diester lipids. Traditionally classified as bacteria, many thrive in the same environments favored by humans, and were the first prokaryotes discovered; they were briefly called the Eubacteria or "true" bacteria when the Archaea were first recognized as a distinct clade.

Even though bacteria are prokaryotic cells just like Archaea, their cell membranes are are distinct from Archean membranes: They characteristically have none of the ether linkages that Archaea have. They instead have cell membranes made of phospholipid bilayers. Internally, bacteria have different RNA structures in their ribosomes, hence they are grouped into a different category. In the two- and three-domain systems, this puts them into a separate domain.

Cyanobacteria and mycoplasmas are two examples of bacteria. There is a great deal of diversity in the domain Bacteria. That diversity is further confounded by the exchange of genes between different bacterial lineages. The occurrence of duplicate genes between otherwise distantly-related bacteria makes it nearly impossible to distinguish bacterial species, count the bacterial species on the Earth, or organize them into a tree-like structure (unless the structure includes cross-connections between branches, making it a "network" instead of a "tree") (Worse et al. 1990).

Most known pathogenic prokaryotic organisms belong to bacteria. (See Eckburg et al. 2003 for examples of Archaea and their potential role in human disease.) For that reason, and because the Archaea are typically difficult to grow in laboratories, Bacteria are currently studied more extensively than Archaea.

Some examples of bacteria include:

- "Cyanobacteria" â photosynthesizing bacteria that are related to the chloroplasts of eukaryotic plants and algae

- Spirochaetota â Gram-negative bacteria that include those causing syphilis and Lyme disease

- Actinomycetota â Gram-positive bacteria including Bifidobacterium animalis which is present in the human large intestine

Eukarya

Domain Eukarya [from the Greek Δᜠ(eu, "well" or "good") and ÎșÎŹÏÏ ÎżÎœ (karyon, "nut" or "kernel", here meaning "nucleus"] includes organisms (called eukaryotes) with membrane-bound organelles (including a nucleus containing genetic material) and commonly are represented by five kingdoms: Plantae, Protozoa, Animalia, Chromista, and Fungi.

The domain contains, for example:

- Holomycota â mushrooms and allies

- Viridiplantae â green plants

- Holozoa â animals and allies

- Stramenopiles â includes brown algae

- Amoebozoa â solitary and social amoebae

- Discoba â includes euglenoids

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Balch, W. E., L. J. Magrum, G. E. Fox, R. S. Wolfe, and C. R. Woese. 1977. An ancient divergence among the bacteria. Journal of Molecular Evolution 9(4): 305â311. PMID 408502.

- Chatton, E. 1938. Titres et Travoux Scientifiques (1906-1937) de Edouard Chatton (E. Sottano, Sete, France).

- Cox, C. J., P. G. Foster, R. P. Hirt, S. R. Harris, T. M. Embley, and Martin Embley. 2008. The archaebacterial origin of eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(51): 20356â61. PMID 19073919.

- Doolittle, W. Ford. 2020. Evolution: two domains of life or three?" Current Biology 30(4): R177âR179. PMID 32097647.

- Eckburg, Paul B., Paul W. Lepp, David A. Relman. 2003. Archaea and their potential role in human disease. Infection and Immunity 71(2): 591â596. PMID 12540534.

- GabaldĂłn, Toni. 2021. Origin and early evolution of the eukaryotic cell. Annual Review of Microbiology 75(1): 631â647. PMID 34343017.

- Koonin, Eugene. 2014. Carl Woese's vision of cellular evolution and the domains of life. RNA Biology 11(3): 197-204. PMID 24572480.

- Mayr, Ernst. 1982. The Growth of Biological Thought. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Mayr, E. 1998. Two empires or three? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95(17): 9720-9723.

- Moore, R. T. 1974. Proposal for the recognition of super ranks. Taxon 23(4): 650â652.

- Nobs, Stephanie-Jane, Fraser I. MacLeod, Hon Lun Wong, and Brendan P. Burns. 2022. Eukarya the chimera: eukaryotes, a secondary innovation of the two domains of life?. Trends in Microbiology 30(5): 421â431. PMID 34863611.

- Sapp, Jan A. 2007. The structure of microbial evolutionary theory. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 38(4): 780-95. PMID 18053933.

- Sapp, Jan A. 2009. The New Foundations of Evolution: On the Tree of Life. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-73438-2.

- van der Gulik, Peter T. S., Wouter D. Hoff, and David Speijer. 2023. Reviewing Linnaean taxonomy: a proposal to restructure the highest levels of the Natural System. Biol. Rev. 98: 384-602.

- Woese, C. R. 1998. Default taxonomy: Ernst Mayr's view of the microbial world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95(19): 11043-11046.

- Worse, C. R., W. R. Balch, L. J. Magrum, G. E. Fox, and R. S. Wolfe. 1977. An ancient divergence among the bacteria. Journal of Molecular Evolution 9(4): 305â311. PMID 408502.

- Worse, C. R., and G. E. Fox. 1977. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryote domain: the primary kingdoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 74(11): 5088-5090.

- Woese, C. R., O. Kandler, and M. I. Wheelis. 1990. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87(12): 4576, 4579.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.