Double bass

| ||||||||

|

The double bass, also known as the standup bass, is the largest and lowest pitched bowed string instrument used in the modern symphony orchestra. It is used extensively in Western classical music as a standard member of the string section of symphony orchestras[1] and smaller string ensembles[2]. In addition, it is used in other genres such as jazz, blues, rock and roll, psychobilly, rockabilly, and bluegrass. As with many other string instruments, the double bass is played with a bow (arco) or by plucking the strings (pizzicato).

Origins and history

The double bass is generally regarded as the only modern descendant of the viola da gamba family of instruments, a family which originated in Europe in the fifteenth century. As such, it can be described as a "bass viol."[3]

Before the twentieth century, many double basses had only three strings, in contrast to the five to six strings typical of instruments in the viola da gamba family or the four strings of instruments in the violin family.

The double bass' proportions are dissimilar to those of the violin. For example, it is deeper (the distance from top to back is proportionally much greater than the violin). In addition, while the violin has bulging shoulders, most double basses have shoulders carved with a more acute slope, like members of the viola da gamba family. Many very old double basses have had their shoulders cut or sloped to aid the performance of modern musical techniques. Before these modifications, the design of their shoulders was closer to instruments of the violin family.

The double bass is the only modern bowed string instrument that is tuned in fourths (like viola da gambas), rather than fifths (see Tuning, below).

In his A New History of the Double Bass, Paul Brun asserts, with many references, that the double bass has origins as the true bass of the violin family. He states that, while the exterior of the double bass may resemble the viola da gamba, the internal construction of the double bass is nearly identical to that of other instruments in the violin family, and is very different from the internal structure of viols[4].

Terminology

A person who plays this instrument is called a bassist, double bassist, double bass player, contrabassist, contrabass player, or simply bass player.

The instrument's standard English name, double bass may be derived from the fact that it is approximately twice as large as the cello, or because the double bass was originally used to double the cello part an octave lower. It has also been suggested that the name derives from its viol family heritage, in that it is tuned lower than the standard bass viola da gamba. The name also refers to the fact that the sounding pitch of the double bass is an octave below the bass clef. The name contrabass comes from the instrument's Italian name, contrabbasso.

Other terms for the instrument among classical performers are string bass, bass viol, or simply bass. Jazz musicians often call it the acoustic bass to distinguish it from electric bass guitars. Especially when used in folk and bluegrass music, the instrument can also be referred to as an upright bass, standup bass, bass fiddle, bass violin, doghouse bass, dog-house, bull fiddle, hoss bass, or bunkhouse bass.

Design

The design of the double bass, in contrast to the instruments in the violin family, has never been fully standardized.

In general there are two major approaches to the design outline shape of the double bass, these being the violin form, and the viol or gamba form. A third less common design called the busetto shape (and very rarely the guitar or pear shape) can also be found. The back of the instrument can vary from being a round, carved back similar to that of the violin, or a flat and angled back similar to the viol family (with variations in between).

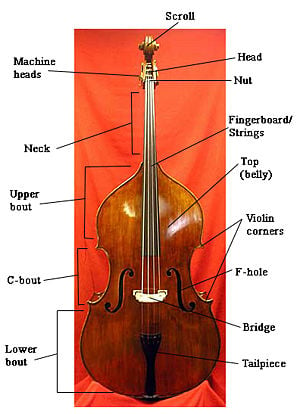

The double bass features many parts that are similar to members of the violin family including a bridge, f-holes, a tailpiece and a scroll.

Unlike the rest of the violin family, the double bass still can be considered partly derived from the viol family of instruments, in particular the violone, the bass member of the viol family.

The double bass also differs from members of the violin family in that the shoulders are (sometimes) sloped, the back is often angled (both to allow easier access to the instrument, particularly in the upper range) and machine heads are almost always used for tuning.

Lack of standardization in design means that one double bass can sound and look very different from another.

Tone

The sound and tone of the double bass is distinct from that of the fretted bass guitar and is similar to a cello. The differences in sound come from several sources which are discussed below.

The double bass's strings are stopped by the finger directly on the wooden fingerboard. This tends to make the string buzz against the fingerboard near the stopped position. The fretted bass guitar's strings are stopped with the aid of metal frets and buzzing does not generally occur.

Also, the double bass is an acoustic instrument with a hollow body that selectively amplifies the tone of the plucked or bowed strings. In contrast, bass guitars are often made with a solid wood body, and the sound is produced by electronic amplification of the vibration of the strings, which is "sensed" by magnetic pickups that also add to the characteristic tone.

Construction

The double bass is closest in construction to violins, but has some notable similarities to the violone (literally "large viol")—the largest and lowest member of the viola da gamba family. Unlike the violone, however, the fingerboard of the double bass is unfretted, and the double bass has fewer strings (the violone, like most viols, generally had six strings, although some specimens had five or four).

An important distinction between the double bass and other members of the violin family is the construction of the pegbox. While the violin, viola, and cello all use friction pegs for gross tuning adjustments, the double bass has machine heads. This development makes fine tuners unnecessary. At the base of the double bass is a metal spike called the endpin, which rests on the floor. This endpin is generally more robust than that of a cello, due to the greater mass of the instrument.

The soundpost and bass bar are components of the internal construction. The materials most often used are maple (back, neck, ribs), spruce (top), and ebony (fingerboard, tailpiece). The exception to this are the double basses sometimes used by blues, rockabilly, or bluegrass bassists, which have plywood-laminate tops and backs.

Today, one can find, mostly in Europe, some composite material basses. Used a lot in music schools, or as traveling basses for example, they are very resistant to humidity and heat.

All parts are glued together except the soundpost, bridge, nut and saddle, which are kept in place by string tension. The tuning machines are attached to the sides of the pegbox with wood screws. The key on the tuning machine turns a worm, driving a worm gear that winds the string.

Strings

Historically, strings were made of gut, but since the twentieth century, steel has largely replaced gut due to its better playability. Gut strings are nowadays mostly used by individual players who prefer their tone. Some bassists who perform in baroque ensembles use gut strings to get a lighter, "warmer" tone that is more appropriate for music composed in the 1600s and early 1700s. In addition, bassists in rockabilly, traditional blues bands, and bluegrass groups often use gut strings, because they produce a "thumpy," darker tone when they are played pizzicato (plucked), which better approximates the sound heard on 1940s and 1950s recordings. Rockabilly and bluegrass bassists also prefer gut because it is much easier to perform the "slapping" upright bass style (in which the strings are percussively slapped and clicked against the fingerboard) with gut strings than with steel strings. (For more information on slapping, see the sections below on Modern playing styles, Double bass in bluegrass music, Double bass in jazz, and Double bass in popular music).

Gut strings are more vulnerable to changes of humidity and temperature, and they break much more easily than steel strings. The change from gut to steel has also affected the instrument's playing technique over the last hundred years, because playing with steel strings allows the strings to be set up closer to the fingerboard, and, additionally, steel strings can be played in higher positions on the lower strings and still produce clear tone. The classic nineteenth century Franz Simandl method does not utilize the low E string in higher positions because with older gut strings set up high over the fingerboard, the tone was not clear in these higher positions. With modern steel strings, bassists can play with clear tone in higher positions on the low E and A strings, particularly when modern lighter-gauge, lower-tension steel strings (e.g., Corelli/Savarez strings) are used.

Tuning

The double bass is generally tuned in fourths, in contrast to the other members of the orchestral string family, which are all tuned in fifths. This avoids too long a finger stretch (known as an "extension"). Modern double basses are usually tuned (low to high) E-A-D-G. The lowest string is tuned to E (the same pitch as the lowest E on a modern piano, approx 41 Hz), nearly 3 octaves below middle C ); and the highest string is tuned to G, an octave and a fourth below middle C (approx 98Hz).

A variety of tunings and numbers of strings were used on a variety of confusingly-named instruments through the sixteenth to the early twentieth centuries, by which time the four-stringed tuning mentioned above became almost universal. Much of the classical repertoire has notes that fall below the range of a standard double bass. Some bassists use a fifth string tuned to B three octaves below middle C.

Professional bass players with four-string double basses sometimes have a low "C extension" which extends the lowest string down as far as low C, an octave below the lowest note on the cello (more rarely, this string may be tuned to a low B). The extension is an extra section of fingerboard mounted up over the head of the bass, which requires the player to reach back over the pegs to play, or use a mechanical lever system. Notes below low "E" appear regularly in double bass parts in the Baroque and Classical eras, when the double bass was typically doubling the cello part an octave below. Moreover, in the Romantic and the twentieth-century eras, composers such as Mahler and Prokofiev specifically requested notes below the low "E."

A small number of bass players choose to tune their strings in fifths, like a cello but an octave lower (C-G-D-A low to high). This tuning is mostly used by jazz players, as the major tenth can be played easily without a position shift, but is increasingly used by classical players, notably the Canadian bassist Joel Quarrington. Tuning in fifths can also make the instrument louder, because the strings have more common overtones, causing the strings to vibrate sympathetically[5].

In classical solo playing the double bass is usually tuned a whole tone higher (F#-B-E-A). This higher tuning is called "solo tuning," whereas the regular tuning is known as "orchestral tuning." String tension differs so much between solo and orchestral tuning that a different set of strings is often employed that has a lighter gauge. It is not uncommon for students that require solo tuning for a short period of time to tune up orchestra strings. Therefore the strings are always labelled for either solo or orchestral. Sometimes published solo music is also arranged especially for either solo or orchestral tuning.

Pitch range

The lowest note of a double bass is an E1 (on standard four-string basses) at 41.20 Hz or a B0 (when 5 strings are used) at 30.87 hertz, and the highest notes are almost down at the bridge.

In many double bass concertos, harmonic tones are used. The use of natural harmonics (a technique often used by Giovanni Bottesini) and sometimes even "false" harmonics, where the thumb stops the note and the octave or other harmonic is activated by lightly touching the string at the relative node point, extend the double bass' range considerably.

A solo player could cover some 5 or 6 octaves on his instrument using these harmonics, whereas in most orchestral music, the double bass parts seldom exceed 3 octaves.

Since the range of the double bass lies largely below the standard bass clef, it is notated an octave higher (hence sounding an octave lower than written). This transposition applies even when reading the tenor and treble clef, which are used to avoid excessive ledger lines when notating the instrument's upper range.

Playing posture

Double bassists have the option to either stand or sit while playing the instrument. When standing, the double bass' height is set (by adjusting the endpin) so that the player may easily place the right hand close to the bridge, either with the bow (arco) or plucking (pizzicato). While personal opinions vary, often the endpin is set by aligning the first finger in either first or half position with the player's eye level. While sitting, a stool (which is measured by the player's seam length) is used. Traditionally, standing has been preferred by soloists although many now choose to play sitting down.

When playing in the upper register of the instrument (above the G below middle C), the player shifts his hand out from behind the neck and flattens it out, using the side of his thumb as a finger. This technique is called thumb position and is also a technique used on the cello. While playing in thumb position, the use of the fourth finger is replaced by the third finger, as the fourth finger becomes too short to produce a reliable tone.

Bows

The double bass bow comes in two distinct forms. The "French" or "overhand" bow is similar in shape and implementation to the bow used on the other members of the orchestral string instrument family, while the "German" or "Butler" bow is typically broader and shorter, and is held with the right hand grasping the frog in a loose fist.

These two bows provide for different ways of moving the arm and distributing force on the strings. The French bow, because of the angle the hand holds the bow, is touted to be more maneuverable and provide the player with better control of the bow. The German bow is claimed to allow the player to apply more arm weight and thus more force on the strings. The differences between the two, however, are minute for a proficient player trained in using his/her respective bow. Both bows are used by modern players, and the choice between the two is a matter of personal preference.

German bow

The German bow Dragonetti is the older of the two designs. The bowing style was handed down from the time when the bows of all stringed instruments played had to be held in that fashion (middle three fingers between the stick and the hair) to maintain tension of the hair before screw threads were used.

The German bow has a taller frog, and is held with the palm angled upwards, as used for the upright members of the viol family. When held in correct manner, the thumb rests on top of the stick. The index and middle fingers are held together and support the bow at the point where the frog meets the stick. The little finger supports the frog from underneath, while the ring finger supports the index and middle fingers.

French bow

The French bow was not widely popular until its adoption by 19th-century virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini. This style is more similar to the traditional bows of the smaller string family instruments. It is held as if the hand is resting comfortably by the side of the performer with the palm facing toward the bass. The thumb rests at the edge of the U-curve in the frog while the other fingers drape on the other side of the bow. Various styles dictate the curve of the fingers and thumb, as do the style of piece- a more pronounced curve and lighter hold on the bow is used for virtuosic or more delicate pieces, while a flatter curve and sturdier grip on the bow provides more power for rich orchestral passages.

Rosin

In order to allow the hair to grip the string, string players use rosin on the hair of their bows. Double bass rosin is generally softer and stickier than violin rosin, to allow the hair to grab the strings better, but players use a wide variety of rosins that vary from quite hard (like violin rosin) to quite soft, depending on the weather, the humidity, and the skill and preference of the player.

Stick material

Pernambuco is regarded by many players as the best stick material, but due to its scarcity and expense, other materials are used in less expensive bows nowadays. Less expensive student bows may be constructed of solid fiberglass, or of less valuable varieties of brazilwood. Snakewood and carbon fiber are also used in bows of a variety of different qualities. The frog of the double bass bow is usually made out of ebony, although Snakewood is used by some luthiers. The wire wrapping is gold or silver in quality bows, and the hair is usually horsehair. Some of the lowest-quality student bows feature synthetic fiberglass "hair." Double bass bows vary in length, but average around 24" (70 cm).

Stringing

The double bass bow is strung with white or black horsehair, or a combination of black and white (known as "salt and pepper") as opposed to the customary white horsehair used on the bows of other string instruments. The slightly rougher black hair is believed by some to "grab" the heavier strings better; similarly, some bassists and luthiers believe that it is easier to produce a smoother sound with the white variety.

Practical problems

Loudness

Despite the size of the instrument, it is relatively quiet, primarily due to the fact that its range is so low. When the bass is being used as an ensemble instrument in orchestra, usually between four and eight bassists will play the part in unison. In jazz and blues settings, the bass is normally amplified. When writing solo passages for the bass, composers typically ensure that the orchestration is light, so it will not cover the bass.

Dexterity

Performing on the bass can be physically taxing because the strings of the bass are larger and thicker than those of a smaller stringed instrument. As well, since the bass is much larger than other stringed instruments, the space between notes on the fingerboard is larger. As a result, bass parts have relatively fewer fast passages, double stops, or large jumps in range. The increased use of playing techniques such as thumb position and modifications to the bass such as the use of lighter-gauge strings have reduced this problem to some degree.

Intonation

As with all unfretted string instruments, performers must learn to precisely place their fingers to obtain the correct pitch. Because the bass is larger than other string instruments, the positions for the fingers are much further apart. As a result, more shifting of position is required, which increases the likelihood of intonation errors. As well, for bassists with smaller hands, the large spaces between pitches on the bass fingerboard may present a challenge, especially in the lower range, where the spaces between notes are largest.

Size

Until recently, the large size of the bass meant that children were not able to start the bass until their hand size and height would allow them to play a 3/4-size instrument (the most commonly-available size). In the 1990s and 2000s, smaller half, quarter, eighth and even sixteenth-sized instruments became more widely available, which meant that children could start at a younger age. Some teachers have been known to use cellos strung with bass guitar strings for extremely young students.

Transportation issues

The double bass' large size, combined with the fragility of the wooden top and sides and the wood bodies' sensitivity to temperature and humidity changes can make it difficult to transport and store. Although double basses made of more damage-resistant carbon-fiber laminates or plywood laminate are available, these are less likely to be used by professional classical or jazz bassists.

Modern playing styles

In popular music genres, the instrument is usually played with amplification and almost exclusively played with a form of pizzicato where the sides of the fingers are used in preference to the tips of the fingers.

In traditional jazz, swing, rockabilly, and psychobilly music, it is sometimes played in the slap style. This is a vigorous version of pizzicato where the strings are "slapped" against the fingerboard between the main notes of the bass line, producing a snare drum-like percussive sound. The main notes are either played normally or by pulling the string away from the fingerboard and releasing it so that it bounces off the fingerboard, producing a distinctive percussive attack in addition to the expected pitch. Notable slap style bass players, whose use of the technique was often highly syncopated and virtuosic, sometimes interpolated two, three, four, or more slaps in between notes of the bass line.

"Slap style" had an important influence on electric bass guitar players who from about 1970 developed a technique called "slap and pop," where the thumb of the plucking hand is used to hit the string, making a slapping sound but still allowing the note to ring, and the index or middle finger of the plucking hand is used to pull the string back so it hits the fretboard, achieving the pop sound described above.

It is also used in the genre of psychobilly.

Classical repertoire

Orchestral excerpts

There are many examples of famous bass parts in classical repertoire. The scherzo and trio from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is a very famous orchestral excerpt for the double bass. The recitative at the beginning of the fourth movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony is also an extremely famous orchestral excerpt. Both of these examples are frequently requested in orchestra auditions. Another prominent example would be the opening of the prelude to act I of Wagner's Die Walküre.

Orchestral solos

Some composers such as Richard Strauss assigned the double bass with daring parts and his symphonic poems and operas stretch the double bass to its limits. Some solo works have been written such as Mozart aria "Per questa bella mano" (By this beautiful hand), Ludwig von Köchel, for bass voice, double bass, and orchestra, featuring the double bass as an obbligato. "The Elephant" from Camille Saint-Saëns' The Carnival of the Animals is also a well known example of a double bass solo. The third movement of Gustav Mahler's 1st symphony features a solo for the double bass which quotes the children's song "Frere Jacques," transposed into a minor key. Sergei Prokofiev's "Lieutenant Kijé Suite" features an important double bass solo in the "Romance" movement. Later pieces with solo parts for the bass include a duo for cello and double bass by Gioacchino Rossini. Popular with bassists is Niccolò Paganini's Fantasy on a Theme by Rossini, a twentieth-century transcription of the violin original. Benjamin Britten's The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra contains a prominent double bass solo.

Quintets

The Trout Quintet by Franz Schubert added the double bass to the traditional piano quartet, creating an ensemble consisting of four members of the bowed string family plus piano. Antonín Dvořák wrote a much less well known quintet with double bass. The Prokofiev Quintet is a challenging piece, which features the violin, viola, double bass, clarinet and oboe. Other pieces written for string quintets with a double bass added onto a string quartet exist by Darius Milhaud, Murray Adaskin, Giovanni Bottesini, Domenico Dragonetti and Edgar Meyer.

Concertos

Domenico Dragonetti influenced Beethoven to write more difficult bass parts which still remain as some of the most challenging bass parts written in the orchestral literature and he wrote a large number of works for the double bass which include ten concertos and various pieces for double bass and piano.

Joseph Haydn wrote a concerto for double bass, Hob. VIIc 1 (now lost), for Johann Georg Schwenda, at Esteháza. Haydn wrote solo passages in the trios of the minuets in his symphonies numbers 6, 7 and 8 (Le Matin, Le Midi and Le Soir). Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf wrote two concertos for double bass and a Sinfonia Concertante for viola, double bass, and orchestra. Johann Baptist Vanhal also composed a concerto for the double bass which remains standard repertoire today.

In addition to being a virtuoso player, Johannes Matthias Sperger was a very prolific composer and composed a large number of works for the double bass. Among his compositions include 18 double bass concertos, around 30 double bass sonatas, and string symphonies. Giovanni Bottesini, a nineteenth century virtuoso on the instrument, wrote a number of concert pieces for the instrument, including two concertos for the double bass and various chamber works for double bass and piano.

In 1905, Serge Koussevitzky (better known as a conductor) wrote a concerto for the instrument. Reinhold Glière, composed four short pieces for double bass and piano (Intermezzo, Op. 9.1, Tarantella, Op. 9.2, Preladium, Op. 32.1, and Scherzo, Op. 32.2). Eduard Tubin wrote a concerto for double bass in 1948. Other works for double bass and orchestra include Gunther Schuller's Concerto (1962), Hans Werner Henze's Concerto (1966), Nino Rota's Diveritmento for Double Bass and Orchestra (1973), Jean Françaix's Concerto (1975), Einojuhani Rautavaara's Angel Of Dusk (1980), Gian Carlo Menotti's Concerto (1983), Christopher Rouse's Concerto (1985), and John Harbison's Concerto for Bass Viol (2006). Other pieces for solo double bass include Luciano Berio's Psy (1989), for solo bass; Composition II (1973) by Galina Ustvolskaya, for eight double basses, drum and piano; and a sonata for double bass and piano by Paul Hindemith (who also wrote a number of other pieces for unusual solo instruments).

New works

Over the last 30 years or so players with solo careers such as Bertram Turetzky, Gary Karr, and James VanDemark have commissioned a large number of new works. Player and composer Edgar Meyer has written two concertos for solo double bass and a double concerto for double bass and cello for the instrument and had made arrangements of Bach's unaccompanied cello suites. Meyer also includes the double bass in the majority of his chamber music compositions.

Player and teacher Rodney Slatford, via his company Yorke Edition, has published both old and new music for the double bass. Frank Proto, former bassist of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, has published a large number of his own compositions as well as new editions of classic double bass repertoire via his company Liben Music. George Vance, noted teacher and author of "Progressive Repertoire for Double Bass," provides numerous publications from his company Slava Publishing. Norman Ludwin, bassist and composer, has published with his company Ludwin Music over three hundred pieces for the bass, including many original works as well as transcriptions.

Other composers that have written for solo double bass include Christian Wolff, Iannis Xenakis, Salvatore Sciarrino, Hans Werner Henze, Emil Tabakov, Vincent Persichetti, Miloslav Gajdoš, Henrik Hellstenius, Hans Fryba, Ase Hedstrom, Tom Johnson, Arne Nordheim, Luis Jorge Gonzalez, Oliver Knussen, Giacinto Scelsi, Bezhad Ranjbaran, and Asmund Feidje.

Use in jazz

Beginning around 1890, the early New Orleans jazz ensemble (which played a mixture of marches, ragtime, and dixieland music) was initially a marching band with sousaphone (or occasionally bass saxophone) supplying the bass line. As the music moved into bars and brothels, the double bass gradually replaced these wind instruments. Many early bassists doubled on both the "brass bass" and "string bass," as the instruments were then often referred to. Bassists played "walking" basslines, scale-based lines which outlined the harmony.

Because an unamplified double bass is generally the quietest instrument in a jazz band, many players of the 1920s and 1930s used the slap style, slapping and pulling the strings so that they make a rhythmic "slap" sound against the fingerboard. The slap style cuts through the sound of a band better than simply plucking the strings, and allowed the bass to be more easily heard on early sound recordings, as the recording equipment of that time did not favor low frequencies[6]. For more about the slap style, see "Modern playing styles," above.

Double bass players have contributed to the evolution of jazz. Examples include swing era players such as Jimmy Blanton, who played with Duke Ellington, and Oscar Pettiford, who pioneered the instrument's use in bebop. Ray Brown, known for his virtuosic bowing technique, has been called "the Fritz Kreisler of jazz double bass playing." The "cool" style of jazz was influenced by players such as Scott LaFaro and Percy Heath, whose solos were melodic. Paul Chambers (who worked with Miles Davis on the famous Kind of Blue album) achieved renown for being one of the first jazz bassists to play solos in arco (bowed) style.

Free jazz was influenced by the composer/bassist Charles Mingus (who also contributed to hard bop) and Charlie Haden, best known for his work with Ornette Coleman. Beginning in the 1970s, some jazz bandleaders such as saxophonist Sonny Rollins and fusion bassist Jaco Pastorius began to substitute the electric bass guitar for the double bass. Apart from the jazz styles of jazz fusion and Latin-influenced jazz, the double bass is still widely used in jazz.

Use in bluegrass

The string bass is the most commonly-used bass instrument in bluegrass music and is almost always plucked, though some modern bluegrass bassists have also used a bow. The Englehardt or Kay brands of basses have long been popular choices for bluegrass bassists. While most bluegrass bassists use the 3/4 size bass, the full and 5/8 size basses are less frequently used.

The bluegrass bass is responsible for keeping time in the polyrhythmic conditions of the bluegrass tune. Most important is the steady beat, whether fast, slow, in 4/4 time, 2/4 or 3/4 time.

Early pre-bluegrass music was often accompanied by the cello, which was bowed as often as plucked. Some contemporary bluegrass bands favor the electric bass, but it has a different musical quality than the plucked upright bass. The upright bass gives energy and drive to the music with its percussive, woody tone. Slapping is a widely-used bluegrass playing technique.

Common rhythms in bluegrass bass playing involve (with some exceptions) plucking on beats 1 and 3 in 4/4 time; beats 1 and 2 in 2/4 time, and beats 1 and 3 and in 3/4 time (waltz time). Bluegrass bass lines are usually extremely simple, typically staying on the root and fifth of each chord throughout much of a song. There are two main exceptions to this "rule." Bluegrass bassists often do a diatonic "walkup" or "walkdown" in which they play every beat of a bar for one or two bars, typically when there is a prominent chord change. In addition, if a bass player is given a solo, they may play a walking bass line.

The first bluegrass bassist to rise to prominence was Howard Watts (also known as Cedric Rainwater), who played with Bill Monroe's Blue Grass Boys beginning in 1944[7]. One of the most famous bluegrass bassists is Edgar Meyer, who has now branched out into newgrass, classical, and other genres.

Use in popular music

In the 1940s, a new style of dance music called rhythm and blues developed, incorporating elements of the earlier styles of blues and swing. Louis Jordan, the first innovator of this style, featured a double bass in his group, the Tympany Five[8]. The double bass remained an integral part of pop lineups throughout the 1950s, as the new genre of rock and roll was built largely upon the model of rhythm and blues, with strong elements also derived from jazz, country, and bluegrass. However, double bass players using their instruments in these contexts faced inherent problems. They were forced to compete with louder horn instruments (and later amplified electric guitars), making bass parts difficult to hear. The double bass is difficult to amplify in loud concert venue settings, because it can be prone to feedback "howls." The double bass is large and awkward to transport, which also created transportation problems for touring bands.

In 1951, Leo Fender independently released his Precision Bass, the first commercially successful electric bass guitar[9]. The electric bass was easily amplified with its built-in pickups, easily portable (less than a foot longer than an electric guitar), and easier to play in tune, thanks to the metal frets. In the 1960s and 1970s bands were playing at louder volumes and performing in larger venues. The electric bass was able to provide the huge, highly-amplified stadium-filling bass tone that the pop and rock music of this era demanded, and the double bass receded from the limelight of the popular music scene.

The upright bass began making a modest comeback in popular music in the mid-1980s, in part due to a renewed interest in earlier forms of rock and country music. In the 1990s, improvements in pickups and amplifier designs for electro-acoustic horizontal and upright basses made it easier for bassists to get a good, clear amplified tone from an acoustic instrument. Some popular bands decided to anchor their sound with an upright bass instead of an electric bass. A trend for "unplugged" performances further helped to enhance the public's interest in the upright bass and acoustic bass guitars.

The double bass is also favored over the electric bass guitar in many rockabilly and psychobilly bands. In such bands the bassist often plays with great showmanship, using slapping technique, sometimes spinning the bass around or even physically climbing onto the instrument while performing; this style was pioneered c. 1953 by Marshall Lytle, the bassist for Bill Haley & His Comets[10], and modern performers of such stunts include Scott Owen from The Living End.

Double bassists

Notable classical players of historical importance

- Domenico Dragonetti (1763-1846) Virtuoso, composer, conductor

- Giovanni Bottesini (1821-1889) Virtuoso, composer, conductor

- Franz Simandl (1840-1912) Virtuoso, composer

- Edouard Nanny (1872-1943) Virtuoso, composer

- Serge Koussevitzky (1874-1951) Conductor, virtuoso, composer

Notes

- ↑ Andrew Hugill with the Philharmonia Orchestra, The Orchestra: A User's Manual. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Alfred Planyavsky, Chamber Music in the Vienna Double Bass Archive.earlybass.com. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Jacob Head,The Double Bass.contrabas.com.Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Paul Brun.A New History of the Double Bass. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Dennis Masuzzo,Taking the Fifth: How Tuning in Fifths Changed My Experience Playing the Double Bass. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Historic Jazz Fotos.peterunbehauen. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Stewart EvansHoward "Cedric Rainwater" Watts. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Dallas Bartley - Small town Boy: Playing in the bands, Special Collections and Archives Department, Southwest Missouri State University. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Monica M. Smith,The Electric Guitar: How We Got From Andrés Segovia To Kurt Cobain.Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Rod Glaze.Marshall Lytle: Granddaddy of the Doghouse. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Farish, Margaret K. String music in print. NY: R.R. Bowker Co., 1965. OCLC 494785

- Lane, Zachary; Van Beekom, Karel; Ruggiero, Greg, et al. Graduate recital, double bass. MI: Western Michigan University, School of Music, 2007. OCLC 144496773

- Meyer, Edgar, bassist. Edgar Meyer. NY: Sony Classical, 2006. OCLC 123094956

- Oppelt, Robert J.; Oppelt, Nicolette; Adkins, Elisabeth, et al. The double bass. Newtown, CT: MSR Classics, 2007. OCLC 123998691

- Park, Hyuk; Jung, Seung Hae. Hyuk Park, double bass. 2007. OCLC 141189078

- Planyavsky, Alfred. The baroque double bass violone. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1998. ISBN 0810834480

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.