Cello

| ||||||||

|

The violoncello, almost always abbreviated to cello, or 'cello (the c is pronounced [tʃ] as the ch in "cheese"), is a bowed stringed instrument, the lowest-sounding member of the violin family. A person who plays a cello is called a cellist.

The cello is popular in many capacities: as a solo instrument, in chamber music, and also be used as a foundation of the modern orchestral sound.

Description

The name cello (plural: celli, cello) is an abbreviation of the Italian violoncello, which means "little violone." The violone is an obsolete instrument, a large viol, similar to a modern double bass.

The cello is most closely associated with European classical music. It is part of the standard orchestra and is the bass voice of the string quartet, as well as being part of many other chamber groups. A large number of concertos and sonatas have been written for it. It is less common in popular music, but is sometimes featured in pop and rock recordings. The cello has also been modified for Indian classical music by Saskia Rao-de Haas.

Among the most famous Baroque works for the cello are J. S. Bach's Unaccompanied Suites for Cello, commonly known as the Bach Cello Suites. An example of a Classical era piece is Haydn's Cello Concerto #1 in C major. Standard Romantic era repertoire includes the Cello Concerto in B minor by Antonín Dvořák, Elgar's Cello Concerto in E minor, and the two sonatas by Brahms. Modern compositions from the early twentieth century include unaccompanied cello sonatas by Paul Hindemith (opus 25) and Zoltán Kodály (opus 8). Recordings within the Avant Garde (cutting edge) genre have revitalized the instrument's perceived versatility. One example is Night of the Four Moons by George Crumb.

Construction

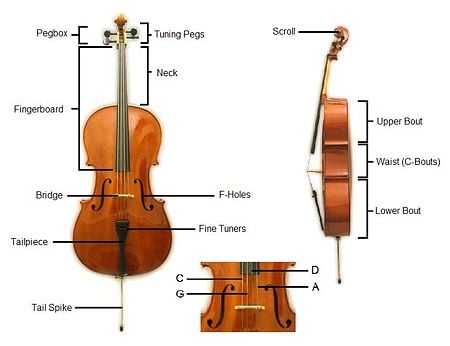

The cello is larger than the violin or the viola but smaller than the double bass. Like the other members of the violin family, the cello has four strings. Its strings are normally tuned to the pitches (from high to low) A, D, G, and C (A3, D3, G2, and C2 in scientific pitch notation). The strings are tunes one octave lower than the viola, and one octave plus one fifth lower than the violin (see Tuning and range). The cello is played in an upright position, held by the knees of a seated musician, resting on a spike called the endpin. The player draws the bow horizontally across the strings, making them vibrate. The cello is a complex instrument consisting of many different parts. Although the majority of it is composed of wood, some parts can be made of steel or other metals and/or composite material. Modern strings have a steel, gut, nylon or other synthetic core, covered with various kinds of metal winding.

Body

The main frame of the cello is typically made from wood, although some modern celli are constructed from carbon fibre, given the strength of the material and its resistance to humidity and temperature fluctuations. Carbon fiber cellos are particularly suitable for outdoor playing.

A traditional cello normally has a spruce top, with maple for the back, sides, and neck. Other woods, such as poplar or willow, are sometimes used for the back and sides. Less expensive celli frequently have a top and back made of a laminate.

The top and back are traditionally hand-carved, though less expensive celli are often machine-produced. The sides, or ribs, are made by heating the wood and bending it around forms. The cello body has a wide top bout, narrow middle formed by two C-bouts, and wide bottom bout, with the bridge and sound holes just below the middle.

Neck, pegbox, and scroll

Above the main body is the carved neck, which leads to a pegbox and the scroll. The neck, pegbox, and scroll are normally carved out of a single piece of wood. Attached to the neck and extending over the body of the instrument is the fingerboard. The nut is a raised piece of wood, where the fingerboard meets the pegbox, which the strings rest on. The pegbox houses four tuning pegs, one for each string. The pegs are used to tune the cello by either tightening or loosening the string. The scroll is a traditional part of the cello and all other members of the violin family. Ebony is usually used for the tuning pegs, fingerboard, and nut, but other hard woods, such as boxwood or rosewood, can be used.

Tailpiece and endpin

The tailpiece and endpin are found in the lower part of the cello. The tailpiece is traditionally made of ebony or another hard wood, but can also be made of plastic or steel. It attaches the strings to the lower end of the cello, and can have one or more fine tuners. The endpin, made of metal or carbon fiber, supports the cello in playing position. Modern endpins are retractable and adjustable; older ones were made of wood and could be removed when not in use. The tip of the endpin is sometimes capped with a rubber tip that prevents the cello from slipping on the floor.

Bridge and f-holes

The bridge elevates the strings above the cello and transfers their vibrations to the top of the instrument and the soundpost inside (see below). The bridge is not glued, but rather held in place by the tension of the strings. The f-holes (named for their shape) are located on either side of the bridge, and allow air to move in and out of the instrument to produce sound. Additionally, the f-holes act as access points to the interior of the cello for repairs or maintenance. Sometimes a small hose, containing a water-soaked sponge, is inserted through the f-holes, and serves as a humidifier.

Internal features

Internally, the cello has two important features: a bass bar, which is glued to the underside of the top of the instrument, and a round wooden sound post, which is wedged between the top and bottom plates. The bass bar, found under the bass foot of the bridge, serves to support the cello's top and distribute the vibrations. The sound post, found under the treble side of the bridge, connects the back and front of the cello. Like the bridge, the sound post is not glued, but is kept in place by the tensions of the bridge and strings. Together, the bass bar and sound post are responsible for transferring the strings' vibrations to the body of the instrument, which in turn transfers them to the air mass inside the instrument, thus producing sound.

Glue

Celli are constructed and repaired using hide glue, which is strong but reversible, allowing for disassembly when needed. Tops may be glued on with diluted glue, since some repairs call for the removal of the top. Theoretically, hide glue is weaker than the body's wood, so as the top or back shrinks side-to-side, the glue holding it will let go, avoiding a crack in the plate. However, in reality this does not always happen.

Bow

Traditionally, bow sticks are made from Pernambuco (high quality) or brazilwood (lower quality). Both woods come from the same species of tree (Caesalpina echinata), but Pernambuco is the heartwood of the tree and is much darker (Brazilwood is stained/painted dark to compensate). Pernambuco is a heavy, resinous wood with great elasticity and high sound velocity which makes it an ideal wood for instrument bows.

Bow sticks can also be made from carbon-fiber, which is stronger than wood. Inexpensive, low-quality student bows are often made from fiberglass.

The bow hair is horsehair, though synthetic hair in different colors is also available. The hair is coated with rosin periodically to make it grip the strings and cause them to vibrate. Bows need to be re-haired periodically, especially if the hairs break frequently or lose their gripping quality. The hair is kept under tension while playing by a screw which pulls the frog (the part of the bow one holds) back. Leaving the bow tightened for long periods of time can damage it by warping the stick. The dimensions of the cello bow are 73cm long, 3cm high (from the frog to the stick) and 1.5 cm wide.

Development

The cello developed from the bass violin, first used by Monteverdi, which was a three-string consort instrument. The invention of wire-wound strings (fine wire around a thin gut core), around 1660 in Bologna, allowed for a finer bass sound than was possible with purely gut strings on such a short body. Bolognese makers exploited this new technology to create the cello, a somewhat smaller instrument suitable for solo repertoire due to both the timbre of the instrument and the fact that the smaller size made it easier to play virtuosic passages. This instrument had disadvantages as well, however. The cello's light sound was not as suitable for church and ensemble playing, so it had to be doubled by basses or violones.

Around 1700 Italian players popularized the cello in northern Europe, although the bass violin continued to be used for another two decades in France and England. The sizes, names, and tunings of the cello varied widely by geography and time. The size was not standardized until around 1750.

Despite superficial similarities, the cello is not in fact related to the viola da gamba. The cello is actually part of the viola da braccio family, meaning viol of the arm, which includes, among others, the violin and viola. There are actually paintings of people playing the cello on the shoulder, like a giant violin. It was only somewhat later that the cello began to be played while being supported by the calves, and even later, by an endpin (spike).

Baroque era celli differed from the modern instrument in several ways. The neck has a different form and angle which matches the baroque bass-bar and stringing. Modern celli have an endpin at the bottom to support the instrument (and transmit some of the sound through the floor), while Baroque celli are held only by the calves of the player. Modern bows curve in and are held at the frog; Baroque bows curve out and are held closer to the bow's point of balance. Modern strings normally have a metal core, although some use a synthetic core; Baroque strings are made of gut, with the G and C strings wire-wound. Modern celli often have fine-tuners connecting the strings to the tailpiece, which make it much easier to tune the instrument. Overall, the modern instrument has much higher string tension than the Baroque cello, resulting in a louder, more projecting tone, with fewer overtones.

No educational works specifically devoted to the cello existed before the 18th century, and those that do exist contain little value to the performer beyond simple accounts of instrumental technique. The earliest cello manual is Michel Corrette's Méthode, thèorique et pratique pour apprendre en peu de temps le violoncelle dans sa perfection (Paris, 1741).

Sound

The cello produces a deep, rich, and vibrant sound. The cello reaches the lowest pitch in the traditional string quartet and is capable of covering nearly the entire range of pitches produced by the human voice. In the upper register, many celli may be said to have a "tenor-like" timbre. The lowest possible pitch is C2, two octaves below middle C. The highest pitch (without considering harmonics) on the fingerboard is somewhere around F#6, played on the A string, but Zoltán Kodaly's solo sonata requires a spectacular B6 to be played in the concluding measures.

Playing technique

Body position

The cello is played sitting, held between the knees of the player, the upper bout resting against the upper chest. The neck of the cello is above the player's left shoulder. In early times, female cellists sometimes played side-saddle, since it was considered improper for a lady to part her knees in public.

Left hand technique

The left hand fingers determine the pitch of the note. The thumb is positioned on the back of the neck (in "neck" positions), or on top of the sting, alongside the fingers (in "thumb" position). The fingers are normally held curved with each knuckle bent, unless certain intervals require flat fingers (as in fifths). In fast playing, the fingers contact the strings at the tip, almost at the nail. In slower, or more expressive playing, the flat of the fingerpad is used, allowing a richer tone and fuller vibrato. If the string is depressed closer to the bridge, the resulting pitch will be higher sounding because the string has been shortened. If it is depressed further up the string, closer to the scroll of the instrument, the pitch will be lower.

Additional left hand techniques

Vibrato

Vibrato consists of oscillating the playing left hand finger around the center of the desired pitch. As a result, the pitch of the note will waver slightly, much as a singer's voice on a sustained note. A well developed vibrato technique is a key expressive device and an essential element of an accomplished string player. In some styles of music, such as that of the Romantic period, vibrato is used on almost every note. However, in other styles, such as Baroque repertoire, vibrato is used only rarely, as an ornament. Typically, the lower the pitch of the note played, the wider the vibrato.

Glissando

Glissando ("sliding," in Italian) is an effect played by sliding the finger up or down the fingerboard without releasing the string. This causes the pitch to rise and fall smoothly, without separate, discernible steps.

Harmonics

Harmonics are produced by lightly touching, but not fully depressing, the string with the finger at certain places, and then bowing (rarely even plucking) the string. For example, the halfway point of the string will produce a harmonic that is one octave above the unfingered (open) string (in effect doubling the frequency of the open string). There are also artificial harmonics, in which the player depresses the string with one finger while touching the same string lightly with another finger (at certain intervals, mostly of a perfect fourth higher). This technique produces a distinctive sound effect, resembling the flute. Artificial harmonics are performed routinely with the thumb (pressed fully) and the third finger (lightly touching the same string, a fourth higher).

Right hand technique

In cello playing, the bow is much like the breath of a wind instrument player. Arguably, it is the major determinant in the expressiveness of the playing. The right hand holds the bow and controls the duration and character of the notes. The bow is drawn across the strings roughly halfway between the end of the fingerboard and the bridge, in a direction perpendicular to the strings. The bow is held with all five fingers of the right hand, the thumb opposite the fingers and closer to the cellist's body. The shape of the hand should resemble that of its relaxed state, with all fingers curved, including the thumb. The transmission of weight from the arm to the bow happens through the pronation (inward rotation) of the underarm, thus pushing the index finger and to a lesser degree the middle finger onto the bow. The necessary counterforce is provided by the thumb. The little finger controls the angle to the string and the balance of the bow when it is lifted off the string (see spiccato). The shoulder remains relaxed, as well as the arm. On a "down-bow," the bow is drawn to the right of the player, moving the hand by first using the upper arm, then the forearm, then the wrist (turning slightly inward) in order to maintain a straight stroke. On an "up-bow," the bow is drawn to the left, moving first the forearm, then the upper arm, then the wrist (pushing slightly upward). The bow is mostly use perpendicular to the string being played. In order to perform string changes the whole arm is either lowered or lifted, with as little wrist movement as possible in order to maintain the angle to the string. However, a certain flexibility of the wrist is necessary when changing the bow direction from up-bow to down-bow and vice versa. For very fast bow movements, the wrist is used to accomplish the horizontal movement of bow. For longer strokes, the arm is used as well as the wrist.

Tone production and volume of sound depend on a combination of several factors. The three most important ones are: bow speed, weight applied to the string, and point of contact of the bow hair with the string. A good player will be capable of a very even tone, and will counter the natural tendency to play with the most force with the part of the bow nearest to the frog or heel, and the least force near the tip. The closer to the bridge the string is bowed, the more projecting and brighter the tone, with the extreme (sul ponticello) producing a metallic, shimmery sound. If bowing closer to the fingerboard (sul tasto), the sound produced will be softer, more mellow, and less defined.

Additional right hand techniques

Double stops

Double stops involve the playing of two notes at the same time. Two strings are fingered simultaneously, and the bow is drawn so as to sound them both at once. Triple and quadruple stops may also be played (in a "broken" fashion), but are difficult to sustain because of the change in slope of the bridge. One contemporary cellist, Frances-Marie Uitti, has come up with a two-bow system with one bow above the strings and one under, allowing for sustained triple and quadruple stops.

Pizzicato

In pizzicato playing, the string is plucked with the right hand fingers, or very rarely those of the left hand, and the bow is simply held away from the strings by the rest of the hand or even set down. A single string can be played pizzicato, or double, triple, or quadruple stops can be played. Occasionally, a player must bow one string with the right hand and simultaneously pluck another with the left. This is marked by a "+" above the note. Strumming of chords is also possible, in guitar fashion.

Col legno

Col legno is the technique in which the player taps the wooden stick of the bow on the strings, which gives a percussive sound that is quite often used in contemporary music. A famous example is the opening of 'Mars' from Gustav Holst's 'Planets' suite, where the entire string section of the orchestra plays Col legno.

Spiccato

In spiccato, or "bouncy bow" playing, the strings are not "drawn" by the bow but struck by it, while still retaining some horizontal motion, to generate a more percussive, crisp sound. It may be performed by using the wrist to "dip" the bow into the strings. Spiccato is usually associated with lively playing. On a violin, spiccato bowing comes off the string, but on a cello, the wood of the bow may rise briskly up without the hair actually leaving the string.

Staccato

In staccato, the player moves the bow a very short distance, and applies greater pressure to create a forced sound.

Legato

Legato is a technique where the notes are drawn out and connected for a smooth sounding piece.

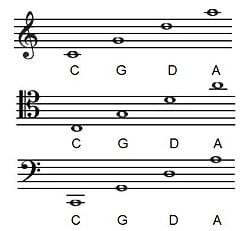

Tuning and range

The cello has four strings referred to by their standard tuning, which is in perfect fifth intervals: the A-string (highest sounding), D-string, G-string, and C-string (lowest sounding). The A-string is tuned to the pitch A3 (below middle C), the D-string a fifth lower at D3, the G-string a fifth below that at G2, and the C-string tuned to C2 (two octaves lower than middle C). Some pieces, notably the 5th of Bach's 6 Suites for Unaccompanied Cello, require an altered tuning of the strings, known as scordatura; another well-known example is Zoltán Kodály's Solo Cello Sonata. Many believe that the 6th of Bach's 6 Suites for Unaccompanied Cello was actually written for a five string "violoncello piccolo," a smaller cello with a high E-string above the A-string, that is no longer commonly used. Five-string acoustic violins, violas and basses are difficult to find. However, many electric string instruments can have five or even six strings.

While the lower range of the cello is limited by the tuning of the lowest string (typically C2, two octaves below middle C), the upper range of the cello varies according to the skill of the player, and length of the fingerboard. A general guideline when writing for professional cellists sets the upper limit at C6 (two octaves above middle C), although even higher pitches are possible, up to one extra octave. Because of the extended range of the instrument, music for the cello frequently alternates between the bass clef, tenor clef, and treble clef. Some romantic composers (notably Dvořák) also wrote notes in treble clef, but intended them to be played an octave lower than written; this technique was more common during the eighteenth century.

Sizes

Standard-sized celli are referred to as "full-size." However, celli come in smaller (fractional) sizes, from "seven-eighths" and "three-quarter" down to "one-sixteenth" sized celli (e.g. 7/8, 3/4, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/10, 1/16). The smaller-sized celli are identical to standard cellos in construction, range, and usage, but are simply 'scaled-down' for the benefit of children and shorter adults. A "half-size" cello is not actually half the size of a "full-size," but only slightly smaller. Many smaller cellists prefer to play a "seven-eighths" cello as the hand stretches in the lower positions are less demanding. Although rare, celli in sizes larger than four-fourths do exist. Cellists with unusually large hands may play a slightly larger than full-sized cello. Cellos made before approximately 1700 tended to be considerably larger than those made after that date, and than those made and commonly played today. Around 1680, string-making technology made lower pitches on shorter strings possible. The cellos of Stradivari, for example, can be clearly divided into two models, with the style made before 1702 characterized by larger instruments (of which only three examples are extant in their original size and configuration), and the style made during and after 1702, when Stradivari, presumably in response to the "new" type of strings, began making cellos of a smaller size. This later model is the one most commonly used by modern luthiers.

Accessories

There are many accessories to the cello, (some more essential than others).

- Cases are used to protect the cello and bow when traveling, and for safe storage.

- Rosin, made from conifer resin, is applied to the bow hairs to increase the effectiveness of the friction and allow proper sound production.

- Rockstops "Black Holes" or endpin straps keep the cello from sliding if the endpin does not have a rubber piece on the end (used on wood floors).

- Wolf tone eliminators are sometimes placed on cello strings between the tailpiece and the bridge in order to eliminate acoustic anomalies known as wolf tones or "wolfs."

- Mutes are used to change the sound of the cello by reducing overtones. Practice mutes (made of metal) reduce significantly the instrument's volume (they are also referred to as "hotel mutes").

- Metronomes provide a steady tempo by sounding out a certain number of beats per minute. Many models can also produce a tuning pitch of A4 (440 Hz), among others.

- Humidifiers are used to control and stabilize the humidity around and inside the cello.

- Tuners are used to tune the instrument.

Current use

Orchestral

Celli are part of the standard symphony orchestra. Usually, the orchestra includes eight to twelve cellists. The cello section, in standard orchestral seating, is located on stage left (the audience's right) in the front, opposite the first violin section. However, some orchestras and conductors prefer switching the positioning of the viola and cello sections. The principal, or "first chair" cellist is the section leader, determining bowings for the section in conjunction with other string principals, and playing solos. Principal players always sit closest to the audience.

The celli are a critical part of orchestral music; all symphonic works involve the cello section, and many pieces require cello soli or solos. Much of the time, celli provide part of the harmony for the orchestra. On many occasions, the cello section will play the melody for a brief period of time, before returning to the harmony. There are also cello concertos, which are orchestral pieces in which a featured, solo cellist is accompanied by an entire orchestra.

Solo

There are numerous cello concertos, notably by Vivaldi, C.P.E. Bach, Haydn, Boccherini, Schumann, Saint-Saëns, Dvorák and Elgar where the cello is accompanied by an orchestra. Beethoven's Triple Concerto for Cello, Violin and Piano and Brahms' Double Concerto for Cello and Violin are also part of the concertante repertoire although in both cases the cello shares solo duties with at least one other instrument. Moreover, several composers wrote large-scale pieces for cello and orchestra, which are concertos in all but name. The most important are Richard Strauss' tone poem Don Quixote, Tchaikovsky's Variations on a Rococo Theme, Ernest Bloch's Schelomo and Max Bruch's Kol Nidrei.

In the twentieth century, the cello repertoire experienced an unprecedented growth. This was largely due to the influence of virtuoso cellist Mstislav Rostropovich who inspired, commissioned and/or premiered dozens of new works. Among these, Prokofiev's Symphonia Concertante, Britten's Cello Symphony and the concertos of Shostakovich, Lutoslawski and Dutilleux have already become part of the standard repertoire. In addition, Hindemith, Barber, Walton and Ligeti also wrote major concertos for other cellists (notably Gregor Piatigorsky and Siegfried Palm).

There are also many sonatas for cello and piano. Those written by Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Brahms, Grieg, Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Britten are the most famous.

Finally, there are also several unaccompanied pieces for cello, most notably J.S. Bach's Unaccompanied Suites for Cello (arguably the most important cello pieces), Zoltán Kodály's Sonata for Solo Cello and Britten's Unaccompanied Suites for Cello. Most recently the solo cello music of Aaron Minsky has become widely accepted and performed, especially his "Ten American Cello Etudes," which combines the traditional European "cello etude" with modern "American" musical styles such as rock, blues and jazz.

Quartet/Ensembles

The cello is a member of the traditional string quartet. In addition, celli are also usually part of string quintets, sextet or trios. There have been several pieces written for a cello ensemble of up to twenty or more cellists. This type of ensemble is often called a 'cello choir'. The Twelve Cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (or "the Twelve" as they are commonly referred to) are a prime example of a cello choir. They play and record pieces written especially for twelve celli including adaptations of well-known popular songs.

Popular music

Though the cello is less common in popular music than in "classical" music, it is sometimes featured in pop and rock recordings. The cello is rarely part of a group's standard lineup (though like its cousin the violin it is becoming more common in mainstream pop).

The Beatles pioneered the use of a cello in popular music, in songs such as "Eleanor Rigby" and "Strawberry Fields Forever." In the 1970s, the Electric Light Orchestra enjoyed great commercial success taking inspiration from so-called "Beatlesque" arrangements, adding the cello (and violin) to the standard rock combo line-up.

Established non-traditional cello groups include Apocalyptica, a group of Finnish cellists best known for their versions of Metallica songs, Rasputina, a group of two female cellists committed to an intricate cello style intermingled with Gothic music, Von Cello, a cello fronted rock power trio, and Break of Reality. These groups are examples of a style that has become known as cello rock. The crossover string quartet Bond also includes a cellist. Silenzium and Vivacello are Russian (Novosibirsk) groups playing rock and metal and having more and more popularity.

More recent bands using the cello are Aerosmith, Nirvana, Oasis, and Cursive. So-called "chamber pop" artists like Kronos Quartet and Margot and the Nuclear So and So's have also recently made cello common in modern alternative rock. Heavy metal band System of a Down has also made use of the cello's rich sound. The Seattle emo/rock group Nine Months Later uses a cello in their regular lineup.

The cello can also used in fiddling, bluegrass, and folk music.

Makers / Luthiers

A violin maker or luthier is someone who builds or repairs stringed instruments, ranging from guitars to violins. Some well known cello luthiers include:

- Nicolo Amati

- Nicolò Gagliano

- Matteo Gofriller

- Giovanni Battista Guadagnini

- Giuseppe Guarneri

- Domenico Montagnana

- Stefano Scarampella

- Antonio Stradivari

- David Tecchler

- Carlo Giuseppe Testore

- Jean Baptiste Vuillaume

Reference

- Bonta, Stephen, L. Macy, (ed.), "Violoncello," Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. London: MacMillan Publisher Ltd., 1980. ISBN 1561591742

- Cowling, Elizabeth. The cello. NY: Scribner, 1975. ISBN 0684141272

- Pleeth, William, and Nona Pyron. Cello. NY: Schirmer Books, 1982. ISBN 0028720504

- Prieto, Carlos, and Elena C. Murray. The adventures of a cello. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006. ISBN 0292713223

External links

All links retrieved January 20, 2017.

- The Internet Cello Society: an online community of cellists; includes several forums.

- cellist.nl: An international register of professional cellists, teachers, and students.

- Cello History: A brief history of the cello.

- Experimental Electric Violoncello at oddmusic.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.