The Eighty Years' War, or Dutch Revolt (1568–1648), was the revolt of the Seventeen Provinces in the Netherlands against the Spanish king. Spain was initially successful in suppressing the rebellion. In 1572 however, the rebels conquered Brielle, and the northern provinces became first de facto, and in 1648 officially, independent as the United Provinces of the Netherlands or Dutch Republic, which rapidly grew to become a world power through its merchant shipping and experienced a period of economic, scientific and cultural growth.

The Southern Netherlands, situated in modern-day Belgium, Luxembourg and Northern France, remained under Spanish rule. In 1648 large areas were lost to France. The continuous repression by the Spanish in the south caused many of its financial, intellectual and cultural elite to flee north, contributing in no small measure to the success of the Dutch Republic. The Westpalian Treaty that marked the end of the Eighty Years war, and of the Thirty Years’ War, became the basis of subsequent international law. It recognized the sovereignty of states, rather than of imperial blocks. Borders were settled, and each state was to be free to determine the religion of its subjects free from external control.

Effectively, religion became separate from the State, even in countries such as England, the Netherlands and the Scandinavian nations, where certain churches were established. Some see this as a negative development because religious values could be marginalized and even banished from the public into the private realm. However, others regard this as a positive step, allowing the spiritual and the temporal to occupy their specific ground but also, within the democratic societies that developed post-Westphalia, permitting people to freely express their distinctive religious views in the public square as valid contributions to debate in societies that value free-speech and constructive debate. Such free discussion forms the basis of civil society, allowing people to express their opinions so that social and political and moral consensus can be reached. Nobody's ideas, in this system, is privileged simply because they claim some state-given authority to be the arbitrator of moral thought.

Background

During the fourteenth and fifteenth century, the Netherlands had been united in a personal union under the Duke of Burgundy. Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, born in Ghent and raised in the Netherlands, inherited the Burgundian lands and the Spanish kingdom, which had become a worldwide empire with the Spanish colonization of the American continents. In 1556 Charles passed on his throne to his son Philip II of Spain. Philip, being raised in Spain, had no connection with the Netherlands. During Philip's reign, several circumstances caused growing dissatisfaction and unrest in the Netherlands.

Taxation

The Netherlands were an entrepreneurial and very wealthy region in the Habsburg empire. Under the reign of Charles V, the latter became a worldwide empire which was almost continuously at war: against France in the Italian Wars, against the Turks in the Mediterranean Sea, and against Protestantism in Germany. The Netherlands paid heavily for these wars, but perceived them as unnecessary and sometimes harmful, because they were directed against some of their most important trading partners. Many nobles by now were not traditional aristocrats, but from families that had risen over the last centuries through trade and finance. They were alienated by these actions of the Spanish kings, which put their fortunes at risk. It was at this time that the Dutch, along with the Portuguese and the Spanish alone among western nations, traded with Japan.

Protestantism

During the sixteenth century Protestantism rapidly gained ground in northern Europe. The Netherlands were not predominantly Protestant in the 1560s, but Protestants, mainly of the Reformed branch (followers of John Calvin constituted a significant minority and were tolerated by local authorities. In a society dependent on trade, freedom and tolerance were considered essential. Charles V and Philip II, however, felt it was their duty to fight Protestantism, which led to increasing grievances in the Netherlands. In the second half of the century, the situation escalated. Philip sent troops and the hard Spanish repression turned the initial revolt into a fight for complete independence. Some Dutch Protestants called Philip the anti-christ, giving a distinctive religious stamp to rebellion against him (see Phillips 2005, 230).

The Dutch compared their more austere and thrifty Calvinist values favorably with the luxurious habits of Spain’s Catholic nobility. Symbolic stories from the New Testament, featuring fishermen, shipbuilders and simple occupations resonated among the Dutch. The Calvinist movement emphasized Christian virtues of modesty, cleanliness, frugality and hard work. The Protestant, Calvinist elements of the rebellion represented a moral challenge to the Spanish Empire.

Centralization

Although Brussels had become a de facto capital of the Netherlands in the fifteenth century, the nobility of the Netherlands and the wealthy merchant cities still had a large measure of autonomy. Philip II wanted to improve the management of his empire by increased authority of the central government in matters like law and taxes. The nobility and merchants alike were very suspicious of this.

Initial stages (1568-1572)

Iconoclasm and repression

On Assumption of the Virgin feast day in 1566 (usually marked a procession of a statue of Mary the mother of Jesus Christ), a small incident outside the Antwerp cathedral started a massive iconoclastic movement by the Calvinists. In the wake of the incident on August 15, they stormed the churches in the Netherlands and destroyed statues and images of Roman Catholic saints. According to Calvinist beliefs, statues represented the worship of false idols, which they believed to be heretical practices. Outraged at this desecration of his faith's churches, and fearing loss of control of the region, Philip II saw no other option than to send an army. In 1567 Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, marched into Brussels at the head of ten thousand troops.

The Duke of Alba had the counts of Egmont and Horne arrested for high treason, and the next year on June 5, 1568, they were decapitated on the Grand Place in Brussels. The Count of Egmont was a general and statesman of Flanders who came from one of the richest and most influential families in the Netherlands. He was Phillip II's cousin through his mother's side. The Count of Horne was a stadtholder (an official representative) of Guelders and an admiral of Flanders. In 1559 he commanded the stately fleet that conveyed Philip II from the Netherlands to Spain. Egmont and Horne were Catholic nobles who were loyal to the king of Spain until their death, and their executions were carried out because Alba considered they had been too tolerant towards Protestantism. Their death provoked outrage throughout the Netherlands. No fewer than 18,000 people were executed in the following six years of his governorship, according to some reports.[1] The events earned Alba the nickname "the Iron Duke."

William of Orange

William I of Orange was stadtholder of the provinces Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht, and Margrave of Antwerp. After the arrest of Egmont and Horne, he fled from the Burgundian Empire to the lands ruled by his wife's father—the Elector Count of Saxony. All his lands and titles in the Netherlands were forfeited and he was branded an outlaw.

In 1568 William returned to try and drive the highly unpopular Duke of Alba from Brussels. He did not see this as an act of treason against the king. This view is reflected in today's Dutch national anthem, the Wilhelmus, in which the last lines of the first stanza read: den koning van Hispanje heb ik altijd geëerd (“I have always honored the king of Spain”). The Battle of Rheindalen, which occurred on April 23, 1568, near Roermond, is often seen as the unofficial start of the Eighty Years' War. The Battle of Heiligerlee, commonly regarded as the beginning of the war, was fought on May 23, 1568.

Many cities were taken by the rebels, but the initial successes were in large part due to the drain on the garrisons caused by the simultaneous war that Spain was fighting against the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean Sea. After their victory in the Battle of Lepanto (1571), the Spanish were able to send more troops to the Netherlands and suppress the rebellion. William of Orange stayed at large and was from then on seen as the leader of the rebellion.

Resurgence (1572–1585)

By 1572 the Spanish had mostly suppressed the rebellion throughout the Netherlands. Alba's proposal to introduce a new tax, the "tenth penny," aroused great protest from both Catholics and Protestants, and support for the rebels grew. With the capture of Brielle by the Sea Beggars on April 1, 1572, the rebels gained a foothold in the north. This was a sign for protestants all over the Low Countries to rebel once more.[1]

Most of the important cities in the county Holland declared loyalty to the rebels. A notable exception was Amsterdam, which remained a loyal catholic city until 1578. William of Orange was put at the head of the revolt. The influence of the rebels rapidly growing in the northern provinces brought the war into a second and more decisive phase.

Pacification of Ghent

Being unable to deal with the rebellion, in 1573 Alba was replaced by Luis de Requesens and a new policy of moderation. Spain, however, had to declare bankruptcy in 1575 and was unable to pay its soldiers, who then mutinied*mdash;and in November 1576 sacked Antwerp at the cost of some eight thousand lives. This so-called "Spanish Fury" confirmed the rebels in the 17 provinces in their determination to take their fate in their own hands.

A peace was negotiated in the Pacification of Ghent, which stipulated a retreat of the Spanish army and religious tolerance from both sides. The Calvinists however failed to respect this and Spain sent a new army under Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza. [1]

Unions of Atrecht and Utrecht

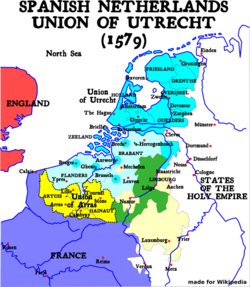

On January 6, 1579, prompted by the new Spanish governor Alessandro Farnese and upset by aggressive Calvinism of the Northern States, the Southern States (today mostly in France and part of Wallonia) signed the Union of Atrecht (Arras), expressing their loyalty to the Spanish king.

In response, William united the northern states of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders and the province of Groningen in the Union of Utrecht on January 23, 1579. Southern cities like Bruges, Ghent, Brussels and Antwerp joined the Union.

Oath of Abjuration

In 1581 the Oath of Abjuration was issued, in which the Netherlands proclaimed their independence from the king of Spain and formed the United Provinces of the Netherlands. After initial experiment, no suitable monarch was found and the civilian body States-General of the Netherlands took his place.

The fall of Antwerp

Immediately after the oath of abjuration, the Spanish sent an army to attempt to recapture the United Provinces. Over the following years Parma re-conquered the major part of Flanders and Brabant, as well as large parts of the northeastern provinces. The Roman Catholic religion was restored in much of this area. The important city of Antwerp fell into his hands, which caused most of its population to flee to the north. It has been calculated that Antwerp had about 100,000 inhabitants in 1570, but only about 40,000 in 1590.

On July 10, 1584, William I was assassinated by a supporter of Philip II. His son, Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange, would succeed him as leader of the rebellion.

The Netherlands was now split into an independent northern part, and the southern part under Spanish control. Because of the more or less uninterrupted rule of the Calvinist dominated "rebels," the northern provinces are thoroughly protestantized in the next decades. The south stays under Catholic Spanish rule, and remains Catholic to this day. The Spanish retained a large military presence in the south, where it could also be used against the French.

De facto independence of the north (1585–1609)

With the war going against them, the United Provinces sought help from France and England. The Dutch even offered them the monarchy of the Netherlands, which both declined.

England had unofficially been supporting the Dutch for years, and now decided to intervene directly. In 1585 under the Treaty of Nonsuch, Elizabeth I sent Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester to take the rule as lord-regent, with between five and six thousand troops, of which about one thousand were cavalry troops. The earl of Leicester proved not to be a successful commander. Neither did he understand the sensitive trade arrangements between the Dutch regents and the Spanish. Within a year after arrival, his credits with the population had been spent. Leicester returned to England, when the States-General, being unable to find any other suitable regent, appointed Maurice of Orange (William's son) Captain-General of the Dutch army in 1587, at the tender age of 20. This desperate appointment soon proved to be salvation of the pressured republic.

Under Maurice's leadership, the current borders of the present-day Netherlands were largely defined by the campaigns of the United Provinces. Besides Maurices' evident tactical talent, the Dutch successes (nicknamed the ten years of glory) were also due to the financial burden of Spain incurred in the replacement of ships lost in the disastrous sailing of the Spanish Armada in 1588, and the further need to refit its navy to recover control of the sea after the English counter attack. In 1595, when Henry IV of France declared war against Spain, the Spanish government declared bankruptcy again. However, by regaining control of the sea, Spain was able to greatly increase the supply of gold and silver from America, which allowed it to increase military pressure on England and France.

Under financial and military pressure, in 1598 Philip ceded the Netherlands to Archduke Albert of Austria (1559-1621) and his wife Isabella, following the conclusion of the Treaty of Vervins with France. By that time Maurice had conquered the important fortifications of Bergen op Zoom (1588), Breda (1590), Zutphen, Deventer, Delfzijl and Nijmegen (1591), Steenwijk, Coevorden (1592) Geertruidenberg (1593) Grol, Enschede, Ootmarsum and Oldenzaal (1597). Note that this campaign was played out in the border areas of the current Netherlands, while the heartland of Holland did not see any warfare, allowing it to rush ahead into its “Dutch Golden Age.”

By now it had become clear that Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands was heavy. The power over Zeeland, meant that the northern Netherlands controlled and closed the estuary of the Scheldt, which was the entry to the sea for the important port of Antwerp. The port of Amsterdam benefited greatly from the blockade of the port of Antwerp, therefore the merchants in the north began to question the desirability of re-conquering Antwerp. A final campaign to control the Southern provinces coast region was launched against Maurice’s advice in 1600. Although dressed as a liberation of the Southern Netherlands, the campaign was mainly aimed at eliminating the threat to Dutch trade posed by the Spanish-supported Dunkirker Raiders. The Spanish strengthened their positions along the coast, leading to the battle of Nieuwpoort. Although the States-General army was victorious, Maurice stopped the ill-conceived march on Dunkirk and returned to the Northern Provinces. Maurice never forgave the regents, led by Johan van Oldenbarneveld (1543-1619), that he was sent on this mission. By now the separation of the Netherlands had become almost inevitable.

Twelve Years' Truce (1609–1621)

1609 saw the start of a ceasefire, afterward called the Twelve Years' Truce, between the United Provinces and the Spanish controlled southern states, mediated by France and England at The Hague. It was during this ceasefire the Dutch made great efforts to build their navy, which was later to have a crucial bearing on the course of the war.

During the truce, two factions emerged in the Dutch camp, along political and religious lines. On one side the Arminianists, prominent supporters listing Johan van Oldenbarnevelt and Hugo Grotius. They tended to be well-to-do merchants who accepted a less strict interpretation of the bible than the classical Calvinism, especially on the issue of predestination, contending that anyone can be saved. They were opposed by the more radical Gomarists, who supported the ever more popular prince Maurice. In 1617 the conflict escalated when the republicans pushed the "Sharp Resolution," allowing the cities to take measures against the Gomarists. Prince Maurice accused Van Oldenbarnevelt of treason, had him arrested and executed in 1619. Hugo Grotius fled the country after escaping from imprisonment in Castle Loevestein. The slumbering frictions between the new merchant-regent class and the more traditional military nobility had come to a violent eruption.

Final stages (1621–1648)

Dutch successes

In 1622 a Spanish attack on the important fortress town of Bergen op Zoom was repelled. In 1625 Maurice died while the Spanish laid siege to the city of Breda. His half-brother Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, took command of the army. The Spanish commander Ambrosio Spinola (1569-1630) succeeded in conquering the city of Breda (an episode immortalized by the Spanish painter Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) in his famous painting Las Lanzas). After that victory the tide started to change in favor of the Dutch Republic. Frederick Henry conquered 's-Hertogenbosch (the Duke's Forrest) in 1629. This town, largest in the northern part of Brabant, had been considered to be impregnable. Its loss was a serious blow to the Spanish.

In 1632 Frederick Henry captured Venlo, Roermond and Maastricht during his famous "March along the Meuse." Attempts in the next years to attack Antwerp and Brussels failed, however. The Dutch were disappointed by the lack of support they received from the Flemish population. By now a new generation had been raised in Flanders and Brabant that had been thoroughly reconverted to Roman Catholicism and now distrusted the Calvinist Dutch even more than they loathed the Spanish occupants.[2]

Colonial theater

As the European countries were starting to build their empires, the war between the countries extended to colonies as well. Fights for land were fought as far away as Macao, East Indies, Ceylon, Formosa (Taiwan), the Philippines, Brazil, and others. The main of these conflicts would become known as the Dutch-Portuguese War. In the Western colonies, Dutch allowed privateering by their captains in the Caribbean to drain the Spanish coffers, and fill their own. The most successful raid was the capture of the larger part of the Spanish treasure fleet by Piet Pieterszoon Hein (1577-1629) in 1628, which made him one of the folk heroes of the war. Phillips (2005) argues that Dutch shipbuilding skills were the most advanced of the time. This enabled them to gain mastery of the Seas, and to build up the largest trading empire until it was surpassed by the British. They had the “world's biggest shipyards” with more money passing through Amsterdam than any other city in the world (12). He describes this as their “wind and water hegemony” (ix). Their decline as a world power during the eighteenth century was due to colonial overreach (231).

Stalemate

It became increasingly clear to all parties in the conflict that the Spanish would never succeed in restoring their rule to the territories north of the Meuse-Rhine delta and that the Dutch Republic did not have the strength to conquer the South.

In 1639 Spain sent a second armada, reminiscent of the great fleet that sailed against England in 1588, bound for Flanders, carrying 20,000 troops to assist in a last large scale attempt to defeat the northern "rebels." The armada was decisively defeated by Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp in the Battle of the Downs. This victory had historic consequences far beyond the Eighty Years' War as it marked the end of Spain as the dominant sea power.

Peace

On January 30, 1648, the war ended with the Treaty of Münster between Spain and the Netherlands. This treaty was part of the European scale Treaty of Westphalia that also ended the Thirty Years' War. The Dutch Republic was recognized as an independent state and retains control over the territories that were conquered in the later stages of the war.

The new republic consists of seven provinces: Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, Overijssel, Friesland and Groningen. Each province is governed by its local Provincial States and by a stadtholder. In theory, each stadtholder was elected and subordinate to the States-General. However, the princes of Orange-Nassau, beginning with William I of Orange, became de facto hereditary stadtholders in Holland and Zeeland. In practice they usually became stadtholder of the other provinces as well. A constant power struggle, which already had shown its precursor during the Twelve Years' Truce, emerged between the Orangists, who supported the stadtholders, and the regent's supporters.

The border states, parts of Flanders, Brabant and Limbourg (that were conquered by the Dutch in the final stages of the war) were to be federally governed by the States-General. These were called Generality Lands (Generaliteitslanden), which consisted of Staats-Brabant (present North Brabant), Staats-Vlaanderen (present Zeeuws-Vlaanderen) and Staats-Limburg (around Maastricht).

Aftermath

Nature of the war

The Eighty Years' War began with a series of classical battles fought by regular soldiers and mercenaries. While successes for both parties were limited, costs were high. As the revolt and its suppression centered largely on issues of religious freedom and taxation, the conflict necessarily involved not only soldiers but also civilians at all levels of society. This may be one reason as to the resolve and subsequent successes of the Dutch rebels in defending cities. Given the involvement of all sectors of Dutch society in the conflict, a more-or-less organized, irregular army emerged alongside the regular forces. Among these were the geuzen (from the French word gueux meaning "beggars"), who waged a guerrilla war against Spanish interests. Especially at sea, geuzen troops were effective agents of the Dutch cause. Many of the characteristics of this war were precursors of the modern concept of "total war," most notably the fact that Dutch civilians were considered to be important targets.

Effect on the Low Countries

In the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, Charles V established the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands as an entity separate from France, Burgundy or the Holy Roman Empire. The Netherlands at this point was among the wealthiest regions in Europe, and an important center of trade, finance and art. The Eighty Years' War introduced a sharp breach in the region, with the Dutch Republic (the present-day Netherlands) growing into a world power (see Dutch Golden Age), and the Southern Netherlands (more or less present-day Belgium) losing all economic and cultural significance for centuries to come.

Effect on the Spanish Empire

The conquest of America made Spain into the leading European power of the sixteenth century. This brought them in continuous conflict with France and the emerging power England. In addition, the deeply religious monarchs Charles V and Philip II saw a role for themselves as protectors of the catholic faith against Islam in the Mediterranean and against Protestantism in northern Europe. This meant the Spanish Empire was almost continuously at war. Of all these conflicts, the Eighty Years' War was the most prolonged and had a major effect on the Spanish finances and the morale of the Spanish people, who saw taxes increase and soldiers not returning. The Spanish government had to declare several bankruptcies. The Spanish population increasingly questioned the necessity of the war in the Netherlands and even the necessity of the Empire in general. The loss of Portugal in 1640 and the peace of Westphalia in 1648, ending the war, were the first signs that the role of the Spanish Empire in Europe was declining.

Political implications in Europe

During the Middle Ages, monarchy was established as a divine right of kings; in other words, royalty was granted to the monarch by God. This, though, was contested by the church, for whom it was the pope who legitimated temporal power. Effectively, there was an ongoing power struggle between kings, who wanted to bypass the pope, and the pope, in whose opinion “The Church has one head; it was not a monster with two heads; its ruler [Christ's] Vicar [was] the Pope; and all kings were inferior to the Pope” (Howarth, 155). The Dutch revolt against their lawful king, most obviously illustrated in the oath of abjuration (1581), implied that the population could dispose of a king if he did not meet his responsibilities. Eventually this led to the Dutch Republic. The acceptance of this by the European powers in 1648 spread across Europe, fueling resistance against the divine power of kings. States rather than the personal jurisdictions, or empires, of rulers became the basic unit of sovereignty, and whether large or small they were of equal status. This has remained the basis of international law, giving all states the same level of representation in the United Nations (with the exception of the permanent members of the Security Council). Religious liberty also went hand in hand with this development, since it denied the pope or anyone else external to a state the ability to interfere in its religious affairs, unless citizens chose freely to accept his religious but not political authority.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Henry Kamen, Spain, 1469-1714: A Society of Conflict (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2005, ISBN 0582784646).

- ↑ Jonathan I. Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998, ISBN 0198207344).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Howarth, Stephen. The Knights Templar. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1991 (original 1982). ISBN 0880296631

- Discusses the relationship between kings' claims to rule by divine right, and the popes' claims to absolute temporal power.

- Phillips, Kevin. American Theocracy. Penguin Books, 2007 (original 2005). ISBN 067003486X

- Discusses the rise and decline of Dutch power and also the role played by religion in this process as a key to understanding developments within the U.S.A.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.