Egyptology as an academic discipline did not fully emerge until the nineteenth century with the translation of the Rosetta Stone. Yet interest, both amateur and academic, in Egyptian civilization and culture goes back as far as the Ancient Greeks. Fascination with all things Egyptian has led to plundering, desecration, and massive dissemination of the vast physical and cultural remains of ancient Egypt. In the latter part of the twentieth century, as academics and the Egyptian government asserted the importance of preservation and full understanding of Egyptian heritage, Egyptology became a recognized academic field of study.

The numerous sites remaining from this culture, including the great Pyramids of Giza, reveal not only their scientific knowledge but their spiritual beliefs and insights. Through the field of Egyptology, study of these unique archaeological sites can advance and preserve our knowledge of this significant civilization.

Definition

Egyptology is a specialized field of study, drawing on the practices of archaeology, history, antiquity, and Near Eastern Studies. Egyptology investigates the range of Ancient Egyptian culture (language, literature, history, religion, art, economics, and ethics) from the fifth millennium B.C.E. up to the end of Roman rule in the fourth century C.E. Because it is such a specialized discipline, Egyptologists usually spend a majority of their careers exclusively studying ancient Egyptian civilization.

A Brief Overview of Ancient Egyptian Civilization

Ancient Egypt was one of the longest and most advanced of ancient civilizations. Believed to have appeared as a unified state no earlier than 3300 B.C.E., it lasted for over three millennia, until about 300 B.C.E., and is categorized into nine different dynasty periods. Ancient Egyptian achievements in engineering are the most visible today; their pyramids and monuments are recognizable world-wide. But they also had a complicated irrigation technique that harnessed the power of the Nile River, a complicated writing system known today as hieroglyphics, complex labor organizations, and highly structured political and religious arrangements.[1]

Perhaps one of the best known traditions of the Egyptians was the practice of mummification. The Egyptian funeral was a complex ceremony including various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken to honor the dead. However, the practice also points out the stringent social stratification of ancient Egyptian society. Mummification was for the rich and prestigious, while the poor, who could not afford expensive tombs, were buried in shallow graves in the sand, and because of the natural, arid, dry environment they were often naturally mummified. For most of the civilization's existence, the main religion was polytheistic and had elements of naturalism in that certain natural phenomenon, such as the Nile River, the sun, and the moon, were all personified in different deities.

Antiquity Interest in Egypt

Curiosity with the Egyptian Empire dates back to the height of its influence in the region, almost three thousand years ago. Herodotus, the famous Greek "father of history" wrote numerous "tall-tales" that exemplified the mystique of the Egyptians.[2] The Romans who occupied Egypt for centuries were fascinated by the culture of the area and were the first to really propagate the plundering of Egyptian artifacts on a massive trade scale, although the plundering of tombs and riches had been transpiring since the first tombs were built. The real dissemination of Egyptian culture outside of the Mediterranean did not occur until the French occupation of the Nile Valley in the eighteenth century.

Beginnings of Modern Egyptology

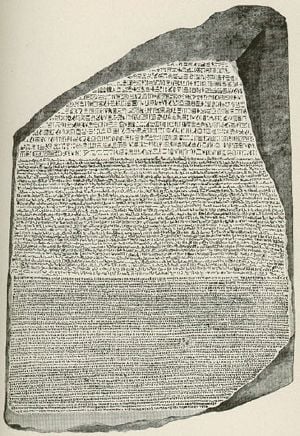

The small team of French scholars who studied Egypt in the nineteenth century published the first scientific volume called Description de l'Egypt.[3] The real French contribution, and perhaps one of the most important moments in Egyptology, was the translation of the written Egyptian language by Jean-Francois Champollion using the Rosetta Stone. By opening up the Egyptian language to widespread study, Champollion and other scholars of the time, such as Ippolito Rosellini and Karl Richard Lepsius helped usher in the age of antiquity studies in Egypt.[4]

In the early nineteenth century, control of Egypt switched to the British Empire and with it came a contradictory era of renewed scholarship and widespread plundering. Ironically, the plundering of Egyptian artifacts led directly to increased awareness of the need for in-depth academic study and conservation. Bernadion Drovetti and Giovanni Battista Belzoni both helped stock the Louvre, the Berlin Museum, the British Museum, and Turin Museum with the bulk of their Egyptian collections, as well as pieces that eventually made their way to other museums, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. Widespread display of the exotic artwork helped spread European interest in the region.

In 1858 Auguste Mariette was appointed to oversee all antiquities in Egypt. From that point on, all work in Egypt became more professional and disciplined. Many of the scholars moving to the area came from museum settings, either in Europe or in the major Egyptian cities of Luxor and Alexandria, where the predecessors of Egypt's modern day museums were already setup, and brought the meticulous attention to detail required in cataloging museum items to field work. One of the most significant persons during this time was William Matthew Flinders Petrie who developed many excavations and recording techniques that are still practiced by archaeologists today. During this time, such breakthroughs as the mapping of the pyramid architecture by Ludwig Borcharadt, the discovery of the pyramid texts by Emile Charles Adalbert Brugsch, and mass excavations in the Valley of the Kings all took place.[5]

Egyptology in the Twentieth Century

The twentieth century marked a watershed in the history of Egyptology. It began with the discovery the tomb of Tutankhamen by Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon, one of the most famous discoveries in Egyptology. Coinciding with the shifts in archaeological practices of preservation, and a new found respect for descendants of ancient cultures, came the end of colonial rule in Egypt.

Another major event in twentieth century Egyptology was the construction of the Aswan Dams, which were completed in 1902 and 1970. These projects led to many salvage operations, including the UNESCO project to relocate sites along the Nile River endangered by flooding. This included the moving and reassembling of the temple at Philae. In 1994, French archaeologist Jean-Yves Empereur was called in to examine the underwater site in the harbor of Alexandria prior to new construction. He discovered numerous architectural remains and statues, identifying some as belonging to the Pharos of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.[6]

Since the mid-twentieth century, the Supreme Council of Antiquities of the Egyptian Ministry of Culture has had complete control of all ancient Egyptian sites. Recognizing the importance of its heritage, the Egyptian government decided to take control of the areas that had been under foreign control and study for so many years, setting up its own institute to regulate Egyptological studies. So long dominated by European and American scholars, native Egyptian and Arab archaeologists began to become increasingly influential in the field, ushering in new perspectives and proposals about what ancient Egypt was actually like.

Foreign groups are still allowed to work in Egypt, under permit, and some of the most prestigious Egyptology institutes are run outside of Egypt, such as through the British Museum, Yale University, and the University of Pennsylvania, all of which now work closely with the Egyptian government. Study is still an important factor to the Egyptian government, but more so is conservation; a large part of Egyptology practiced in Egypt reflects the desire to preserve the remains of one of the most ancient human civilizations. Such practices as hunting down long stolen artifacts and negotiating the return of pieces kept in museums for years are examples of the ambitious conservation projects undertaken by the Ministry of Culture.

Contemporary Issues in Egyptology

Egyptology itself has come a long way from its beginnings. It is now a recognized course of study, usually at the graduate level, in most universities that have a well defined archaeology or Near Eastern studies department. However, the field is far from unified and there are many open problems concerning Ancient Egypt.

Egyptian archaeology is in a state of constant transition, with much of the terminology and chronology in dispute. The archaeological record is incomplete, with countless relics and artifacts missing or destroyed. New archaeological discoveries call into question previous conclusions about Ancient Egypt. Furthermore, there are internal problems of overall cohesion regarding various dynasties. There are also problems reconciling the Egyptian civilization with other concurrent civilizations.

Major Discoveries

Egyptologists have uncovered some of the most significant findings regarding early human civilization. Some examples include:

- The Rosetta Stone—opened the hieroglyphics of the Egyptians to interpretation and study, ushering in a more complete understanding of the culture.

- The Great Pyramids of Giza—one of the Seven Wonders of the World and easily the most recognizable of monuments in Egypt. They have been explored and excavated numerous times. Some of the most startling features discovered in the study of these pyramids include their alignment with the three stars that make-up Orion's Belt, the mathematical precision of their dimensions which highlights Egypt's advanced engineering achievements, as well their labor organizational systems.

- The Valley of the Kings—perhaps one of the most famous burial sites in the world. It is home to some of the most famous pharaohs and their illustrious tombs. It was at this site that the famous tomb of Tutankhamen was discovered.

- Tutankhamen's tomb—one of the few tombs ever found undisturbed, but also the first major discovery to be carried by the new technological breakthroughs of the broadcast media, helping to spread news of the discovery throughout the western world and re-establish the public's interest in Egypt. (The rumors of curses and strange occurrences surrounding the excavation also helped spread excitement over the discovery). Although Howard Carter's technique was meticulous for the day, his destructive autopsy of Tutankhamen’s body highlights how far Egyptology had to come before becoming a rigidly practiced discipline.

- Table of Abydos—a long list of the kings of the principal dynasties carved on a wall. It shows the cartouche name of every pharaoh of Egypt from the first, Menes, to the last dynasty.

A Select List of Famous Egyptologists

- Ludwig Borcharadt—One of the first scholars to fully map out the architectural designs of the pyramids.

- James Burton—Best known for his detailed sketches and recordings of Egyptian monuments during British colonial rule.

- Harry Burton—Took the first detailed photographs of famous monuments and sites.

- Giovanni Battista Belzoni—Helped excavate the Sphinx and was first to explore the Great Pyramids of Giza.

- Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge—Curator of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, for which he collected vast numbers of artifacts.

- Emile Charles Adalbert Brugsch—Discovered the pyramid texts.

- Jean-Francois Champollion—Discovered and translated the Rosetta Stone.

- Zhai Hawass—Perhaps the most famous Egyptologist of the late twentieth early twenty-first century, Hawass carried out extensive work in the Giza Valley and appeared on numerous television shows and educational films. He has been active in the movement to return many prominent Ancient Egyptian artifacts, such as the Rosetta Stone, to Egypt from collections around the globe in which they are in safekeeping. Hawass told the press "If the British want to be remembered, if they want to restore their reputation, they should volunteer to return the Rosetta Stone because it is the icon of our Egyptian identity."[7]

- Mark Lehner—American Egyptologist who worked closely with Zhai Hawass in regards to the Sphnix and Great Pyramid.[8]

- Karl Richard Lepsius—Early French scholar.

Notes

- ↑ Answers.com, Ancient Egypt. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Knox, Bernard, ed., "The Norton Book of Classical Literature." (New York: Norton, 1993)

- ↑ Egyptology Online, Egyptology: How it all Began. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Egyptology Online, Egyptology: How it all Began. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Dunn, Jimmy, The Egyptologists. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Nova online, Treasures of the Sunken City. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Edwardes, Charlotte, and Milner, Catherine, Egypt demands return of the Rosetta Stone. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ↑ Dunn, Jimmy, The Egyptologists. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bauval, Robert, and Adrian Gilbert. The Orion Mystery: Unlocking the Secrets of the Pyramids. Three Rivers Press 1995 (original 1993). ISBN 0517884542

- Childress, David H. Technology of the Gods: The Incredible Sciences of the Ancients. Adventures Unlimited. 2000. ISBN 0932813739

- Jacq, Christian. Magic and Mystery in Ancient Egypt. Souvenir Press, 1998. ISBN 0285634623

- Knapp, Ron. Tutankhamen and the Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. Julian Messner, 1979. ISBN 0671330365

- Manley, Bill, ed. The Seventy Great Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051232

- Mertz, Barbara. Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt. Dodd Mead. 1978. ISBN 0396075754

- Mertz, Barbara. Temples, Tombs and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt. Peter Bedrick Books, 1990. ISBN 0872262235

- Morris, Margaret. The Egyptian Pyramid Mystery Is Solved. Margaret Morris, 2004. ISBN 0972043403

- National Geographic Society. Mysteries of Egypt. 1999. ISBN 0792297520.

- Rhys-Davies, John. Riddles of the Monument Builders: Who Built the Sphinx? Time-Life Video. 1995.

- Sitchin, Zecharia. The Earth Chronicles Expeditions: Journeys to the Mythical Past. Bear & Co. 2004. ISBN 1591430364

- Swfte International. Archibald's Guide to the Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. 1995.

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

- Archaeological Institute of America. Archaeology Magazine

- Sussex Egyptology Society. Sussex Egyptology Society.

- Theban Mapping Project. Theban Mapping Project.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.