Emu

| Emu | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Dromaius novaehollandiae (Latham, 1790) | ||||||||||||||

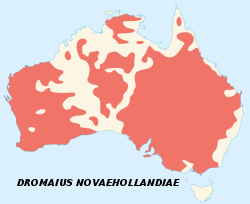

The emu has been recorded in the areas shown in pink.

| ||||||||||||||

|

Dromiceius novaehollandiae |

Emu is the common name for a large flightless Australian bird, Dromaius novaehollandiae, characterized by long legs with three-toed feet, long neck, stout body, small vestigial wings, brown to gray-brown shaggy plumage, and black-tipped feathers with black shafts. Reaching up to two meters (6.5 feet) in height, the emu is the largest bird native to Australia and the second-largest extant bird in the world by height, after its ratite relative, the ostrich. It is the only extant member of the genus Dromaius. The name emu also is used for extinct species belonging to the Dromaius genus, such as the Kangaroo Island emu (Dromaius baudinianus) and the King Island emu (Dromaius ater).

The emu is common over most of mainland Australia, although it avoids heavily populated areas, dense forest, and arid areas. Emus can travel great distances at a fast, economical trot and, if necessary, can sprint at 50 kilometers per hour (30 miles per hour) for some distance at a time (Davies 1963). They are opportunistically nomadic and may travel long distances to find food.

Emus provide important ecological and commercial function. Ecologically, they are integral to food chains, consuming a variety of plants and insects, and being consumed by foxes, dingoes, cats, dogs, predatory birds, and lizards (which consume their eggs). They also are important in seed dispersal. Commercially, emus are farmed for their meat, oil, and leather, and they also provide economic value by eating insects that are agricultural pests.

The emu subspecies that previously inhabited Tasmania became extinct after the European settlement of Australia in 1788. The distribution of the three extant mainland Australian subspecies of D. novaehollandiae has been influenced by human activities. Once common on the east coast, emu are now uncommon; by contrast, the development of agriculture and the provision of water for stock in the interior of the continent have increased the range of the emu in arid regions. The Kangaroo Island emu, a separate species, became extinct in the early 1800s, likely as a result of hunting and habitat deterioration.

Description

Emus are members of a group of birds known was ratites. Ratites are flightless birds characterized by a flat, raft-like sternum (breastbone) lacking the keel for attachment of wing muscles that is typical of most flying birds and some other flightless birds. In addition to emus, other ratites include ostriches, rheas, kiwis, and elephant birds.

Emus are large birds. The largest can reach up to two meters (6 feet 7 inches) in height and 1.3 meters (3.2 to 4.3 feet) at the shoulder). Emus weigh between 30 and 60 kilograms (66–132 pounds) (Ivory 1999).

They have small vestigial wings and a long neck and legs. Their ability to run at high speeds is due to their highly specialized pelvic limb musculature. Their feet have only three toes and a similarly reduced number of bones and associated foot muscles; they are the only birds with gastrocnemius muscles in the back of the lower legs. The pelvic limb muscles of emus have a similar contribution to total body mass as the flight muscles of flying birds (Patak and Baldwin 1998).

Emus have brown to gray-brown, soft-feathered plumage of shaggy appearance. A unique feature of the emu feather is its double rachis emerging from a single shaft. The shafts and the tips of the feathers are black. Solar radiation is absorbed by the tips, and the loose-packed inner plumage insulates the skin. The resultant heat is prevented from flowing to the skin by the insulation provided by the coat (Maloney and Dawson 1995), allowing the bird to be active during the heat of the day.

The sexes are similar in appearance.

On very hot days, emus pant to maintain their body temperature, their lungs work as evaporative coolers, and, unlike some other species, the resulting low levels of carbon dioxide in the blood do not appear to cause alkalosis (Maloney and Dawson 1994). For normal breathing in cooler weather, they have large, multifolded nasal passages. Cool air warms as it passes through into the lungs, extracting heat from the nasal region. On exhalation, the emu's cold nasal turbinates condense moisture back out of the air and absorb it for reuse (Maloney and Dawson 1998).

Their calls consist of loud booming, drumming, and grunting sounds that can be heard up to two kilometers away. The booming sound is created in an inflatable neck sac (AM 2001).

Distribution, ecology, and behavior

Emus live in most habitats across Australia, although they are most common in areas of sclerophyll forest and savanna woodland, and least common in populated and very arid areas. Emus are largely solitary, and while they can form enormous flocks, this is an atypical social behavior that arises from the common need to move towards food sources. Emus have been shown to travel long distances to reach abundant feeding areas. In Western Australia, emu movements follow a distinct seasonal pattern—north in summer and south in winter. On the east coast, their wanderings do not appear to follow a pattern (Davies 1976). Emus are also able to swim when necessary.

The population varies from decade to decade, largely dependent on rainfall; it is estimated that the emu population is 625,000–725,000, with 100,000–200,000 in Western Australia and the remainder mostly in New South Wales and Queensland (AM 2001).

Diet

Emus forage in a diurnal pattern. They eat a variety of native and introduced plant species; the type of plants eaten depends on seasonal availability. They also eat insects, including grasshoppers and crickets, lady birds, soldier and saltbush caterpillars, Bogong, and cotton-boll moth larvae and ants (Barker and Vertjens 1989). In Western Australia, food preferences have been observed in traveling emus: they eat seeds from Acacia aneura until it rains, after which they eat fresh grass shoots and caterpillars; in winter, they feed on the leaves and pods of Cassia; in spring, they feed on grasshoppers and the fruit of Santalum acuminatum, a sort of quandong (Davies 1963; Powell and Emberson 1990). Emus serve as an important agent for the dispersal of large viable seeds, which contributes to floral biodiversity (McGrath and Bass 1999; Powell and Emberson 1990).

Breeding and life cycle

Emus form breeding pairs during the summer months of December and January, and may remain together for about five months. Mating occurs in the cooler months of May and June. During the breeding season, males experience hormonal changes, including an increase in luteinizing hormone and testosterone levels, and their testicles double in size (Malecki 1998). Males lose their appetite and construct a rough nest in a semi-sheltered hollow on the ground from bark, grass, sticks, and leaves. The pair mates every day or two, and every second or third day the female lays one of an average of 11 (and as many as 20) very large, thick-shelled, dark-green eggs. The eggs are on average 134 x 89 millimeters (5.3 x 3.5 inches) and weigh between 700 and 900 grams (1.5–2 pounds) (RD 1976), which is roughly equivalent to 10–12 chicken eggs in volume and weight. The first verified occurrence of genetically identical avian twins was demonstrated in the emu (Bassett et al. 1999).

The male becomes broody after his mate starts laying, and begins to incubate the eggs before the laying period is complete. From this time on, he does not eat, drink, or defecate, and stands only to turn the eggs, which he does about 10 times a day. Over eight weeks of incubation, he will lose a third of his weight and will survive only on stored body-fat and on any morning dew that he can reach from the nest.

As with many other Australian birds, such as the superb fairy-wren, infidelity is the norm for emus, despite the initial pair-bond. Once the male starts brooding, the female mates with other males and may lay in multiple clutches; thus, as many as half the chicks in a brood may be fathered by others, or by neither parent as emus also exhibit brood parasitism (Taylor 2000). Some females stay and defend the nest until the chicks start hatching, but most leave the nesting area completely to nest again; in a good season, a female emu may nest three times (Davies 1976).

Incubation takes 56 days, and the male stops incubating the eggs shortly before they hatch (Davies 1976). Newly hatched chicks are active and can leave the nest within a few days. They stand about 25 centimeters tall and have distinctive brown and cream stripes for camouflage, which fade after three months or so. The male stays with the growing chicks for up to 18 months, defending them and teaching them how to find food (RD 1976).

Chicks grow very quickly and are full-grown in 12–14 months; they may remain with their family group for another six months or so before they split up to breed in their second season. In the wild, emus live between 10 to 20 years (PV 2006); captive birds can live longer than those in the wild.

Taxonomy

The emu was first described under the common name of the New Holland cassowary in Arthur Phillip's Voyage to Botany Bay, published in 1789 (Gould 1865). The species was named by ornithologist John Latham, who collaborated on Phillip's book and provided the first descriptions of and names for many Australian bird species. The etymology of the common name emu is uncertain, but is thought to have come from an Arabic word for large bird that was later used by Portuguese explorers to describe the related cassowary in New Guinea (AM 2001). In Victoria, some terms for the emu were Barrimal in the Djadja wurrung language, myoure in Gunai, and courn in Jardwadjali (Wesson 2001).

In his original 1816 description of the emu, Vieillot used two generic names; first Dromiceius, then Dromaius a few pages later. It has been a point of contention ever since which is correct; the latter is more correctly formed, but the convention in taxonomy is that the first name given stands, unless it is clearly a typographical error. Most modern publications, including those of the Australian government (AFD 2008), use Dromaius, with Dromiceius mentioned as an alternative spelling.

The scientific name for the emu is Latin for "fast-footed New Hollander."

Classification and subspecies

The emu is classified in the family with their closest relatives the cassowaries in the family Casuariidae in the ratite order Struthioniformes. However an alternate classification has been proposed splitting the Casuariidae into their own order Casuariformes.

Three different Dromaius species were common in Australia before European settlement, and one species is known from fossils. The small emus—Dromaius baudinianus and D. ater—both became extinct shortly after. However, the emu, D. novaehollandiae remains common. D. novaehollandiae diemenensis, a subspecies known as the Tasmanian emu, became extinct around 1865. Emus were introduced to Maria Island off Tasmania and Kangaroo Island near South Australia during the twentieth century. The Kangaroo Island birds have established a breeding population there. The Maria Island population became extinct in the mid-1990s.

There are three extant subspecies in Australia:

- In the southeast, D. novaehollandiae novaehollandiae, with its whitish ruff when breeding

- In the north, D. novaehollandiae woodwardi, slender and paler

- In the southwest, D. novaehollandiae rothschildi, darker, with no ruff during breeding

Relationship with humans

Conservation status

Emus were used as a source of food by indigenous Australians and early European settlers. Aborigines used a variety of techniques to catch the bird, including spearing them while they drank at waterholes, poisoning waterholes, catching Emus in nets, and attracting Emus by imitating their calls or with a ball of feathers and rags dangled from a tree (RD 1976). Europeans killed emus to provide food and to remove them if they interfered with farming or invaded settlements in search of water during drought. An extreme example of this was the Emu War in Western Australia in 1932, when emus that flocked to Campion during a hot summer scared the town’s inhabitants and an unsuccessful attempt to drive them off was mounted. In John Gould's Handbook to the Birds of Australia, first published in 1865, he laments the loss of the emu from Tasmania, where it had become rare and has since become extinct; he notes that emus were no longer common in the vicinity of Sydney and proposes that the species be given protected status (Gould 1865). Wild emus are formally protected in Australia under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Although the population of emus on mainland Australia is thought to be higher now than before European settlement (AM 2001), some wild populations are at risk of local extinction due to small population size. Threats to small populations include the clearance and fragmentation of areas of habitat; deliberate slaughter; collisions with vehicles; and predation of the young and eggs by foxes, feral and domestic dogs, and feral pigs. The isolated emu population of the New South Wales North Coast Bioregion and Port Stephens is listed as endangered by the New South Wales Government (DEC 2005).

Economic value

The Emu was an important source of meat to the Aborigines in the areas to which it was endemic. Emu fat was used as bush medicine, and was rubbed on the skin. It also served as a valuable lubricant. It was mixed with ochre to make the traditional paint for ceremonial body adornment, as well as to oil wooden tools and utensils such as the coolamon (Samemory 2008).

An example of how the emu was cooked comes from the Arrernte of Central Australia who call it Kere ankerre (Turner 1994):

Emus are around all the time, in green times and dry times. You pluck the feathers out first, then pull out the crop from the stomach, and put in the feathers you've pulled out, and then singe it on the fire. You wrap the milk guts that you've pulled out into something [such as] gum leaves and cook them. When you've got the fat off, you cut the meat up and cook it on fire made from river red gum wood.

Commercial emu farming started in Western Australia in 1987, and the first slaughtering occurred in 1990 (O'Malley 1998). In Australia, the commercial industry is based on stock bred in captivity and all states except Tasmania have licensing requirements to protect wild emus. Outside Australia, emus are farmed on a large scale in North America, with about 1 million birds raised in the United States (USDA 2006), as well as in Peru, and China, and to a lesser extent in some other countries. Emus breed well in captivity, and are kept in large open pens to avoid leg and digestive problems that arise with inactivity. They are typically fed on grain supplemented by grazing, and are slaughtered at 50–70 weeks of age. They eat two times a day and prefer 5 pounds of leaves each meal.

Emus are farmed primarily for their meat, leather, and oil. Emu meat is a low-fat, low-cholesterol meat (85 mg/100 grams); despite being avian, it is considered a red meat because of its red color and pH value (USDA 2005, 2006). The best cuts come from the thigh and the larger muscles of the drum or lower leg. Emu fat is rendered to produce oil for cosmetics, dietary supplements, and therapeutic products. There is some evidence that the oil has anti-inflammatory properties (Yoganathan 2003); however, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration regards pure emu oil product as an unapproved drug. Emu leather has a distinctive patterned surface, due to a raised area around the feather follicles in the skin; the leather is used in such small items as wallets and shoes, often in combination with other leathers.

The feathers and eggs are used in decorative arts and crafts.

Cultural references

The emu has a prominent place in Australian Aboriginal mythology, including a creation myth of the Yuwaalaraay and other groups in New South Wales who say that the sun was made by throwing an emu's egg into the sky; the bird features in numerous aetiological stories told across a number of Aboriginal groups (Dixon 1916). The Kurdaitcha man of Central Australia is said to wear sandals made of emu feathers to mask his footprints.

The emu is popularly but unofficially considered as a faunal emblem—the national bird of Australia. It appears as a shield bearer on the Coat of Arms of Australia with the red kangaroo and as a part of the Arms also appears on the Australian 50 cent coin. It has featured on numerous Australian postage stamps, including a pre-federation New South Wales 100th Anniversary issue from 1888, which featured a 2 pence blue emu stamp, a 36 cent stamp released in 1986, and a $1.35 stamp released in 1994. The hats of the Australian Light Horse were famously decorated with an Emu feather plume.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Australian Faunal Directory (AFD). 2008. Australian Faunal Directory: Checklist for Aves. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Government. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Australian Museum (AM). 2001. Emu Dromaius novaehollandiae. Australian Museum. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Barker, R. D., and W. J. M. Vertjens. 1989. The Food of Australian Birds 1. Non-Passerines. CSIRO Australia. ISBN 0643050078.

- Bassett, S. M. et al. 1999. Genetically identical avian twins. Journal of Zoology 247: 475–78

- Davies, S. J. J. F. 1963. Emus. Australian Natural History 14: 225–29.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. 1976. The natural history of the Emu in comparison with that of other ratites. In H. J. Firth and J. H. Calaby (eds.), Proceedings of the 16th International Ornithological Congress. Australian Academy of Science. ISBN 0858470381.

- Department of Environment and Climate Change, New South Wales Government. 2002. Emu. New South Wales Government. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC), New South Wales. 2005. Emu population in the NSW North Coast Bioregion and Port Stephens LGA: Profile. New South Wales, Dept. of Environment and Conservation. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Dixon, R. B. 1916. Part V. Australia. In R. B. Dixon, Oceanic Mythology. Boston: Marshall Jones. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Gould, J. 1865. Handbook to the Birds of Australia, Volume 2. Landsdowne Press.

- Ivory, A. 1999. Dromaius novaehollandiae. Animal Diversity. Retrieved September 08, 2008.

- Malecki I. A., G. B. Martin, P. O'Malley, et al. 1998. Endocrine and testicular changes in a short-day seasonally breeding bird, the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), in southwestern Australia. Animal Reproduction Sciences 53:143–55 PMID 9835373. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Maloney, S. K, and T. J. Dawson. 1994. Thermoregulation in a large bird, the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. B, Biochemical Systemic and Environmental Physiology. 164: 464–72.

- Maloney, S. K., and T. J. Dawson. 1995. The heat load from solar radiation on a large, diurnally active bird, the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae). Journal of Thermal Biology 20: 381–87.

- Maloney, S. K, and T. J. Dawson. 1998. Ventilatory accommodation of oxygen demand and respiratory water loss in a large bird, the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), and a re-examination of ventilatory allometry for birds. Physiological Zoology 71: 712–19.

- McGrath, R. J., and D. Bass. 1999. Seed dispersal by Emus on the New South Wales north-east coast. EMU 99: 248–52.

- O'Malley, P. 1998. Emu farming. In K. W. Hyde, The New Rural Industries: A Handbook for Farmers and Investors. Canberra, Australia: Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (Australia). ISBN 0642246904.

- Parks Victoria (PV). 2006. Emu. Parks Victoria. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Patak, A. E., and J. Baldwin. 1998. Pelvic limb musculature in the emu Dromaius novaehollandiae (Aves: Struthioniformes: Dromaiidae): Adaptations to high-speed running. Journal of Morphology 238:23–37 PMID 9768501. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Powell, R., and J. Emberson. 1990. Leaf and Branch: Trees and Tall Shrubs of Perth. Perth, W.A.: Dept. of Conservation and Land Management. ISBN 0730939162.

- Reader's Digest (RD). 1976. Reader's Digest Complete Book of Australian Birds. Reader's Digest Services. ISBN 0909486638.

- Samemory. 2008. Emu hunting. South Australia Memory. Government of South Australia, State Library. 2008.

- Taylor, E. L. et al. 2000. Genetic evidence for mixed parentage in nests of the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae). Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 47: 359–64.

- Turner, M.-M. 1994. Arrernte Foods: Foods from Central Australia. Alice Springs: IAD Press. ISBN 0949659762.

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2005. Emu, full rump, raw. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 18. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2006. Ratites (Emu, ostrich, and rhea). USDA. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Wesson, S. C. 2001. Aboriginal Flora and Fauna Names of Victoria: As Extracted From Early Surveyors' Reports. Melbourne: Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages. ISBN 9957936001.

- Yoganathan, S., R. Nicolosi, T. Wilson, et al. 2003. Antagonism of croton oil inflammation by topical emu oil in CD-1 mice. Lipids 38:603–07. PMID 12934669. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.