Environmentalism

Environmentalism is a perspective that encompasses a broad range of views concerned with the preservation, restoration, or improvement of the natural environment; it covers from radical Arne Næss's biospheric egalitarianism called Deep ecology to more conservative ideas of sustainable development often discussed at the United Nations. Environmentalism often includes explicit political implications, and thus can serve as political ideology.

Since environmental issues are considered as outcomes of modernity, environmentalism often has a critique of modernity, which includes critical evaluations of the culture of mass-production and mass-consumption. Since environmental issues exist in the nexus of social, cultural, economic, political and natural spheres of human life, a narrow single ideological perspective cannot provide an adequate solution. The collaboration of scholars and professionals from diverse disciplines is indispensable in order to cope with the multifaceted complex problems of today. The study of practical environmentalism is generally split into two positions: the mainstream "anthropocentric" or hierarchic, and the more radical "ecocentric" or egalitarian.

The term "environmentalism" is associated with other modern terms such as "greening," "environmental management," "resource efficiency and waste minimization," "environmental responsibility," and Environmental ethics and justice. Environmentalism also entails emerging issues such as global warming and the development of renewable energy.

The natural world exists according to the principles of interdependence and balance. Environmentalists calls attention to the effects of the rapid development of modern civilization that have disrupted the balance of the earth.

Environmental movement

The Environmental movement (a term that sometimes includes the conservation and green movements) is a diverse scientific, social, and political movement. In general terms, environmentalists advocate the sustainable management of resources, and the protection (and restoration, when necessary) of the natural environment through changes in public policy and individual behavior. In its recognition of humanity as a participant in ecosystems, the movement is centered around ecology, health, and human rights. Additionally, throughout history, the movement has been incorporated into religion. The movement is represented by a range of organizations, from the large to grassroots, but a younger demographic than is common in other social movements. Due to its large membership which represents a range of varying and strong beliefs, the movement is not entirely united.

Preservation, conservation, and sustainable development

There are some conceptual distinctions between preservation and conservation. Environmental preservation, primarily in the United States, is viewed as the strict setting aside of natural resources to prevent damage caused by contact with humans or by certain human activities, such as logging, mining, hunting, and fishing. Conservation, on the other hand, allows for some degree of industrial development within sustainable limits.

Elsewhere in the world the terms preservation and conservation may be less contested and are often used interchangeably.

Sustainable development is a pattern of resource use that aims to meet human needs while preserving the environment so that these needs can be met not only in the present, but in the indefinite future.

History

In Europe, it was the Industrial Revolution that gave rise to modern environmental pollution as it is generally understood today. The emergence of great factories and consumption of immense quantities of coal and other fossil fuels gave rise to unprecedented air pollution and the large volume of industrial chemical discharges added to the growing load of untreated human waste. [1] The first large-scale, modern environmental laws came in the form of the British Alkali Acts, passed in 1863, to regulate the deleterious air pollution (gaseous hydrochloric acid) given off by the Leblanc process, used to produce soda ash. Environmentalism grew out of the amenity movement, which was a reaction to industrialization, the growth of cities, and worsening air and water pollution.

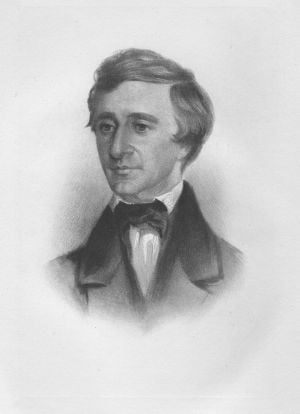

In the United States, the beginnings of an environmental movement can be traced as far back as 1739, when Benjamin Franklin and other Philadelphia residents, citing "public rights," petitioned the Pennsylvania Assembly to stop waste dumping and remove tanneries from Philadelphia's commercial district. The U.S. movement expanded in the 1800s, out of concerns for protecting the natural resources of the West, with individuals such as John Muir and Henry David Thoreau making key philosophical contributions. Thoreau was interested in peoples' relationship with nature and studied this by living a simple life close to nature. He published his experiences in the book Walden. Muir came to believe in nature's inherent right, especially after spending time hiking in Yosemite Valley and studying both the ecology and geology. He successfully lobbied congress to form Yosemite National Park and went on to set up the Sierra Club. The conservationist principles as well as the belief in an inherent right of nature were to become the bedrock of modern environmentalism.

In the twentieth century, environmental ideas continued to grow in popularity and recognition. Efforts were starting to be made to save some wildlife, particularly the American Bison. The death of the last Passenger Pigeon as well as the endangerment of the American Bison helped to focus the minds of conservationists and popularize their concerns. Notably in 1916 the National Park Service was founded by President Woodrow Wilson.

In 1949, A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold was published. It explained Leopold’s belief that humankind should have moral respect for the environment and that it is unethical to harm it. The book is sometimes called the most influential book on conservation.

In 1962, Houghton Mifflin published Silent Spring by American biologist Rachel Carson. The book cataloged the environmental impacts of the indiscriminate spraying of DDT in the U.S. and questioned the logic of releasing large amounts of chemicals into the environment without fully understanding their effects on ecology or human health. The book suggested that DDT and other pesticides may cause cancer and that their agricultural use was a threat to wildlife, particularly birds.[2] The resulting public concern lead to the creation of the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 which subsequently banned the agricultural use of DDT in the U.S. in 1972. The limited use of DDT in disease vector control continues to this day in certain parts of the world and remains controversial. The book's legacy was to produce a far greater awareness of environmental issues and interest into how people affect the environment. With this new interest in environment came interest in problems such as air pollution and oil spills, and environmental interest grew. New pressure groups formed, notably Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth.

In the 1970s, the Chipko movement was formed in India; influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, they set up peaceful resistance to deforestation by literally hugging trees (leading to the term "tree huggers") with the slogan "ecology is permanent economy."

By the mid-1970s, many felt that people were on the edge of an environmental catastrophe. The Back-to-the-land movement started to form and ideas of environmental ethics joined with anti-Vietnam War sentiments and other political issues. These individuals lived outside of society and started to take on some of the more radical environmental theories such as deep ecology. Around this time more mainstream environmentalism was starting to show force with the signing of the Endangered Species Act in 1973 and the formation of CITES in 1975.

In 1979, James Lovelock, a former NASA scientist, published Gaia: A new look at life on Earth, which put forth the Gaia Hypothesis; it proposes that life on Earth can be understood as a single organism. This became an important part of the Deep Green ideology. Throughout the rest of the history of environmentalism there have been debates and arguments between more radical followers of this Deep Green ideology and more mainstream environmentalists.

Today, the scope of environmentalism includes new global issues such as global warming.

Dark Greens, Light Greens, and Bright Greens

Contemporary environmentalists are often described as being split into three groups: Dark, Light, and Bright Greens.[3]

Light Greens see protecting the environment first and foremost as a personal responsibility. They fall in on the reformist end of the spectrum introduced above, but light Greens do not emphasize environmentalism as a distinct political ideology, or even seek fundamental political reform. Instead they often focus on environmentalism as a lifestyle choice.[3] The motto "Green is the new black." sums up this way of thinking, for many.[4]

In contrast, Dark Greens believe that environmental problems are an inherent part of industrialized capitalism, and seek radical political change. As discussed earlier, 'dark greens' tend to believe that dominant political ideologies (sometimes referred to as industrialism) are corrupt and inevitably lead to consumerism, alienation from nature and resource depletion. Dark Greens claim that this is caused by the emphasis on growth that exists within all existing ideologies, a tendency referred to as ‘growth mania’. The dark green brand of environmentalism is associated with ideas of Deep Ecology, Post-materialism, Holism, the Gaia Theory of James Lovelock and the work of Fritjof Capra. The division between light and dark greens was visible in the fighting between Fundi and Realo factions of the German Green Party. Since the Dark Greens often embrace strands of communist and marxist philosophies, the motto "Green is the new red." is often used in describing their beliefs.[5]

More recently, a third group may be said to have emerged in the form of Bright Greens. This group believes that radical changes are needed in the economic and political operation of society in order to make it sustainable, but that better designs, new technologies and more widely distributed social innovations are the means to make those changes—and that we can neither shop nor protest our way to sustainability.[6] As Ross Robertson writes, "[B]right green environmentalism is less about the problems and limitations we need to overcome than the “tools, models, and ideas” that already exist for overcoming them. It forgoes the bleakness of protest and dissent for the energizing confidence of constructive solutions."[7]

Free market environmentalism

Free market environmentalism is a theory that argues that the free market, property rights, and tort law provide the best tools to preserve the health and sustainability of the environment. This is in sharp contrast to the most common approach of looking to legislative government intervention to prevent destruction of the environment. It considers environmental stewardship to be natural, as well as the expulsion of pollutors and other aggressors through individual and class action.

Environmental organizations and conferences

Environmental organizations can be global, regional, national or local; they can be government-run or private (NGO). Several environmental organizations, among them the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Environmental Defense Fund, specialize in bringing lawsuits. Other environmentalist groups, such as the National Wildlife Federation, World Wide Fund for Nature, Friends of the Earth, the Nature Conservancy, and the Wilderness Society, disseminate information, participate in public hearings, lobby, stage demonstrations, and purchase land for preservation. Smaller groups, including Wildlife Conservation International, conduct research on endangered species and ecosystems. More radical organizations, such as Greenpeace, Earth First!, and the Earth Liberation Front, have more directly opposed actions they regard as environmentally harmful. The underground Earth Liberation Front engages in the clandestine destruction of property, the release of caged or penned animals, and other acts of sabotage.

On an international level, concern for the environment was the subject of a UN conference in Stockholm in 1972, attended by 114 nations. Out of this meeting developed UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) and the follow-up United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992. Other international organizations in support of environmental policies development include the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (NAFTA), the European Environment Agency (EEA), and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Books

Some notable books about environmentalist issues.

- Non-fiction

- High Tide : The Truth About Our Climate Crisis—Mark Lynas

- Crimes Against Nature—Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

- A Sand County Almanac—Aldo Leopold (1949, reprinted 1966)

- Desert Solitaire—Edward Abbey (1968)

- Silent Spring—Rachel Carson (1962)

- Walden—Henry David Thoreau

- The Everglades: River of Grass—Marjory Stoneman Douglas

- The Global Environmental Movement—John McCormick (1995)

- Encounters with the Archdruid—John McPhee

- Man and Nature—George Perkins Marsh (1864)

- The Consumer's Guide to Effective Environmental Choices: Practical Advice from the Union of Concerned Scientists—Michael Brower and Warren Leon (1999)

- The World According to Pimm—Stuart L. Pimm

- An Inconvenient Truth—Al Gore

- The Revenge of Gaia—James Lovelock

- Fiction

- Edward Abbey's The Monkey Wrench Gang

- Dr. Seuss's The Lorax

- Carl Hiaasen's children's novel Hoot

Popular music

Environmentalism has occasionally been the topic of song lyrics since the 1960s. Recently, a record label has emerged out of a partnership with Warner Music, which places environmental issues at its foundation. Green Label Records produces CDs using biodegradable paper, donates the proceeds of CD sales to environmental organizations, and plans tours using alternative fuels and carbon-neutral philosophies. It seeks to build a network of environmentally conscious musicians and music fans across North America.

Film and television

Within the last twenty years, commercially successful films with an environmentalism theme have been released theatrically and made by the major Hollywood studios. The Annual Environmental Media Awards have been presented by the Environmental Media Association (EMA) since 1991 to the best television episode or film with an environmental message.

Some notable films with an environmental message include:[8]

- Baraka (1992)

- FernGully: The Last Rainforest (1992)

- Erin Brockovich (2000)

- An Inconvenient Truth (2006)

- Happy Feet (2006)

- Captain Planet, Ted Turner's animated television series

Many anime movies by Hayao Miyazaki also suggest an environmentalist message. The best-known is Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, but Pom Poko as well as Princess Mononoke are based on the conflict between technology and nature.

See also

- Al Gore

- Deep ecology

- Ecology

- Environmental ethics

- Environmental science

- Global warming

- Henry David Thoreau

- Rachel Carson

Notes

- ↑ American Meteorological Society, History of the Clean Air Act. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ↑ Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Alex Steffen, Bright Green, Light Green, Dark Green, Gray: The New Environmental Spectrum World Changing, February 27, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ↑ Suzy Menkes, Eco-friendly: Why green is the new black International Herald Tribune, April 17, 2006. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ↑ Bill Butler, Fashion Update: Green Is the New Red Lew Rockwell, November 15, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ↑ Julie Newman (ed.), Green Ethics and Philosophy (SAGE Publications, Inc, 2011, ISBN 978-1412996877).

- ↑ Ross Robertson, A Brighter Shade of Green: Rebooting Environmentalism for the 21st Century Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ↑ Ken Eisner, The top 10 environmental films Straight.com, April 18, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, Terry L., and Donald Leal. Free Market Environmentalism. Westview Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0813311012

- Barton, Greg. American Environmentalism. American social movements. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0737710441

- Benthall, Jonathan. "Animal liberation and rights," Anthropology Today 23(2) (April 2007): 1.

- Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1962. ISBN 978-0395075067

- Dowie, Mark. Losing Ground: American Environmentalism at the Close of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0262041478

- Gottlieb, Robert. Environmentalism Unbound: Exploring New Pathways for Change. Urban and industrial environments. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0262072106

- Gottlieb, Roger S. A Greener Faith: Religious Environmentalism and Our Planet's Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 0195396200

- Newman, Julie (ed.). Green Ethics and Philosophy. SAGE Publications, Inc, 2011. ISBN 978-1412996877

- O'Riordan, Timothy. Environmentalism. Research in planning and design, 2. London: Pion, 1976. ISBN 978-0850860566

- Peterson del Mar, David. Environmentalism. Short histories of big ideas series. Harlow, England: Pearson/Longman, 2006. ISBN 978-0582772977

- Shutkin, William A. The Land That Could Be: Environmentalism and Democracy in the Twenty-First Century. Urban and industrial environments. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0262194358

- Verweij, Marco and Michael Thompson (eds.). Clumsy Solutions for a Complex World - Governance, Politics and Plural Perceptions. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 0230002307

External links

All links retrieved February 13, 2024.

- EnviroLink Network - A non-profit clearinghouse of environmental news and information

- A Brief History of Environmentalism GreenPeace

- Environmentalism Learning to Give

- The Social Dynamics of Environmentalism Association for Psychological Science

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.