The Fall of Man or the Human Fall, also called simply The Fall, is a theological doctrine describing the change of humankind's state from sinlessness to depravity. In Christian tradition, the Fall took place when Adam and Eve partook of the forbidden fruit and were expelled from the Garden of Eden, as recorded in the biblical book of Genesis. According to the teachings of Saint Paul and later Saint Augustine, this event was the Original Sin. It is the root of all the evil propensities and sins that have tainted their descendants—all human beings—throughout history. Various Christian traditions hold somewhat differing viewpoints regarding the extent to which the Fall affected human nature.

In Islam and Judaism, the events of Genesis 3 constituted the first human sin, but not the Fall in the normative Christian sense. Other religions and mythologies also describe a first sin or fall from grace.

The Fall of Man explains the persistence of human evil and explains the Christian assertion (often borne out in practice) that attempts to attain perfect goodness by human effort alone inevitably end in failure. Human beings need a Savior, who removes the root of original sin and thereby opens the path to reconciliation with God. This, according to Christian teaching, is the unique purpose of Jesus Christ, who, as a person not tainted by the Human Fall, comes into the world to destroy the power of evil over human life.

At the same time, the Fall of Man permits Christianity to reconcile the prevalence of evil in the world with the goodness of God, since it was the human beings, not God, who were responsible for the Fall. Furthermore, because humanity fell from an original state of blessedness, the doctrine of the Fall implies the possibility of restoration of that original blessedness. Therefore, it is ultimately an optimistic doctrine that ascribes to humans the identity of sons and daughters of God—in contrast to materialist theories that locate the propensity to aggression and criminality in the genes, making evil a permanent feature of human existence stemming from their animal forbearers.

Biblical account

According to Genesis 2, God created the first man, Adam, and placed him in the Garden of Eden. He caused all kinds of trees to grow in the Garden, including two special trees: the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. God told Adam that he was free to eat of any tree in the garden, but not of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. "In the day you eat of it, you will die," God warned (Gen. 2:17). Seeing that Adam was alone, God then created Eve out of his rib (Gen. 2:22). Adam names the animals and calls Eve "woman." They are both "naked and unashamed."

For a time, Adam and Eve obeyed the one commandment they have been given. However, one day, a serpent came to Eve and persuaded her to eat it. "God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened," he told her, "and you will be like God, knowing good and evil." The serpent showed Eve that the fruit was, "good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom," and so she ate it. She then gave some of the fruit to Adam, and he too ate. Adam and Eve immediately realized that they were naked, and became of ashamed of this, using fig leaves to cover their private parts.

In all the Abrahamic faiths, the serpent is linked with the figure of Satan, as in this New Testament verse: "That ancient serpent, who is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world…" (Revelation 12:9).

Soon after, God walked through the Garden looking for Adam and Eve, but he could not find them, because they were hiding from him. God called out to Adam: "Where are you" (Gen. 3:9). Adam responded, "I heard your voice, and I was afraid, because I was naked." God replied: "How did you know you were naked? Did you eat of the fruit of the tree I told you not to eat of?" By asking a question instead of judging and condemning him, God gave Adam the opportunity to own up to what he had done and repent. However Adam did not take responsibility for his action and instead put the blame on Eve. When God asked Eve a question, she too failed to take responsibility and instead she blamed the serpent. Since freedom and responsibility go hand in hand, when Adam and Eve denied they were responsible for their own actions, they denied they were free beings. In this way also they indicated that they were under the dominion of Satan.

As a result of these events, God cursed all three of the characters in the drama: The serpent must crawl on his belly and eat dust; the woman must suffer increased pain in childbearing and be ruled by her husband; and the man must labor for his food instead of eating freely of what grows in the Garden, for the land too is cursed. (Gen. 3:14-19) These curses can be seen as analogues to the blessings given earlier in Gen. 1:28.

However, the curse upon the serpent contains what Christian exegetes have long regarded as a hidden prophecy of Christ to come in the words, "He (the woman's seed) will bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel." (Gen. 3:15) This is said to foretell the crucifixion, by which Christ will strike the head of Satan while taking damage in his flesh.

God recognizes that the serpent's prophecy has come true: "The man has now become like one of us, knowing good and evil." (Gen 3:21) To prevent Adam from also partaking of the Tree of Life and living forever, God casts him out of the Garden, posting cherubim and a flaming sword to guard the entrance. The death that Adam and Eve underwent when they ate the fruit was a spiritual death—separation from God and His blessings. Physically, they lived for many more years.

Christian Views

Saint Paul is often credited for propounding the first definite doctrine of the Fall. "For as in Adam all die," he wrote, "so in Christ all will be made alive." (1 Corinthians 15:22) Although earlier Jewish writers had alluded to similar themes, the human inability to obey God's Law is a frequent and central theme in Paul's writings.

Catholic and Orthodox teaching hold to this basic Pauline doctrine of the Fall, as do most Protestants. There are differences of opinion, however, as to how drastically the Fall affected human nature. The formal doctrine of Original Sin, as articulated by Saint Augustine, holds that the Fall resulted in a fundamental change in human nature, so that all descendants of Adam and Eve are born in sin, which is transmitted through sexual intercourse. Humans are thus basically depraved and can only be redeemed by divine grace. The Eastern tradition generally took a somewhat more optimistic view holding that human nature was not totally depraved, while agreeing that without the Church and its sacraments, salvation is impossible. The Western tradition firmly rejected the even more optimistic view of Pelagianism, which taught that the Christian believer could attain spiritual perfection through moral efforts.

The Protestant Reformation, in its early stages, reaffirmed the strict Augustinian viewpoint, criticizing the Catholic Church for teaching that "works"—such as confession, fasting, penance, and indulgences—could produce salvation from sin, rather than "grace alone." Reformers such as John Wesley and his Methodism provided a greater role for human efforts in transforming one's character into a more Christ-like one. Nevertheless, they held that these efforts are efficacious only because they are grounded in Christ's saving grace, who by his sacrifice on the Cross redeems us of the sin of the Fall.

Contemporary Protestants hold a variety of views on the issue. Mainstream liberal theologians tend to interpret the Fall allegorically rather than historically. Some recent movements such as Christian Science reject the doctrine of the Fall altogether. Others, such as the Unification Church, reaffirm the importance of the Fall to understanding the human condition.

Other Interpretations

Judaism

Traditional Judaism, like Christianity, interprets the biblical account of Adam and Eve as historical, but does not interpret it as a Fall of Man in the sense that it fundamentally changed human nature. The rabbinical traditional holds the tendency to evil, called the yetzer harah, was part of the original nature of creation. Thus, the disobedience of Adam and Eve was simply the "first sin." It did not result in Original Sin in the sense of a depraved nature passed on generationally. Quite simply, because of Adam's actions, he and his wife were removed from the Garden, and were forced to work, suffer pain in childbirth, and die. However, even after expelling them, God provided that men who honor God and follow His laws would be rewarded, while those who acted wrongly would be punished.

Nevertheless, it is not altogether correct to say that the Fall had no place in Jewish tradition or the theology of the Talmudists. A definite notion of the Fall is absent from the Old Testament, however, and begins to appear only in the late Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha.[1] Anticipating Saint Paul, 2 Esdras 3:21 states: "The first Adam fell into sin and guilt, and, like him, all that were born of him." According to the Talmudic rabbis, the sin of Adam had certain grievous results. The Shekinah left earth after his fall (Gen. R. 19); he himself lost his personal splendor and gigantic stature; all men were doomed to die. Some rabbis viewed the Fall as sexual. Through the illicit sexual intercourse of Eve with the serpent, the nature of her descendants was corrupted (Shab. 146a). The Zohar agrees with several Talmudic sages in the view that Adam and Eve's sin strengthened the power of the evil inclination (yetzer harah) in the human heart:

If Adam had not sinned, he would not have begotten children from the side of the evil inclination, but he would have borne offspring from the side of the Holy Spirit. But now, since all the children of men are born from the side of the evil inclination, they have no permanence and are but short-lived, because there is in them an element of the ‘other side.’ But if Adam had not sinned and had not been driven from the Garden of Eden, he would have begotten progeny from the side of the Holy Spirit—a progeny holy as the celestial angels, who would have endured for eternity, after the supernal pattern. Since, however, he sinned and begat children outside the Garden of Eden, these did not take root. (Zohar, Genesis 61a)

Islam

Like Judaism, Islam rejects the Christian doctrine of original sin and sees the sin of Adam and Eve as having more limited effects than in Christian tradition. The Qur'anic account of the fall is recounted in Surahs 2:35-39 and 7:20-27. It reports that Adam was originally created as God's vice regent of the Earth. The angels were commanded to bow to him, and Adam was permitted to live in the Garden with his wife and eat what he wished. But Satan caused Adam and his wife to sin, so that God removed them from the Garden. Sura 7:22 says:

So he (Satan/Shaitan) misled them with deception; and when they tasted the tree, their wickedness became apparent to them, and they rushed to cover themselves with the leaves of the paradise; and their Lord called to them: "Did I not forbid you from that tree, and tell you that the devil is your clear enemy?"

However, Islamic tradition holds that after the first couple sinned, they repented and became true followers of God. Indeed, thereafter, Adam became a prophet and lived without any subsequent sin.

Felix Culpa (the fortunate fall)

One interpretation of the doctrine of the Fall is that it was necessary or predestined in order that humans might benefit from God's grace. "O felix culpa!" wrote medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas, [2] meaning that this loss of innocence was a fortunate because of the good that would come from it, such as the birth and incarnation of Christ, his death, Resurrection, and Second Coming, Judgment Day, and the eventual hope of Heaven. In the traditional Latin Mass and during the Easter Vigil the priest declares: O felix culpa quae talem et tantum meruit habere redemptorem—"O blessed fault that earned us so good and great a Redeemer."

The Forbidden Fruit

A key question in interpreting the Fall of Man is the meaning of the forbidden fruit. The fruit is often identified as an apple, although the Bible does not mention it as such. Other identifications include grape, fig, wheat, pomegranate, or citron. Most commentators, however, hold that the exact identity of the fruit is secondary to the issue of obedience. In this view, the Fall did not occur as a result of body chemistry, but was a spiritual change that happened as a result of Adam and Eve's rebellion.

Others, including some early Christian sects and rabbinical sages, considered that the Fall was the result of sexual intercourse between Eve and the Serpent, usually understood to symbolize Satan. The Infancy Gospel of James,[3] for example, quotes Joseph, the husband of the Virgin Mary, as seeing Mary's illegitimate pregnancy as tantamount to Eve's fall, saying:

Who has done this evil thing in my house, and defiled the virgin? Has not the history of Adam been repeated in me? For just as Adam was in the hour of his singing praise, and the serpent came, and found Eve alone, and completely deceived her, so it has happened to me also.[4]

Christianity traditionally teaches that the Original Sin is passed on through sexual intercourse, interpreting Psalm 51:5,

"I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me."

A condition that is the result of eating a literal fruit can hardly be passed down through the lineage. But the effects of illicit love can be.

Judaism includes numerous traditions about Satan (either in person or utilizing a serpent) seducing Eve. The Slavonic Book of Baruch, xcvii, says that the serpent had infused lust into the fruit, and when Eve ate it sexual desire was awakened in her. The Bahir, a Kabbalistic text, states: "The serpent followed Eve, saying, 'Her soul comes from the north, and I will therefore quickly seduce her.' And how did he seduce her? He had intercourse with her." (Bahir 199). In the Pirke d'Rab. Eliezer, Satan persuaded the serpent to act on his behalf and "Be my instrument, and through thy mouth will I utter a word which shall enable thee to seduce man" (Pirḳe R. El. xiii). In another tradition, Eve became the lover of Satan in the Garden of Eden, and Satan impregnated Eve to become the father of Cain (Pirḳe R. El. 13). The New Testament contains an echo of this idea in Jesus' statement, "You are from your father the Devil." (John 8:44)

Other early Christians held to a doctrine known as encratism, later declared to be a heresy, which taught that sex is forbidden to those who hope to attain spiritual perfection. An objection to this view is that Adam and Eve were blessed by God to "be fruitful and multiply" (Gen. 1:28), implying that God intended for them to engage in sexual relations. In the present era, some in the Greek Orthodox tradition hold that God originally intended Adam and Eve to multiply without sex. This confusion stems from overvaluing the ascetic practice of celibacy.

In Genesis 2:24, God granted to Adam and Eve the promise of marriage and sexual union: "they become one flesh." Nevertheless, Adam and Eve did not begin their family until after they were expelled from the Garden, when "Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain" (Gen. 4:1). The problem was not sexuality per se, but rather when and how it was to be consummated—whether in accordance with God's will or in violation of God's will. If eating the fruit symbolized sexual intercourse, then it means that Adam and Eve gained "knowledge" of sexual love from Satan, not God. Had Adam and Eve remained obedient to God's commandment, it is conceivable that they would have joined in a holy union under God's blessing within the Garden.

Other Traditions

According to the Greek myth of Pandora's Box, the gods gave the first created mortal girl, named Pandora, a box (or jar) and warned her not to open it. When she could not contain her curiosity and in disobedience to the command, she opened the box, it released every manner of the evil (death, sorrow, plague) into the world. Only hope (expectation of ills) was left inside when she managed to close it up again. A parallel to the Fall is evident, in that a deity gives the first woman a desirable object that held potential for great harm and a commandment not to partake of it. It is intriguing to interpret the "box" symbolically as the woman's sexual organ.

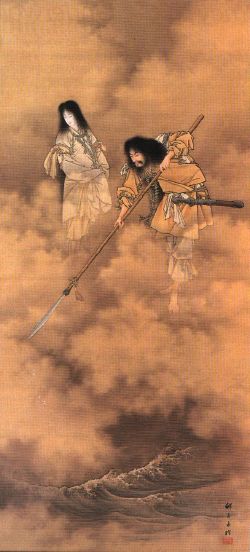

The Shinto creation myth in the Kojiki has been likened by the Japanese philosopher Kitaro Nishida to the Shinto version of the Human Fall. The deities Izanagi (male) and Izanami (female) were called to engage in ritual intercourse by which to procreate the islands and all creatures. However, they erred in allowing the woman to take the initiative, resulting in a still-born "leech-child." (Kojiki 4) Although they rectified their mistake by performing the ritual in the proper manner, the subsequent death of Izanami and the misfortunes that befell their offspring Amaterasu-omi-kami and Susano-o were punishments endured by the Shinto gods for this original mistake.[5]

Several traditional African myths describe a primordial distancing of the high god from humankind, sometimes involving a disobedient woman, sometimes about eating a fruit. A BaSonge tradition from Zaire has a man in the role of transgressor; the fruit is a banana; and death is the consequence:

The Creator, Fidi Mukullu, made all things including man. He also planted banana trees. When the bananas were ripe He sent the sun to harvest them. The sun brought back a full basket to Fidi Mukullu, who asked him if he had eaten any. The sun answered "no," and the Creator decided to put him to a test. He made the sun go down into a hole dug in the earth, then asked him when he wanted to get out. "Tomorrow morning, early," answered the sun. "If you did not lie," the Creator told him, "you will get out early tomorrow morning." The next day the sun appeared at the desired moment, confirming his honesty. Next the moon was ordered to gather God's bananas and was put to the same test. She also got out successfully. Then came man's turn to perform the same task. However, on his way to the Creator he ate a portion of the bananas, but denied doing so. Put to the same test as the sun and the moon, man said that he wanted to leave the hole at the end of five days. But he never got out. Fidi Mukullu said, "Man lied. That is why man will die and will never reappear."[5]

A parallel to the Fall of Man in the Buddhist scriptures is a story in the Ekottara Agama (a text from the Chinese Tripitaka) about how certain gods fell from heaven and became trapped in the world of gross matter after eating a sweet-smelling liquid. They became humans, lacking spirituality and filled with passion for one another. The gods who had not fallen reproached these fallen gods, which explains, the story goes, why love-making is regarded as a shameful thing, to be done in closed rooms.[5]

An anti-type of the Fall is found in some traditions of Gnosticism, in which the serpent is praised for bringing knowledge to Adam and Eve, and thereby freeing them from the control of the Demiurge, who created the physical world of illusion and evil. In this view it was not the true God, but the evil Demiurge who banished Adam and Eve, because man was now a threat. This echoes the myth of Prometheus, an angelic figure who disobeyed the gods—who wished to keep humans simple and subserviant—by bringing humans fire and thus freeing them to develop civilization.

Critical Views

Most biblical scholars regard the story of Adam and Eve in Genesis 2-3 as having been written by the Yahwist, or J, who lived in the tenth century B.C.E. around the time of King Solomon. The story was most likely composed in opposition to Canaanite mother-goddess worship, which employed sacred prostitutes in fertility rituals to induce the heavens to provide rain and abundant crops.[6] The goddess Asherah was central to this cult, and her worship, always denounced by the biblical prophets, was associated with trees (or wooden poles) and cultic sex (Deut. 23:17-18; 1 Kgs. 14:23-24; Hos. 4:12-14; Jer. 2:20). Thus, many scholars who favor a sexual interpretation of the story do not see it as a condemnation of sexuality, per se, but specifically of the Canaanite fertility cult.

Scholars have identified the term "knowledge of good and evil" as meaning sexual experience, notably in the Qumran text, the Rule of the Community: "He shall not come near to a woman, in order to have sexual relations with her, until his completing twenty years, when he knows good and evil" (1.9-11).[7] Several times in the book of Genesis, the verb "to know" implies carnal knowledge (Gen. 4:1, 19:5, 24:16). An important extrabiblical parallel is the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh, in which the hero's companion Enkidu is a type of Adam: Innocent and living wild among nature, he is seduced by a prostitute, after which he can no longer return to the wild, as the animals run away. Instead he gains a type of wisdom—she says to him, "Thou art wise, Enkidu, art become like a God" (1.4.35). Enkidu becomes ashamed of his body and enters the human world. Ultimately he dies, cursing the harlot who brought him out from his primordial state (7.3.10-30).

The serpent and the tree of life appear in another chapter of the Gilgamesh epic, in the episode in which the hero dives to the bottom of the waters to retrieve the "plant of life" that would make him immortal. However, while he rested from his labor, a serpent came and ate the plant, leaving Gilgamesh to reckon with his mortality. The serpent, which renews itself by shedding its skin, has long symbolized healing and renewal; the symbol of medicine to this day is the Caduceus, a pole with entwined serpents. The bronze serpent created as a healing icon by Moses (Numbers 21), meanwhile, may be none other than the life-giving serpent of more ancient semitic and Egyptian myths. Indeed this symbol was reportedly venerated in Jerusalem as late as the reign of King Hezekiah, (2 Kings 18).

Furthermore, in the fertility cult, Asherah was sometimes symbolized by a serpent. On Syrian and Egyptian plaques and statuettes of the goddess, she is depicted nude, her hair in flowing curls, standing on a lion and holding in her hands flowers and/or serpents.[8] As Asherah is the mother-goddess, Eve is called "mother of all the living" (Gen. 3:20), and her name, Ḥawwâ is related to an Aramaic word for serpent (ḥiwyat). Was Eve one of Asherah's names? One Punic inscription begins "O Lady Ḥawwat, Goddess." In a Ugaritic text that illuminates the connection between serpents and the fertility cult, RS 24.244, a goddess has shut herself in her house and demands of the god Horan that he give her serpents as a "bride price" ('tnn), which in the Hebrew Bible is etnān, the term for a harlot's hire. Only after he has offered her serpents does he enter her temple, and together they fulfill the sacred marriage to bring healing and fertility to the land. In this text, the serpent can bring either death (through snake-bite) or life and healing.

Mythologists such as Joseph Campbell and others hold that the Fall of Man sets earlier Near Eastern mythologies on their heads. The story of the Divine Lady Asherah and her life-giving Serpent was transformed into that of Eve, the first sinner, and the evil snake that tempted her against God's will.

The scene in Genesis 3 contains all the elements of the sacred marriage: The sacred ground of Eden, the tree as the cult-place of Lady Asherah and source of healing and fertility, the serpent as symbol and mediator of the cult, as well as of the male sexual organ, a woman called by one of Asherah's titles, and the man. Together they do something which is supposed to make the couple "like God," thus seeking what all those engaged in the ritual sex of the fertility cult were promised: Participation in the numinous power of uniting the cosmic male and female principles, mingling the human and divine energies to bring healing and fertility to the world. But just as in the Book of Numbers 25:1-15, where the Canaanite fertility cult promised healing but brought death, in Genesis 3 the results of the ritual sex are curses: Infertility, barren land, pain in childbirth, and death.

The Yahwist was inspired to place this story at the beginning of human history, as the original evil that caused humanity to be driven out of paradise. Set in primordial time, it is the opposite of creation. The chain of ever increasing evils continues through the opening chapters of Genesis as the Yahwist narrates Cain's murder of Abel, the violent generation of the Flood, and the hubris of the Tower of Babel, until in Genesis 12:2-3 God's blessing can enter the world anew through Abraham.

Notes

- ↑ Some argue that the laments of Job 3:3 and Jeremiah 20:14—cursing the day of these prophets' births—constitute a doctrine of Origin Sin, but these laments relate to particular circumstances in the prophets' lives, not to a sense of having been conceived in sin.

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica "III, 1, 3, ad 3," Article 3. Whether, if man had not sinned, God would have become incarnate? The Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas, Second and Revised Edition, 1920, Literally translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New Advent. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ↑ Also called the Protoevangelism of James, a second-century work that was widely read in the early church.

- ↑ Protoevangelism of James Translated by Alexander Walker. From Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 8, Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886). Revised and edited Kevin Knight. New Advent. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Andrew Wilson (ed.), World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts (Paragon House, 1998, ISBN 9781557787231), 305-307.

- ↑ J. Alberto Soggin, "Old Testament and Oriental Studies," Biblica et Orientalia 29 (Rome: Biblical Institute, 1975).

- ↑ Robert Gordis, Poets, Prophets and Sages (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1971, ISBN 0253166551), 199-201.

- ↑ James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near East in Pictures Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton University Press, 1974, ISBN 978-0691035024), plates 469-477.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blocher, Henri. Original Sin: Illuminating the Riddle. IVP Academic, 2001. ISBN 978-0830826056

- Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of God, Vol. 3: Occidental Mythology. Penguin (Non-Classics); Reissue edition, 1991. ISBN 978-0140194418

- Cassuto, Umberto, From Adam to Noah. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1978. ISBN 965223480X

- Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. Harvard University Press, 1973. ISBN 0674091760

- Dever, William G., Did God Have A Wife? Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005. ISBN 0802828523

- Gordis, Robert. Poets, Prophets and Sages: Essays in Biblical Interpretation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1971. ISBN 0253166551

- Harrison, Peter. The Fall of Man and the Foundations of Science. Cambridge University Press; 1 edition, 2007. ISBN 978-0521875592

- Pagels, Elaine. Adam, Eve, and the Serpent. New York: Vintage Books, 1989. ISBN 978-0679722328

- Pritchard, James B. Ancient Near East in Pictures Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton University Press, 1974. ISBN 978-0691035024

- Soggin, J. Alberto, "Old Testament and Oriental Studies," Biblica et Orientalia 29 Rome: Biblical Institute, 1975. ASIN B0040064KG

- Wily, Tatha. Original Sin: Origins, Developments, Contemporary Meanings. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2002. ISBN 0809141280

- Wilson, Andrew (ed.). World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts. Paragon House, 1998. ISBN 9781557787231

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.