Flatworm

| Flatworms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

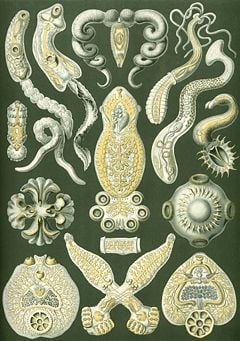

"Platodes" from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1909) | ||||

| Scientific classification | ||||

| ||||

| Classes | ||||

The flatworms are a phylum, Platyhelminthes, of relatively simple, soft-bodied, bilaterially symmetrical, invertebrate animals. The name of the phylum comes from the Greek platy, meaning "flat," and helminth, meaning "worm," which is indicative of their ribbon-shaped, flattened appearance. They include the flukes and tapeworms, among others.

Flatworms are acoelomates that are characterized by having three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) and lacking respiratory and circulatory systems. Acoelomates are invertebrates that do not have a coelom, or body cavity. With about 25,000 known species, flatworms are the largest phylum of acoelomates. Platyhelminths are thought to be the first invertebrates to have a third germ layer, the mesoderm (Towle 1989).

Flatworms are found in marine, freshwater, and even damp terrestrial environments. They generally are placed into four classes: Trematoda (flukes), Cestoda (tapeworms), Monogenea, and Turbellaria. While many flatworms are free living, many are also parasitic. Turbellarians, such as planarias, tend to be free-living, while trematodes, cestodes, and monogeneans live as parasites in, or on, other animals. Some of these parasites are ingested by consuming undercooked food.

Depending on species and age, individuals can range in size from nearly microscopic to over 20 meters long (some tapeworms can attain this length).

Description

A flatworm's soft body is ribbon-shaped, flattened dorso-ventrally (from top to bottom), and bilaterally symmetric. They are the simplest triploblastic animals with organs. This means their organ systems form out of three germ layers: An outer ectoderm and an inner endoderm, with a mesoderm between them.

Turbellarians generally have a ciliated epidermis, while cestodes and trematodes are covered with a cuticle (tough but flexible, non-mineral covering).

There is also no true body cavity (coelom) except the gut, and hence flatworms are acoelomates. The interior of the acoelomate body is filled with somewhat loosely spaced mesodermal tissue, called parenchyma tissue.

Flatworms have no true circulatory or respiratory system, but like all other animals, flatworms do take in oxygen. Extracellular body fluids (interstitial fluids) percolate between cells to help distribute nutrients, gases, and waste products. Flatworms respire at their integument; gases diffuse directly across their moist outer surface. This type of system is called integumentary exchange.

However, flatworms do have a bilateral nervous system; they are the simplest animals to have one. Two cord-like nerves branch repeatedly in an array resembling a ladder. Flatworms have their sense receptors and nerves concentrated on the anterior end (cephalization). The head end of some species even has a collection of ganglia acting as a rudimentary brain to integrate signals from sensory organs, such as eyespots.

Usually the digestive tract has one opening, so the animal cannot feed, digest, and eliminate undigested particles of food simultaneously, as most animals with tubular guts can. This gastrovascular cavity functions similarly to that of the Cnidaria. However, in a few particularly long flatworms, or those with highly branched guts, there may be one or more anuses. A small group where the gut is absent or non-permanent, called acoel flatworms, appear to be unrelated to the other Platyhelminthes.

Despite the simplicity of the digestive chamber, they are significantly more complex than cnidarians in that they possess numerous organs, and are therefore said to show an organ level of organization. The mesoderm allows for the development of these organs, as well as true muscle. Major sense organs are concentrated in the front end of the animals for species who possess these organs.

Muscular contraction in the upper end of the gut causes a strong sucking force, allowing flatworms to ingest their food and tear it into small bits. The gut is branched and extends throughout the body, functioning in both digestion and transport of food.

Behavior

Flatworms exhibit an undulating form of locomotion.

Flatworm reproduction is hermaphroditic, meaning each individual produces eggs and sperm. When two flatworms mate, they exchange sperm so both become fertilized. Some flatworms, such as Pseudobiceros hancockanus engage in penis fencing, in which two individuals fight, trying to pierce the skin of the other with their penises. The first to succeed inseminates the other, which must then carry and nourish the eggs.[1] They usually do not fertilize their own eggs.

Turbellarians classified as planarians (usually freshwater, non-parasitic) can also reproduce asexually by transverse fission. The body constricts at the midsection, and the posterior end grips a substrate. After a few hours of tugging, the body rips apart at the constriction. Each half grows replacements of the missing pieces to form two whole flatworms.

This also means that if a flatworm is cut in half, each half will regenerate into two separate, fully-functioning flatworms.

Classes

The traditional classifications of flatworms is primarily based on differing degrees of parasitism and divided into three monophyletic classes:

- Trematoda—Flukes

- Cestoda—Tapeworms

- Monogenea—Ectoparasitic flukes with simpler life cycles than Trematode flukes.

The remaining flatworms are grouped together for convenience as the class Turbellaria, now comprising the following orders:

- Catenulida

- Macrostomida

- Lecithoepitheliata

- Rhabdocoela

- Prolecithophora

- Proseriata

- Tricladida

- Polycladida

Most of these orders of Turbellaria include free-living forms. The flukes and tapeworms, though, are parasitic, and a few cause massive damage to humans and other animals.

Tapeworm infestations

Adult tapeworm infection is the infection of the digestive tract by parasitic cestodes, or tapeworms. Tapeworm larvae are sometimes ingested by consuming undercooked food. Once inside the digestive tract, the larva grows into an adult tapeworm, which can live for years and grow very large. Additionally, many tapeworm larvae cause symptoms in an intermediate host. For example, cysticercosis is a disease of humans involving larval tapeworms in the human body.

In a tapeworm infection, adult worms absorb food predigested by the host, so the worms have no need for a digestive tract or a mouth. Large tapeworms are made almost entirely of reproductive structures with a small "head" for attachment. Symptoms vary widely, depending on the species causing the infection.

Among the most common tapeworms in humans are the pork tapeworm, the beef tapeworm, the fish tapeworm, and the dwarf tapeworm. Infections involving the pork and beef tapeworms are also called taeniasis.

Taenia solium and Taenia saginata are common tapeworms. A person can become infected by these parasites by eating rare meat that has been infected. Symptoms generally include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and other gastrointestinal ailments. Sometimes, the parasite may migrate to the appendix, pancreas, or bile duct, causing severe abdominal pain.

A dangerous complication of the parasite Taenia solium, Cysticercosis, may occur when the larvae develop outside the intestinal tract. This parasite can move from the intestines to muscle tissue, bone marrow, fingers, and in some cases, the central nervous system (neurocysticercosis). The latter infection can lead to seizures and other neurological problems.

A third type of tapeworm, Diphyllobothrium latum, is contracted by eating raw, infected fish. The fish become infected by eating infected crustaceans, which became infected by consuming untreated sewage. This tapeworm results in symptoms similar to those of Taenia saginata and Taenia solium, but can also include weakness and fatigue.[2]

Biochemical Memory

In 1955, Thompson and McConnell conditioned planarian flatworms by pairing a bright light with an electric shock. After repeating this several times, they took away the electric shock, and only exposed them to the bright light. The flatworms would react to the bright light as if they had been shocked. Thompson and McConnell found that if they cut the worm in two, and allowed both worms to regenerate each half would develop the light-shock reaction.

In 1962, McConnell repeated the experiment, but instead of cutting the trained flatworms in two he ground them into small pieces and fed them to other flatworms. Incredibility, these flatworms learned to associate the bright light with a shock much faster than flatworms who has not been fed trained worms.

This experiment showed that memory could perhaps be transferred chemically. The experiment was repeated with mice, fish, and rats, but it always failed to produce the same results. Likewise, the findings with planarians could not be consistently replicated and thus are somewhat controversial. An explanation for this phenomenon in flatworms is still unknown today.

Notes

- ↑ PBS, The Shape of Life. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ↑ Healthline, The Health Experts Network. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Block, R. A, and J. V. McConnell. Classically conditioned discrimination in the Planarian, Dugesia dorotocephala. Nature 215 (1967): 1465-1466.

- Campbell, N. A. Biology, 4th ed. New York: Benjamin/Cummings Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0805319573

- Columbia University. The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Platyhelminthes. Columbia University Press, 2004. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- Crawley, J. L. and K. M. Van De Graff (eds.). A Photographic Atlas for the Zoology Laboratory, 4th edition. Colorado: Morton Publishing Company, 2002. ISBN 0895826135

- Evers, C. A. and L. Starr. Biology: Concepts and Applications, 6th ed. United States: Thomson, 2006. ISBN 0534462243

- McConnell, J. V. Memory transfer through cannibalism in planarium. J. Neuropsychiat. 3 suppl 1 (1962): 542-548.

- Naganuma, K. H. Acoelomate Flatworms, Phylum Platyhelminthes, (1997). Lab handout presented in the Fall of 1997. (adapted GNU Free Documentation Licensed text: Permission granted in February 2005).

- Thompson, R. and J. V. McConnell. Classical conditioning in planarian, Dugesia dorotocephala. J. Comp. Physiol. Psych. 48 (1955):65-68.

- Towle, A.Modern Biology. Austin: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1989. ISBN 0030139198

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.