| Part of a series on |

| Freedom |

| By concept |

|

Philosophical freedom |

| By form |

|---|

|

Academic |

| Other |

|

Censorship |

Freedom of assembly is the freedom to take part in any gatherings that one wishes. Closely associated with the rights of freedom of speech, expression, and association, it is held to be a key right in liberal democracies, whereby citizens may gather and express their views without government restrictions.

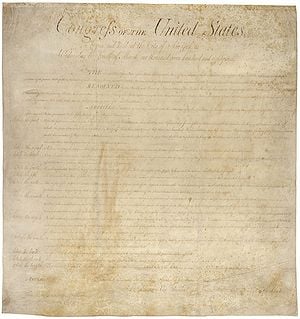

First specifically guaranteed in the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, freedom of assembly has since been recognized throughout the world as a fundamental human right. It was included in the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, Article 20 of which states: "Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association." Numerous other human rights conventions throughout the world have also included freedom of assembly.

Freedom of assembly, however, is not absolute. Most constitutional or legal provisions regarding this right specify that only peaceful assemblies are protected. Permits are sometimes required for assemblies in public places, and noise and traffic issues also limit the exercise of this right. Police are often authorized by law to disperse any crowd which threatens public safety. However, bureaucracies can abuse this power to prevent or disrupt assemblies that express unpopular political views or unorthodox religious ideas.

Communist, authoritarian, and Islamic nations often limit the right to freedom of assembly, due to the attitude of the states regarding political pluralism or religious freedom.

The importance of Freedom of Assembly

Freedom of assembly is generally recognized as one of the foundations of a democratic nation. Protecting this right is considered crucial for creating an open and tolerant society, in which different and often competing groups live together in a pluralistic environment. Freedom of assembly is also crucial to the development and expression of culture, as well as in the preservation of minority identities.

The right to freedom of assembly, however, is not absolute, but must be balanced against the need to protect other rights and needs. Thus, only peaceful assemblies are generally protected. On the other hand, peaceful assemblies that express offensive political messages or "heretical" religious ideas are generally protected under international law. For example, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) interprets the “peaceful” to include "conduct that may annoy or give offense to persons opposed to the ideas or claims that a particular assembly is promoting."

History in American tradition

Much of the early history of the establishment of the right to freedom of assembly played out in Anglo-American tradition. No right to free assembly was specified in the Magna Carta (1215), the Petition of Right (1628) and the English Bill of Rights (1689). Nevertheless, Englishmen often assembled to discuss their political grievances. Such gatherings were risky propositions, however. As in other monarchies, any such meeting was not only subject to suppression, but could also be interpreted as a treasonous act.

In religious matters, once the Church of England was established, other religious groups were prohibited from gathering in public and from using even private buildings for meetings or worship. Attempts at reform resulted in a law stipulating that no meeting of more than 50 persons could be held without gaining the permission of the king, unless a magistrate was present with the authority to arrest everyone present. The penalty for resisting the magistrate exercising this authority was death.

In practice, freedom of assembly became more widespread, both in England and continental Europe, as religious toleration spread in the eighteenth century. However, in the age of absolutism, assembly in opposition to the king was still a punishable offense.

Perhaps the first written guarantee of freedom of assembly was the Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights of 1776. It states: "The people have a right to assemble together, to consult for their common good."

The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen did not specify a right to freedom of assembly, but this right may be implied in the statements:

Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights… Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to society. Nothing may be prevented which is not forbidden by law…

Previously, the U.S. Declaration of Independence had stipulated only the rights of "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness," and the U.S. Constitution spoke vaguely of securing the "Blessings of liberty." It would be the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, however, that officially established the right of freedom of assembly for the American people and also set a standard that would be copied in many nations throughout the world. It states:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The U.S. courts would be busy over the following 200 years in interpreting the exact meaning of the freedom of assembly clause. Along with freedom of speech, the right of freedom of assembly has gradually broadened in scope over the years. Today, the standard for abridging the right of freedom of assembly in the U.S. is that such assemblies may only be banned or disrupted by the government only if a "clear and present danger" exists to the peace of society. The interpretation of this idea, however, has depended on circumstance. At times, for example, membership in various U.S. Communist groups was illegal, and during World War II, Japanese-Americans were placed in concentration camps. Today, however, freedom of assembly in the U.S. is more absolute.

In DeJonge v. Oregon (1937), a conviction under Oregon’s criminal syndicalism statute was determined to be unconstitutional because it was based on mere attendance at a meeting of the Communist Party. In NAACP v. Alabama (1958), the court held that state and federal governments may not adopt policies designed to discourage citizens from joining groups, even if the government believes the group to be undesirable. The ruling involved an attempt by the State of Alabama to force the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to reveal the names and addresses of its members in Alabama.

The freedom marches and other demonstrations of the 1960s Civil Rights movement provided other important test cases. In Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 52 black citizens had been arrested on April 12, 1963, after leaving their church and marching in an orderly fashion on the city's sidewalk in protest of segregation. In 1969, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, holding that his constitutional right to peaceably assemble had been violated by city authorities' implementation of an ordinance for the regulation of parades.

In 1977, U.S. Supreme Court ruled in National Socialist Party v. Skokie that Nazis had the right to march through a predominantly Jewish section of Skokie, Illinois, and that it was the responsibility of police to protect them from the outrage of local citizens.

Cases regarding the enforcement of curfews on gatherings of young persons have been decided differently in various U.S. states, and no uniform national standard has yet to emerge on this aspect of freedom of assembly.

Freedom of assembly in Europe

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, which extends to both Russia and the United States, holds that "freedom of peaceful assembly should, insofar as possible, be enjoyed without regulation." Under this standard, "anything not expressly forbidden in law should be presumed to be permissible, and those wishing to assemble should not be required to obtain permission to do so."

Moreover, it is the state’s duty to protect peaceful assembly, and this right must not be subject unduly to bureaucratic regulation. Laws restricting freedom of assembly must be compatible with international human rights law. The dispersal of assemblies should only be a measure of last resort.

In regulating freedom of assembly, the relevant authorities must not discriminate against any individual or group on any ground such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political opinion, or national origin. The freedom to organize and participate in public assemblies must be guaranteed to members of minority and indigenous groups including both nationals and non-nationals (including stateless persons, refugees, foreign nationals, asylum seekers, migrants, and tourists).

The implementation of these standards by members of the OSCE, however, varies considerably from country to country. In France, government opposition to "sects" reportedly results in discrimination against certain religious groups. For example, while a march in support of Palestinian rights was approved by Parisian authorities, a march for religious freedom by supporters of Scientology along the same route was banned. In Germany, hotels routinely refuse meeting rooms to groups on the basis of their political and religious views. The standard of allowing unpopular political groups the right to freedom of assembly is particularly problematic for Germany, which forbids the expression of Holocaust denial and outlaws Nazism. Russia, another OSCE member, has been the subject of numerous recent complaints regarding the freedom of assembly of religious minorities, gay organizations, and youth.

Around the world

Freedom of assembly has been enshrined in numerous international human rights documents throughout them world. Among them are:

- The 1948 American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man of the Organization of American States Article XXI declares:

Every person has the right to assemble peaceably with others in a formal public meeting or an informal gathering, in connection with matters of common interest of any nature.

- The 1950 European Convention on Human Rights, Article 11

Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests…

- The 1981 African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, Article 11 states:

Every individual shall have the right to assemble freely with others. The exercise of this right shall be subject only to necessary restrictions provided for by law in particular those enacted in the interest of national security, the safety, health, ethics and rights and freedoms of others.

- The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was scheduled to establish a human rights body in 2009.

Special problems regard the right to freedom of assembly are noted in the world's remaining Communist countries and in certain Islamic nations. Communist countries such as China, Laos, and North Korea do not allow freedom of assembly for political groups opposed to the government and also limit freedom of association for religious groups. An example receiving world attention was the repression of freedom of assembly in China by groups wishing to organize demonstrations during the 2008 Summer Olympics. Authoritarian nations elsewhere in the world also limit the freedom of assembly for political purposes. In many Islamic nations, non-Islamic religious groups are often severely limited in their right to organize public assemblies.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Martz, Carlton. Freedom of Assembly World History, U.S. History, and U.S. Government. Los Angeles: Constitutional Rights Foundation, 1988. OCLC 271261721.

- Rohde, Stephen F. Freedom of Assembly (American rights). New York: Facts On File, 2005. ISBN 9780816056637.

- Worton, Stanley N. Freedom of Assembly and Petition. Rochelle Park, NJ: Hayden Book Co, 1975. ISBN 9780810460096.

- Zick, Timothy. Speech Out of Doors: Preserving First Amendment Liberties in Public Places. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. ISBN 9780521517300.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.