French cuisine is a style of cooking derived from the nation of France. It evolved through centuries of social and political change. The Middle Ages heralded in lavish banquets among the upper classes with ornate, heavily seasoned food while the era of the French Revolution saw a move toward fewer spices and a more liberal use of herbs. More refined techniques for preparing French food developed with Marie-Antoine Carême, famed chef to Napoleon Bonaparte.

French cuisine was more fully developed in the late nineteenth century by Georges Auguste Escoffier and became what is now referred to as haute cuisine. Escoffier's major treatise on French cooking (Le Guide Culinaire), however, left out much of the regional character found in the provinces of France. The move to an appreciation of provincial French food began with the Michelin Guide (Le Guide Michelin) and the trend to gastro-tourism during the twentieth century.

National cuisine

French cuisine has evolved extensively over the centuries. Starting in the Middle Ages, a unique and creative national cuisine began forming. Various social movements, political movements, and the work of great chefs came together to create the techniques and style unique to French cooking renowned throughout the world. Through the years French cuisine has been given different names, and has been codified by various master-chefs. During their lifetimes these chefs have been held in high regard for their contributions to the culture of the country. The national cuisine which developed primarily in the city of Paris with the chefs to French royalty, eventually spread throughout the country and was ultimately exported overseas.

History

Middle Ages

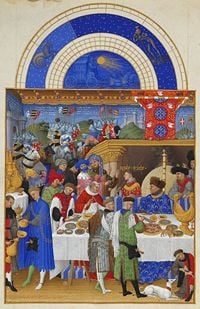

In French medieval cuisine, banquets were common among the aristocracy. Multiple courses would be prepared, but served in a style called service en confusion, literally 'all at once'. Food was generally eaten with the hands, meats being sliced off large pieces held between the thumb and two fingers. The sauces of the time were highly seasoned and thick, and heavily flavored mustards were used. Pies were also a common banquet item, with the crust serving primarily as a container, rather than as food itself, and it was not until the very end of the Late Middle Ages that the shortcrust pie was developed. Meals often ended with an issue de table, which later evolved into the modern dessert, and typically consisted of dragees (in the Middle Ages meaning spiced lumps of hardened sugar or honey), aged cheese and spiced wine, such as hypocras.[1]

Royalty and the 'New World'

During the ancien régime Paris was the central hub of culture and economic activity, and as such the most highly skilled culinary craftsmen were found there. Markets in Paris such as Les Halles, la Mégisserie, those found along Rue Mouffetard, and similar smaller versions in other cities were very important to the distribution of food. Those that gave French produce its characteristic identity were regulated by the guild system, which developed in the Middle Ages.

Guillaume Tirel, alias Taillevent, lived from 1310 – 1395 and was the chef to several French kings, including Philip VI, Charles V and Charles VI from around 1325. He wrote a famous book on cookery titled Le Viandier that was influential on subsequent books about French cuisine and important to food historians as a detailed source on the medieval cuisine of northern France. Today, many restaurants named "Taillevent" capitalize on the reputation of Guillaume Tirel.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, French cuisine assimilated many new food items from the New World. Although they were slow to be adopted, records of banquets show Catherine de' Medici serving 66 turkeys at one dinner.[2] The dish called cassoulet has its roots in the New World discovery of haricot beans, which are central to the dish's creation but had not existed outside of the New World until its exploration by Christopher Columbus.[3]

Haute cuisine

France's famous Haute cuisine — literally "high cuisine" — has its foundations during the seventeenth century with a chef named François Pierre La Varenne. As author of works such as Cvisinier françois, he is credited with publishing the first true French cookbook. His book includes the earliest known reference to roux using pork fat. The book contained two sections, one for meat days, and one for fasting. His recipes marked a change from the style of cookery known in the Middle Ages to new techniques aimed at creating somewhat lighter dishes, and more modest presentations.

La Varenne also published a book on pastry in 1667 entitled Le Parfait confitvrier (republished as Le Confiturier françois) which similarly updated and codified the emerging haute cuisine standards for desserts and pastries.[4]

The French Revolution

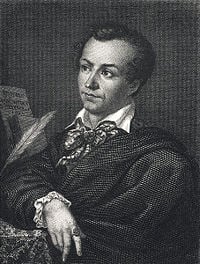

The Revolution was integral to the expansion of French cuisine, because it effectively abolished the guilds. This meant that any one chef could now produce and sell any culinary item he wished. Marie-Antoine Carême was born in 1784, five years before the onset of the Revolution. He spent his younger years working at a pâtisserie until being discovered by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord who would later cook for the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Prior to his employment with Talleyrand, Carême had become known for his pièces montèes, which were extravagant constructions of pastry and sugar architecture.[5]

More important to Carême's career was his contribution to the refinement of French cuisine. The basis for his style of cooking came from his sauces, which he named mother sauces. Often referred to as fonds, meaning foundations, these base sauces, espagnole, velouté, and béchamel are still prepared today.

The Brigade system - early twentieth century

Georges Auguste Escoffier, commonly acknowledged as the central figure to the modernization of haute cuisine, organized what would come to be regarded as the national cuisine of France. His influence began with the rise of some of the great hotels in Europe and America during the 1880s - 1890s. The Savoy Hotel owned by César Ritz was an early hotel Escoffier worked for, but much of his influence came during his management of the kitchens in the Carlton from 1898 until 1921. He created a system of parties called the brigade system, which separated the professional kitchen into five separate stations. These five stations included the garde manger that prepared cold dishes; the entremettier prepared soups, vegetables and desserts; the rôtisseur prepared roasts, grilled and fried dishes; the saucier prepared sauces; and the pâtissier prepared all pastry items. This system meant that instead of one person preparing a dish on their own, now multiple cooks would prepare the different components for each dish.[6]

Perhaps Escoffier's largest contribution to French cuisine was - his pièce de résistance- the publication of Le Guide Culinaire in 1903, which established the fundamentals of French cookery. Escoffier, who himself invented many new dishes, such as pêche Melba and crêpes Suzette updated Le Guide Culinaire four times during his lifetime.

Nouvelle cuisine - late twentieth century

The term nouvelle cuisine has been used many times in the history of French cuisine.[7] The first characteristic of nouvelle cuisine was a rejection of excessive complication in cooking. Secondly, the cooking times for most fish, seafood, game birds, veal, green vegetables and pâtés was greatly reduced in an attempt to preserve the natural flavors. Steaming became an important trend. Thirdly, using the freshest possible ingredients became of paramount importance. Additional changes included: larger menus being abandoned in favor of shorter menus; strong marinades for meat and game were cut down on; heavy sauces such as espagnole and béchamel thickened with roux were used less in favor of seasoning dishes with fresh herbs, butter, lemon juice, and vinegar. Regional dishes were drawn upon for inspiration instead of haute cuisine dishes of the past. New techniques were embraced and modern equipment was often used, including microwave ovens. Closer attention to the dietary needs of guests became important and, finally, chefs became extremely inventive and created new combinations and pairings.[7]

Some have speculated that a contributor to nouvelle cuisine was World War II when animal protein was in short supply during the German occupation.[8] No matter what the origins were, by the mid-1980s some food writers stated that the style of cuisine had reached exhaustion and many chefs began returning to the haute cuisine style of cooking, although much of the lighter presentations and new techniques remained.[7]

Regional Cuisine

Ingredients and dishes vary by region and some regional dishes have gained national popularity. Cheese and wine are a major part of the cuisine, playing different roles both regionally and nationally with their many variations and Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) (regulated appellation) laws.

French regional cuisine is characterized by a wide range of diversity and styles. Traditionally, each region of France has its own distinctive cuisine.

Paris • Ile-de-France

Paris and Ile-de-France are central regions where almost anything from the entire country is available as all train lines meet in the city. Over 5,000 restaurants exist in Paris and almost any cuisine from any country can be found. High-quality Michelin Guide rated restaurants proliferate here.[9]

Champagne • Lorraine• Alsace

Wild game and ham are popular in Champagne as well as the special sparkling wine simply known as Champagne. Fine fruit preserves come from Lorraine (region) as well as the famous Quiche Lorraine. Alsace is heavily influenced by the German food culture and therefore the wines and beers are very similar to the style of those bordering Germany.[10]

Nord • Pas de Calais • Picardy • Normandy • Brittany

The coastline supplies many crustaceans, sea bass, monkfish, and herring. Normandy has quality seafood such as scallops and sole, while Brittany has a supply of lobster, crayfish and mussels. Normandy, home to apple orchards, uses apples in many dishes such as cider and calvados. The northern areas of this region especially Nord, grow ample amounts of wheat, sugar beet and chicory. Thick stews are found in these northern areas as well. The produce, considered some of the best in the country, includes cauliflower and artichokes. Buckwheat grows widely in Brittany and is used in the region's galettes called jalet, which is where this dish originated.[11]

The Loire Valley • Central France

High quality fruits come from the Loire Valley and central France, including cherries grown for the liqueur Guignolet and the Belle Angevine pears. The strawberries and melons are also of high quality. Fish are seen in the cuisine as well as wild game, lamb, calves, Charolais cattle, Géline fowl, and high quality goat cheeses. Young vegetables are used often in the cuisine as are the specialty mushrooms of the region, champignons de Paris. Vinegars from Orléans are a specialty ingredient used as well.[12]

Burgundy • Franche-Comté

Burgundy is well known for its wines. Pike, perch, river crabs, snails, poultry from Bresse, Charolais beef or game, redcurrants, blackcurrants, honey cake, Chaource and Epoisses cheese are all specialties of the local cuisine of both Burgundy and Franche-Comté. Kir and Crème de Cassis are popular liquors made from black currants. Dijon mustard is also a specialty of Burgundy cuisine. Oils are used in the cooking here; types include nut oils and rapeseed oil. Smoked meat and specialties are produced in the Jura[13]

Lyon • Rhône-Alpes

Fruit and young vegetables are popular in the cuisine from the Rhône valley. Poultry from Bresse, guinea fowls from Drôme and fish from the Dombes lakes and mountains in Rhône-Alpes are key to the cuisine as well. Lyon and Savoy supply high quality sausages while the Alpine regions supply their specialty cheeses like Abondance, Reblochon, Tomme and Vacherin. Mères lyonnaises are a particular type of restaurateur relegated to this region that are the regions' bistro. Celebrated chefs from this region include Fernand Point, Paul Bocuse, the Troisgros brothers and Alain Chapel. The Chartreuse Mountains are in this region, and the famous liquor Chartreuse is produced in a monastery there.[14]

Poitou-Charentes • Limousin

Oysters come from the Oléron-Marennes basin while mussels come from the Bay of Aiguillon. High quality produce comes from the regions hinterland. Goat cheese is of high quality in this region and in the Vendée there is grazing ground for Parthenaise cattle, while poultry is raised in Challans. Poitou and Charente purportedly produce the best butter and cream in France. Cognac is also produced in the region along the Charente River. Limousin is home to the high quality Limousin cattle as well as high quality sheep. The woodlands offer game and high quality mushrooms. The southern area around Brive draws its cooking influence from Périgord and Auvergne to produce a robust cuisine.[15]

Bordeaux • Perigord • Gascony • Pays Basque

Bordeaux is well known for its wine, as it is throughout the southwest of France with certain areas offering specialty grapes for its wines. Fishing is popular in the region, especially the Pays Basque deep-sea fishing of the North Sea, trapping in the Garonne and stream fishing in the Pyrenees. The Pyrenees also support top quality lamb such as the "Agneau de Pauillac" as well as high quality sheep cheeses. Beef cattle in the region include the Blonde d'Aquitaine, Boeuf de Challose, Bazardaise, and Garonnaise. High quality free-range chickens, turkey, pigeon, capon, goose and duck prevail in the region as well. Gascony and Perigord cuisines includes high quality patés, terrines, confits and magrets. This is one of the regions famous for its production of foie gras or fattened goose or duck liver. The cuisine of the region is often heavy and farm based. Armagnac is also from this region as are high quality prunes from Agen.[16]

Toulouse • Quercy • Aveyron

Gers in this region offers high quality poultry, while La Montagne Noire and Lacaune area offers high quality hams and dry sausages. White corn is planted heavily in the area both for use in fattening the ducks and geese for foie gras as well as for the production of millas, a cornmeal porridge. Haricot beans are also grown in this area, which are central to the dish Cassoulet. The finest sausage in France is commonly acknowledged to be the saucisse de Toulouse, which also finds its way into their version of Cassoulet of Toulouse. The Cahors area produces a high quality specialty "black wine" as well as high-quality truffles and mushrooms. This region also produces milk-feed lamb. Unpasteurized ewe's milk is used to produce the Roquefort in Aveyron, while Cantal is produced in Laguiole. The Salers cattle produce quality milk for cheese, as well as beef items. The volcanic soils create flinty cheeses and superb lentils. Mineral waters are produced in high volume in this region as well.[17]

Roussillon • Languedoc • Cévennes

Restaurants are popular in the area known as Le Midi. Oysters come from the Etang de Thau, to be served in the restaurants of Bouzigues, Meze, and Sète. Mussels are commonly seen here in addition to fish specialties of Sète, Bourride, Tielles and Rouille de seiche. Also in the Languedoc jambon cru, sometimes known as jambon de montagne is produced. High quality Roquefort comes from the brebis (sheep) on the Larzac plateau. The Les Cévennes area offers mushrooms, chestnuts, berries, honey, lamb, game, sausages, pâtés and goat cheeses. Catalan influence can be seen in the cuisine here with dishes like brandade made from a purée of dried cod which is then wrapped in mangold leaves. Snails are also plentiful and are prepared in a specific Catalan style known as a cargolade. Wild boar can also be found in the more mountainous regions of the Midi.[18]

Provence • Côte d'Azur

The Provence and Côte d'Azur region is rich in quality citrus, vegetables and fruits and herbs. The region is one of the largest supplier of all of these ingredients in France. The region also produces the largest amount of olives and thus creates superb olive oil. Lavender is used in many dishes found in the Haute Provence. Other important herbs in the cuisine include thyme, sage, rosemary, basil, savory, fennel, marjoram, tarragon, oregano, and bay leaf. Honey is another prized ingredient in the region. Seafood proliferates in this area. Goat cheeses, air-dried sausage, lamb, and beef are also popular here. Garlic and anchovies can be seen in many of the sauces in the region and Pastis can be found in many of the bistros of the area. The cuisine uses a large amount of vegetables for lighter preparations. Truffles are commonly seen in Provence during the winter. Rice can be found growing in the Camargue, which is the most-northerly rice growing area in Europe, with Camargue red rice being a specialty.[19]

Corsica

Goats and sheep proliferate on the island of Corsica, kid goats and lamb are used to prepare dishes such as stufato, ragouts and roasts. Cheeses are also produced with brocciu being the most popular. Chestnuts, growing in the Castagniccia forest, are used to produce flour which in turn is used to make bread, cakes and polenta. The forest also provides acorns which are used to feed the pigs which provide most of the protein for the island's cuisine. As Corsica is an island, fresh fish and seafood are common in the cuisine as well. The island's pork is used to make fine hams, sausage and other unique items including coppa (dried rib cut), lonzu (dried pork fillet), figatella, salumu (a dried sausage) salcietta, Panzetta, bacon, figarettu (smoked and dried liverwurst) and prisuttu (farmer's ham). Clementines (hold an AOC designation), Nectarines and figs are grown there and candied citron is used in nougats, cakes, while the aforementioned brocciu and chestnuts are also used in desserts. Corsica also offers a variety of fruit wines and liqueurs, including Cap Corse, Cédratine, Bonapartine, liquer de myrte, vins de fruit, Rappu, and eau-de-vie de châtaigne.[20]

Specialties by Season

French cuisine varies according to the season. In summer, salads and fruit dishes are popular because they are refreshing and the fresh local produce is inexpensive and abundant. Green grocers prefer to sell their fruit and vegetables at lower prices if needed, rather than see them rot in the heat. At the end of summer, mushrooms become plentiful and appear in stews everywhere in France. The hunting season starts in September and runs through February. Wild game of all kinds is eaten, often in very elaborate dishes that celebrate the success of the hunt. Shellfish are at their peak as winter turns to spring, and oysters appear in restaurants in large quantities.

With the advent of deep-freeze and the air-conditioned hypermarché, these seasonal variations are less marked than previously, but they are still observed. Crayfish, for example, have a very short season and it is illegal to harvest them outside of that time period.[21]

Delicacies - "délicatesses"

Structure of meals

Breakfast

Le petit déjeuner (breakfast) is often a quick meal consisting of croissants, butter and jam, eggs or ham along with coffee or tea. Children often drink hot chocolate along with their breakfast. Breakfast of some kind is always served in cafés opening early in the day.

Lunch

Le déjeuner (lunch) was once a two hour mid-day meal but has recently seen a trend toward the one hour lunch break. In some smaller towns the two hour lunch may still be customary. Sunday lunches are often longer and are spent with the family.[22] Restaurants normally open for lunch at noon and close at 2:30 P.M. Many restaurants close on Saturday and Monday during the lunch hour.[23]

In large cities a majority of working people and students eat their lunch at a corporate or school cafeteria; it is therefore not usual for students to bring their own lunch food. It is common for white-collar workers to be given lunch vouchers as part of their employee benefits. These can be used in most restaurants, supermarkets and traiteurs; however workers having lunch in this way typically do not eat all three dishes of a traditional lunch due to price and time considerations. In smaller cities and towns, some working people leave their workplaces to return home for lunch, generating four rush hours during the day. Finally, a popular alternative, especially among blue-collar workers, is to lunch on a sandwich possibly followed with a dessert; both items can be found ready-made at bakeries and supermarkets at a reasonable cost.

Dinner

Le dîner (dinner) often consists of three courses, hors d'oeuvre or entrée (introductory course often soup), plat principal (main course), and a cheese course or dessert, sometimes with a salad offered before the cheese or dessert. Yogurt may replace the cheese course, while a normal everyday dessert would be fresh fruit. The meal is often accompanied by bread, wine and mineral water. Wine consumption by young people has been dropping in recent years. Fruit juice consumption has risen from 25.6 percent in 1996 to 31.6 percent in 2002. Main meat courses are often served with vegetables along with rice or pasta.[24] Restaurants often open at 7:30 P.M. for dinner and stop taking orders between the hours of 10:00 and 11:00 P.M. Many restaurants close for dinner on Sundays.[25]

Wine

Traditionally, France has been a culture of wine consumption. While this characteristic has lessened with time, even today, many French people drink wine daily. However, the consumption of low-quality wines during meals has been greatly reduced. Beer is especially popular with the young. Other popular alcoholic drinks include pastis, an aniseed flavored beverage drunk diluted with cold water, or cider.

The legal age for purchasing alcohol is 16; however, parents tend to prohibit their children from consuming alcohol before they reach early adulthood. While public consumption of alcohol is legal, driving under the influence can result in severe penalties.

Dining out

Places to dine out

- Restaurants - Over 5,000 in Paris alone, with varying levels of prices and menus. Open at certain times of the day, and normally closed one day of the week. Patrons select items from a printed menu. Some offer regional menus, while others offer a modern style menu. By law, a 'prix-fixe' menu must be offered, although high-class restaurants may try to conceal the fact. Few French restaurants cater to vegetarians. The Guide Michelin rates many of the better restaurants in this category.[26]

- Bistro(t) - Often smaller than a restaurant and may use a chalk board or verbal menu. Many feature a regional cuisine. Notable dishes include coq au vin, pot-au-feu, confit de canard, calves' liver and entrecôte.[26]

- Bistrot à Vin - Similar to caberets or tavernes of the past in France. Some offer inexpensive alcoholic drinks, while others take pride in offering a full range of vintage AOC wines. The foods are simple, including sausages, ham and cheese, while others offer dishes similar to what can be found in a bistro.[26]

- Bouchon - Found in Lyon, they produce traditional Lyonnaise cuisine, such as sausages, duck pâté or roast pork. The dishes can be quite fatty, and heavily oriented around meat. There are about twenty officially certified traditional bouchons, but a larger number of establishments describe themselves using the term.[27]

- Brasserie - French for brewery, these establishments were created in the 1870s by refugees from Alsace-Lorraine. These establishments serve beer, but most serve wines from Alsace such as Riesling, Sylvaner, and Gewürztraminer. The most popular dishes are Sauerkraut and Seafood dishes.[26] In general, a brasserie is open all day, offering the same menu.[28]

- Café - Primarily locations for coffee and alcoholic drinks. Tables and chairs are usually set outside, and prices marked up somewhat en terrasse. The limited foods sometimes offered include croque-monsieur, salads, moules-frites (mussels and pommes frites) when in season. Cafés often open early in the morning and shut down around nine at night.[26]

- Salon de Thé - These locations are more similar to cafés in the rest of the world. These tearooms often offer a selection of cakes and do not offer alcoholic drinks. Many offer simple snacks, salads, and sandwiches. Teas, hot chocolate, and chocolat à l'ancienne (a popular chocolate drink) is offered as well. These locations often open just prior to noon for lunch and then close late afternoon.[26]

- Bar - Based on the American style, many were built at the beginning of the twentieth century. These locations serve cocktails, whiskey, pastis and other alcoholic drinks.[26]

- Estaminet - Typical of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, these small bars/restaurants used to be a central place for farmers, mine or textile workers to meet and socialize. Alongside the usual beverages (beers, liquors…), one could order basic regional dishes, as well as play various indoor games. At one time, these estaminets almost disappeared, but are now considered a part of Nord-Pas-de-Calais history, and are therefore preserved and promoted.

Notes

- ↑ Barbara Ketcham Wheaton. Savoring the Past: The French Kitchen and Table from 1300 to 1789. (New York: First Touchstone, 1996. ISBN 978-0684818573), 1-7

- ↑ Wheaton, 81.

- ↑ Wheaton, 85.

- ↑ Wheaton, 114-120.

- ↑ Stephan Mennel. All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0252064906), 144-145

- ↑ Mennell, 157-159.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Mennell, 163-164.

- ↑ Nicholas Hewitt. The Cambridge Companion to Modern French Culture. (Cambridge: The Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0521794657), 109-110

- ↑ André Dominé, (ed.) Culinaria France. (Cologne: Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbh, 1998. ISBN 978-3833111297), 13

- ↑ Dominé, 55

- ↑ Dominé, 93.

- ↑ Dominé, 129, 132.

- ↑ Dominé, 153, 156, 166, 185.

- ↑ Dominé, 197, 230.

- ↑ Dominé, 237.

- ↑ Dominé, 259, 295.

- ↑ Dominé, 313.

- ↑ Dominé, 349, 360.

- ↑ Dominé, 387, 403, 404, 410, 416.

- ↑ Dominé, 435, 441, 442.

- ↑ However, imported crayfish are unrestricted, and many arrive from Pakistan; since they don't freeze well they are most often served seasonally

- ↑ Ross Steele. 1995. The French Way: Aspects of Behavior, Attitudes, and Customs of the French. (Lincolnwood, Ill: Passport Books. ISBN 0844214957), 82

- ↑ Fodor's See It France. 2009. (Fodors Travel Pubns. ISBN 1400007720), 342

- ↑ Steele, 82.

- ↑ Foder's, 342.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 Dominé, 30.

- ↑ Evelyne Boudou, and Jean-Marc Boudou. Les bonnes recettes des bouchons lyonnais. (Seyssinet: Libris, 2003. ISBN 9782847990027)

- ↑ Les brasseries ont toujours l'avantage d'offrir un service continu tout au long de la journée, d'accueillir les clients après le spectacle et d'être ouvertes sept jours sur sept, quand les restaurants ferment deux jours et demi par semaine. (Brasseries have the advantage of offering uninterrupted service all day, seven days a week, and of being open for the after-theater crowd, whereas restaurants are closed two and a half days of the week)—(Jean-Claude Ribaut in Le Monde, Feb. 9, 2007)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bertholle, Louisette. French Cuisine For All. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1980. ISBN 0385130872

- Boudou, Evelyne and Jean-Marc Boudou. Les bonnes recettes des bouchons lyonnais. Seyssinet : Libris, 2003. ISBN 978-2847990027

- Christian, Glynn, and Jenni Muir. Edible France: A Traveler's Guide. New York: Interlink Books, 1997. ISBN 156656221X

- Dominé, André, ed. Culinaria France. Cologne: Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbh, 2004 (original 1998). ISBN 978-3833111297

- Escoffier, Georges Auguste. Escoffier: The Complete Guide to the Art of Modern Cookery, Translated by H. L. Cracknell and R.J. Kaufmann. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2002 (original 1983). ISBN 978-0471290162

- Ferguson, Priscilla Parkhurst. Accounting for Taste: The Triumph of French Cuisine. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2004. ISBN 0226243230

- Foder's. See It. France, 2nd ed. New York: Foder's Travel Publications, 2009. ISBN 1400007720

- Hewitt, Nicholas. The Cambridge Companion to Modern French Culture. Cambridge: The Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0521794657

- Mennel, Stephan. All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present, 2nd ed., Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0252064906

- Montignac, Michel. The French Diet: The Secrets of why French Women Don't Get Fat. New York, NY: DK Publishing, 2005. ISBN 075661578X

- Sadowski, Jeffrey A. French Cuisine the Gourmet's Companion. New York: J. Wiley, 1997. ISBN 0585368066

- Spang Rebecca L., The Invention of the Restaurant, 2nd ed., Harvard University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0674006850

- Steele, Ross. The French Way: Aspects of Behavior, Attitudes, and Customs of the French. Lincolnwood, Ill: Passport Books, 1995. ISBN 0844214957

- Taillevent, and Terence Scully. The Viandier of Taillevent: An Edition of All Extant Manuscripts. [Ottawa]: University of Ottawa Press, 1988. ISBN 0776601748

- The Culinary Institute of America. The Professional Chef, 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, INC, 2006. ISBN 978-0764557347

- Wheaton, Barbara Ketcham. Savoring the Past: The French Kitchen and Table from 1300 to 1789. New York: First Touchstone, 1996. ISBN 978-0684818573

External links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

- French Palate Cleanser Recipes Frenchfood.about.com.

- One Recipe, Several Centuries Chezjim.com.

- French Cuisine DiscoverFrance.net.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.