| George Armstrong Custer | |

|---|---|

| December 5, 1839 - June 25 1876 (aged 36) | |

| |

| Place of birth | New Rumley, Ohio |

| Place of death | Little Bighorn, Montana |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Years of service | 1861-1876 |

| Rank | Brevet Major General |

| Commands held | Michigan Brigade 7th Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War *First Battle of Bull Run *Peninsula Campaign *Battle of Antietam *Battle of Chancellorsville *Gettysburg Campaign *Battle of Gettysburg *Overland Campaign **Battle of the Wilderness **Battle of Yellow Tavern *Valley Campaigns of 1864 *Siege of Petersburg Indian Wars *Battle of the Washita *Battle of the Little Bighorn |

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 ‚Äď June 25, 1876) was a United States Army cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. Promoted at an early age to the temporary rank of brigadier general, he was a flamboyant and aggressive commander during numerous Civil War battles, known for his personal bravery in leading charges against opposing cavalry. He led the Michigan Brigade, whom he called the "Wolverines," during the Civil War. He was defeated and killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn against a coalition of Native American tribes led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Just one year before, in 1875, he had sworn by White Buffalo Calf Pipe, a pipe sacred to the Lakota, that he would not fight Native Americans again.

Custer was as brash as he was brave, and some 300 books, 45 movies, and 1,000 paintings have captured his remarkable life and military career. The celebrated calvary man has had a city, county, highway, national forest, and school named in his honor. However, he was also known as a reckless commander whose successes were due as much to luck as to military skill.

In recent years, Custer's reputation has been tarnished by a re-evaluation of the Indian Wars, in which he played an important part. Long after his death, he lost a second battle on the same ground on which he had fought 70 years earlier. In 1946, President Harry S. Truman had honored the Little Bighorn battle site by naming it the Custer Battlefield National Monument, but later it was renamed the Little Big Horn Battlefield at the urging of Native Americans and others opposed to the glorification of Custer's "last stand."

Family and early life

Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio, to Emanuel Henry Custer (1806-1892), a farmer and blacksmith, and Maria Ward Kirkpatrick (1807-1882). Custer would be known by a variety of nicknames: Armstrong, Autie (his early attempt to pronounce his middle name), Fanny, Curley, Yellow Hair, and Son of the Morning Star. His brothers Thomas Custer and Boston Custer died with him at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, as did his brother-in-law and nephew; his other two full siblings were Nevin and Margaret Custer. There were several other half siblings. Originally his ancestry, named "K√ľster," came from Westphalia in Northern Germany. They emigrated and arrived in America in the seventeenth century.

Custer spent much of his boyhood living with his half-sister and his brother-in-law in Monroe Michigan, where he attended school and is now honored by a statue in the center of town. Before entering the United States Military Academy, he taught school in Ohio. A local legend suggests that Custer obtained his appointment to the Academy due to the influence of a prominent resident, who wished to keep Custer away from his daughter.

Custer graduated from West Point last of a class of 34 cadets, in 1861, just after the start of the Civil War. His tenure at the academy was a rocky one, and he came close to expulsion each of his four years due to excessive demerits, many from pulling pranks on fellow cadets. Nevertheless, in graduating he began a path to a distinguished war record, one that has been overshadowed in history by his role and fate in the Indian Wars.

Civil War

McClellan and Pleasonton

Custer was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry and immediately joined his regiment at the First Battle of Bull Run, where Army commander Winfield Scott detailed him to carry messages to Major General Irvin McDowell. After the battle he was reassigned to the 5th U.S. Cavalry, with which he served through the early days of the Peninsula Campaign in 1862. During the pursuit of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston up the Peninsula, on May 24, 1862, Custer persuaded a colonel into allowing him to lead an attack with four companies of Michigan infantry across the Chickahominy River above New Bridge. The attack was successful, capturing 50 Confederates. Major General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, termed it a "very gallant affair," congratulated Custer personally, and brought him onto his staff as an aide-de-camp with the temporary rank of captain.

When McClellan was relieved of command, Custer reverted to the rank of first lieutenant and returned to the 5th Cavalry for the Battle of Antietam and the Battle of Chancellorsville. Custer then fell into the orbit of Major General Alfred Pleasonton, commanding a cavalry division. The general introduced Custer to the world of extravagant uniforms and political maneuvering, and the young lieutenant became his protégé, serving on Pleasonton's staff while continuing his assignment with his regiment. Custer was quoted as saying that, "no father could love his son more than General Pleasonton loves me."

After Chancellorsville, Pleasonton became the commander of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac and his first assignment was to locate the army of Robert E. Lee, moving north through the Shenandoah Valley in the beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign. Custer distinguished himself by fearless, aggressive actions in some of the numerous cavalry engagements that started off the campaign, including Brandy Station and Aldie.

Brigade command and Gettysburg

Three days prior to the Battle of Gettysburg, General Meade promoted Custer from first lieutenant to brevet brigadier general (temporary rank) of volunteers. With no direct command experience, he became one of the youngest generals in the Union Army at age twenty-three. Custer lost no time in implanting his aggressive character on his brigade, part of the division of Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick. He fought against the Confederate cavalry of J.E.B. Stuart at Hanover and Hunterstown, on the way to the main event at Gettysburg.

Custer's style of battle sometimes bordered on reckless or foolhardy. He often impulsively gathered up whatever cavalrymen he could find in his vicinity and led them personally in bold assaults directly into enemy positions. One of his greatest attributes during the Civil War was luck, and he needed it to survive some of these charges. At Hunterstown, in an ill-considered charge ordered by Kilpatrick, Custer fell from his wounded horse directly before the enemy and became the target of numerous enemy rifles. He was rescued by the bugler of the 1st Michigan Cavalry, Norville Churchill, who galloped up, shot Custer's nearest assailant, and allowed Custer to mount behind him for a dash to safety.

Possibly Custer's finest hour in the Civil War came just east of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. In conjunction with Pickett's Charge to the west, Robert E. Lee dispatched Stuart's cavalry on a mission into the rear of the Union Army. Custer encountered the Union cavalry division of David McMurtrie Gregg, directly in the path of Stuart's horsemen. He convinced Gregg to allow him to stay and fight, while his own division was stationed to the south out of the action. Hours of charges and hand-to-hand combat ensued. Custer led a bold mounted charge of the 1st Michigan Cavalry, breaking the back of the Confederate assault and foiling Lee's plan. Considering the havoc that Stuart could have caused astride the Union lines of communication if he had succeeded, Custer was thus one of the unsung heroes of the battle of Gettysburg. Custer's brigade lost 257 men at Gettysburg, the highest loss of any Union cavalry brigade.

Marriage

He married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842‚Äď1933) on February 9, 1864. She was born in Monroe, Michigan, to Daniel Stanton Bacon and Eleanor Sophia Page. They had no children.

The Valley and Appomattox

When the cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac was reorganized under Philip Sheridan in 1864, Custer retained his command, and took part in the various actions of the cavalry in the Overland Campaign, including the Battle of the Wilderness (after which he was promoted to division command) and the Battle of Yellow Tavern, where "Jeb" Stuart was mortally wounded. At the Battle of Trevilian Station, however, Custer was humiliated by having his division trains overrun and his personal baggage captured by the Confederates.

When Confederate General Jubal A. Early moved down the Shenandoah Valley and threatened Washington, D.C., Custer's division was dispatched along with Sheridan to the Valley Campaigns of 1864. They pursued the Confederates at Winchester and effectively destroyed Early's army during Sheridan's counterattack at Cedar Creek.

Custer and Sheridan, having defeated Early, returned to the main Union Army lines at the Siege of Petersburg, where they spent the winter. In April 1865, the Confederate lines were finally broken and Robert E. Lee began his retreat to Appomattox Court House, pursued mercilessly by the Union cavalry. Custer distinguished himself by his actions at Waynesboro, Dinwiddie Court House, and Five Forks. His division blocked Lee's retreat on its final day and received the first flag of truce from the Confederate force.

Custer was present at the surrender at Appomattox Court House, and the table upon which the surrender was signed was presented to Custer as a gift for his gallantry. Before the close of the war, Custer received brevet promotions to brigadier and major general in the Regular Army and major general in the volunteers. As with most wartime promotions, these senior ranks were only temporary.

Indian Wars

In 1866, Custer was mustered out of the volunteer service, reduced to the rank of captain in the regular army. At the request of Maj. Gen. Phillip H. Sheridan, a bill was introduced into congress to promote Custer to major general, but the bill failed miserably. Custer was offered command of the 10th U.S. Cavalry (known as the Buffalo Soldiers) with the rank of full colonel, but turned the command down in favor of a lieutenant colonelcy of the 7th U.S. Cavalry and was assigned to that unit at Fort Riley, Kansas. His career suffered a setback in 1867 when he was court-martialed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for being absent without leave and suspended for one year. During this period Custer stayed with his wife at Fort Leavenworth, returning to the Army in 1868.

Custer took part in General Winfield Scott Hancock's expedition against the Cheyenne. Marching from Fort Supply, Indian Territory, he successfully attacked an encampment of Cheyennes and Arapahos (of 150 warriors and some fifty civilians and six white hostages)‚ÄĒthe Battle of Washita River‚ÄĒon November 27, 1868. This was regarded as the first substantial U.S. victory in the Indian Wars and a significant portion to the southern branch of the Cheyenne Nation was forced onto a U.S. appointed reservation as a result. Three white prisoners were freed during the encounter, and the others were killed by their Cheyenne captors. More than 120 Indian warriors were killed, along with less than 20 civilians. The deaths of these civilians, however, infuriated some in the East.

In 1873, Custer was sent to the Dakota Territory to protect a railroad survey party against the Sioux. On August 4, 1873, near the Tongue River, Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry clashed for the first time with the Sioux. Only one man on each side was killed.

In 1874, Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills and announced the discovery of gold on French Creek. Custer's announcement triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush and gave rise to the lawless town of Deadwood, South Dakota. In 1875, Custer swore by White Buffalo Calf Pipe, a pipe sacred to the Lakota, that he would not fight Native Americans again. Custer's peace gesture came at the time a U.S. Senate commission was meeting with Red Cloud and other Lakota chiefs to purchase access to the mining fields in the Black Hills. The tribe eventually turned down the government offer in favor of an 1868 treaty that promised U.S. military protection of their lands.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

In 1876, Custer's regiment was scheduled to mount an expedition against members of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations who resisted being confined to their designated reservations. However, troubles in Washington prevented his departure. The House Committee on Military Expenditures had commenced an investigation of Secretary of War William W. Belknap, and Custer was called to testify in the proceedings. His testimony, which he admitted to be only hearsay, seemed not to confirm the accusations against Belknap, but instead implicated President Ulysses S. Grant's brother Orville Grant. The president ordered Custer placed under arrest, relieved Custer of command, and ordered the expedition to proceed without him. Custer wrote to the president:

As my entire Regiment forms a part of the expedition and I am the senior officer of the regiment on duty in this department, I respectfully but most earnestly request that while not allowed to go in command of the expedition I may be permitted to serve with my regiment in the field. I appeal to you as a soldier to spare me the humiliation of seeing my regiment march to meet the enemy and I not share its dangers.

Grant relented and gave his permission for Custer to go. The 7th Cavalry departed from Fort Lincoln on May 17, 1876. Crow Indian scouts identified to Custer what they claimed was a large encampment of Native Americans. Following the common thinking of the time that Native Americans would flee if attacked by a strong force of cavalry, he decided to attack immediately. Some sources say that Custer, aware of his great popularity with the American public at the time, thought that he needed only one more victory over the Native Americans to get him nominated by the Democratic Party at the upcoming convention as their candidate for President of the United States (there was no primary system in 1876). This, together with his somewhat vainglorious ego, led him to foolhardy decisions in his last battle.

Custer knew he was outnumbered, though he did not know by how much (probably something on the order of three to one). Despite this, he split his forces into three battalions: one led by Major Marcus Reno, one by Captain Frederick Benteen, and one by himself. Captain Thomas M. McDougall and Company B, meanwhile were assigned to remain with the pack train. Reno was ordered to attack from south of the village, while Benteen was ordered to go west, scouting for any fleeing Native Americans, while Custer himself went north, in what was intended to be a classical pincer movement. But Reno failed in his actions, retreating after a timid charge with the loss of a quarter of his command. Meanwhile, Custer, having located the encampment, requested Benteen to come on for the second time. He sent the message: "Benteen, come on, big village, be quick, bring packs, bring packs!"

Benteen instead halted with Reno in a defensive position on the bluffs. All of the Native Americans that had been facing Reno were freed by Benteen's retreat, and now faced Custer. It is believed that at this point Custer attempted a diversionary attack on the flank of the village, deploying other companies on the ridges in order to give Benteen the time to join him. But Benteen never came, and so the company trying to ford the river was repulsed. Other groups of Native Americans made encircling attacks so that the cavalry companies on the hills collapsed and fell back together on what is now called "Custer Hill." There, the survivors of the command exchanged long-range fire with the Native Americans and fell to the last man.

The Native American assault was both merciless and tactically unusual. The Sioux Indians normally attacked in swift guerrilla raids, so perhaps Custer's early battle actions can be attributed to the fact he was certain they would retreat as they usually did. He was mistaken. As a result, there was only one survivor of Custer's force‚ÄĒCurley, a Crow scout who disguised himself as a Sioux soldier. Many of the corpses were mutilated, stripped, and had their skulls crushed. Lt. Edward Godfrey initially reported that Custer was not so molested. He had two bullet holes, one in the left temple and one in the breast.

Following the recovery of Custer's body, he was given a funeral with full military honors. He was buried on the battlefield, which was designated a National Cemetery in 1876, but was re-interred to the West Point Cemetery on October 10, 1877.

Controversial legacy

After his death, Custer achieved the lasting fame that eluded him in life. The public saw him as a tragic military hero and gentleman who sacrificed his life for his country. Custer's wife, Elizabeth, who accompanied him in many of his frontier expeditions, did much to advance this view with the publication of several books about her late husband: Boots and Saddles, Life with General Custer in Dakota (1885), Tenting on the Plains (1887), and Following the Guidon (1891). General Custer himself wrote about the Indian Wars in My Life on the Plains (1874). She was also the posthumous co-author of The Custer Story (1950).

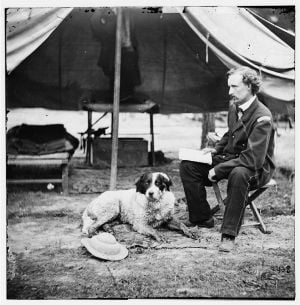

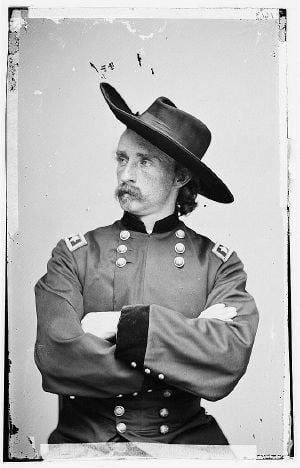

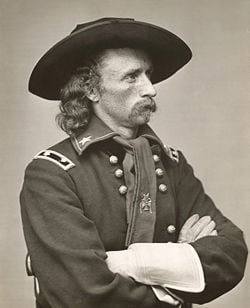

Within the culture of the U.S. Army, however, Custer was perceived as a self-seeking, glory-wanting man who placed his own needs above those of his own soldiers and the needs of the Army as a whole. He frequently invited correspondents to accompany him on his campaigns, and their favorable reportage contributed to his high reputation that lasted well into the twentieth century. It is believed that Custer was photographed more than any other Civil War officer.

Custer was fond of flamboyant dress; a witness described his appearance as "one of the funniest looking beings you ever saw ... like a circus rider gone mad." After being promoted to brigadier general, Custer sported a uniform that included shiny jackboots, tight olive corduroy trousers, a wide-brimmed slouch hat, tight hussar jacket of black velveteen with silver piping on the sleeves, a sailor shirt with silver stars on his collar, and a red cravat. He wore his hair in long glistening ringlets liberally sprinkled with cinnamon-scented hair oil.

The assessment of Custer's actions during the Indian Wars has undergone substantial reconsideration in modern times. For many critics, Custer was the personification and culmination of the U.S. Government's ill-treatment of the Native American tribes. Recent films and books including Little Big Man and Son of the Morning Star depict Custer as a cruel and murderous military commander whose actions today would warrant possible dismissal and court-martial.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Eicher, John H. and David J. Eicher (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Longacre, Edward G. (2000). Lincoln's Cavalrymen, A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-1049-1.

- Tagg, Larry (1998). The Generals of Gettysburg. Savas Publishing. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Utley, Robert M. (1964). Custer, cavalier in buckskin. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3347-3.

- Warner, Ezra J. (1964). Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

- Wert, Jeffry (1964). Custer, the controversial life of George Armstrong Custer. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83275-5.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. (2001). Glory Enough for All : Sheridan's Second Raid and the Battle of Trevilian Station. Brassey's Inc. ISBN 1-57488-353-4.

External links

All links retrieved April 18, 2024.

- Friends of the Little Bighorn Battlefield.

- Newson, T. M., "Custer's last fight with Sitting Bull". digital.library.wisc.edu.

- Victor, Frances Fuller, "Eleven years in the Rocky Mountains". digital.library.wisc.edu.

- Whittaker, Frederick, "A complete Life of Gen. George A. Custer". digital.library.wisc.edu.

- Finerty, John F., "The conquest of the Sioux, 1879". digital.library.wisc.edu.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.