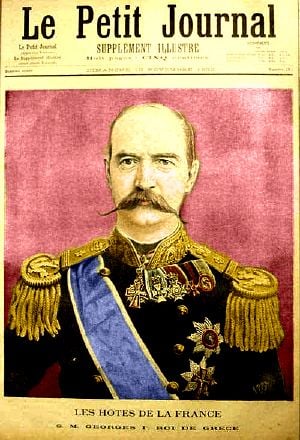

George I of Greece

| George I | ||

|---|---|---|

| King of the Hellenes | ||

| ||

| Reign | March 1863 – March 18, 1913 | |

| Born | December 24, 1845 | |

| Copenhagen, Denmark | ||

| Died | March 18, 1913 | |

| Thessaloniki[1] | ||

| Predecessor | Otto | |

| Successor | Constantine I | |

| Consort | Olga Konstantinovna of Russia | |

| Issue | Constantine I Prince George of Greece and Denmark Alexandra Georgievna of Greece | |

| Royal House | House of Glücksburg | |

| Father | Christian IX of Denmark | |

| Mother | Louise of Hesse | |

George I, King of the Hellenes Georgios A' Vasileus ton Ellinon; December 24, 1845 – March 18, 1913) was King of Greece from 1863 to 1913. Originally a Danish prince, when only 17 years old he was elected King by the Greek National Assembly, which had deposed the former King Otto. His nomination was both suggested and supported by the Great Powers (the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the Second French Empire and the Russian Empire). As the first monarch of the new Greek dynasty, his 50-year reign (the longest in modern Greek history) was characterized by territorial gains as Greece established its place in pre-World War I Europe and reunified much of the Greek speaking world. Two weeks short of the fiftieth anniversary of his accession, and during the First Balkan War, he was assassinated.

In contrast to George I, who ruled as a constitutional monarch, the reigns of his successors would prove short and insecure. George did much to bolster Greek pride and fostered a new sense of national identity. His successors, however, were less respectful towards the constitution, constantly interfering in Greek politics. Eventually, this interference led to the monarchy losing popular support and to its abolition, following a plebiscite, in 1974. Imposed from the outside, the monarchy was originally as much a tool of the Great Powers as it was a servant of the Greek people. Imposed system of governance cannot flourish unless they take deep root in the soil of the land. Despite George's best efforts, the Greek monarchy always remained "foreign."

Family and early life

George was born in Copenhagen, the second son of Prince Christian of Denmark and Louise of Hesse-Kassel.[2] Until his accession in Greece, he was known as Prince Vilhelm (William), the namesake of his paternal and maternal grandfathers,[3] Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, and Prince William of Hesse.

He was a younger brother of Frederick VIII of Denmark and Alexandra of Denmark, Queen consort of Edward VII of the United Kingdom. He was an older brother of Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark) (consort of Alexander III of Russia), Princess Thyra of Denmark (wife to Prince Ernest Augustus, 3rd Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale) and Prince Valdemar of Denmark.[2]

He began his career in the Royal Danish Navy, but when only 17 was elected King of the Hellenes on 18 March (Old Style March 30) following the deposition of King Otto. Paradoxically, he ascended a royal throne before his father,[4] who became King of Denmark on November 15 the same year.

Another candidate for the Crown

George was not the first choice of the Greek people. Upon the overthrow of Otto, the Greek people had rejected Otto's brother Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria, the heir presumptive, while still favoring the concept of a monarchy. Many Greeks, seeking closer ties to the pre-eminent world power, Great Britain, rallied around Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, second son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. British Foreign Minister Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, believed that the Greeks were "panting for increase in territory",[5] hoping for a gift of the Ionian Islands, which were then a British protectorate. The London Conference of 1832 prohibited any of the Great Powers' ruling families from accepting the crown, and in any event, Queen Victoria was adamantly opposed. The Greeks nevertheless insisted on holding a plebiscite in which over 95 percent of the 240,000 votes went for Prince Alfred.[6] There were 93 votes for a Republic and 6 for a Greek.[7] King Otto received one vote.[8]

Eventually, the Greeks and Great Powers narrowed their choice to Prince William of Denmark. There were two significant differences from the elevation of his predecessor: he was elected unanimously by the Greek Assembly, rather than imposed on the people by foreign powers, and he was proclaimed "King of the Hellenes" instead of "King of Greece".[9]

At his enthronement in Copenhagen, attended by a delegation of Greeks led by First Admiral and Prime Minister Constantine Kanaris, it was announced that the British government would cede the Ionian Islands to Greece in honor of the new monarch.[10]

Early reign (1863–1870)

The new seventeen-year-old king arrived in Athens on 18 October.[11] He was determined not to make the mistakes of his predecessor, so he quickly learned Greek in addition to his native Danish. He adopted the motto "My strength is the love of my people." The new king was seen frequently and informally in the streets of Athens, where his predecessor had only appeared in pomp. King George found the palace in a state of disarray after the hasty departure of King Otto and took to putting it right and updating the 40-year-old building. He also sought to ensure that he was not seen as too influenced by his Danish advisers, ultimately sending his uncle Prince Julius of Glücksburg back to Denmark with the words, "I will not allow any interference with the conduct of my government".[12]

Politically, the new king took steps to bring the protracted constitutional deliberations of the Assembly to conclusion. On October 19, 1864, he sent a demand, countersigned by Constantine Kanaris, to the Assembly explaining that he had accepted the crown on the understanding that a new constitution would be finalized, and that if it was not he would feel himself at "perfect liberty to adopt such measures as the disappointment of my hopes may suggest".[13] It was unclear from the wording whether he meant to return to Denmark or impose a constitution, but as either event was undesirable the Assembly soon came to an agreement.

On November 28, 1864, he took the oath to defend the new Constitution, which created a unicameral Assembly (Vouli) with representatives elected by direct, secret, universal male suffrage, a first in modern Europe. A constitutional monarchy was set up with George always deferring to the legitimate authority of the elected officials, while not unaware of the corruption present in elections and the difficulty of ruling a mostly illiterate population.[14] Between 1864 and 1910, there were 21 general elections and 70 different governments.[15]

Maintaining a strong relationship with his brother-in-law, Edward, Prince of Wales (eventually King Edward VII of the United Kingdom), King George sought his help in defusing the recurring issue of Crete, an overwhelmingly Greek island which remained under Ottoman Turk control. Since the reign of Otto, this desire to unite Greek lands in one nation had been a sore spot with the United Kingdom and France, which had embarrassed Otto by occupying the main port Piraeus to dissuade Greek irredentism during the Crimean War.[16] When the Cretans rose in rebellion in 1866, the Prince of Wales sought the support of Foreign Secretary Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby, in intervening in Crete on behalf of Greece.[17] Ultimately, the Great Powers did not intervene and the Ottomans put down the rebellion.[18]

Establishing a dynasty

During a trip to Russia to meet with his sister Maria Fyodorovna, consort to Alexander III of Russia, he met Olga Konstantinovna of Russia, a direct matrilineal descendant of the Greek Empress Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamatera. Olga was just 16 when she married George on October 27, 1867 (Gregorian calendar), in Saint Petersburg. They had eight children:

- Constantine I (1868–1923);

- George (1869–1957), High Commissioner of Crete;

- Alexandra (1870–1891), married Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia (son of Alexander II of Russia), mother of Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, assassin of Grigori Rasputin;

- Nicholas (1872–1938), father of Princess Olga of Greece and Denmark and Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent;

- Marie (1876–1940), married first Grand Duke George Mikhailovich of Russia (1863-1919) and second Admiral Perikles Ioannidis;

- Olga (1881), died aged three months;

- Andrew (1882–1944), father of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh; and

- Christopher (1888–1940), father of Prince Michael of Greece.

When alone with his wife, George usually conversed in German. Their children were taught English by their nannies, and when talking with his children he therefore spoke mainly English.[19] Intent on not letting his subjects know of his missing his native land, he discreetly maintained a dairy at his palace at Tatoi, which was managed by his former countrymen from Denmark as a bucolic reminder of his homeland.[20] Queen Olga was far less careful in her expression of apostasy from her native Russia, often visiting Russian ships at anchor in Piraeus two or three times before they weighed anchor.[21]

The king was related by marriage to the rulers of Great Britain, Russia and Prussia, maintaining a particularly strong attachment to the Prince and Princess of Wales, who visited Athens in 1869. Their visit occurred despite continued lawlessness which culminated in the murder of a party of British and Italian tourists, which comprised British diplomat Mr. E. H. C. Herbert (the first cousin of Henry Herbert, 4th Earl of Carnarvon), Mr. Frederick Vyner (the brother-in-law of George Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon, Lord President of the Council), Italian diplomat Count de Boyl, and Mr. Lloyd (an engineer).[22] George's relationships with the other ruling houses would assist the king and his small country but also often put them at the center of national political struggles in Europe.

Territorial expansion (1871–1881)

From 1864 to 1874, Greece had 21 governments, the longest of which lasted a year and a half.[23] In July 1874, Charilaos Trikoupis wrote an anonymous article in the newspaper Kairoi blaming King George and his advisers for the continuing political crisis caused by the lack of stable governments. In the article he accused the King of acting like an absolute monarch by imposing minority governments on the people. If the King insisted, he argued, that only a politician commanding a majority in the Vouli could be appointed Prime Minister, then politicians would be forced to work together more harmoniously in order to construct a coalition government. Such a plan, he wrote, would end the political instability and reduce the large number of smaller parties. Trikoupis admitted to writing the article after the supposed author was arrested, whereupon he himself was taken into custody. After a public outcry he was released and subsequently acquitted of the charge of "undermining the constitutional order." The following year the King asked Trikoupis to form a government (without a majority) and then read a speech from the throne declaring that in future the leader of the majority party in parliament would be appointed Prime Minister.[24]

Throughout the 1870s, Greece kept pressure on the Ottoman Empire, seeking territorial expansion into Epirus and Thessaly. The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 provided the first potential alliance for the Greek kingdom. George's sister Dagmar was the daughter-in-law of Alexander II of Russia, and she sought to have Greece join the war. The French and British refused to countenance such an act, and Greece remained neutral. At the Congress of Berlin convened in 1878 to determine peace terms for the Russo-Turkish War, Greece staked a claim to Crete, Epirus and Thessaly.[25]

The borders still were not finalized in June 1880 when a proposal very favorable to Greece which included Mount Olympus and Ioannina was offered by the British and French. When the Ottoman Turks strenuously objected, Prime Minister Trikoupis made the mistake of threatening a mobilization of the Hellenic Army. A coincident change of government in France, the resignation of Charles de Freycinet and replacement with Jules Ferry, led to disputes amongst the Great Powers and, despite British support for a more pro-Greek settlement, the Turks subsequently granted Greece all of Thessaly but only the part of Epirus around Arta. When the government of Trikoupis fell, the new Prime Minister, Alexandros Koumoundouros, reluctantly accepted the new boundaries.[26]

National progress (1882–1900)

While Trikoupis followed a policy of retrenchment within the established borders of the Greek state, having learned a valuable lesson about the vicissitudes of the Great Powers, his main opponents, the Nationalist Party led by Theodoros Deligiannis, sought to inflame the anti-Turkish feelings of the Greeks at every opportunity. The next opportunity arose when in 1885 Bulgarians rose in revolt of their Turkish overlords and declared themselves independent. Deligiannis rode to victory over Trikoupis in elections that year saying that if the Bulgarians could defy the Treaty of Berlin, so should the Greeks.[26]

Deligiannis mobilized the Hellenic Army, and the British Royal Navy blockaded Greece. The Admiral in charge of the blockade was Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, who had been the first choice of the Greeks to be their king in 1863,[26] and the First Lord of the Admiralty at the time was George Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon, whose brother-in-law had been murdered in Greece 16 years before.[27] This was not the last time that King George would discover that his family ties would not always be to his advantage. Deligiannis was forced to demobilize and Trikoupis regained the premiership. Between 1882 and 1897, Trikoupis and Deligiannis would alternate the premiership as their fortunes rose and fell.[28]

Greece in the last decades of the nineteenth century was increasingly prosperous and developing a sense of its role on the European stage. In 1893, the Corinth Canal was built by a French company cutting the sea journey from the Adriatic to Piraeus by 150 miles (241 km). In 1896, the Olympic Games were revived in Athens, and the Opening Ceremony of the 1896 Summer Olympics was presided over by the King. When Spiridon Louis, a shepherd from just outside Athens, ran into the Panathinaiko Stadium to win the Marathon event, the Crown Prince ran down onto the field to run the last thousand yards beside the Greek gold medalist, while the King stood and applauded.[29]

The popular desire to unite all Greeks within the territory of their kingdom (Megali Idea) was never far below the surface and another revolt against Turkish rule in Crete erupted again. In February 1897, King George sent his son, Prince George, to take possession of the island.[30][31] The Greeks refused an Ottoman offer of an autonomous administration, and Deligiannis mobilized for war.[32] The Great Powers refused the expansion of Greece, and on February 25, 1897 announced that Crete would be under an autonomous administration and ordered the Greek and Ottoman Turk militias to withdraw.[33]

The Turks agreed, but Prime Minister Deligiannis refused and dispatched 1400 troops to Crete under the command of Colonel Timoleon Vassos. Whilst the Great Powers announced a blockade, Greek troops crossed the Macedonian border and Abdul Hamid II declared war. The announcement that Greece was finally at war with the Turks was greeted by delirious displays of patriotism and spontaneous parades in honor of the King in Athens. Volunteers by the thousands streamed north to join the forces under the command of Crown Prince Constantine.

The war went badly for the ill-prepared Greeks; the only saving grace being the swiftness with which the Hellenic Army was overrun. By the end of April 1897, the war was lost. The worst consequences of defeat for the Greeks were mitigated by the intervention of the King's relatives in Britain and Russia; nevertheless, the Greeks were forced to give up Crete to international administration, and agree to minor territorial concessions in favor of the Turks and an indemnity of 4,000,000 Turkish pounds.[34]

The jubilation with which Greeks had hailed their king at the beginning of the war was reversed in defeat. For a time, he considered abdication. It was not until the King faced down an assassination attempt in February 1898 with great bravery that his subjects again held their monarch in high esteem.[35]

Later that year, after continued unrest in Crete, which included the murder of the British vice-consul,[36] Prince George of Greece was made the Governor-General of Crete under the suzerainty of the Sultan, after the proposal was put forward by the Great Powers. This effectively put Greece in day-to-day control of Crete for the first time in modern history.[37]

Later reign (1901–1913)

The death of Britain's Queen Victoria on January 22, 1901 left King George as the second-longest-reigning monarch in Europe.[38] His always cordial relations with his brother-in-law, the new King Edward VII, continued to tie Greece to Great Britain. This was abundantly important in Britain's support of the King's son George as Governor-General of Crete. Nevertheless, George resigned in 1906 after a leader in the Cretan Assembly, Eleftherios Venizelos, campaigned to have him removed.[39]

As a response to the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, Venizelos' power base was further strengthened, and on October 8, 1908 the Cretan Assembly passed a resolution in favor of union despite both the reservations of the Athens government under Georgios Theotokis[40] and the objections of the Great Powers.[41] The muted reaction of the Athens Government to the news from Crete led to an unsettled state of affairs on the mainland.

A group of military officers formed a military league, Stratiotikos Syndesmos, that demanded that the Royal family be stripped of their military commissions. To save the King the embarrassment of removing his sons from their commissions, they resigned them. The military league attempted a coup d'état called the Goudi Pronunciamento, and the King insisted on supporting the duly elected Hellenic Parliament in response. Eventually, the military league joined forces with Venizelos in calling for a National Assembly to revise the constitution. King George gave way, and new elections to the revising assembly were held. After some political maneuvering, Venizelos became Prime Minister of a minority government. Just a month later, Venizelos called new elections at which he won a colossal majority after most of the opposition parties declined to take part.[42]

Venizelos and the King were united in their belief that the nation required a strong army to repair the damage of the humiliating defeat of 1897. Crown Prince Constantine was reinstated as Inspector-General of the army,[43] and later Commander-in-Chief. Under his and Venizelos' close supervision the military was retrained and equipped with French and British help, and new ships were ordered for the Hellenic Navy. Meanwhile, through diplomatic means, Venizelos had united the Christian countries of the Balkans in opposition to the ailing Ottoman Empire.[44]

When Montenegro declared war on Turkey on October 8, 1912, it was joined quickly, after ultimata, by Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece in what is known as the First Balkan War. The results of this campaign differed radically from the Greek experience at the hands of the Turks in 1897. The well-trained Greek forces, 200,000 strong, won victory after victory. On November 9, 1912, Greek forces rode into Salonika, just a few hours ahead of a Bulgarian division. Followed by the Crown Prince and Venizelos in a parade a few days later, King George rode in triumph through the streets of the second-largest Greek city.[45]

Just as he did in Athens, the King went about Salonika without any meaningful protection force. While out on an afternoon walk near the White Tower of Thessaloniki on March 18, 1913, he was shot at close range in the back by Alexandros Schinas, who was "said to belong to a Socialist organization" and "declared when arrested that he had killed the King because he refused to give him money".[46] The Greek government denied any political motive for the assassination, saying that Schinas was an alcoholic vagrant.[47] Schinas was tortured in prison[48] and six weeks later fell to his death from a police station window.[49]

For five days the coffin of the King, draped in the Danish and Greek flags, lay in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens before his body was committed to the tomb at his palace in Tatoi. Unlike his father, the new King Constantine was to prove less willing to accept the advice of ministers, or that of the three protecting powers (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the French Third Republic and the Russian Empire).

Legacy

George I established a dynasty that reigned in Greece until 1967. Unlike his predecessor, Otto of Greece, he respected the Constitution. He is generally recognized, despite some criticism, to have reigned as a successful constitutional monarch. Nash describes him as the only successful monarch of the House he himself established.[50] Territorial gains during his long reign did much to bolster Greek self-confidence and pride as heirs of Ancient Greece's civilization and culture, of which the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896 was symbolic. This territorial expansion was very much in tune with the aspirations of the people of Greece, who wanted to see the "unification under the political sovereignty of the national state … all the territories in the Eastern Mediterranean region where Greek-speaking inhabitants predominate."[51]

Unfortunately, his successors' reigns were shorter. Democracy, too, remained fragile in the land of its birth which continued to witness a struggle between autocracy and democracy for much of the twentieth century. For years, dictatorships and military rule would hinder the development of a healthy democracy. A new state needed a clear vision of how it was to be governed, so that good practice could become the established pattern of political life and leadership.

Otto, the first King of the modern nation state of Greece, had been unable to provide this, failing to lay down a solid foundation on which others could build. On the one hand, George I did adhere to democratic principles, unlike Otto. Yet his successors emulated Otto more than George. When the monarchy was officially abolished by a "plebiscite … universally acknowledged to be fair and free from coercion" in 1974, it was voted out in the main because too many Kings had interfered in politics.[52] The monarchy had been imposed from outside and at least until the end of World War I it was always as much a tool of the Great Powers as it was a servant of the Greek people. No imposed system of governance can flourish, unless it takes deep roots in the soil of the land. Despite George's best efforts, the Greek monarchy always remained "foreign."

Ancestors

| 8. Friedrich Karl Ludwig, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Beck | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg | ||||||||||||||||

| 9. Countess Friederike of Schlieben | ||||||||||||||||

| Princess Louise Caroline of Hesse-Kassel | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Charles of Hesse | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Louise Caroline of Hesse-Kassel | ||||||||||||||||

| 11. Luise, Princess of Denmark and Norway]] | ||||||||||||||||

| Frederick William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. Prince Frederick of Hesse | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Prince William of Hesse | ||||||||||||||||

| 13. Princess Caroline of Nassau-Usingen | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Louise of Hesse-Kassel | ||||||||||||||||

| 14. Frederick, Hereditary Prince of Denmark and Norway | ||||||||||||||||

| 7. Princess Louise Charlotte of Denmark]] | ||||||||||||||||

| 15. Sophia Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin | ||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ At the time of the King's assassination, Thessaloniki was in occupied Ottoman territory. The city was recognized as part of Greece by the Treaty of Bucharest (1913) five months later.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John Van der Kiste. Kings of the Hellenes: the Greek kings, 1863-1974. (Dover, NH: Alan Sutton, 1994), 6.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 6–8.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 1994, 6–11.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 1994, 4

- ↑ Richard Clogg. A short history of modern Greece. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 82

- ↑ E.S. Forster and Douglas Dakin. A short history of modern Greece, 1821-1956. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977), 17

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 1994, 5.

- ↑ C.M. Woodhouse. A short history of modern Greece. (New York, NY: Praeger, 1968), 170.

- ↑ The Times (London), June 8, 1863, 12. col. C.

- ↑ Forster and Dakin, 18.

- ↑ The Times (London), February 14, 1865, 10. col. C.

- ↑ Royal Message to the National Assembly, 6 October 1864 quoted in The Times (London) Monday, October 31, 1864, 9. col. E.

- ↑ John Kennedy Campbell and Philip Sherrard. 1968. Modern Greece. (London, UK: Benn, 1968), 99.

- ↑ Woodhouse, 172.

- ↑ Woodhouse, 167.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 1994, 23.

- ↑ Clogg, 87.

- ↑ Forster and Dakin, 74.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 37.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 39.

- ↑ "The King of the Hellenes to the Prince of Wales, April 1870." in Queen Victoria, George Earle Buckle, (ed.) Letters of Queen Victoria 1870–1878, vol II. (London, UK: John Murray, 1926), 16.

- ↑ The ministry of Epameinontas Deligeorgis, (July 20, 1872 – February 21, 1874)

- ↑ Clogg, 86

- ↑ Clogg, 89.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Woodhouse, 181.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 35.

- ↑ Clogg, 90–92.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 54–55.

- ↑ Woodhouse, 182.

- ↑ The Times (London) February 12, 1897, 9. col. E.

- ↑ Clogg, 93.

- ↑ The Times (London) February 25, 1897, 5. col. A.

- ↑ Clogg, 94.

- ↑ The Times (London) February 28, 1898, 7. col. A.

- ↑ Forster and Dakin, 33.

- ↑ Woodhouse, 182.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, 63.

- ↑ Woodhouse, 186.

- ↑ Campbell and Sherrard, 1968, 109–110.

- ↑ Forster and Dakin, 44.

- ↑ Clogg, 97–99.

- ↑ Clogg, 100.

- ↑ Clogg, 101–102.

- ↑ The Times (London) November 26, 1912, 11, col. C.

- ↑ The Times (London) March 18, 1913, 6.

- ↑ The Times (London) March 20, 1913, 6.

- ↑ The New York Times March 20, 1913, 3.

- ↑ The New York Times May 7, 1913, 3.

- ↑ Michael Nash, The Greek Monarchy in retrospect. Contemporary Review (Sept. 1994): 2. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- ↑ Cyril E. Black, "The Greek Crisis: Its Constitutional Background." The Review of Politics 10(1)(1948):84-99. 84.

- ↑ Allison and Nicolaïdis, 1997, 24.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allison, Graham T., and Kalypso Nicolaïdis. The Greek paradox: promise vs. performance. (CSIA studies in international security.) Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0262510929.

- Black, Cyril E. "The Greek Crisis: Its Constitutional Background." The Review of Politics 10(1) (1948):84-99.

- Campbell, John K., and Philip Sherrard. Modern Greece. (Nations of the modern world.) London, UK: Benn, 1968. ISBN 978-0510379513.

- Clogg, Richard. A short history of modern Greece. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0521295178.

- Forster, E.S., and Douglas Dakin. A short history of modern Greece, 1821-1956. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0837198033.

- Tantzos, G. Nicholas. King by chance: a biographical novel of King George I of Greece, 1863-1913. New York, NY: Atlantic International Publications, 1988. ISBN 978-0938311027.

- Van der Kiste. Sutton Pub Ltd., 1994. ISBN 978-0750905251.

- Queen Victoria. George Earle Buckle, (ed.). Letters of Queen Victoria 1870–1878, vol II. London, UK: John Murray, 1926.

- Woodhouse, C.M. A short history of modern Greece. New York, NY: Praeger, 1968.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.