Gothic fiction

Gothic fiction began in the United Kingdom with The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole. It depended for its effect on the pleasing terror it induced in the reader, a new extension of literary pleasures that was essentially Romantic. It is the predecessor of modern horror fiction and, above all, has led to the common definition of "gothic" as being connected to the dark and horrific.

Prominent features of gothic fiction include terror (psychological as well as physical), mystery, the supernatural, ghosts, haunted houses and Gothic architecture, castles, darkness, death, decay, “doubles,” madness (especially mad women), secrets, hereditary curses, and persecuted maidens.

Important ideas concerning and influencing the Gothic include: Anti-Catholicism, especially criticism of Catholic excesses such as the Inquisition (in southern European countries such as Italy and Spain); romanticism of an ancient Medieval past; melodrama; and parody (including self-parody).

Origins of the Gothic

The term "gothic" was originally a disparaging term applied to a style of medieval architecture (Gothic architecture) and art (Gothic art). The opprobrious term "gothick" was embraced by the eighteenth-century proponents of the gothic revival, a forerunner of the Romantic genres. Gothic revival architecture, which became popular in the nineteenth century, was a reaction to the classical architecture that was a hallmark of the Age of Reason.

In a way similar to the gothic revivalists' rejection of the clarity and rationalism of the neoclassical style of the Enlightened Establishment, the term "gothic" became linked with an appreciation of the joys of extreme emotion, the thrill of fearfulness and awe inherent in the sublime, and a quest for atmosphere. The ruins of gothic buildings gave rise to multiple linked emotions by representing the inevitable decay and collapse of human creations—thus the urge to add fake ruins as eye catchers in English landscape parks. English Protestants often associated medieval buildings with what they saw as a dark and terrifying period, characterized by harsh laws enforced by torture, and with mysterious, fantastic and superstitious rituals.

The first gothic romances

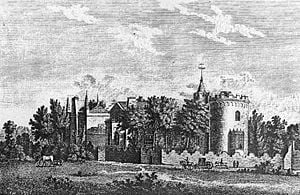

The term "gothic" came to be applied to the literary genre precisely because the genre dealt with such emotional extremes and dark themes, and because it found its most natural settings in the buildings of this style—castles, mansions, and monasteries, often remote, crumbling, and ruined. It was a fascination with this architecture and its related art, poetry (see Graveyard Poets), and even landscape gardening that inspired the first wave of gothic novelists. For example, Horace Walpole, whose The Castle of Otranto is often regarded as the first true gothic romance, was obsessed with fake medieval gothic architecture, and built his own house, Strawberry Hill, in that form, sparking a gothic revival fashion.

Walpole's novel arose out of this obsession with the medieval. He originally claimed that the book was a real medieval romance he had discovered and republished. Thus was born the gothic novel's association with fake documentation to increase its effect. Indeed, The Castle of Otranto was originally subtitled "A Romance"—a literary form held by educated taste to be tawdry and unfit even for children, due to its superstitious elements—but Walpole revived some of the elements of the medieval romance in a new form. The basic plot created many other gothic staples, including a threatening mystery and an ancestral curse, as well as countless trappings such as hidden passages and oft-fainting heroines.

It was Ann Radcliffe who created the gothic novel in its now-standard form. Among other elements, Radcliffe introduced the brooding figure of the gothic villain, which later developed into the Byronic hero. Unlike Walpole, her novels, beginning with The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), were best-sellers—virtually everyone in English society was reading them.

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid. I have read all Mrs. Radcliffe's works, and most of them with great pleasure. The Mysteries of Udolpho, when I had once begun it, I could not lay down again; I remember finishing it in two days – my hair standing on end the whole time." [said Henry]

...

"I am very glad to hear it indeed, and now I shall never be ashamed of liking Udolpho myself." [replied Catharine]

—Jane Austen Northanger Abbey (written 1798)

France and Germany

At about the same time, parallel Romantic literary movements developed in continental Europe: the roman noir ("black novel") in France and the Schauerroman ("shudder novel") in Germany.

Writers of the roman noir include François Guillaume Ducray-Duminil, Baculard d'Arnaud, and Stéphanie Félicité Ducrest de St-Albin, comtesse de Genlis.

The German Schauerroman was often more horrific and violent than the English gothic novel, and influenced Matthew Gregory Lewis's The Monk (1796) in this regard (as the author himself declared). Lewis's novel, however, is often read as a sly, tongue-in-cheek spoof of the emerging genre. On the other hand, some critics also interpret this novel as key text, representative of a gothic that does not end up in (or give in to) subtleties and domesticity, as did the work of Radcliffe, Roche, Parsons and Sleath, for example.

The ecclesiastical excesses portrayed in Lewis's shocking tale may have influenced established terror-writer Radcliffe in her last and finest novel The Italian (1797). One of Radcliffe's contemporaries is said to have suggested that if she wished to transcend the horror of the Inquisition scenes in this book she would have to visit hell itself (Birkhead 1921).

Some writings of the Marquis de Sade have also been called "gothic" though the marquis himself never thought of his work as such. Sade provided a critique of the genre in his the preface of his Reflections on the Novel (1800) that is still widely accepted today, arguing that the gothic is "the inevitable product of the revolutionary shock with which the whole of Europe resounded.” This correlation between the French Revolutionary “Terror” and the 'terrorist school' of writing represented by Radcliffe and Lewis was noted by contemporary critics of the genre.

One notable later writer in the continental tradition was E. T. A. Hoffmann.

Gothic Parody

The excesses and frequent absurdities of the traditional Gothic made it rich territory for satire. The most famous parody of the Gothic is Jane Austen's novel Northanger Abbey (1818) in which the naive protagonist, after reading too much Gothic fiction, conceives herself a heroine of a Radcliffian romance and imagines murder and villainy on every side, though the truth turns out to be somewhat more prosaic. Jane Austen's novel is valuable for including a list of early Gothic works since known as the Northanger Horrid Novels:

- The Necromancer: or, The Tale of the Black Forest (1794) by 'Ludwig Flammenberg' (pseudonym for Carl Friedrich Kahlert; translated by Peter Teuthold)

- Horrid Mysteries (1796) by the Marquis de Grosse (translated by P. Will)

- Castle of Wolfenbach (1793) by Eliza Parsons

- The Mysterious Warning, a German Tale (1796) by Eliza Parsons

- Clermont (1798) by Regina Maria Roche

- Orphan of the Rhine (1798) by Eleanor Sleath

- The Midnight Bell (1798) by Francis Lathom

These books, with their lurid titles, were once thought to be the creations of Jane Austen's imagination, though later research confirmed that they did actually exist and stimulated renewed interest in the Gothic.

The Romantics

The Romantic poets were heir to the Gothic tradition, using elements of terror in the production of the sublime. Prominent examples include Coleridge's Christabel and Keats' La Belle Dame sans Merci: A Ballad which both feature fey lady vampires. In prose the celebrated ghost-story competition between Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley and John William Polidori at the Villa Diodati on the banks of Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816 produced both Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) and Polidori's The Vampyre (1819). This latter work is considered by many as one of the most influential works of fiction ever written and spawned a craze for vampire fiction, vampire plays and later vampire films, which remains popular even today. Mary Shelley's novel, though clearly influenced by the gothic tradition, is often considered the first science fiction novel.

Victorian Gothic

Though it is sometimes asserted that the Gothic had played itself out by the Victorian era—declining into the cheap horror fiction of the "penny dreadful" type, which retailed the strange surprising adventures of such as Varney the Vampire—in many ways Gothic was now entering its most creative phase, even if it was no longer the dominant literary genre.

Gothic works of this period include the macabre, necrophiliac work of Edgar Allen Poe. His Fall of the House of Usher (1839) revisited classic Gothic tropes of aristocratic decay, death, and madness, while the legendary villainy of the Spanish Inquisition, previously explored by Radcliffe, Lewis and Maturin, made an unexpected comeback in his The Pit and the Pendulum.

Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847) transported the Gothic to the forbidding Yorkshire Moors, giving us ghostly apparitions and a Byronic anti-hero in the person of the demonic Heathcliff.

Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847) contains many of the trappings of gothic fiction, introducing the motif of “The Madwoman in the Attic.”

The gloomy villain, forbidding mansion and persecuted heroine of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu's Uncle Silas (1864) shows the direct influence of both Walpole's Otranto and Radcliffe's Udolpho and Le Fanu's short story collection. In a Glass Darkly (1872) includes the superlative vampire tale Carmilla which provided fresh blood for that particular strand of the Gothic, providing inspiration for Bram Stoker's Dracula.

The genre was also a heavy influence on more mainstream writers, such as Charles Dickens, who read gothic novels as a teenager and incorporated their gloomy atmosphere and melodrama into his own works, shifting them to a more modern period and an urban setting. The mood and themes of the gothic novel held a particular fascination for the Victorians, with their morbid obsession with mourning rituals, Mementos, and mortality in general.

Post-Victorian legacy

By the 1880s, it was time for a revival of the Gothic as a semi-respectable literary form. This was the period of the gothic works of Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Machen, and Oscar Wilde, and the most famous gothic villain ever appeared in Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897).

Daphne du Maurier's novel Rebecca (1938) is in many ways a reworking of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre. Jean Rhys's 1966 novel, Wide Sargasso Sea again took Brontë's story, this time explicitly reworking it by changing the narrative point of view to one of the minor characters, a now popular but then innovative post-modern technique. The Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar's extensive feminist critique of Victorian era literature, takes its title from Jane Eyre.

Other notable writers included Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson, and H. P. Lovecraft. Lovecraft's protégé, Robert Bloch, penned the gothic horror classic, Psycho, which drew on the classic interests of the genre. From these, the gothic genre per se gave way to modern horror fiction, although many literary critics use the term to cover the entire genre, and many modern writers of horror (or indeed other types of fiction) exhibit considerable gothic sensibilities—examples include the works of Anne Rice, as well as some of the less sensationalist works of Stephen King.

The genre also influenced American writing to create the genre of Southern Gothic literature, which combines some Gothic sensibilities (such as the grotesque) with the setting and style of the Southern United States. Examples include William Faulkner, Harper Lee, and Flannery O'Connor.

The themes of the Gothic have had innumerable children. It led to the modern horror film, one of the most popular of all genres seen in films. While few classical composers drew on gothic works, twentieth century popular music drew on it strongly, eventually resulting in ‘gothic rock’ and the ‘goth’ subculture surrounding it. Themes from gothic writers such as H. P. Lovecraft were also used amongst heavy metal bands.

Prominent examples

- The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- Vathek, an Arabian Tale (1786) by William Thomas Beckford (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) by Ann Radcliffe (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- Caleb Williams (1794) by William Godwin (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Monk (1796) by Matthew Gregory Lewis (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Italian (1797) by Ann Radcliffe

- Clermont (1798) by Regina Maria Roche

- Wieland (1798) by Charles Brockden Brown

- The Children of the Abbey (1800) by Regina Maria Roche

- Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley (Full text at Wikisource)

- The Vampyre; a Tale (1819) by John William Polidori (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) by Charles Robert Maturin

- Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821) by Thomas de Quincey (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824) by James Hogg (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827) by Jane Webb Loudon

- Young Goodman Brown (1835) by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- The Minister's Black Veil (1836) by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- The Fall of the House of Usher (1839) by Edgar Allan Poe (Full text at Wikisource)

- The Tell-Tale Heart (1843) by Edgar Allan Poe (Full text at Wikisource)

- The Quaker City; or, the Monks of Monk Hall (1844) by George Lippard (full text page images at openlibrary.org - USA best-seller)

- The Mummy's Foot (1863) by Théophile Gautier (Full text at Wikisource)

- Carmilla (1872) by Joseph Sheridan le Fanu (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) by Robert Louis Stevenson (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) by Oscar Wilde (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Horla (1887) by Guy de Maupassant (Full text at Wikisource)

- The Yellow Wallpaper (1892) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker (Full text at Wikisource)

- The Turn of the Screw (1898) by Henry James (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Monkey's Paw (1902 by W.W. Jacobs (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Phantom of the Opera (1910) by Gaston Leroux (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Lair of the White Worm (1911) by Bram Stoker (Full text at Wikisource)

- Gormenghast (1946 - 1959) by Mervyn Peake

- The Haunting of Hill House (1959) by Shirley Jackson

Gothic satire

- Northanger Abbey (1818) by Jane Austen (Full text at Wikisource)

- Nightmare Abbey (1818) by Thomas Love Peacock (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Ingoldsby Legends (1840) by Thomas Ingoldsby (Full text at The Ex-Classics Website)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Birkhead, Edith. 1921. The Tale of Terror. Reprint edition, 2006. Aegypan. ISBN 1598180118

- Mighall, Robert. 1999. A Geography of Victorian Gothic Fiction: Mapping History's Nightmares. New edition, 2003. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199262187

- Punter, David. 1996. The Literature of Terror (2 vols). Longman Publishing Group. Vol. 1: ISBN 0582237149; Vol. 2: ISBN 0582290554

- Stevens, David. 2000. The Gothic Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521777321

- Sullivan, Jack (ed.). 1986. The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural. New York: Viking. ISBN 0670809020

- Summers, Montague. 1938. Gothic Quest. New York: Gordon Press Publishers. ISBN 0849002540

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.