| Feminism |

|

Concepts History Suffrage Waves of Feminism Subtypes Amazon By country or region France Lists |

Feminism comprises a number of social, cultural and political movements, theories and moral philosophies concerned with gender inequalities and equal rights for women. The term “feminism” originated from the French word “feminisme,” coined by the utopian socialist Charles Fourier, and was first used in English in the 1890s, in association with the movement for equal political and legal rights for women. Feminism takes a number of forms in a variety of disciplines such as feminist geography, feminist history and feminist literary criticism. Feminism has changed aspects of Western society. Feminist political activists have been concerned with issues such as individual autonomy, political rights, social freedom, economic independence, abortion and reproductive rights, divorce, workplace rights (including maternity leave and equal pay), and education; and putting an end to domestic violence, gender stereotypes, discrimination, sexism, objectification, and prostitution.

Historians of feminism have identified three “waves” of feminist thought and activity.[1] The first wave, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, focused primarily on gaining legal rights, political power and suffrage for women. The second, in the 1960s and 1970s, encouraged women to understand aspects of their own personal lives as deeply politicized, and was largely concerned with other issues of equality, such as the end to discrimination in society, in education and in the work place. The third arose in the early 1990s as a response to perceived failures of the second-wave, and a response to the backlash against initiatives and movements created by the second-wave. Throughout most of its history, most leaders of feminist social and political movements, and feminist theorists, have been middle-class white women, predominantly in Britain, France and the US. At least since Sojourner Truth's 1851 speech to US feminists, however, women of other races have proposed alternative feminisms, and women in former European colonies and the Third World have proposed alternative "post-colonial" and "Third World" feminisms.

History of Feminism

Feminism comprises a number of social, cultural and political movements, theories and moral philosophies concerned with gender inequalities and equal rights for women. In its narrowest interpretation, it refers to the effort to ensure legal and political equality for women; in its broadest sense it comprises any theory which is grounded on the belief that women are oppressed or disadvantaged by comparison with men, and that their oppression is in some way illegitimate or unjustified.

The term “feminism” originated from the French word “feminisme,” coined by the utopian socialist Charles Fourier, and was first used in English in the 1890s, in association with the movement for equal political and legal rights for women.[2] There is some debate as to whether the term “feminism” can be appropriately applied to the thought and activities of earlier women (and men) who explored and challenged the traditional roles of women in society.

Contemporary feminist historians distinguish three “waves” in the history of feminism. The first-wave refers to the feminism movement of the nineteenth through early twentieth centuries, which dealt mainly with the Suffrage movement. The second-wave (1960s-1980s) dealt with the inequality of laws, as well as cultural inequalities. The third-wave of Feminism (1990s-present), is seen as both a continuation of and a response to the perceived failures of the second-wave.[3]

First-wave feminism

First-wave feminism refers to a period of feminist activity during the nineteenth century and early twentieth century in the United Kingdom and the United States. Originally it focused on equal legal rights of contract and property, and opposition to chattel marriage and ownership of married women (and their children) by husbands. A Vindication of the Rights of Women, written by Mary Wollstonecraft in 1742, is considered a germinal essay of feminism. Wollstonecraft protested against the stereotyping of women in domestic roles, the failure to regard women as individuals in their own right, and the failure to educate girls and women to use their intellect.

By the end of the nineteenth century, activism focused primarily on gaining political power and women's suffrage, though feminists like Voltairine de Cleyre (1866 – 1912) and Margaret Sanger (1879 – 1966) were active in campaigning for women's sexual, reproductive and economic rights. In Britain the Suffragettes campaigned for the women's vote. In 1918 the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed, granting the vote to women over the age of 30 who owned houses. In 1928 this was extended to all women over eighteen.[4]

In the United States leaders of this movement include Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who each campaigned for the abolition of slavery prior to championing women's right to vote. Other important leaders included Lucy Stone, Olympia Brown, and Helen Pitts. American first-wave feminism involved women from a wide range of backgrounds, some belonging to conservative Christian groups (such as Frances Willard and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union), others representing the diversity and radicalism of much of second-wave feminism (such as Stanton, Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage and the National Woman Suffrage Association, of which Stanton was president).

In the United States first-wave feminism is considered to have ended with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1919), granting women the right to vote.[5]

Second-wave feminism

“Second-wave feminism” refers to a period of feminist activity beginning in the early 1960s and lasting through the late 1980s. It was a continuation of the earlier phase of feminism which sought legal and political rights in the United Kingdom and the United States.[6] Second-wave feminism has existed continuously since then, and coexists with what is termed “third-wave feminism.” Second-wave feminism saw cultural and political inequalities as inextricably linked. The movement encouraged women to understand aspects of their own personal lives as deeply politicized, and reflective of a gender-biased structure of power. While first-wave feminism focused upon absolute rights such as suffrage, second-wave feminism was largely concerned with other issues of equality, such as the end to gender discrimination in society, in education and in the workplace. The title of an essay by Carol Hanisch, "The Personal is Political," became a slogan synonymous with second-wave feminism and the women's liberation movement.[7]

Women's liberation in the USA

The term “Women’s Liberation” was first used in 1964 and first appeared in print in 1966.[8] By 1968, although the term “Women’s Liberation Front” appeared in “Ramparts,” the term “women’s liberation” was being used to refer to the whole women’s movement.[9] Although no burning took place, a number of feminine products including bras were thrown into a "Freedom Trash Can," the term "bra-burning" became associated with the movement.[10]

The Feminine Mystique, published in 1963 by Betty Friedan, criticized the idea that women could only find fulfillment through childbearing and homemaking. According to Friedan's obituary in the The New York Times The Feminine Mystique “ignited the contemporary women's movement in 1963 and as a result permanently transformed the social fabric of the United States and countries around the world” and “is widely regarded as one of the most influential nonfiction books of the 20th century.”[11] Friedan hypothesized that women are victims of a false belief system that requires them to find identity and meaning in their lives through their husbands and children. Such a system causes women to completely lose their identity in that of their family. Friedan specifically located this system among post-World War II middle-class suburban communities. She pointed out that though America's post-war economic boom had led to the development of new technologies that were supposed to make household work less difficult, they often had the result of making women's work less meaningful and valuable. She also critiqued Freud's theory that women were envious of men. Friedan’s book played an important role in encouraging women to question traditional female roles and seek self-fulfillment.[12]

Third-wave feminism

Third-wave feminism has its origins in the mid 1980s, with feminist leaders rooted in the second-wave like Gloria Anzaldua, bell hooks, Chela Sandoval, Cherrie Moraga, Audre Lorde, Maxine Hong Kingston, and other black feminists, who sought to negotiate prominent space within feminist thought for consideration of race-related subjectivities.[13]

The third-wave of feminism arose in the early 1990s as a response to perceived failures of the second-wave, and a response to the backlash against initiatives and movements created by the second-wave. Third-wave feminism seeks to challenge or avoid what it deems the second-wave's "essentialist" definitions of femininity, claiming that these definitions over-emphasized the experiences of upper middle class white women and largely ignored the circumstances of lower-class women, minorities and women living in other cultures. A post-structuralist interpretation of gender and sexuality is central to much of the third-wave's ideology. Third-wave feminists often focus on "micropolitics," and challenge the second-wave's paradigm as to what is, or is not, good for females.[14]

In 1991, Anita Hill accused Clarence Thomas, a man nominated to the United States Supreme Court, of sexual harassment. Thomas denied the accusations and after extensive debate, the US Senate voted 52-48 in favor of Thomas.[13] In response to this case, Rebecca Walker published an article entitled "Becoming the Third Wave" in which she stated, "I am not a post-feminism feminist. I am the third-wave."[1]

Contemporary feminism

Contemporary feminism comprises a number of different philosophical strands. These movements sometimes disagree about current issues and how to confront them. One side of the spectrum includes a number of radical feminists, such as Mary Daly, who argue that society would benefit if there were dramatically fewer men.[15] Other figures such as Christina Hoff Sommers and Camille Paglia identify themselves as feminist but accuse the movement of anti-male prejudice.[16]

Some feminists, like Katha Pollitt, author of Reasonable Creatures, or Nadine Strossen, consider feminism to hold simply that "women are people." Views that separate the sexes rather than unite them are considered by these writers to be sexist rather than feminist.[17] There are also debates between difference feminists such as Carol Gilligan, who believe that there are important differences between the sexes, which may or may not be inherent, but which cannot be ignored; and those who believe that there are no essential differences between the sexes, and that their societal roles are due to conditioning.[18] Individualist feminists such as Wendy McElroy are concerned with equality of rights, and criticize sexist/classist forms of feminism as "gender feminism."

French feminism

Feminism in France originated during the French Revolution, with the organization of several associations such as the Société fraternelle de l'un et l'autre sexe (Fraternal Society of one and the other Sex), the Société des républicaines révolutionnaires (Society of Revolutionary Republicans—the final "e" implicitly referring to Republican Women), which boasted 200 exclusively female members. The feminist movement developed itself again in Socialist movements of the Romantic generation, in particular among Parisian Saint-Simonians. Women freely adopted new life-styles, often arousing public indignation. They claimed equality of rights and participated in the production of an abundant literature exploring freedom for women. Charles Fourier's Utopian Socialist theory of passions advocated "free love," and his architectural model of the phalanstère community explicitly took into account women's emancipation. A few famous figures emerged during the 1871 Paris Commune, including Louise Michel, Russian-born Elisabeth Dmitrieff, Nathalie Lemel and Renée Vivien.

Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir, a French author and philosopher who wrote on philosophy, politics, and social issues, published a treatise in 1949, The Second Sex, a detailed analysis of women's oppression and a foundational tract of contemporary feminism. It set out a feminist existentialism which prescribed a moral revolution. As an existentialist, de Beauvoir accepted the precept that "existence precedes essence"; hence "one is not born a woman, but becomes one." Her analysis focused on the social construction of Woman as the quintessential “Other” as fundamental to women's oppression.[19] She argued that women have historically been considered deviant and abnormal, and that even Mary Wollstonecraft had considered men to be the ideal toward which women should aspire. According to Beauvoir, this attitude had limited women's success by maintaining the perception that they are a deviation from the normal, and are outsiders attempting to emulate "normality." [19]

1970s until the present

French feminists have a tendency to attack the rationalist Enlightenment thinking which first accorded them intellectual freedom as being itself male-oriented, and approach feminism with the concept of écriture féminine (female, or feminine, writing). Helene Cixous argues that traditional writing and philosophy are 'phallocentric,' and along with other French feminists such as Luce Irigaray, emphasizes "writing from the body" as a subversive exercise.[20] Another theorist working in France (but originally from Bulgaria) is Julia Kristeva, whose work on the semiotic and abjection has influenced feminist criticism. However, according to Elizabeth Wright, "none of these French feminists align themselves with the feminist movement as it appeared in the Anglophone world."[20]

Indian feminism

With the rise of a new wave of feminism across the world, a new generation of Indian feminists emerged. Increasing numbers of highly-educated and professional Indian women have entered the public arena in fields such as politics, business and scientific research. Contemporary Indian feminists are fighting for individual autonomy, political rights, social freedom, economic independence, tolerance, co-operation, nonviolence and diversity, abortion and reproductive rights, divorce, equal pay, education, maternity leave, breast feeding; and an end to domestic violence, gender stereotypes, discrimination, sexism, objectification, and prostitution. Medha Patkar, Madhu Kishwar, and Brinda Karat are some of the feminist social workers and politicians who advocate women's rights in post-independent India. In literature, Amrita Pritam, Sarojini Sahoo and Kusum Ansal are eminent Indian writers (in Indian languages) who link sexuality with feminism, and advocate women's rights. Rajeshwari Sunder Rajan, Leela Kasturi, Sharmila Rege, Vidyut Bhagat are some of the essayists and social critics who write in favor of feminism in English.

Feminist Theory

Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical, or philosophical, fields. It encompasses work in a variety of disciplines, including approaches to women's roles and life experiences; feminist politics in anthropology and sociology, economics, women's studies; gender studies; feminist literary criticism; and philosophy. Feminist theory aims to understand gender inequality and focuses on gender politics, power relations and sexuality. While providing a critique of social relations, much of feminist theory also focuses on analyzing gender inequalities and on the promotion of women's rights, interests, and issues. Themes explored in feminism include discrimination, stereotyping, objectification (especially sexual objectification), oppression, and patriarchy.[21]

Elaine Showalter describes the development of feminist theory as having a number of phases. The first she calls "feminist critique" - where the feminist reader examines the ideologies behind literary phenomena. The second Showalter calls "Gynocritics" - where the "woman is producer of textual meaning" including "the psychodynamics of female creativity; linguistics and the problem of a female language; the trajectory of the individual or collective female literary career [and] literary history." The last phase she calls "gender theory" - where the "ideological inscription and the literary effects of the sex/gender system" are explored."[22] This model has been criticized by Toril Moi who sees it as an essentialist and deterministic model for female subjectivity. She also criticized it for not taking account of the situation for women outside the west.[23]

Feminism's Many Forms

Several subtypes of feminist ideology have developed over the years; some of the major subtypes are listed as follows:

Liberal feminism

Liberal feminism asserts the equality of men and women through political and legal reform. It is an individualistic form of feminism and feminist theory, which focuses on women’s ability to show and maintain their equality through their own actions and choices. Liberal feminism looks at the personal interactions between men and women as the starting ground from which to introduce gender-equity into society. According to liberal feminists, all women are capable of asserting their ability to achieve equality; therefore it is possible for change to come about without altering the structure of society. Issues important to liberal feminists include reproductive and abortion rights, sexual harassment, voting, education, "equal pay for equal work," affordable childcare, affordable health care, and bringing to light the frequency of sexual and domestic violence against women.[24]

Radical feminism

Radical feminism identifies the capitalist sexist hierarchy as the defining feature of women’s oppression. Radical feminists believe that women can free themselves only when they have done away with what they consider an inherently oppressive and dominating system. Radical feminists feel that male-based authority and power structures are responsible for oppression and inequality, and that as long as the system and its values are in place, society will not be able to reform in any significant way. Radical feminism sees capitalism as a barrier to ending oppression. Most radical feminists see no alternatives other than the total uprooting and reconstruction of society in order to achieve their goals.[7]

Separatist feminism is a form of radical feminism that rejects heterosexual relationships, believing that the sexual disparities between men and women are unresolvable. Separatist feminists generally do not feel that men can make positive contributions to the feminist movement, and that even well-intentioned men replicate the dynamics of patriarchy. Author Marilyn Frye describes separatist feminism as "separation of various sorts or modes from men and from institutions, relationships, roles and activities that are male-defined, male-dominated, and operating for the benefit of males and the maintenance of male privilege—this separation being initiated or maintained, at will, by women."[25]

Both the self-proclaimed sex-positive and the so-called sex-negative forms of present-day feminism can trace their roots to early radical feminism. Ellen Willis's 1981 essay, "Lust Horizons: Is the Women's Movement Pro-Sex?" is the origin of the term, "pro-sex feminism." In it, she argues against feminism making alliances with the political right in opposition to pornography and prostitution, as occurred, for example, during the Meese Commission hearings in the United States.[26]

Another strand of radical feminism is "Anarcha-feminism" (also called anarchist feminism or anarcho-feminism). It combines feminist ideas and anarchist beliefs. Anarcha-feminists view patriarchy as a manifestation of hierarchy, believing that the struggle against patriarchy is an essential part of class struggle and the anarchist struggle against the state.[27] Anarcha-feminists like Susan Brown see the anarchist struggle as a necessary component of feminist struggle, in Brown's words "anarchism is a political philosophy that opposes all relationships of power, it is inherently feminist."[28]Wendy McElroy has defined a position (she describes it as "ifeminism" or "individualist feminism") that combines feminism with anarcho-capitalism or libertarianism, arguing that a pro-capitalist, anti-state position is compatible with an emphasis on equal rights and empowerment for women.[29]

Individualist feminism

Individualist feminists define "Individualist feminism" in opposition to political or gender feminism.[30] It is closely linked to the libertarian ideas of individuality and personal responsibility of both women and men. Critics believe that individual feminism reinforces patriarchal systems because it does not view the rights or political interests of men and women as being in conflict, nor does it rest upon class/gender analysis.[31] Individualist feminists attempt to change legal systems in order to eliminate class privileges, including gender privileges, and to ensure that individuals have an equal right, an equal claim under law to their own persons and property. Individualist feminism encourages women to take full responsibility over their own lives. It also opposes any government interference into the choices adults make with their own bodies, contending that such interference creates a coercive hierarchy.[30]

Black feminism

Black feminism argues that sexism and racism are inextricable from one another.[32] Forms of feminism that strive to overcome sexism and class oppression but ignore race can discriminate against many people, including women, through racial bias. Black feminists argue that the liberation of black women entails freedom for all people, since it would require the end of racism, sexism, and class oppression.[33]

One of the theories that evolved out of this movement was Alice Walker's Womanism which emerged after the early feminist movements that were led specifically by white women who advocated social changes such as woman’s suffrage. These movements were largely a white middle-class movements and ignored oppression based on racism and classism. Alice Walker and other Womanists pointed out that black women experienced a different and more intense kind of oppression from that of white women.[34]

Angela Davis was one of the first people who formed an argument centered on intersection of race, gender and class in her book, Women, Race, and Class.[35] Kimberle Crenshaw, prominent feminist law theorist, gave the idea a name while discussing Identity Politics.[36]

Socialist and Marxist feminisms

Socialist feminism connects the oppression of women to Marxist ideas about exploitation, oppression and labor. Socialist feminists see women as being held down as a result of their unequal standing in both the workplace and the domestic sphere. Prostitution, domestic work, childcare, and marriage are all seen as ways in which women are exploited by a patriarchal system which devalues women and the substantial work that they do. Socialist feminists focus their energies on broad change that affects society as a whole, and not just on an individual basis. They see the need to work alongside not just men, but all other groups, as they see the oppression of women as a part of a larger pattern that affects everyone involved in the capitalist system.[37]

Karl Marx taught that when class oppression was overcome, gender oppression would vanish as well. According to socialist feminists, this view of gender oppression as a sub-class of class oppression is naive, and much of the work of socialist feminists has gone towards separating gender phenomena from class phenomena. Some contributors to socialist feminism have criticized traditional Marxist ideas for being largely silent on gender oppression except to subsume it underneath broader class oppression.[38] Other socialist feminists, notably two long-lived American organizations Radical Women and the Freedom Socialist Party, point to the classic Marxist writings of Friedrich Engels[39] and August Bebel[40] as a powerful explanation of the link between gender oppression and class exploitation.

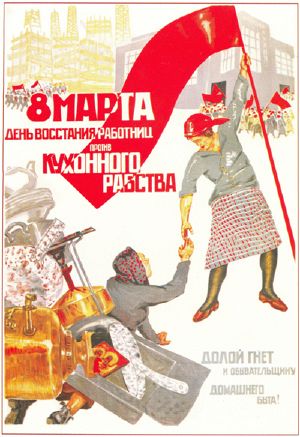

In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century both Clara Zetkin and Eleanor Marx were against the demonization of men and supported a proletarian revolution that would overcome as many male-female inequalities as possible.[41]

Post-structural and postmodern feminism

Post-structural feminists, also referred to as French feminists, use the insights of various epistemological movements, including psychoanalysis, linguistics, political theory (Marxist and neo-Marxist theory), race theory, literary theory, and other intellectual currents to explore and define feminist concerns.[42] Many post-structural feminists maintain that difference is one of the most powerful tools that females possess in their struggle with patriarchal domination, and that to equate feminist movement only with gender equality is to deny women a plethora of options, as "equality" is still defined within a masculine or patriarchal perspective.[43]

Postmodern feminism is an approach to feminist theory that incorporates postmodern and post-structuralist theory. The largest departure from other branches of feminism, is the argument that sex as well as gender is constructed through language.[44] The most notable proponent of this argument is Judith Butler, in her 1990 book, Gender Trouble, which draws on, and criticizes the work of Simone de Beauvoir, Michel Foucault and Jacques Lacan. Butler criticizes the distinction drawn by previous feminisms between (biological) sex and socially constructed gender. She says that this does not allow for a sufficient criticism of essentialism (the concept that certain qualities or characteristics are essential to the definition of gender). For Butler "women" and "woman" are fraught categories, complicated by class, ethnicity, sexuality, and other facets of identity. She suggests that gender is performative. This argument leads to the conclusion that there is no single cause for women's subordination, and no single approach towards dealing with the issue.[44]

In A Cyborg Manifesto Donna Haraway criticizes traditional notions of feminism, particularly its emphasis on identity, rather than affinity. She uses the metaphor of a cyborg (an organism that is a self-regulating integration of artificial and natural systems) in order to construct a postmodern feminism that moves beyond dualisms and the limitations of traditional gender, feminism, and politics.[45] Haraway's cyborg is an attempt to break away from Oedipal narratives and Christian origins doctrines like Genesis: "The cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family, this time without the oedipal project. The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust."[45]

Other postmodern feminist works emphasizes stereotypical female roles, only to portray them as parodies of the original beliefs. The history of feminism is not important to them, their only concern is what is going to be done about it. In fact, the history of feminism is dismissed and used to depict better how ridiculous the past beliefs were. Modern feminist theory has been extensively criticized as being predominantly, though not exclusively, associated with western middle class academia. Mainstream feminism has been criticized as being too narrowly focused, and inattentive to related issues of race and class.[46]

Postcolonial and third-world feminism

Since the 1980s, standpoint feminists have argued that the feminist movement should address global issues (such as rape, incest, and prostitution) and culturally specific issues (such as female genital mutilation in some parts of Africa and the Middle East and glass ceiling practices that impede women's advancement in developed economies) in order to understand how gender inequality interacts with racism, colonialism, and classism in a "matrix of domination."[47] Postcolonial and third world feminists argue that some cultural and class issues must be understood in the context of other political and social needs which may take precedence for women in developing and third world countries.

Postcolonial feminism emerged from the gendered history of colonialism. Colonial powers often imposed Western norms on the regions they colonized. In the 1940s and 1950s, after the formation of the United Nations, former colonies were monitored by the West for what was considered "social progress." The status of women in the developing world has been monitored and evaluated by organizations such as the United Nations, according to essentially Western standards. Traditional practices and roles taken up by women, sometimes seen as distasteful by Western standards, could be considered a form of rebellion against the gender roles imposed by colonial powers.[48] Postcolonial feminists today struggle to fight gender oppression within their own cultural models of society, rather than those imposed by the Western colonizers.[49]

Postcolonial feminists argue that racial, class, and ethnic oppressions relating to the colonial experience have marginalized women in postcolonial societies. They challenge the assumption that gender oppression is the primary force of patriarchy. Postcolonial feminists object to portrayals of women of non-Western societies as passive and voiceless victims, as opposed to the portrayal of Western women as modern, educated and empowered.[50]

Postcolonial feminism is critical of Western forms of feminism, notably radical feminism and liberal feminism and their universalization of female experience. Postcolonial feminists argue that, in cultures impacted by colonialism, the glorification of a pre-colonial culture, in which power was stratified along lines of gender, could include the acceptance of, or refusal to deal with, inherent issues of gender inequality. Postcolonial feminists can be described as feminists who have reacted against both universalizing tendencies in Western feminist thought and a lack of attention to gender issues in mainstream postcolonial thought[50]

Third-world feminism has been described as a group of feminist theories developed by feminists who acquired their views and took part in feminist politics in so-called third world countries[51] Although women from the third world have been engaged in the feminist movement, Chandra Talpade Mohanty criticizes Western feminism on the grounds that it is ethnocentric and does not take into account the unique experiences of women from third world countries or the existence of feminisms indigenous to third world countries. According to her, women in the third world feel that Western feminism bases its understanding of women on its "internal racism, classism and homophobia."[52] This discourse is strongly related to African feminism and postcolonial feminism. Its development is also associated with concepts such as black feminism, womanism,[13] "motherism,"[53] "Stiwanism,"[54] "negofeminism," chicana feminism, and "femalism."

Ecofeminism

Ecofeminism links ecology with feminism. Ecofeminists see the domination of women as stemming from the same ideologies that bring about the domination of the environment. Patriarchal systems, where men own and control the land, are seen as responsible for both the oppression of women and destruction of the natural environment. Since the men in power control the land, they are able to exploit it for their own profit and success, in the same sense that women are exploited by men in power for their own profit, success, and pleasure. As a way of repairing social and ecological injustices, ecofeminists feel that women must work towards creating a healthy environment and ending the destruction of the lands that most women rely on to provide for their families.[55]

Ecofeminism argues that there is a connection between women and nature that comes from their shared history of oppression by a patriarchal western society. Vandana Shiva explains how women's special connection to the environment through their daily interactions with it have been ignored. She says that "women in subsistence economies, producing and reproducing wealth in partnership with nature, have been experts in their own right of holistic and ecological knowledge of nature’s processes. But these alternative modes of knowing, which are oriented to the social benefits and sustenance needs are not recognized by the [capitalist] reductionist paradigm, because it fails to perceive the interconnectedness of nature, or the connection of women’s lives, work and knowledge with the creation of wealth.”[56] Ecofeminists also criticize Western lifestyle choices, such as consuming food that has traveled thousands of miles and playing sports (such as golf and bobsledding) which inherently require ecological destruction.

Feminist and social ecologist Janet Biehl has criticized ecofeminism for focusing too much on a mystical connection between women and nature, and not enough on the actual conditions of women.[57]

Post-feminism

The term 'post-feminism' comprises a wide range of theories, some of which argue that feminism is no longer relevant to today's society.[58] One of the earliest uses of the term was in Susan Bolotin's 1982 article "Voices of the Post-Feminist Generation," published in New York Times Magazine. This article was based on a number of interviews with women who largely agreed with the goals of feminism, but did not identify themselves as feminists.[59] Post-feminism takes a critical approach to previous feminist discourses, including challenges to second-wave ideas.[20]

Sarah Gamble argues that feminists such as Naomi Wolf, Katie Roiphe, Natasha Walter and Rene Denfeld are labeled as 'anti-feminists,' whereas they define themselves as feminists who have shifted from second-wave ideas towards an "individualistic liberal agenda".[60] Denfeld has distanced herself from feminists who see pornography and heterosexuality as oppressive and also criticized what she sees as, the second-wave's "reckless" use of the term patriarchy.[61] Gamble points out that post-feminists like Denfeld are criticized as "pawns of a conservative 'backlash' against feminism."[60]

Issues in Defining Feminism

One of the difficulties in defining and circumscribing a complex and heterogeneous concept such as feminism is the extent to which women have rejected the term from a variety of semantic and political standpoints. Many women engaged in activities intimately grounded in feminism have not considered themselves feminists. It is assumed that only women can be feminists. However, feminism is not grounded in a person's gender, but in their commitment to rejecting and refuting sexist oppression politically, socially, privately, linguistically, and otherwise. Defining feminism in this way reflects the contemporary reality that both men and women openly support feminism, and also openly adhere to sexist ideals.[62]

Politically, use of the term "feminism" has been rejected both because of fears of labeling, and because of its innate ability to attract broad misogyny.[63]Virginia Woolf was one of the more prominent women to reject the term early in its history in 1938,[64] although she is regarded as an icon of feminism.[65] Betty Friedan revisited this concern in 1981 in The Second Stage.[66]

Ann Taylor offered the following definition of a feminist:

Any person who recognizes "the validity of women's own interpretation of their lived experiences and needs," protests against the institutionalized injustice perpetrated by men as a group against women as a group, and advocates the elimination of that injustice by challenging the various structures of authority or power that legitimate male prerogatives in a given society.[67]

Another way of expressing this concept is that a primary goal of feminism is to correct androcentric bias.[68]

However, one of feminism's unique characteristics is its persistent defiance of being constrained by definition:

The multiple and contrary readings of the philosophical canon by feminists reflects the contested nature of the “us” of contemporary feminism. The fact that feminist interpretations of canonical figures is diverse reflects, and is a part of, on-going debates within feminism over its identity and self-image. Disagreements among feminist historians of philosophy over the value of canonical philosophers, and the appropriate categories to use to interpret them, are, in the final analysis, the result of debate within feminist philosophy over what feminism is, and what is theoretical commitments should be, and what its core values are.[69]

Some contemporary women and men have distanced themselves from the term "femin"ism in favor of more inclusive terminology such as "equal rights activist/advocate," "equalist" or similar non-gendered phrasings.

Feminism and Society

The feminist movement has effected a number of changes in Western society, including women's suffrage; the right to initiate divorce proceedings and "no fault" divorce; access to university education; and the right of women to make individual decisions regarding pregnancy (including access to contraceptives and abortion).[70]

Language

Gender-neutral language is the usage of terminology which is aimed at minimizing assumptions regarding the biological sex of human referents. Gender-neutral language is advocated both by those who aim to clarify the inclusion of both sexes or genders (gender-inclusive language); and by those who propose that gender, as a category, is rarely worth marking in language (gender-neutral language). Gender-neutral language is sometimes described as non-sexist language by advocates, and politically-correct language by opponents.

Heterosexual relationships

The increased entry of women into the workplace which began during the Industrial Revolution and increased rapidly during the twentieth and century has affected gender roles and the division of labor within households. The sociologist, Arlie Russell Hochschild, presents evidence in her books, The Second Shift and The Time Bind, that in two-career couples, men and women on the average spend about equal amounts of time working, but women still spend more time on housework.[71][72]

Feminist criticisms of men's contributions to child care and domestic labor in the Western middle class are typically centered around the idea that it is unfair for women to be expected to perform more than half of a household's domestic work and child care when both members of the relationship also work outside the home. Feminism has affected women’s choices to bear a child, both in and out of wedlock, by making the choice less dependent on the financial and social support of a male partner.[73]

Religion

Feminist theology is a movement that reconsiders the traditions, practices, scriptures, and theologies of their religion from a feminist perspective. Some of the goals of feminist theology include increasing the role of women among the clergy and religious authorities, reinterpreting male-dominated imagery and language about God, determining women's place in relation to career and motherhood, and studying images of women in the religion's sacred texts.[74]

Christian feminism

Christian feminism is a branch of feminist theology which seeks to interpret and understand Christianity in terms of the equality of women and men morally, socially, and in leadership. Because this equality has been historically ignored, Christian feminists believe their contributions are necessary for a complete understanding of Christianity. While there is no standard set of beliefs among Christian feminists, most agree that God does not discriminate on the basis of biologically-determined characteristics such as gender. Their major issues are the ordination of women, male dominance in Christian marriage, and claims of moral deficiency and inferiority of the abilities of women compared to men. They also are concerned with issues such as the balance of parenting between mothers and fathers and the overall treatment of women in the church.[75]

Jewish feminism

Jewish feminism is a movement that seeks to improve the religious, legal, and social status of women within Judaism and to open up new opportunities for religious experience and leadership for Jewish women. Feminist movements, with varying approaches and successes, have opened up within all major branches of Judaism. In its modern form, the movement can be traced to the early 1970s in the United States. According to Judith Plaskow, who has focused on feminism in Reform Judaism, the main issues for early Jewish feminists in these movements were the exclusion from the all-male prayer group or minyan, the exemption from positive time-bound mitzvot (coming of age ceremony), and women's inability to function as witnesses and to initiate divorce.[76]

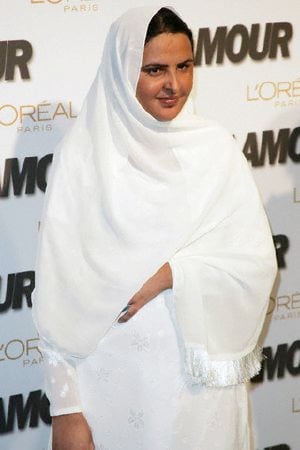

Islamic feminism

Islamic feminism is concerned with the role of women in Islam. It aims for the full equality of all Muslims, regardless of gender, in public and private life. Islamic feminists advocate women's rights, gender equality, and social justice grounded in an Islamic framework. Although rooted in Islam, the movement's pioneers have also utilized secular and Western feminist discourses and recognize the role of Islamic feminism as part of an integrated global feminist movement. Advocates of the movement seek to highlight the deeply rooted teachings of equality in the Qur'an and encourage a questioning of the patriarchal interpretation of Islamic teaching through the Qur'an (holy book), hadith (sayings of Muhammed) and sharia (law) towards the creation of a more equal and just society.

Scientific Research into Feminist Issues

Some natural and social scientists have considered feminist ideas and feminist forms of scholarship using scientific methods.

One core scientific controversy involves the issue of the social construction versus the biological formation of gender- or sex-associated identities. Modern feminist science examines the view that most, if not all, differences between the sexes are based on socially constructed gender identities rather than on biological sex differences. Anne Fausto-Sterling's book Myths of Gender explores the assumptions, embodied in scientific research, that purport to support a biologically essentialist view of gender.[77] In The Female Brain, Louann Brizendine argues that brain differences between the sexes are a biological reality, with significant implications for sex-specific functional differences.[78] Steven Rhoads' book Taking Sex Differences Seriously, illustrates sex-dependent differences in a variety of areas.[79]

Carol Tavris, in The Mismeasure of Woman (the title is a play on Stephen Jay Gould's The Mismeasure of Man), uses psychology, sociology, and analysis in a critique of theories that use biological reductionism to explain differences between men and women. She argues that such theories, rather being based on an objective analysis of the evidence of innate gender difference, have grown out of an over-arching hypothesis intended to justify inequality and perpetuate stereotypes.[80]

Sarah Kember, drawing from numerous areas such as evolutionary biology, sociobiology, artificial intelligence, and cybernetics, discusses the biologization of technology. She notes how feminists and sociologists have become suspect of evolutionary psychology, particularly inasmuch as sociobiology is subjected to complexity in order to strengthen sexual difference as immutable through pre-existing cultural value judgments about human nature and natural selection. Where feminist theory is criticized for its "false beliefs about human nature," Kember then argues in conclusion that "feminism is in the interesting position of needing to do more biology and evolutionary theory in order not to simply oppose their renewed hegemony, but in order to understand the conditions that make this possible, and to have a say in the construction of new ideas and artefacts."[81]

Other Concepts

Pro-feminism is support of feminism without implying that the supporter is a member of the feminist movement. The term is most often used in reference to men who are actively supportive of feminism and of efforts to bring about gender equality. The activities of pro-feminist men's groups include anti-violence work with boys and young men in schools, offering sexual harassment workshops in workplaces, running community education campaigns, and counseling male perpetrators of violence. Pro-feminist men also are involved in men's health, activism against pornography including anti-pornography legislation, men's studies, the development of gender equity curricula in schools, and many other areas. This work is sometimes in collaboration with feminists and women's services, such as domestic violence and rape crisis centers. Some activists of both genders will not refer to men as "feminists" at all, and will refer to all pro-feminist men as "pro-feminists".[82]

Anti-feminism

Opposition to feminism comes in many forms, either criticizing feminist ideology and practice, or arguing that it should be restrained. In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, antifeminists opposed particular policy proposals for women's rights, such as the right to vote, educational opportunities, property rights, and access to birth control. In the mid and late twentieth century, antifeminists often opposed the abortion-rights movement and, in the United States, the Equal Rights Amendment.

In the early twenty-first century, some antifeminists in the United States see their ideology as a response to one rooted in hostility towards men, holding feminism responsible for several social problems, including lower college entrance rates of young men, gender differences in suicide, and a perceived decline in manliness in American culture.

Feminists such as Camille Paglia, Christina Hoff Sommers, Jean Bethke Elshtain, and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese have been labeled "antifeminists" by other feminists. Patai and Koerge argue that in this way the term "antifeminist" is used to silence academic debate about feminism.[83]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rebecca Walker, "Becoming the Third Wave," in Ms. (January/February, 1992): 39-41

- ↑ Ted Honderich, The Oxford companion to philosophy. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 0198661320), 292.

- ↑ Charlotte Krolokke and Anne Scott Sorensen, Gender Communication Theories and Analyses: From Silence to Performance (Sage, 2005, ISBN 978-0761929178).

- ↑ Melanie Phillips, The Ascent of Woman: A History of the Suffragette Movement (Abacus, 2004, ISBN 9780349116600).

- ↑ Eleanor Flexner, Century of Struggle: The Woman's Rights Movement in the United States. (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 1996. ISBN 9780674106539).

- ↑ Imelda Whelehan, Modern Feminist Thought (Edinburgh University Press, 1995, ISBN 9780748606214).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975 (University of Minnesota Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0816617876).

- ↑ Juliet Mitchell, "Women: The longest revolution," in New Left Review (Nov-Dec 1966): 11-37.

- ↑ Warren Hinckle and Marianne Hinckle, "Women Power." Ramparts (February 22-31, 1968).

- ↑ Jo Freeman, The Politics of Women's Liberation (New York: David McKay, 1975, ISBN 978-0679302766).

- ↑ Margalit Fox, "Betty Friedan, Who Ignited Cause in 'Feminine Mystique,' Dies at 85" The New York Times, February 5, 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ↑ Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: W.W. Norton and Company Inc., 1963, ISBN 978-0393084361).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Rebecca Walker, To Be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism (Anchor, 1995, ISBN 9780385472625).

- ↑ Stacy Gillis, Gillian Howie, and Rebecca Munford, (eds.), Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, ISBN 9780230521742).

- ↑ Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology: Metaethics of Radical Feminism (Women's Press Ltd, 1979, ISBN 9780704338500).

- ↑ Christina Hoff Sommers, Who Stole Feminism? - How women have betrayed women (Simon & Schuster Ltd, 1996, ISBN 9780684801568).

- ↑ Katha Pollitt, Reasonable Creatures: Essays on Women and Feminism (New York: Vintage, 1995, ISBN 9780679762782).

- ↑ Carol Gilligan, In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development (Harvard University Press, 1990, ISBN 9780674445444).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (New York: Vintage Books, 1973).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Elizabeth Wright. Lacan and Postfeminism (Icon books, 2000, ISBN 9781840461829).

- ↑ Nancy J. Chodorow, Feminism and Psychoanalytic Theory (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0300051162).

- ↑ Elaine Showalter, "Toward a Feminist Poetics: Women’s Writing and Writing About Women," in The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature and Theory (Random House, 1988, ISBN 9780394726472).

- ↑ Toril Moi, Sexual/Textual Politics (Routledge, 2002, ISBN 9780415280129).

- ↑ bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0896086135).

- ↑ Marilyn Frye, "Some Reflections on Separatism and Power." In Feminist Social Thought: A Reader, edited by Diana Tietjens Meyers, (New York: Routledge, 1997, ISBN 978-0415915373), 406-414.

- ↑ Ellen Willis, Lust Horizons: The 'Voice' and the women's movement Village Voice, October 18, 2005. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ↑ Lynne Farrow, Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-feminist Reader (AK Press, 2003, ISBN 9781902593401).

- ↑ Susan Brown, "Beyond Feminism: Anarchism and Human Freedom" Anarchist Papers 3. Dimitrios Roussopoulos, (ed.), (Black Rose Books, 1990), 208.

- ↑ Wendy McElroy, XXX: A Woman's Right to Pornography. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Wendy McElroy (ed.), Liberty for Women: Freedom and Feminism in the Twenty-First Century (London: Ivan R. Dee, 2002, ISBN 1566634350).

- ↑ Wendy McElroy, Good Will Toward Men, The Libertarian Enterprise 153, December 24, 2001. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ Patricia Hill Collins, Defining Black Feminist Thought The Feminist eZine. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ A Black Feminist Statement From The Combahee River Collective, April 1977. The Feminist eZine. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens (Mariner Books, 2003, ISBN 978-0156028646).

- ↑ Angela Davis, Women, Race, and Class (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1983, ISBN 978-0394713519).

- ↑ Kimberle Crenshaw, "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Color" Stanford Law Review 43(6) (July, 1991): 1241-1299.

- ↑ Barbara Ehrenreich, "What is Socialist Feminism" WIN Magazine, 1976.

- ↑ Clara Connolly, Lynne Segal, Michele Barrett, Beatrix Campbell, Anne Phillips, Angela Weir, and Elizabeth Wilson, "Feminism and Class Politics: A Round-Table Discussion," in Feminist Review 23 Socialist-Feminism: Out of the Blue (Summer, 1986): 13-30.

- ↑ Friedrich Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (Lawrence & Wishart Ltd, 1972, ISBN 9780853152606).

- ↑ August Bebel, Woman under Socialism (University Press of the Pacific, 2004, ISBN 9781410215642).

- ↑ John Stokes, Eleanor Marx (1855-1898): Life, Work, Contacts, and: Socialist Women: Britain, 1880s to 1920s (Ashgate, 2000, ISBN 9780754601135).

- ↑ Barbara Johnson, The Feminist Difference: Literature, Psychoanalysis, Race and Gender (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0674001916).

- ↑ Luce Irigaray, "When Our Lips Speak Together" in Feminist Theory and the Body: A Reader, ed. by Janet Price and Margrit Shildrick, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0748610891).

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Routledge, 1999, ISBN 9780415924993).

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature] (New York: Routledge, 1991, ISBN 978-0415903875).

- ↑ Mary Joe Frug, "A Postmodern Feminist Legal Manifesto (An Unfinished Draft)," Harvard Law Review 105(5) (March, 1992): 1045-1075.

- ↑ P. Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (New York: Routledge, 2008, ISBN 978-0415964722).

- ↑ Chandra Talpade Mohanty, "Under Western Eyes/" Feminist Review 30 (Autumn, 1988): 61-88.

- ↑ Chilla Bulbeck, Re-orienting Western Feminisms: Women's Diversity in a Postcolonial World (Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 9780521580304).

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 S. Mills, "Postcolonial Feminist Theory," in Stevi Jackson and Jackie Jones (eds.), Contemporary Feminist Theories (NYU Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0814742495), 98-122.

- ↑ Uma Narayan, Dislocating Cultures: Identities, Traditions, and Third-World Feminism (New York: Routledge, 1997, ISBN 978-0415914192).

- ↑ C. Mohanty, "Introduction" in Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism. (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0253206329), 7

- ↑ Catherine Obianuju Acholonu, Motherism: The Afrocentric Alternative to Feminism (Owerri, Nigeria: Afa Publications, 1995, ISBN 978-9783199712).

- ↑ Molara Ogundipe-Leslie, Re-Creating Ourselves: African Women & Critical Transformations (Africa World Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0865434127).

- ↑ Sherilyn MacGregor, Beyond Mothering Earth: Ecological Citizenship (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007, ISBN 0774812028).

- ↑ Vandana Shiva, Staying Alive: Women Ecology and Development (Zed Books Ltd, 1989, ISBN 9780862328238).

- ↑ Janet Biehl, Rethinking Ecofeminist Politics (South End Press, 1991, ISBN 9780896083929).

- ↑ Tania Modleski, Feminism without Women: Culture and Criticism in a “Postfeminist” Age (New York: Routledge, 1991, ISBN 978-0415904179).

- ↑ Ruth Rosen, The World Split Open: How the Modern Women's Movement Changed America (Penguin Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0140097191).

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Sarah Gamble (ed.), The icon Critical Dictionary of Feminism and Postfeminism (Icon books, 1999, ISBN 978-1840460421).

- ↑ Rene Denfeld, The New Victorians: A Young Woman's Challenge to the old Feminist Order (Simon and Schuster, 1995, ISBN 978-0446517522).

- ↑ Margaret Walters, Feminism: A very short introduction (Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 019280510X).

- ↑ Ann Oakley and Juliet Mitchell (eds.), Who's Afraid of Feminism?: Seeing Through the Backlash (New Press, 1997, ISBN 1565843851).

- ↑ Virginia Woolf, Three Guineas (Harvest Books, 2006 (original 1938), ISBN 0156031639).

- ↑ Brenda Silver, Virginia Woolf: Icon (University of Chicago Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0226757469).

- ↑ Betty Friedan, The Second Stage (Harvard University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0674796553).

- ↑ Ann Taylor Allen, Feminism, Social Science, and the Meanings of Modernity: The Debate on the Origin of the Family in Europe: and the United States, 1860–1914 Histor Cooperative. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ Joan Marler, "The Myth of Universal Patriarchy: A Critical Response to Cynthia Eller’s Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory." Feminist Theology 14(2) (2006): 163-187.

- ↑ Feminist History of Philosophy Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, May 20, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ↑ Ellen Messer-Davidow, Disciplining feminism: From social activism to academic discourse (Duke University Press, 2002, ISBN 9780822328437).

- ↑ Arlie Russell Hochschild, The Second Shift (Penguin, 2003, ISBN 978-0142002926)

- ↑ Arlie Russell Hochschild, The Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work (Holt Paperbacks, 2001, ISBN 978-0805066432).

- ↑ Kristin Luker, Dubious Conceptions: The Politics of the Teenage Pregnancy Crisis (Harvard University Press, 1997, ISBN 0674217039).

- ↑ Linda Bundesen, The Feminine Spirit: Recapturing the Heart of Scripture (Jossey Bass Wiley, 2007, ISBN 9780787984953).

- ↑ Pamela Sue Anderson and Beverley Clack (eds.), Feminist Philosophy of Religion: Critical readings (Routledge, 2004, ISBN 978-0415257503).

- ↑ Judith Plaskow, "Jewish Feminist Thought" in Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman (eds.), History of Jewish Philosophy (Routledge, 2003, ISBN 978-0415324694).

- ↑ Anne Fausto-Sterling, Myths of Gender: Biological Theories About Women and Men (Basic Books Inc., 1992, ISBN 0465047920).

- ↑ Louann Brizendine, The Female Brain (Broadway Books, 2006, ISBN 0767920090).

- ↑ Steven E. Rhoads, Taking Sex Differences Seriously (Encounter Books, 2004, ISBN 978-1893554931).

- ↑ Carol Tavris, The Mismeasure of Woman: Why Women Are Not the Better Sex, inferior or Opposite Sex (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992, ISBN 0671662740).

- ↑ Sarah Kember, "Resisting the New Evolutionism," Women: A Cultural Review 12(1) (2001): 1-8.

- ↑ Michael Kimmel and Thomas E. Mosmiller (eds.), Against the Tide: Pro-Feminist Men in the United States, 1776-1990 a Documentary History (Boston: Beacon, 1992, ISBN 9780807067673).

- ↑ Daphne Patai and Noretta Koertge, Professing Feminism: Education and Indoctrination in Women's Studies (Lexington Books, 2003, ISBN 978-0739104552).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Acholonu, Catherine Obianuju. Motherism: The Afrocentric Alternative to Feminism. Owerri, Nigeria: Afa Publications, 1995. ISBN 978-9783199712

- Anderson, Pamela Sue, and Beverley Clack (eds.). Feminist Philosophy of Religion: Critical readings. London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0415257503

- de Beauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex. New York: Vintage Books, 2011. ISBN 978-0307277787

- Bebel, August. Woman under Socialism. University Press of the Pacific, 2004. ISBN 9781410215642

- Biehl, Janet. Rethinking Ecofeminist Politics. South End Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0896083929

- Brizendine, Louann. The Female Brain. Broadway Books, 2006. ISBN 0767920090

- Bulbeck, Chilla. Re-orienting Western Feminisms: Women's Diversity in a Postcolonial World. Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0521580304

- Bundesen, Linda. The Feminine Spirit: Recapturing the Heart of Scripture. Jossey Bass Wiley, 2007. ISBN 978-0787984953

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1999. ISBN 978-0415924993

- Chodorow, Nancy J. Feminism and Psychoanalytic Theory. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0300051162

- Collins, P. Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge, 2008. ISBN 978-0415964722

- Daly, Mary. Gyn/Ecology: Metaethics of Radical Feminism. Women's Press Ltd, 1979. ISBN 978-0704338500

- Davis, Angela. Women, Race, and Class. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1983. ISBN 978-0394713519

- Denfeld, Rene. The New Victorians: A Young Woman's Challenge to the old Feminist Order. Grand Central Publishing, 1995. ISBN 978-0446517522

- Echols, Alice. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975. University of Minnesota Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0816617876

- Engels, Friedrich. The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Lawrence & Wishart Ltd, 1972. ISBN 9780853152606

- Farrow, Lynne. Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-feminist Reader. AK Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1902593401

- Fausto-Sterling, Anne. Myths of Gender: Biological Theories About Women and Men. Basic Books Inc., 1992. ISBN 0465047920

- Flexner, Eleanor. Century of Struggle: The Woman's Rights Movement in the United States. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0674106536

- Frank,Daniel H., and and Oliver Leaman (eds.). History of Jewish Philosophy. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 978-0415324694

- Freeman, Jo. The Politics of Women's Liberation. New York: David McKay, 1975. ISBN 978-0679302766

- Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton and Company Inc., 1963. ISBN 978-0393084361.

- Friedan, Betty. The Second Stage. Harvard University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0674796553

- Gamble, Sarah (ed.). The icon Critical Dictionary of Feminism and Postfeminism. Icon books, 1999. ISBN 978-1840460421

- Gilligan. Carol. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0674445444

- Gillis, Stacy, Gillian Howie, and Rebecca Munford (eds.). Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration. Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. ISBN 978-0230521742

- Haraway, Donna. "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991. ISBN 978-0415903875

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Second Shift. Penguin, 2003. ISBN 978-0142002926

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work. Holt Paperbacks, 2001 (original 1997). ISBN 978-0805066432

- hooks, bell. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0896086135

- Jackson, Stevi, and Jackie Jones (eds.). Contemporary Feminist Theories. NYU Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0814742495

- Johnson, Barbara. The Feminist Difference: Literature, Psychoanalysis, Race and Gender. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0674001916

- Kimmel, Michael, and Thomas E. Mosmiller (eds.). Against the Tide: Pro-Feminist Men in the United States, 1776-1990 a Documentary History. Boston: Beacon, 1992. ISBN 9780807067673

- Krolokke, Charlotte, and Anne Scott Sorensen. Gender Communication Theories and Analyses: From Silence to Performance. Sage, 2005. ISBN 978-0761929178

- Luker, Kristin. Dubious Conceptions: The Politics of the Teenage Pregnancy Crisis. Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 0674217039

- MacGregor, Sherilyn. Beyond Mothering Earth: Ecological Citizenship. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007. ISBN 0774812028

- Messer-Davidow, Ellen. Disciplining feminism: from social activism to academic discourse. Duke University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0822328437

- Modleski, Tania. Feminism without Women: Culture and Criticism in a “Postfeminist” Age. New York: Routledge, 1991. ISBN 978-0415904179

- Mohanty, Chandra Talpade, Ann Russo, and Lourdes Torres (eds.). Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0253206329

- Moi, Toril. Sexual/Textual Politics. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-0415280129

- Meyers, Diana Tietjens (ed.). Feminist Social Thought: A Reader. New York: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 978-0415915373

- Narayan, Uma. Dislocating Cultures: Identities, Traditions, and Third-World Feminism. New York: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 978-0415914192

- Oakley, Ann, and Juliet Mitchell (eds.). Who's Afraid of Feminism?: Seeing Through the Backlash. New Press, 1997. ISBN 1565843851

- Ogundipe-Leslie, Molara. Re-Creating Ourselves: African Women & Critical Transformations. Africa World Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0865434127

- Patai, Daphne, and Noretta Koertge. Professing Feminism: Education and Indoctrination in Women's Studies. Lexington Books, 2003. ISBN 978-0739104552

- Phillips, Melanie. The Ascent of Woman: A History of the Suffragette Movement. Little, Brown Book Group, 2004. ISBN 978-0349116600

- Pollitt, Katha. Reasonable Creatures: Essays on Women and Feminism. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1995. ISBN 978-0679762782

- Price, Janet, and Margrit Shildrick (eds.). Feminist Theory and the Body: A Reader. Edinburgh University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0748610891

- Rhoads, Steven E. Taking Sex Differences Seriously. Encounter Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1893554931

- Rosen, Ruth. The World Split Open: How the Modern Women's Movement Changed America. Penguin Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0140097191

- Shiva, Vandana. Staying Alive: Women Ecology and Development. Zed Books Ltd, 1989. ISBN 978-0862328238

- Showalter, Elaine (ed.). The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature and Theory. New York: Random House, 1988. ISBN 978-0394726472

- Silver, Brenda. Virginia Woolf: Icon. University of Chicago Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0226757469

- Sommers, Christina Hoff. Who Stole Feminism? - How women have betrayed women. New York: Simon & Schuster Ltd, 1996. ISBN 978-0684801568

- Stokes, John. Eleanor Marx (1855-1898): Life, Work, Contacts, and: Socialist Women: Britain, 1880s to 1920s. Ashgate, 2000. ISBN 9780754601135

- Tavris, Carol. The Mismeasure of Woman: Why Women Are Not the Better Sex, inferior or Opposite Sex. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. ISBN 0671662740

- Walker, Alice. In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens. Mariner Books, 2003. ISBN 978-0156028646

- Walker, Rebecca. To Be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism. Anchor, 1995. ISBN 978-0385472623

- Walters, Margaret. Feminism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 019280510X

- Whelehan, Imelda. Modern Feminist Thought. Edinburgh University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0748606214

- Woolf, Virginia. Three Guineas. Harvest Books, 2006 (original 1938). ISBN 0156031639

- Wright, Elizabeth. Lacan and Postfeminism. Icon books, 2000. ISBN 978-1840461829

External links

All links retrieved March 26, 2024.

- Feminism entries Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Feminist eZine

- Radical Women

- Religious conservatism: Feminist theology as a means of combating injustice towards women in Muslim communities/culture Riffat Hassan

- The Feminist Revolution Jewish Women's Archive

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Feminism history

- Cyborg history

- Essentialism history

- History_of_feminism history

- French_feminism history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.